Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP) in New Zealand; a Retrospective Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

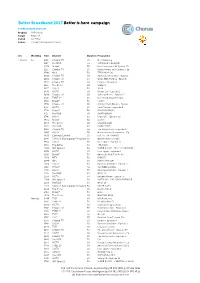

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

WHERE ARE the EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020 Summary of the net daily reach of the main TV broadcasters on air and online in 2020 Daily reach 2020 – net reach of TV broadcasters. All New Zealanders 15+ • Net daily reach of TVNZ: 56% – Includes TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, DUKE, TVNZ OnDemand • Net daily reach of Mediaworks : 25% – Includes Three, 3NOW • Net daily reach of SKY TV: 22% – Includes all SKY channels and SKY Ondemand Glasshouse Consulting June 20 2 The difference in the time each generation dedicate to different media each day is vast. 60+ year olds spend an average of nearly four hours watching TV and nearly 2½ hours listening to the radio each day. Conversely 15-39 year olds spend nearly 2½ hours watching SVOD, nearly two hours a day watching online video or listening to streamed music and nearly 1½ hours online gaming. Time spent consuming media 2020 – average minutes per day. Three generations of New Zealanders Q: Between (TIME PERIOD) about how long did you do (activity) for? 61 TV Total 143 229 110 Online Video 56 21 46 Radio 70 145 139 SVOD Total 99 32 120 Music Stream 46 12 84 Online Gaming 46 31 30 NZ On Demand 37 15-39s 26 15 40-59s Music 14 11 60+ year olds 10 Online NZ Radio 27 11 16 Note: in this chart average total minutes are based on a ll New Zealanders Podcast 6 and includes those who did not do each activity (i.e. zero minutes). 3 Media are ranked in order of daily reach among all New Zealanders. -

Download 2018 Media Guide

14–18 May 2018 Be heard A media guide for schools TOGETHER WE CAN STOP BULLYING AT OUR SCHOOL www.bullyingfree.nz Contents Why use the media? ................................................................................................... 3 Developing key messages .......................................................................................... 4 News outlets ............................................................................................................... 6 Being in the news ...................................................................................................... 9 Writing a media release ........................................................................................... 10 Tips on media interviews ......................................................................................... 12 Involving students in media activity ........................................................................... 13 Responding to media following an incident .............................................................. 14 Who we are Bullying-Free NZ Week is coordinated by the Bullying Prevention Advisory Group (BPAG). BPAG is an interagency group of 17 organisations, with representatives from the education, health, justice and social sectors, as well as internet safety and human rights advocacy groups. BPAG members share the strongly held view that bullying behaviour of any kind is unacceptable and are committed to ensuring combined action is taken to reduce bullying in New Zealand Schools. Find out more -

Critical Literacy in Support of Critical-Citizenship Education in Social Studies

TEACHING AND LEARNING Critical literacy in support of critical-citizenship education in social studies JANE ABBISS KEY POINTS • Critical-literacy approaches support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. • Developing learner criticality involves analysis of texts, including exploration of author viewpoints, assumptions made, matters of inclusion, and learner responses to social issues and how they are represented in texts. • Taking a critical literacy approach to support critical citizenship involves re-thinking how students in social studies engage with media sources. • Critical literacy aids informed decision-making on social issues. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0054 set 3, 2016 29 TEACHING AND LEARNING How might social-studies teachers enact critical forms of citizenship education in classrooms and what pedagogies support this? This question is explored in relation to literature about critical citizenship and critical literacy. Also, possibilities for practice are considered and two approaches for critical literacy in social studies are presented: a) using critical questions to engage with texts; and b) focusing on media literacy in relation to current events. It is argued that critical literacy offers a collection of approaches that support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. Introduction Methodologically, this article presents a literature- based, small-scale practitioner inquiry relating to The aim of this article is twofold: first, to briefly challenges in supporting citizenship teaching and explore some contested views of citizenship education learning in social studies. At its core is a commitment and to consider the aims and foundations of critical to informing practice (Cochrane-Smith & Donnell, literacy as a collection of pedagogical approaches 2006; Smith & Helfenbein, 2009). -

