Athena's Gate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAW 2018 E-Book.Pdf

IT’S ALL WRITE 2018 0 1 Thank you to our generous sponsors: James Horton for the Arts Trust Fund & Loudoun Library Foundation, Inc. Thank you to the LCPL librarians who selected the stories for this book and created the electronic book. These stories are included in their original format and text, with editing made only to font and spacing. 2 Ernest Solar has been a writer, storyteller, and explorer of some kind for his entire life. He grew up devouring comic books, novels, any other type of books along with movies, which allowed him to explore a multitude of universes packed with mystery and adventure. A professor at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland, he lives with his family in Virginia. 3 Table of Contents Middle School 1st Place Old Blood ........................................................... 8 2nd Place Hope For Life ................................................. 22 3rd PlaceSad Blue Mountain ......................................... 36 Runner Up Oblivion ...................................................... 50 Runner Up In the Woods ............................................. 64 Middle School Honorable Mentions Disruption ........................................................................ 76 Edge of the Oak Sword ................................................. 84 Perfection .......................................................................... 98 The Teddy ...................................................................... 110 Touch the Sky............................................................... -

CHARTED TERRITORY by NETA GORDON Thesis Submitted to The

CHARTED TERRITORY Women Nriting Genealogy in Recent Canadian Fiction by NETA GORDON Thesis submitted to the Department of English In conformity with the requirements fx The degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen's University Kingston. Ontario. Canada November. 200 1 Copyright O Neta Gordon 2001 uisiaans and Acquisitions et 3-Bi mgogrPphic Services seMees WliraphQues The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclwive licence aiiowing the exclusive permettant à la National Li- of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownetshtp of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette dièse. thesis nor substantial extracts fbmit Ni la thése ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This dissertation argues that the recent refashioning of the genealogical plot by Canadian women entails a dual process whereby, on the one hand, the idea of family is radically redefined and, on the other hand, the conservative traditions of family are in some way recuperated. For my analysis of the multi-generational family history, 1 develop a complex critical framework which demonstrates that the organizing principles goveming any particular conception of family will also influence the way that family's story is nmted. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

5 One Last Look Around — Tim Wellman 12 the Undying Game — C

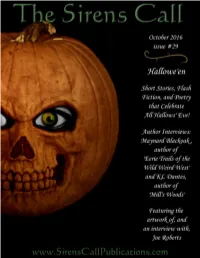

1 Contents Fiction 5 One Last Look Around — Tim Wellman 12 The Undying Game — C. Cooch 16 Halloween Hunting — J.W. Grace 18 The Hairy Ones — Terry M. West 21 Extreme Halloween — Jill Hand 27 Jack — Otis Moore 31 Dead Man’s Hill — Marlena Frank 35 Spoiled — Nicolas Rose 40 Leaves — Diane Arrelle 45 Night of the Witch — Larry W. Underwood 48 Crime Scene — James WF Roberts 50 Halloween Memories — L. Page Hamilton 53 The Sexy Cats Survival Guide — Andrew Robertson 58 Hunger — J. M. Van Horn 61 Still of Night — Rory J. Roche 66 Not Cavities — Patrick Loveland 88 Saving Grace — Kevin Holton 93 Leftovers — David J. Gibbs 98 Trick — Kahramanah 102 The Desecraters of Samhaim — Jacob Mielke 107 Slugger Saves — Calvin Demmer 110 The Madness Within — Lucretia Richmond 111 The End… — Mark Steinwachs 116 The Pumpkin Gallery — Nick Manzolillo 122 Superstition — Patrick Winters 125 Concealed — Madeline Mora-Summonte 127 All Hallows Eve — R. J. Meldrum 130 Danse Macabre — B. David Spicer 137 The Melancholy Raven — Jessica Curtis 140 The Seed — James S. Austin 146 Still — James WF Roberts 146 Halloween Monsters — Matthew Wilson 152 Money or Your Soul — Stephen Crowley 2 Poetry 76 Trigger Tree — Carl Palmer 79 Barnaby Braxton’s Never-Ending Smile — Stuart Conover 80 Childish Fears — Stacy Fileccia 80 Terror’s Game — Stacy Fileccia 82 Devil's Night — Megan O’Leary 83 T’was a Full Moon Night, October 31st — James WF Roberts Features 73 Interview with KL Dantes, Author of Mill’s Woods 86 Interview with Artist Joe Roberts 160 Interview with Maynard Blackoak, Author of Eerie Trails of the Wild Weird West 162 Excerpt from Eerie Trails of the Wild Weird West Artwork 4 Ghosts 49 Black Christmas 78 Zombie Apocalypse 85 Wonder Woman 97 Nightmares Reign 115 Ghost 136 The Incubus Horror 167 Credits 3 4 One Last Look Around | Tim Wellman Stupid Leanna Thomas! Me, I mean. -

