Media and Communication in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Deal – the Coordinators

Green Deal – The Coordinators David Sassoli S&D ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first European Parliament and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be 1 February 2020 – H1 2024 the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle President of the European Commission Head of Cabinet Secretary General Chairs and Vice-Chairs Political Group Coordinators EPP S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe ENVI Renew Committee on Europe Dan-Ştefan Motreanu César Luena Peter Liese Jytte Guteland Nils Torvalds Silvia Sardone Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator the Environment, Public Health Greens/EFA GUE/NGL Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Food Safety Pacal Canfin Chair Bas Eickhout Anja Hazekamp Bas Eickhout Alexandr Vondra Silvia Modig Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator S&D S&D EPP S&D Renew ID Europe EPP ITRE Patrizia Toia Lina Gálvez Muñoz Christian Ehler Dan Nica Martina Dlabajová Paolo Borchia Committee on Vice-Chair Vice-Chair Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Coordinator Industry, Research Renew ECR Greens/EFA ECR GUE/NGL and Energy Cristian Bușoi Europe Chair Morten Petersen Zdzisław Krasnodębski Ville Niinistö Zdzisław Krasnodębski Marisa Matias Vice-Chair Vice-Chair -

Bucharest Meeting Summary

PC 242 PC 17 E Original: English NATO Parliamentary Assembly SUMMARY of the meeting of the Political Committee Plenary Hall, Chamber of Deputies, The Parliament (Senate and Chamber of Deputies) of Romania Bucharest, Romania Saturday 7 and Sunday 8 October 2017 www.nato-pa.int November 2017 242 PC 17 E ATTENDANCE LIST Committee Chairperson Ojars Eriks KALNINS (Latvia) General Rapporteur Rasa JUKNEVICIENE (Lithuania) Rapporteur, Sub-Committee on Gerald E. CONNOLLY (United States) Transatlantic Relations Rapporteur, Sub-Committee on Julio MIRANDA CALHA (Portugal) NATO Partnerships President of the NATO PA Paolo ALLI (Italy) Secretary General of the NATO PA David HOBBS Member delegations Albania Mimi KODHELI Xhemal QEFALIA Perparim SPAHIU Gent STRAZIMIRI Belgium Peter BUYSROGGE Karolien GROSEMANS Sébastian PIRLOT Damien THIERY Luk VAN BIESEN Karl VANLOUWE Veli YÜKSEL Bulgaria Plamen MANUSHEV Simeon SIMEONOV Canada Raynell ANDREYCHUK Joseph A. DAY Larry MILLER Marc SERRÉ Borys WRZESNEWSKYJ Czech Republic Milan SARAPATKA Denmark Peter Juel JENSEN Estonia Marko MIHKELSON France Philippe FOLLIOT Sonia KRIMI Gilbert ROGER Germany Karin EVERS-MEYER Karl A. LAMERS Anita SCHÄFER Greece Spyridon DANELLIS Christos KARAGIANNIDIS Meropi TZOUFI Hungary Mihaly BALLA Karoly TUZES Italy Antonino BOSCO Andrea MANCIULLI Andrea MARTELLA Roberto MORASSUT Vito VATTUONE i 242 PC 17 E Latvia Aleksandrs KIRSTEINS Lithuania Ausrine ARMONAITE Luxembourg Alexander KRIEPS Netherlands Herman SCHAPER Norway Liv Signe NAVARSETE Poland Waldemar ANDZEL Adam BIELAN Przemyslaw -