WHERE ARE the AUDIENCES? August 2021 Introduction

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? August 2021 Introduction • New Zealand On Air (NZ On Air) supports and funds public media content for New Zealand audiences, focussing on authentic NZ stories and songs that reflect New Zealand’s cultural identity and help build social cohesion, inclusion and connection. • It is therefore essential NZ On Air has an accurate understanding of the evolving media behaviour of NZ audiences. • The Where Are The Audiences? study delivers an objective measure of NZ audience behaviour at a time when continuous single source audience measurement is still in development. • This document presents the findings of the 2021 study. This is the fifth wave of the study since the benchmark in 2014 and provides not only a snapshot of current audience behaviour but also how behaviour is evolving over time. • NZ On Air aims to hold a mirror up to New Zealand and its people. The 2021 Where Are The Audiences? study will contribute to this goal by: – Informing NZ On Air’s content and platform strategy as well as the assessment of specific content proposals – Positioning NZ On Air as a knowledge leader with stakeholders. – Maintaining NZ On Air’s platform neutral approach to funding and support, and ensuring decisions are based on objective, single source, multi-media audience information. Glasshouse Consulting July 21 2 Potential impact of Covid 19 on the 2020 study • The Where Are The Audiences? study has always been conducted in April and May to ensure results are not influenced by seasonal audience patterns. • However in 2020 the study was delayed to May-June due to levels 3 and 4 Covid 19 lockdown prior to this period. -

Fast Facts NZ TV Viewing TAM H2 2020

FAST FACTS NZ Linear TV Viewing - H2 2020 Published February 2021 TV reaches 3.7 million New Zealanders (84%) every month Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Linear TV, Total TV, All People 5+, Average Cumulative Reach, July – December 2020 TV reaches 3.2 million New Zealanders (73%) every week Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Linear TV, Total TV, All People 5+, Average Cumulative Reach, 28 June 2020 – 2 January 2021 TV reaches 2.3 million New Zealanders (53%) every day Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Linear TV, Total TV, All People 5+, Average Cumulative Reach, July – December 2020 96% of New Zealand homes have a television Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Quarter 4 2019 – Quarter 3 2020 New Zealanders spend over 2 hours per day watching TV Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Linear TV, Total TV, All People 5+, July – December 2020 90% of TV is watched live Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement – Linear TV, Total TV, All People 5+, 1 July – 31 December 2020 FAST FACTS NZ Linear TV Viewing - H2 2020 Detailed Charts HOW MANY NEW ZEALANDERS WATCH LINEAR TV? HOW MANY NEW ZEALANDERS WATCH LINEAR TV? 2.3 million New Zealanders in a day 53% of the population 3.2 million New Zealanders in a week 73% of the population 3.7 million New Zealanders in a month 84% of the population Source: Nielsen Television Audience Measurement (Base: All People 5+, Consolidated, July – December 2020, All Day, Average Cumulative Reach (daily/weekly/monthly) HOW MANY PEOPLE DOES -

Roy Morgan Poll Most Accurate on NZ Election

Article No. 8549 Available on www.roymorgan.com Link to Roy Morgan Profiles Tuesday, 20 October 2020 Roy Morgan Poll most accurate on NZ Election – predicting a ‘crushing’ Labour majority for PM Jacinda Ardern The most accurate poll of the weekend’s New Zealand Election was the final Roy Morgan New Zealand Poll which predicted a ‘crushing’ victory for Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and a governing majority for the Labour Party. The official results show the Labour Party with 49.1% of the Party Vote finishing well ahead of National on 26.8%, Act NZ on 8%, the Greens on 7.6% and NZ First on only 2.7%. The final Roy Morgan New Zealand Poll released two days before last Saturday’s election showed the Labour Party with a Parliamentary majority winning lead on 47.5% - closer than the final polls for both 1 News Colmar Brunton (46%) and Newshub-Reid Research (45.8%). Roy Morgan predicted National support of 28.5% which was significantly closer to National’s election result of 26.8% than either Newshub-Reid Research (31%) or 1 News Colmar Brunton (31.1%). All three polls under-estimated the extent of Labour’s support and over-estimated support for National but the average error for the two major parties was only 1.65% for Roy Morgan compared to 3.65% for 1 News Colmar Brunton and 3.8% for Newshub-Reid Research. Roy Morgan was also closest when considering the results of smaller parties such as Act NZ and the Greens and minor parties such as the Maori Party and The Opportunities Party (TOP). -

Download the Brochure

NEW ZEALAND Share Our Vision Shape Your Future www.dlapiper.com/nzgrads SHAPE OUR VISION SHAPE YOUR FUTURE DLA Piper New Zealand’s flagship office in Commercial Bay, Auckland. 2 WWW.DLAPIPER.COM/NZGRADS Contents Introduction to DLA Piper ................................................4 What makes us different ..................................................6 Values, awards and vital statistics ..................................8 Our practice groups ....................................................... 10 Responsible business ..................................................... 12 Why DLA Piper? ............................................................... 14 An interview with Sara Battersby ................................. 15 What we look for ............................................................. 16 Opportunities ................................................................... 17 Your development ........................................................... 18 Law clerk application process and timeline .............. 19 3 SHAPE OUR VISION SHAPE YOUR FUTURE If you want to become a global lawyer you’ve come to the right place DLA Piper is a global business law firm located in more than 40 countries throughout the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia Pacific, positioning us to help clients with their legal needs around the world. We strive to be the leading global business law firm by delivering quality and value to our clients and contributing to the communities we operate in. DLA Piper is a firm that’s challenging -