Complete Invincible Library Volume 3 Ebook Free Download

COMPLETE INVINCIBLE LIBRARY VOLUME 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Kirkman | 768 pages | 13 Dec 2011 | Image Comics | 9781607064213 | English | Fullerton, United States Complete Invincible Library Volume 3 PDF Book Read the story in a whole new way, never before collected together in one single volume. Up until this point, Invincible has been working for the Global Defense agency. The Walking Dead [] - Journey Begins 5 copies. Read a little about our history. Brit, Volume 1: Old Soldier 54 copies. When Gary Hampton is mauled and left for dead, his life takes a drastic turn! May 29, Chad rated it it was amazing Shelves: Volume 3 - 1st printing. And where in the worldis Derek''s mother? Meanwhile, back at the prison, the rest of the survivors come to grips with the fact Rick may be dead. Almost pages of pure Invincible goodness. This is why I started reading Invincible, for this moment and let me tell you The sudden violence in the previous book wasn't a fluke, and the complete plot turn-around sucked me in. Haunt Volume 1 Author 45 copies, 1 review. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Woah, boy. Invincible, Compendium Three by Robert Kirkman. Invincible 4 1 copy. Nathan Cole was the only one to have never given up searching the apocalyptic hellscape of Oblivion. Make way for The League of Losers! It's here: the second massive paperback collection… More. The Walking Dead - 1. The town of Rome, West Virginia has always been a hotbed of demonic activity. The tone and the humor is nice to balance it and the human drama is the best part about this book. -

Press Layout

2 Vol. XXXI, Issue 2 | Wednesday, September 30, 2009 news Obama, Paterson, Makin’ War Not Love In a shock - tempt to verbally one up their opponent. ing turn of “So that’s how it’s going to be, huh? Brother against By Nick Statt events involv - brother?” Paterson said after being told that Obama ing the recent wouldn’t be opposed to “socking him once or twice in the controversy mouth.” Paterson finished out the surprisingly emotional over New York Governor David Paterson’s decision to run interview with NBC’s David Gregory by saying, “That for governor, President Obama called Gov. Paterson a “jack - grey-haired grandpa couldn’t touch me. I’m like Dare - ass on Monday, September 21. devil. My acute hearing would carry me all day.” “I mean, sometimes I just wonder what he’s doing up The back and forth from the President and New there. He’s certainly not winning any popularity awards and York’s heavily disliked governor has created an enormous then just decides to totally ignore my request for him to pull buzz on the commentator circuit. Jelly donut-human hy - out,” Obama said casually after the first portion of his inter - brid Rush Limbaugh, famous for getting his start on the view with Terry Moran of NBC. “So does that count as the Food Network by questioning Rachel Ray’s sexuality, has first question?” Moran responded. “I, I hear you – I agree called Paterson’s comments in the Gregory interview as with you. He’s a jackass. He’s also legally blind and in all hon - pulling the “competitive race/physical disability card.” The esty I just can’t have that anymore,” Obama whispered, term, recently coined by Limbaugh himself, accuses Pa - As the week wraps up, President Obama has voiced fur - thinking that his off the record comments would stay terson of feeling both that he has to compete with Obama ther frustration. -

International Festival of Comics, Animation, Cinema, and Games

INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF COMICS, ANIMATION, CINEMA, AND GAMES Ryan Ottley XXV Edition Golden Romics In recognition of the great artist behind The Amazing Spider-Man and Invincible and a career dedicated to superheroes Ryan Ottley, artist of the superhero series Invincible, created by Robert Kirkman and Cory Walker, and The Amazing Spider-Man, will be awarded the Golden Romics in the next edition of Romics (April 4 – 7). This will be a unique opportunity to meet such a great international figure and celebrate his concluding volume of Invincible, which will bring the monthly edition to a close in January 2020. The final chapter of the saga will be celebrated with the variant edition of monthly issue 64 of Invincible, presented exclusively at Romics and dedicated to his presence in Rome. Ryan Ottley is one of the most important comic book artists of contemporary American comics. He is best known for his work on Invincible and, most recently, The Amazing Spider-Man. Enthralled at the age of 15 by an issue of Amazing Spiderman (drawn by Todd McFarland) that his cousin Bryan had given him, Ryan Ottley immediately realized that this was the path he wanted to follow. After debuting as an artist (and co-creator) of the web-strip Bicycle Delivery Boy, he met Robert Kirkman, creator of the cult saga The Walking Dead. Ottley then went on to draw the first five issues of Haunt – a superhero series by Image Comics, created by Kirkman and Todd McFarlane – and then moved on to drawing for the regular Invincible series. From that moment on, Ottley’s life was changed and he established his name as one of the most interesting players in American comics. -