En En Joint Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2019-2024 Plenary sitting B9-0236/2021 } B9-0237/2021 } B9-0250/2021 } B9-0251/2021 } B9-0252/2021 } RC1 28.4.2021 JOINT MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION pursuant to Rule 132(2) and (4) of the Rules of Procedure replacing the following motions: B9-0236/2021 (Verts/ALE) B9-0237/2021 (Renew) B9-0250/2021 (S&D) B9-0251/2021 (PPE) B9-0252/2021 (ECR) on Russia, the case of Alexei Navalny, the military build-up on Ukraine’s border and Russian attacks in the Czech Republic (2021/2642(RSP)) Michael Gahler, Željana Zovko, Andrius Kubilius, Sandra Kalniete, Isabel Wiseler-Lima, Andrzej Halicki, Antonio López-Istúriz White, Miriam Lexmann, David Lega, Rasa Juknevičienė, Jerzy Buzek, Riho Terras, Arba Kokalari, Tomáš Zdechovský, Luděk Niedermayer, Vladimír Bilčík, Traian Băsescu, Jiří Pospíšil, Stanislav Polčák, Eugen Tomac, Michaela Šojdrová on behalf of the PPE Group RC\1230259EN.docx PE692.492v01-00 } PE692.493v01-00 } PE692.506v01-00 } PE692.507v01-00 } PE692.508v01-00 } RC1 EN United in diversityEN Marek Belka, Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, Tonino Picula on behalf of the S&D Group Bernard Guetta, Petras Auštrevičius, Dita Charanzová, Olivier Chastel, Vlad Gheorghe, Klemen Grošelj, Moritz Körner, Dragoș Pîslaru, Frédérique Ries, María Soraya Rodríguez Ramos, Michal Šimečka, Nicolae Ştefănuță, Ramona Strugariu, Dragoş Tudorache on behalf of the Renew Group Sergey Lagodinsky on behalf of the Verts/ALE Group Anna Fotyga, Veronika Vrecionová, Ruža Tomašić, Jadwiga Wiśniewska, Witold Jan Waszczykowski, Elżbieta Rafalska, Hermann Tertsch, Charlie -

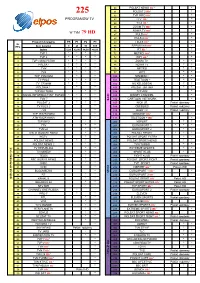

Mini Hd Mały Hd Duży Hd Mega Hd Mega + Hd

MINI HD MAŁY HD DUŻY HD MEGA HD MEGA + HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP1 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVP2 HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD TVN HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD Polsat HD TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV4 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TV6 TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TVN7 HD TTV TTV TTV TTV TTV Polsat 2 Polsat 2 BBC HD BBC HD BBC HD TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP HD TVP HD TVP HD TV Puls TV Puls Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Polsat 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 TVP Polonia TVP Polonia TVP Polonia Tele 5 Tele 5 TV Puls TV Puls TV Puls Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Puls 2 Puls 2 Puls 2 Mango 24 Mango 24 Tele 5 Tele 5 Tele 5 ATM Rozrywka TV ATM Rozrywka Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Polonia 1 Religia TV Edusat HD Mango 24 Mango 24 Mango 24 TV Trwam TVR HD ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka ATM Rozrywka Kościół HD na żywo TVS HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Edusat HD Polsat Sport News Religia TV TVR HD TVR HD TVR HD TVP Info Szczecin TV Trwam TVS HD TVS HD TVS HD TVP Info Gorzów Kościół HD na żywo Religia TV Religia TV Religia TV TVP Info Polsat Sport News TV Trwam TV Trwam TV Trwam TVP Łódź TVN 24 HD Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo Kościół HD na żywo TVP Wrocław Polsat News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News Polsat Sport News TVP Warszawa Polsat Biznes TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVN 24 HD TVP Rzeszów TVN Biznes i Świat Polsat News Polsat News Polsat News TVP Olsztyn TVP Info Szczecin Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes Polsat Biznes TVP Katowice TVP Info Gorzów TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVN Biznes i Świat TVP Gdańsk TVP Info TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin TVP Info Szczecin Stopklatka -

