Cornering Control: Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Motorized Drift Trike Hayden Pegley

Building a Motorized Drift Trike Hayden Pegley ASR - F Block - 5/17/2017 Abstract: The goal of this project was to create an affordable motorized drift trike using a hand-welded steel frame, the front half of a used mountain bike, and a 6.5 hp, 212 cc Predator gas engine. The back frame of the trike was welded over the course of several weeks, and components including the axle, front wheel, and throttle system were added after the frame’s completion. While the trike is not fully operational, the throttle system is functional and the trike is near completion. Introduction, Motivation, and History During my freshman year, while conducting an experiment in the Whitaker Lab, I stumbled upon a go kart that an ASR student had recently completed. I was fascinated by the idea of making an operational automobile during high school. I promised myself then and there that I would take ASR and make a go kart of my own for my second semester project. However, as I began the initial research stages for my project and read previous students’ papers, it became clear that making a go kart would not be an original idea. I determined the two aspects of a go kart that made it appealing to me, those being that is was fun and motorized, and continued my search for an alternative project. It was on a go kart parts website that the phrase “drift trike” first popped up. After watching videos of people bombing hills on motorless drift trikes, I was led to multiple instructional videos on how to outfit a drift trike with a gas engine for flatland use [1]. -

Victorian Rider Handbook Part 2

Keep away from troubles 46 Keep a grip 54 Riding at night 58 Loading up 62 Riding in a group 66 Looking after your bike 70 Staying Alive 44 Staying Alive Staying Alive Anticipation and skill make riding safer and enjoyable The one thing above all others that will keep you safer on the road is your attitude. You can learn as many skills as you like, and be the most technically skilled rider around, but you can throw it all away because you can’t be bothered thinking before you act. Make no mistake about it, the road is a dangerous place, especially on a bike. Staying alive while you are out there is your responsibility. You will find the VicRoads booklet,Discover Safe Riding, a useful guide for developing your skills. 45 Keep away from trouble It might sound simple, but what can’t get at you can’t hurt you. So it makes sense to stay as far away as possible from the things that can hurt you on the road. Survival space The consequences of an error, yours or someone else’s, can be very serious for you as a rider. Survival space is the best protection you can have. The more space you have around you, the more time you have to see trouble and work out a way of avoiding it. Of course, that only works if you keep your eyes open and your mind alert. In front This is the distance between your bike and the vehicle you are following, and you have control over it. -

Engineering Balance: the Conceptual Approach by Jonathan E

Engineering Balance: The Conceptual Approach by Jonathan E. Abbott Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Engineering in Mechanical Engineering at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2014 © Jonathan E. Abbott, MMXIV. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author.............................................................. Department of Mechanical Engineering January 17, 2014 Certified by. Anette (Peko) Hosoi Professor of Mechanical Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Anette (Peko) Hosoi Professor of Mechanical Engineering Chairman, Department Committee on Undergraduate Theses 2 Engineering Balance: The Conceptual Approach by Jonathan E. Abbott Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering on January 17, 2014, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Engineering in Mechanical Engineering Abstract This work presents a view of balance useful for mechanical engineers. Mechanical engineers often need to make quick intelligent decisions using conceptual and physi- cal understanding. The typical mechanical engineering instruction usually provides a good basis for \back of the envelope" calculations, especially for mechanical systems; however, one exception to this case is in the field of dynamics and control. Dynam- ics and control is generally taught with much math, modelling most systems with differential equations. Although math is useful for designing control systems, when designing products for people who act as sophisticated controllers the engineer needs a more general understanding of balance. This work presents a conceptual intuitive way to break the act of balance into distinct mechanisms and thereby quickly evaluate how a system balances. -