In This Issue Non-Compliance T Hird World by Taylor Boulware

Ay LiterAr QuArterLy October 2015 X Vol. 5. No. 4 s pecial Focus: the edge of Difference in Comics and Graphic novels Essays GuEst Editor: tom FostEr Out from the Underground by susan simensky Bietila Gender, Trauma, and Speculation in Moto Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas by Regina Yung Lee Finder; Finder; Fan Culture and in this issue Non-Compliance t hird World hird by taylor Boulware GrandmothEr maGma Trying On Sex: Tits & Clits Comix X by Roberta Gregory Carla Carla Book rEviEws s Jennifer’s Journal: The Life peed M of a SubUrban Girl, Vol. 1 by Jennifer Cruté c n Ava’s Demon e il by Michelle Czajkowski Supreme: Blue Rose by Warren ellis and tula Lotay The Secret History of Wonder Woman by Jill Lepore Ms. Marvel, Volumes 1/2/3 created by G. Willow Wilson and “since its launch in 2011 The Cascadia Subduction Zone has emerged as one Adrian Alphona of the best critical journals the field has to offer.” h Jonathan McCalmont, February 18, 2013, hugo Ballot nomination FEaturEd artist $5.00 Carla speed Mcneil Managing Editor Ann Keefer Reviews Editor Nisi Shawl vol. 5 no. 4 — October 2015 Features Editor L. Timmel Duchamp GuEst Editor: tom FostEr Arts Editor Kath Wilham Essays Out from the Underground h $5.00 by Susan Simensky Bietila 1 Gender, Trauma, and Speculation in Moto Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas by Regina Yung Lee h 5 Fan Culture and Non-Compliance by Taylor Boulware h 9 GrandmothEr maGma Trying On Sex: Tits & Clits Comix by Roberta Gregory h 14 Book rEviEws Jennifer’s Journal: The Life of a SubUrban Girl, Vol. -

Olympians Teachers' Guide

Olympians Teachers’ Guide Introduction Many of our modern political, economic, and philo- sophical systems are rooted in Ancient Greek culture. The Ancient Greeks had one of the earliest known democracies, a rich literary tradition, and unique art and architecture, which we see copied all over the world and still used symbolically. Greek philosophy, medicine, science, and technology were all ahead of their time, and a familiarity with them is essential for understanding the world today—if for no other reason ABOUT THE OLYMPIANS BOOKS than because so much of our own culture, and even language, is based on Ancient Greek words and ideas. The myths and gods of Ancient Greece shine a bright HC ISBN 978-1-59643-625-1 . PB ISBN: 978-1-59643-431-8 $9.99 PB/$16.99 HC . 7.5 x 10 . Full Color Graphic Novel light onto the culture of one of the world’s oldest ZEUS: KING OF THE GODS known civilizations. Because of the influence Ancient The strong, larger-than-life heroes of Zeus: King of Greek culture has on our world today, studying the the Gods can summon lightning, control the sea, turn myths can help explain current beliefs about science, invisible, and transform themselves into any animal democracy, and religion. Myths are, by definition, ficti- they choose. This first book of the series introduces tious. But the origin stories of the Ancient Greeks were Zeus, the ruler of the Olympian pantheon, and tells real to them—as real as our understanding of how the his story from his boyhood to his adventure-filled Earth began. -