Lista Kanałów

SUPER HD 158 kanały w tym 76 HD KOMFORT HD 143 kanały w tym 65 HD START EXTRA HD 111 kanałów w tym 43 HD 1 TVP1 HD HD 110 France 24 FR HD HD 600 TVP Rozrywka 900 TVP1 2 TVP2 HD HD 111 France 24 EN HD HD 601 ATM Rozrywka 901 TVP2 3 TVP3 Wrocław 113 TwojaTV HD HD 602 RedCarpet TV HD HD 902 TVN 4 TV4 HD HD 200 TVN Fabuła HD HD 607 TVR HD HD 903 TVN7 5 TV6 HD HD 204 Stopklatka.tv HD HD 609 Super Polsat HD HD 904 Puls 6 TVN HD HD 300 TVP Kultura 610 NowaTV HD HD 905 Puls 2 7 TVN7 HD HD 301 TVP Historia 611 ToTV 906 TTV 10 Polsat HD HD 303 FokusTV HD HD 612 WP 907 Tele5 11 Polsat 2 HD HD 310 Polsat Doku HD HD 613 SBN Network 908 Zoom TV 12 Puls HD HD 311 Russia Today DOC HD HD 615 Polsat Games HD HD 909 MetroTV 13 Puls 2 HD HD 400 TVP Sport HD HD 616 Polsat Rodzina HD HD 910 FokusTV 14 TTV HD HD 403 Polsat Sport News HD HD 620 GameToon HD HD 911 NowaTV 15 TVP Polonia 404 Polsat Sport Fight HD HD 800 TVP3 Warszawa 912 TVS 16 Polonia 1 500 4FUN TV 801 TVP3 Gdańsk 913 TVP INFO 17 TVP ABC 501 4FUN GOLDS HITS 802 TVP3 Szczecin 914 Russia Today 18 Tele5 HD HD 502 4FUN DANCE 803 TVP3 Poznań 915 Russia Today DOC 22 Zoom TV HD HD 504 VOX Music TV 804 TVP3 Białystok 916 TVR 23 WP HD HD 505 Polsat Music HD HD 805 TVP3 Olsztyn 917 RedCarpet TV SD 24 MetroTV HD HD 506 Eska TV HD HD 806 TVP3 Bydgoszcz 922 Stopklatka.tv 25 NTL Radomsko 507 Eska TV Extra HD HD 807 TVP3 Gorzów 923 Eska TV 26 Nobox TV 508 Eska Rock TV 808 TVP3 Lublin 924 Eska TV Extra 102 TVP INFO HD HD 509 PowerTV HD HD 809 TVP3 Rzeszów 925 PowerTV 104 Polsat News 2 510 Nuta.TV HD HD 810 TVP3 -

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

Programów Tv

60 POLSAT NEWS HD 1 * 225 61 POLSAT 2 HD 1 * 62 TVP INFO HD 1 * PROGRAMÓW TV 63 TTV HD 1 * 64 TV 4 HD 1 * 65 ZOOM TV HD 1 * 66 NOWA TV HD 1 * W TYM 79 HD 1 67 PULS HD * 68 PULS 2 HD 1 * Program telewizyjny PR P1 P2 P3 69 TELE5 HD 1 * Nr 1 EPG Ilość kanałów 9 21 91 169 70 REPUBLIKA HD * Opłata 5,00 12,00 34,00 46,00 71 RT HD 1 * 1 TVP 1 * * * * 72 METRO HD 1 * 2 TVP 2 * * * * 73 WP1 HD 1 * 3 TVP 3 BIAŁYSTOK * * * * 74 ZOOM TV * * 4 POLSAT * * * * 75 NOWA TV * * 5 TVN * * * * 76 METRO * * 6 TV4 * * * * 77 WP1 * * 7 TVP POLONIA * * 100 MINIMINI + * * 8 TV PULS * * * * 101 TELETOON + * * 9 TV TRWAM * * * * 102 NICKELODEON * * 10 POLONIA 1 * * 103 POLSAT JIM JAM * * 11 TVP KULTURA * * 104 TVP ABC * I 12 KANAŁ INFORMACYJNY ELPOS * * * * K 105 DISNEY CHANNEL * J 13 TVN 7 * * * A 106 CARTOON NETWORK * B 14 POLSAT 2 * * * 107 NICK JR Pakiet domowy 15 TV PULS 2 * 108 CBEEBIES Pakiet rodzinny 16 TV6 * * 109 BABY TV Pakiet rodzinny 17 TVP ROZRYWKA * 110 MINIMINI+ HD 1 * 18 ATM ROZRYWKA * 111 TELETOON + HD 1 * 19 TVP INFO * * 200 NSPORT * * 20 TTV * * 201 EUROSPORT 1 * * * 21 TVN 24 * * 202 EUROSPORT 2 * * 22 TVN 24 BIZNES I ŚWIAT * * 203 POLSAT SPORT * * * 23 HGTV * * 204 POLSAT SPORT EXTRA * * 24 POLSAT NEWS * * * 205 POLSAT SPORT NEWS * * 25 POLSAT NEWS 2 * * 206 TVN TURBO * * E 26 TV REPUBLIKA * * 207 EXTREME SPORTS * * N J 27 TV NAREW * * 208 SPORT KLUB * * Y C 28 TELE5 * * 209 FIGHT KLUB Pakiet sportowy A M 29 BBC WORLD NEWS * * 210 POLSAT SPORT FIGHT Pakiet sportowy R O F 30 CNBC * * 211 TVP SPORT Pakiet sportowy N T I 1 I 31 * R 212 HD CNN -