Trust in News in New Zealand 2021

Trust in news in New Zealand 2021 ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr Merja Myllylahti [email protected] Dr Greg Treadwell [email protected] Auckland University of Technology DATE: April 29, 2021 This snapshot report is published by AUT’s research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD). _______________________________________________________________________ About this snapshot report This is the second JMAD report from the centre’s ongoing research project into the level of trust New Zealanders have in the news. It is produced in collaboration with the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. With permission from the institute’s researchers, we have used the same survey questions and comparable sampling method they use in their annual Digital News Report to measure public trust in news (http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/). This allows international comparisons between levels of trust in Aotearoa New Zealand and 40 countries covered by the Reuters project. In addition to the 2020 survey questions, this year’s survey includes two questions about trust in Covid-19 reporting. As in 2020, survey data for the 2021 report was collected by New Zealand online market research company Horizon Research Ltd. The production of this report was funded by the Auckland University of Technology (AUT), and it has ethics approval from the AUT Ethics Committee (AUTEC). Availability: The report can be freely accessed here. Recommended citation: Myllylahti, M. & Treadwell, G. (2021). Trust in news in New Zealand. AUT research centre for Journalism, Media and Democracy (JMAD). Available: https://www.aut.ac.nz/study/study- options/communication-studies/research/journalism,-media-and-democracy-research-centre/projects This paper is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International: When reproducing any part of this report – including tables and graphs – full attribution must be given to the report authors. -

CESCR, NZ LOIPR, Peace Movement Aotearoa, February 2016

Peace Movement Aotearoa PO Box 9314, Wellington 6141, Aotearoa New Zealand. Tel +64 4 382 8129 Email [email protected] Web site www.converge.org.nz/pma ______________________________________________________________________________ NGO information for the 57th session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, February 2016 List of Issues Prior to Reporting: New Zealand Overview 1. This preliminary report provides an outline of some issues of concern with regard to the state party's compliance with the provisions of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, the Covenant). Its purpose is to assist the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee) with its preparation of the List of Issues Prior to Reporting (LOIPR) in advance of New Zealand's Fourth Periodic Report (the Periodic Report). 2. There are five main sections below: A. Information on Peace Movement Aotearoa B. Constitutional and legal framework C. Indigenous Peoples’ Rights (Articles 1, 2 and 15) i) Overview, ii) Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, and iii) Impact of the activities of New Zealand companies on indigenous communities overseas. D. Socio-economic conditions (Articles 2, 3, 7, 9 11, and others) i) Increasing levels of child poverty, ii) Right to an adequate standard of living: social welfare / paid employment, iii) Housing crisis, iv) Allocation of public spending E. The Optional Protocol to the Covenant 3. More detailed information will be provided on these and other issues in parallel reports from Peace Movement Aotearoa and other NGOs following the state party’s submission of the Periodic Report next year. Due to time constraints, we have not covered as many issues in this report as we would have liked to, and we therefore refer the Committee to the Human Rights Foundation’s report which covers a range of concerns that we share. -

Magic Mushroom Microdosing: Sick Kiwis Call for 'Life-Saving' Class-A Drug to Be Legalised

TV NEWS SPORT Podcasts ThreeNow Auckland Listen to Newshub's Watch the latest latest podcasts current affairs shows 17° 9° 29 May 2021 HOME NEW ZEALAND WORLD POLITICS SPORT ENTERTAINMENT TRAVEL LIFESTYLE TECHNOLOGY RURAL MONEY SHOWS BREAKING NEWS Police arrest man for allegedly threatening to kill National's Simeon Brown NEWSHUB NATION Magic mushroom microdosing: Sick Kiwis call for 'life-saving' Class-A drug to be legalised EXCLUSIVE 5 hours ago Conor Whitten " More From Newshub ! " 0:38 / 11:08 # "You wouldn't withhold chemo from someone who has cancer." Credits: Newshub Nation. Everyday Kiwis with devastating illnesses are turning to small doses of Class-A drugs to find relief and are calling for what they call a 'life-saving' treatment to be made legal for medical purposes. In New Zealand, magic mushrooms and their active ingredient psilocybin sit next to heroin at Passion Project - Taranaki mum the top of the list of prohibited drugs, carrying a maximum of life in prison for supply. creates 'no-stress' magical But an underground movement of sick Kiwis using the drugs to 'microdose' - taking tiny parties amounts for medical purposes - are saying psilocybin can work when all other treatments fail. Ad Newshub Nation What's next for drug reform in New Zealand? 00:00 / 21:55 Wairangi/mental distress... We've been there 1737 Peer Support Learn more Kiwis like 43-year old Mum Lori. "I'm openly admitting on national TV I take class A drugs... I'm concerned about the implications, but I also think it's a story that needs telling," she told Newshub Nation.