ELA Grade 9 Unit of Study

Getting to the Core English Language Arts Grade 9 Unit of Study Introduction to Mythology STUDENT RESOURCES Final Revision: June 4, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Pages Lesson 1: What are the criteria of a myth? What patterns exist in myths? Resource 1.1 Anticipatory Guide: Thinking about My World 1 Resource 1.2 Myths and Mythology 2 Resource 1.3 Three Criteria of a Myth 3 Resource 1.4 Transcript for TED Talks Video + Essential Questions 4-5 Resource 1.5 Patterns in Mythology Matrix 6 Resource 1.6 Evidence of Patterns Matrix 7 Resource 1.7 “How the Crocodile Got Its Skin” text 8 Resource 1.8 “Arachne the Spinner” text 9-11 Resource 1.9 Pre-assessment: Writing an Argument 12 Resource 2.1 Warm-up: Responding to Video Clip 13 Resource 2.2 A Summary of How the World Was Made 14-15 Resource 2.3A-E “The Beginning of Things” Parts 1- 5 16-20 Resource 2.4 Collaborative Annotation Chart – “Beginning” Part I 21 Resource 2.5 Collaborative Annotation Chart – “Beginning” Part_ 22 Resource 2.6 Myth Comparison Matrix: “The Beginning of Things” 23 Resource 2.7 Writing an Argument #2 24-25 Resource 2.8 Model Paragraph (Writing Outline) 26 Resource 3.1 Cyclops Painting & Quick-Draw 27-28 Resource 3.2 PowerPoint Notes: Introduction to Epic/Myth/Cyclops 29-32 Resource 3.3 Collaborative Annotation Chart – “The Cyclops” 33 Resource 3.4 Section Analysis Chart 34-41 Resource 3.5A Cyclops Comic Strip Planning Sheet 42-43 Resource 3.6 Cyclops Comic Strip Gallery Walk: Focused Questions 44-45 Resource 3.7 Evidence of Cultural Beliefs, Values & Patterns Matrix 46 Resource 3.8 Argumentative Writing Task #3 47-48 Resource 4.1 “Patterns” Project Instructions 49 Resource 4.2 “Patterns” Project Rubric 50 Resource 4.3 “Patterns” Project Example 51 ELA Grade 9 Intro to Mythology, Lesson 1 Resource 1.1 Anticipatory Guide: Thinking about My World Opinion Explanation Agree Disagree Patterns help us 1. -

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM On11/01/20, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

11/01 - Day of the Dead Comics & Collectible Toys Special 11/1/2020 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on11/01/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Rules & Regulations 1 13 Captain America & Superman Model Kits 1 1/8 scale kits. Assembled and painted. Superman's cape is broken 2 What If? #10 Jane Foster Thor/Key 1 1st appearance of Thordis, Jane Foster after having found Mjolnir. but could be reglued. Otherwise appears to be complete. VF- condition. 14 Tales of Suspense #91 (1967) 1 Gene Colan cover! FN+ condition 3 TEEBO Star Wars RotJ (1983) Kenner NOC! 1 Figure is brand new, never opened, still ON CARD. Card is 15 Movie & TV Show Clothing Lot 1 UNPUNCHED, although there is some minor wear around punch. Scarfs, t-shirts, and hats. Jurassic Park, Marvel, The Goonies, and Card itself is in very good condition with minor storage wear. more! The T-shirts are 3XL except for the Firefly shirt is a 2XL. Bubble is yellowed, but overall great condition with no dents or 16 Early Image Collector Packs Lot 1 cracks. Complete 4 issue mini-series lot of (2) WildC.A.T.S and 4 She-Hulk Bronze Group of (8) 1 Youngblood. -

The Devil in the White City : Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America / Erik Larson.—Ed

The DeDevviill iinn thethe WWhithitee CityCity This book has been optimized for viewing at a monitor setting of 1024 x 768 pixels. Chicago, 1891. Also by Erik Larson Isaac’s Storm Lethal Passage The Naked Consumer TheThe DeDevvilil inin thethe WWhithitee CityCity Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America Erik Larson Crown Publishers • New York Illustration credits appear on page 433. Copyright © 2003 by Erik Larson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by Crown Publishers, New York, New York. Member of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. www.vintagebooks.com CROWN is a trademark and the Crown colophon is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Design by Leonard W. Henderson Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Larson, Erik. The devil in the white city : murder, magic, and madness at the fair that changed America / Erik Larson.—ed. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Mudgett, Herman W., 1861–1896. 2. Serial murderers—Illinois—Chicago— Biography. 3. Serial murders—Illinois—Chicago—Case studies. 4. World’s Columbian Exposition (1893 : Chicago, Ill.) I. Title. HV6248.M8 L37 2003 364.15'23'0977311—dc21 2002154046 eISBN 1-4000-7631-5 v1.0 To Chris, Kristen, Lauren, and Erin, for making it all worthwhile —and to Molly, whose lust for