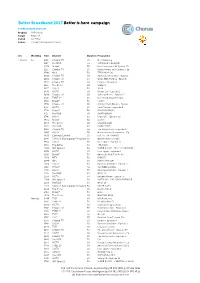

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

Download PDF Version

Next weekend in New Direction 10th Anniversary Dinner p.22 BORDEAUX p.20 ACRE Summer Gala Dinner p.23 Issue #8 | July 2019 A fortnightly Newspaper by the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (ACRE) | theconservative.online THE OFFICIAL OPPOSITION by Jan Zahradil MEP, President of ACRE For the next five years, we aim to serve as the peoples voice, acting as a counter balance between those who want a federal Europe, and those who want to destroy the Union. We will continue to defend the view that Europe works best when it does less, but it does it better. ith the elec- power handed to those who which would have create a in a position to act as the offi- comes as a result of keeping tion now out of want to use it to build a federal more business friendly Europe. cial opposition in the European power as close to the people as Spitzenkandidat the way, and the Europe. A coalition that will That would have put the sin- Parliament. We’ll hold this new possible. And we remain com- JAN ZAHRADIL political groups be led from the left, with any gle market, rather than social coalition to account, and ensure mitted to the view that our nowW establishing themselves, we voting majority dependent on policy, back at the centre of the that they do not use their new strength comes from a willing- Jan Zahradil was ACRE’s can- can now talk with some clarity the support of the Greens and European Union. That would majority to take power away ness to work together on issues didate for the Presidency of the about what the next five years the socialists. -

Radiopodlasie.Pl Wygenerowano W Dniu 2021-09-25 10:49:22

Radiopodlasie.pl Wygenerowano w dniu 2021-09-25 10:49:22 Kto wejdzie do PE? Karol Karski, Krzysztof Jurgiel, Adam Bielan, Zbigniew Kuźmiuk, Elżbieta Kruk i Beata Mazurek(PiS), Tomasz Frankowski, Jarosław Kalinowski i Krzysztof Hetman (KE)- najprawdopodobniej wejdą do Parlamentu Europejskiego. Wszyscy kandydowali w okręgach obejmujących nasz region. Prognozy są oparte na sondażu exit-poll, co oznacza, że nazwiska kandydatów, którzy obejmą mandaty, mogą się jeszcze zmienić. Prawdopodobne nazwiska europarlamentarzystów podaje Informacyjna Agencja Radiowa. Prawo i Sprawiedliwość zdobyło najwięcej, 42,4 procent głosów, w wyborach do Parlamentu Europejskiego - wynika z sondażu exit-poll zrealizowanego przez IPSOS dla telewizji TVP, Polsat i TVN. Drugie miejsce w badaniu prowadzonym dziś przed lokalami wyborczymi zajęła Koalicja Europejska - 39,1 procent. Jeśli wyniki sondażu potwierdzą się, do Parlamentu Europejskiego dostaną się także kandydaci Wiosny - 6,6 procent oraz Konfederacji - 6,1 procent. Pięcioprocentowego prgu nie przekroczyły komitety Kukiz'15 - 4,1 procent oraz Lewica Razem - 1,3 procent. Prognozowana frekwencja wyniosła 43 procent - wynika z sondażu exit-poll. Zgodnie z sondażem, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość wygrało w siedmiu okręgach (warmińsko-mazurskie z podlaskim, Mazowsze, Łódzkie, Lubelskie, Podkarpacie, Małopolska ze Świętokrzyskiem oraz Śląsk). W sześciu okręgach wygrała Koalicja Europejska (Pomorze, kujawsko-pomorskie, Warszawa, Wielkopolska, Dolny Śląsk z Opolszczyzną oraz Lubuskie z Zachodniopomorskim). Z prognozy podziału mandatów wynika, że przy takich wynikach, jakie przyniósł sondaż exit-poll, PiS miałby w Parlamencie Europejskim 24 mandaty, Koalicja Europejska - 22 mandaty, a Wiosna i Konfederacja - po trzy mandaty. Zgodnie z sondażem, w okręgu obejmującym Pomorze dwa mandaty zdobyła Koalicja Europejska (Magdalena Adamowicz oraz najprawdopodobniej Janusz Lewandowski), a jeden Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (najprawdopodobniej Anna Fotyga). -