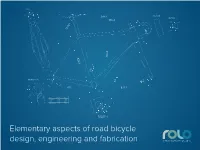

Elementary Aspects of Road Bicycle Design, Engineering

VIEW C 3 6 25 9,62 549,4 VIEW B-B SECTION - 376,4 B 16,08 5,50 8 149,7 72,82° 17,20 C B 562,4 522,9 A E E 10 5 27 150 SECTION A-A R8,20 74 46,3 R 10 9,46 32,50° 77,31° 411 574,1 A 141 147 153 brand 50teeth 53teeth Shimano 141mm 147mm 8,70 SRAM 141mm 147mm 25 Campagnolo 142mm 148mm R1,5 12 3,5° R7,6 6 5 R R 8,4 8,15 2 SECTION E-E SCALE 1 : 1 Elementary aspects of road bicycle design, engineering and fabrication © Motion Devices SA, 2015 © Motion Devices SA Page 1 Over the course of the last one hundred years, the design of the Contents diamond frame road racing bicycle has evolved surprisingly little. A quick look at frame building 2 Nonetheless, many riders complain about not feeling comfortable What has custom meant? 3 on their bicycles but do not always understand why that is the case. When is a monocoque a monocoque? 4 Few complain that their bicycles do not handle as they would wish, A quick background on carbon fiber 5 silently accepting that a new bicycle does not feel as intuitive as the Why a custom lay-up? 6 bicycles of their youth. They usually ascribe the difference to their It turns out that geometry is not as easy as it looks 7 rose colored backward looking glasses. The rule of thirds 8 Stack and reach explained 8 In fact, while correct bicycle design and engineering requires a The importance of being consistent 8 thorough understanding in order to produce a very high performing Top tube length 9 bicycle, it is not impossible to achieve. -

IN CONTROL.Indd

2 3 Dear motorcycle rider! The book you now hold in your hand is unique. freedom on your way towards unknown places. It is a gift from motorcycle riders to motorcycle We are today about 90.000 riders in Norway. riders. Motorcycle riding is first of all about the Every spring we swarm out on the roads as joy of life. The feeling of being on the road. Meet soon as the snow is gone. Eager to enjoy a new friends. Enjoy the man-machine togetherness riding season. More than 99% of us return on curvy roads. Feel the power of acceleration, happily home from adventure. But not all. the thrill of leaning into a curve. Or the calm, For motorcycle riding is a demanding sport. p u l s a t i n g sensation of A small rider error can result in serious injury. The accident could have been avoided if only small things had been done otherwise. Indeed, research shows that many a rider 2 3 ditches in situations where the bike itself could the rider’s own instinctive actions. Conscious have carried him safely through. But often the effort to learn precise riding techniques, rider disturbs the bike by inadequate action. and thus beat instinct, will inevitably lead to Faced with danger, a human being reacts increased joy and less trouble. instinctively. A lightning quick reaction intended To change working habits demands A motorcycle to avoid injury. Action that happens before perseverance. It takes humility to realize can do only we have time to think. Riding a bike, these that you may be wrong. -

2015 Training Manual

Copyright © 2015 by T revor Dech (Owner of Too Cool Motorcycle School Inc.) All rights reserved. This manual is provided to our students as a part of our Basic Motorcycle Course. Its contents are the property of Too Cool Motorcycle School Inc. and are not to be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without permission. Publish Date: Jan 10, 2015 Version: 2.6 Training: McMahon Stadium, South East Lot Classroom: Dalhousie Community Centre Phone: 403-202-0099 Website: www.toocoolmotorcycleschool.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Too Cool Motorcycle School Training Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS PART ONE ..................................................................................1 TYPES OF MOTORCYCLES ..........................................................................1 OFF-ROAD MOTORCYCLES .................................................................................................1 TRAIL ......................................................................................................................1 ENDURO...................................................................................................................2 MOTOCROSS ............................................................................................................2 TRIALS.....................................................................................................................2 DUAL PURPOSE.........................................................................................................2 ROAD BIKES .....................................................................................................................3 -

Bicycle and Motorcycle Dynamics - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 16/1/22 上午 9:00

Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 16/1/22 上午 9:00 Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics is the science of the motion of bicycles and motorcycles and their components, due to the forces acting on them. Dynamics is a branch of classical mechanics, which in turn is a branch of physics. Bike motions of interest include balancing, steering, braking, accelerating, suspension activation, and vibration. The study of these motions began in the late 19th century and continues today.[1][2][3] Bicycles and motorcycles are both single-track vehicles and so their motions have many fundamental attributes in common and are fundamentally different from and more difficult to study than other wheeled vehicles such as dicycles, tricycles, and quadracycles.[4] As with unicycles, bikes lack lateral stability when stationary, and under most circumstances can only remain upright when moving forward. Experimentation and mathematical analysis have shown that a bike A computer-generated, simplified stays upright when it is steered to keep its center of mass over its model of bike and rider demonstrating wheels. This steering is usually supplied by a rider, or in certain an uncontrolled right turn. circumstances, by the bike itself. Several factors, including geometry, mass distribution, and gyroscopic effect all contribute in varying degrees to this self-stability, but long-standing hypotheses and claims that any single effect, such as gyroscopic or trail, is solely responsible for the stabilizing force have been discredited.[1][5][6][7] While remaining upright may be the primary goal of beginning riders, a bike must lean in order to maintain balance in a turn: the higher the speed or smaller the turn radius, the more lean is required. -

The Mo T Orc Ycle Safety F

THE MOTORCYCLE SAFETY FOUNDATION BASIC RIDERCOURSE SM Edition 1.0, First Printing: March 2014 © 2014 Motorcycle Safety Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Motorcycle Safety Foundation® (MSF®). Under no circumstances may the material be reproduced for resale. Please send request by email to: [email protected]. Portions of this book may be reproduced by the Motorcycle Safety Foundation certified RiderCoaches solely to facilitate their presenting this MSF Basic RiderCourseSM. Under no circumstances may a RiderCoach reproduce this material in its entirety. The MSF Basic RiderCourse is based on years of scientific research and field experience. This current edition has been field-tested and has proven to be successful in developing the entry-level skills for riding in traffic. Through its various iterations, over seven million riders have been trained since 1973. The information contained in this publication is offered for the benefit of those who have an interest in riding motorcycles. In addition to the extensive research and field experience conducted by the MSF, the material has been supplemented with information from publications, interviews and observations of individuals and organizations familiar with the use of motorcycles and training. Because there are many differences in product design, riding styles, and federal, state and local laws, there may be organizations and individuals who hold differing opinions. Consult your local regulatory agencies for information concerning the operation of motorcycles in your area. -

URAL How to Ride

Introduction Motorcycle enthusiasts have been attaching sidecars to their machines since about 1895. Motorcycle/sidecar combinations are alternatively referred to as "rigs," "hacks," "chairs" or "outfits." While combinations continue to be only a small minority of motorcycles worldwide, sidecars are still being built and attached to today's motorcycles. There are probably more outfits on the road than ever before. There are all sorts of sidecar rigs in operation, including some that lean into corners and some with steerable sidecar wheels. But the majority of sidecar rigs are straightforward three-wheelers built by attaching a sidecar rigidly to a motorcycle. The URAL motorcycle/sidecar combinations have been built with the same basic frame arrangement for 55 years, although the operating systems have gradually been refined. There are two basic URAL sidecar combinations, one with a single driven rear wheel and a similar model with both the rear and sidecar wheels shaft-driven. Throughout this manual we will point out differences in handling and operating techniques for the different models. The most important lesson about motorcycle/sidecar combinations is that the resulting three-wheeler is neither a motorcycle nor an automobile, but an entirely different vehicle with very different operating characteristics. Even the veteran motorcyclist with hundreds of thousands of miles of three-wheeled experience becomes a novice when learning to pilot a hack for the first time. Scope The purpose of this manual is to assist the novice sidecar operator to learn how to drive a combination on the street. The manual includes both explanations of basic sidecar riding techniques and driving exercises the novice can practice to gradually build skill. -