Lista Kanałów Finetv

SUPER HD 182 kanały w tym 85 HD i 1 w 4K KOMFORT HD 156 kanały w tym 70 HD i 1 w 4K START EXTRA HD 117 kanałów w tym 44 HD i 1 w 4K 1 TVP1 HD HD 300 TVP Kultura HD HD 616 Polsat Rodzina HD HD 916 TVS 2 TVP2 HD HD 301 TVP Historia 620 GameToon HD HD 917 TVP INFO 3 TVP3 Wrocław 303 FokusTV HD HD 800 TVP3 Warszawa 918 Russia Today 4 TV4 HD HD 310 Polsat Doku HD HD 801 TVP3 Gdańsk 919 Russia Today DOC 5 TV6 HD HD 311 Russia Today DOC HD HD 802 TVP3 Szczecin 920 TVR 6 TVN HD HD 317 Jazz HD HD 803 TVP3 Poznań 921 RedCarpet TV SD 7 TVN7 HD HD 400 TVP Sport HD HD 804 TVP3 Białystok 929 Stopklatka.tv 10 Polsat HD HD 403 Polsat Sport News HD HD 805 TVP3 Olsztyn 930 Eska TV 11 Polsat 2 HD HD 404 Polsat Sport Fight HD HD 806 TVP3 Bydgoszcz 931 Eska TV Extra 12 Puls HD HD 500 4FUN TV 807 TVP3 Gorzów 932 PowerTV 13 Puls 2 HD HD 501 4FUN GOLDS HITS 808 TVP3 Lublin 933 Nuta.TV 14 TTV HD HD 502 4FUN DANCE 809 TVP3 Rzeszów 934 StarsTV 15 TVP Polonia 504 VOX Music TV 810 TVP3 Kraków 935 TVP Kultura 16 Polonia 1 505 Polsat Music HD HD 811 TVP3 Opole 936 TVP Sport 17 TVP ABC 506 Eska TV HD HD 812 TVP3 Kielce 937 TBN Poland 18 Tele5 HD HD 507 Eska TV Extra HD HD 813 TVP3 Łódź 938 Mango 24 22 Zoom TV HD HD 508 Eska Rock TV 814 TVP3 Katowice 939 TV Trwam 23 WP HD HD 509 PowerTV HD HD 900 TVP1 999 Radio Przy Kominku HD 24 MetroTV HD HD 510 Nuta.TV HD HD 901 TVP2 25 NTL Radomsko 511 StarsTV HD HD 902 TVN 26 Nobox TV 512 PoloTV 903 TVN7 102 TVP INFO HD HD 513 MusicBox UA 904 Puls 104 Polsat News 2 514 Kino Polska Muzyka 905 Puls 2 105 wPolsce.PL 600 TVP Rozrywka -

A Look at the New European Parliament Page 1 INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMITTEE (INTA)

THE NEW EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT KEY COMMITTEE COMPOSITION 31 JULY 2019 INTRODUCTION After several marathon sessions, the European Council agreed on the line-up for the EU “top jobs” on 2 July 2019. The deal, which notably saw German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen (CDU, EPP) surprisingly designated as the next European Commission (EC) President, meant that the European Parliament (EP) could proceed with the election of its own leadership on 3 July. The EPP and Renew Europe (formerly ALDE) groups, in line with the agreement, did not present candidates for the EP President. As such, the vote pitted the S&D’s David-Maria Sassoli (IT) against two former Spitzenkandidaten – Ska Keller (DE) of the Greens and Jan Zahradil (CZ) of the ACRE/ECR, alongside placeholder candidate Sira Rego (ES) of GUE. Sassoli was elected President for the first half of the 2019 – 2024 mandate, while the EPP (presumably EPP Spitzenkandidat Manfred Weber) would take the reins from January 2022. The vote was largely seen as a formality and a demonstration of the three largest Groups’ capacity to govern. However, Zahradil received almost 100 votes (more than the total votes of the ECR group), and Keller received almost twice as many votes as there are Greens/EFA MEPs. This forced a second round in which Sassoli was narrowly elected with just 11 more than the necessary simple majority. Close to 12% of MEPs did not cast a ballot. MEPs also elected 14 Vice-Presidents (VPs): Mairead McGuinness (EPP, IE), Pedro Silva Pereira (S&D, PT), Rainer Wieland (EPP, DE), Katarina Barley (S&D, DE), Othmar Karas (EPP, AT), Ewa Kopacz (EPP, PL), Klara Dobrev (S&D, HU), Dita Charanzová (RE, CZ), Nicola Beer (RE, DE), Lívia Járóka (EPP, HU) and Heidi Hautala (Greens/EFA, FI) were elected in the first ballot, while Marcel Kolaja (Greens/EFA, CZ), Dimitrios Papadimoulis (GUE/NGL, EL) and Fabio Massimo Castaldo (NI, IT) needed the second round.