Motorcycle Stability and Steering by Andy Townsend

Motorcycle Stability and Steering by Andy Townsend “Speed Stabilizes the motorcycle” and “press left, lean left, go left” are two phrases heard by students taking the MRC:RSS rider course. During the course students may be told to “trust us on this one...it REALLY works” Well, it DOES really work, but during the course there is little time to explain why speed DOES stabilize the motorcycle and yes, you DO press the left bar to initiate a turn to the left. So…here are explanations of motorcycle stability and steering! Although reading both sections will give a greater understanding of motorcycle dynamics, the sections do “stand alone”, so read either or both at your leisure! Motorcycle Stability Keeping balanced in a straight line, assuming the road is flat and there is no crosswind, is a matter of keeping the combined Center of Gravity of rider and motorcycle vertically above a line joining the contact patches where the front and rear tires touch the road. If the bike starts to lean there are two ways to correct this and restore the situation where the contact patch line is under the Center of Gravity: 1. Move the Center of Gravity OVER the new contact patch line. 2. Move the tire contact patch line back UNDER the new Center of Gravity. 3. Ever seen someone balance a bike that is NOT moving forward? The primary balance method is moving their body to try and maintain the Center of Gravity over the contact patch line...tricky! A much easier way to balance, once moving forward, is to use method 2: 4. -

Book of Abstracts

Front cover: “Levende Etalage Dag”, A view of the wall at Pluympot, Delft, April 2010. A Bicycle in Mosaic, a photo made by Shirley Elprama. Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Scientific and Organizing Committees ....................................................................................... 8 Sponsors ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Program ....................................................................................................................................... 9 More info about Venue, Wireless Network, Contact and Addresses ........................................ 16 Abstracts..................................................................................................................................... 17 Rider Control of a Motorcycle near to its Cornering Limits R. S. Sharp - University of Surrey, United Kingdom ................................................................. 18 Analysis of the Biomechanical Interaction between Rider and Motorcycle by Means of an Active Rider Model Valentin Keppler - Biomotion Solutions, Germany ................................................................... 20 Modeling Manually Controlled Bicycle Maneuvers Ronald Hess, Jason K. Moore, Mont Hubbard and Dale L. Peterson, University of California, Davis, USA ................................................................................................................................ -

Sidecar/Trike Operator Manual

DEPARTMENT OF LICENSING Sidecar/Trike Operator Manual dol.wa.gov WASHINGTON MOTORCYCLE SAFETY PROGRAM Who needs motorcycle safety education? . .1 How are new riders trained? . .2 Added benefits . .2 Where can I find a course? . .2 What will the course cost? . .3 Instruction permit . .3 Motorcycle and three-wheeler endorsements . .3 Fees . .4 Equipment requirements . .4 PREPARING TO RIDE Wear the Right Gear . .7 Helmet use . .7 Helmet selection . .8 Eye and face protection . .9 Clothing . .10 Know Your Three-Wheeler . .11 Operating differences . .11 The right three-wheeler for you . .12 Borrowing and lending . .12 Get familiar with the three-wheeler controls . .13 Check your three-wheeler . .14 Know Your Responsibilities . .15 Risk Awareness . .16 RIDE WITHIN YOUR ABILITIES Basic Vehicle Control . .17 Tip over lines . .17 Body position . .18 Shifting gears . .18 Braking . .19 Turning . .20 Hills . .21 Keeping Your Distance . .22 Following another vehicle . .22 Being followed . .23 Passing and being passed . .24 Passing . .24 Being passed . .24 Lane sharing . .25 Merging cars . .25 i Cars alongside . .25 Freeway riding . .26 Riding Strategy . .26 Search ahead . .27 Locate hazards . .27 Anticipate . .27 Decide . .28 Evasive action . .28 Intersections . .29 Blind intersections . .31 Passing parked cars . .31 Increasing Conspicuity . .32 Clothing . .33 Headlight . .33 Signals . .33 Brake light . .34 Using your mirrors . .34 Head checks . .35 Horn . .36 Riding at night . .36 Collision Avoidance and Evasive Maneuvers . .37 Quick stops . .38 Swerving or turning quickly . .39 Cornering . .40 Handling Dangerous Surfaces . .42 Uneven surfaces and obstacles . .43 Slippery surfaces . .43 Railroad tracks, trolley tracks, and pavement seams . .45 Grooves and gratings .