University of Alberta Alice Walker: a Litemy Genealogist by Paege

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sweat: the Exodus from Physical and Mental Enslavement to Emotional and Spiritual Liberation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation Aqueelah Roberson University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Roberson, Aqueelah, "Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3319. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3319 SWEAT: THE EXODUS FROM PHYSICAL AND MENTAL ENSLAVEMENT TO EMOTIONAL AND SPIRITUAL LIBERATION by AQUEELAH KHALILAH ROBERSON B.A., North Carolina Central University, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2007 © 2007 Aqueelah Khalilah Roberson ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to showcase the importance of God-inspired Theatre and to manifest the transformative effects of living in accordance to the Word of God. In order to share my vision for theatre such as this, I will examine the biblical elements in Zora Neale Hurston’s short story Sweat (1926). I will write a stage adaptation of the story, while placing emphasis on the biblical lessons that can be used for God-inspired Theatre. -

Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository English Faculty Publications English 1983 Zora Neale Hurston Daryl Cumber Dance University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/english-faculty-publications Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dance, Daryl Cumber. "Zora Neale Hurston." In American Women Writers: Bibliographical Essays, edited by Maurice Duke, Jackson R. Bryer, and M. Thomas Inge, 321-51. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 12 DARYL C. DANCE Zora Neale Hurston She was flamboyant and yet vulnerable, self-centered and yet kind, a Republican conservative and yet an early black nationalist. Robert Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977 There is certainly no more controversial figure in American literature than Zora Neale Hurston. Even the most common details, easily ascertainable for most people, have been variously interpreted or have remained un resolved issues in her case: When was she born? Was her name spelled Neal, Neale, or Neil? Whom did she marry? How many times was she married? What happened to her after she wrote Seraph on the Suwanee? Even so immediately observable a physical quality as her complexion sparks con troversy, as is illustrated by Mary Helen Washington in "Zora Neale Hurston: A Woman Half in Shadow," Introduction to I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . -

Mobility and the Literary Imagination of Zora Neale Hurston and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Narratives Of Southern Contact Zones: Mobility And The Literary Imagination Of Zora Neale Hurston And Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Kyoko Shoji Hearn University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hearn, Kyoko Shoji, "Narratives Of Southern Contact Zones: Mobility And The Literary Imagination Of Zora Neale Hurston And Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 552. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/552 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATIVES OF SOUTHERN CONTACT ZONES: MOBILITY AND THE LITERARY IMAGINATION OF ZORA NEALE HURSTON AND MARJORIE KINNAN RAWLINGS A Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by KYOKO SHOJI HEARN December 2013 Copyright Kyoko Shoji Hearn 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the literary works of the two Southern women writers, Zora Neale Hurston and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, based on the cultural contexts of the 1930s and the 1940s. It discusses how the two writers’ works are in dialogue with each other, and with the particular historical period in which the South had gone through many social, economical, and cultural changes. Hurston and Rawlings, who became friends with each other beyond their racial background in the segregated South, shared physical and social mobility and the interest in the Southern folk cultures. -

Their Eyes Were Watching God and the Revolution of Black Women

1 Their Eyes Were Watching God and the Revolution of Black Women Ashley Begley Professor Angelo Robinson 2 It did not pay to be a woman during the Harlem Renaissance. Women’s work was seen as inferior and the women themselves were often under-valued and deemed worthless, meant only to be controlled by the patriarchal society. To be a black woman meant that this societal suffocation and subjugation were doubled, for not only did a black woman have to overcome the inequalities faced by all women, she also had to fight the stereotypes that have been thrust upon her since slavery. Many authors of the Harlem Renaissance, especially Zora Neale Hurston in her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, wrote about black women in order to defy stereotypes that were commonly held as truth. Through their writings, these authors explored how the institutions of race and gender interact with each other to create a unique experience for black women of the Harlem Renaissance. It seems natural that the literature of the Harlem Renaissance is supposed to explore and solve the race problem. In fact, W.E.B. DuBois, one of the deans of the Harlem Renaissance, said, “Whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy” (103). Some authors, such as Jesse Redmon Fauset, cleaved to this idea and made it the main purpose of their work. Fauset’s novel There is Confusion portrays Joanna and Maggie as pushing the boundaries set for them by racial discrimination and gender inequity. -

Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector

The Artist and the Folk: Politics, Identity and Humor in the Work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Sholem Aleichem and Mordkhe Spector by Alexandra Hoffman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Anita Norich, Chair Professor Sandra Gunning Associate Professor Mikhail Krutikov Associate Professor Christi Merrill Associate Professor Joshua Miller Acknowledgements I am delighted that the writing process was only occasionally a lonely affair, since I’ve had the privilege of having a generous committee, a great range of inspiring instructors and fellow graduate students, and intelligent students. The burden of producing an original piece of scholarship was made less daunting through collaboration with these wonderful people. In many ways this text is a web I weaved out of the combination of our thoughts, expressions, arguments and conversations. I thank Professor Sandra Gunning for her encouragement, her commitment to interdisciplinarity, and her practical guidance; she never made me doubt that what I’m doing is important. I thank Professor Mikhail Krutikov for his seemingly boundless references, broad vision, for introducing me to the oral history project in Ukraine, and for his laughter. I thank Professor Christi Merrill for challenging as well as reassuring me in reading and writing theory, for being interested in humor, and for being creative in not only the academic sphere. I thank Professor Joshua Miller for his kind and engaged reading, his comparative work, and his supportive advice. Professor Anita Norich has been a reliable and encouraging mentor from the start; I thank her for her careful reading and challenging comments, and for making Ann Arbor feel more like home. -

Looking for Zora Neale Hurston on the Florida Federal Writer's

!1 Race and Reputation: Looking for Zora Neale Hurston on the Florida Federal Writer’s Project Katharine G. Haddad Honors History Thesis Dr. Lauren Pearlman April 5, 2017 !2 Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................................Page 3 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 4-8 Chapter One: Foundations of the Federal Writer’s Project........................................................9-14 Chapter Two: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston........................................................................15-27 Chapter Three: Flaws of the Florida Chapter...........................................................................28-38 Chapter Four: Hurston vs. Racial Discrimination………………………………………...….39-48 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….49-53 !3 Abstract This research looks at the life and work of Zora Neale Hurston, specifically her time as part of the Florida chapter of the Federal Writer’s Project (FWP), a New Deal initiative. Most prior research on the time Hurston spent on the project focuses on her relationship with Stetson Kennedy and their joint collection of Florida folklore. However, this focus overlooks the themes of racial discrimination which I argue plagued the Florida chapter of the FWP from the top down. This research draws heavily upon both primary and secondary sources including published letters from the -

Harold Bloom (Editor)-Zora Neale Hurston (Blooms Modern Critical

Bloom’s Modern Critical Views African American Samuel Taylor John Keats Poets: Coleridge Jamaica Kincaid Wheatley–Tolson Joseph Conrad Stephen King African American Contemporary Poets Rudyard Kipling Poets: Julio Cortázar Milan Kundera Hayden–Dove Stephen Crane Tony Kushner Edward Albee Daniel Defoe Ursula K. Le Guin Dante Alighieri Don DeLillo Doris Lessing Isabel Allende Charles Dickens C. S. Lewis American and Emily Dickinson Sinclair Lewis Canadian Women E. L. Doctorow Norman Mailer Poets, John Donne and the Bernard Malamud 1930–present 17th-Century Poets David Mamet American Women Fyodor Dostoevsky Christopher Poets, 1650–1950 W. E. B. DuBois Marlowe Hans Christian George Eliot Gabriel García Andersen T. S. Eliot Márquez Maya Angelou Ralph Ellison Cormac McCarthy Asian-American Ralph Waldo Emerson Carson McCullers Writers William Faulkner Herman Melville Margaret Atwood F. Scott Fitzgerald Arthur Miller Jane Austen Sigmund Freud John Milton Paul Auster Robert Frost Molière James Baldwin William Gaddis Toni Morrison Honoré de Balzac Johann Wolfgang Native-American Samuel Beckett von Goethe Writers The Bible George Gordon, Joyce Carol Oates William Blake Lord Byron Flannery O’Connor Jorge Luis Borges Graham Greene George Orwell Ray Bradbury Thomas Hardy Octavio Paz The Brontës Nathaniel Hawthorne Sylvia Plath Gwendolyn Brooks Robert Hayden Edgar Allan Poe Elizabeth Barrett Ernest Hemingway Katherine Anne Browning Hermann Hesse Porter Robert Browning Hispanic-American Marcel Proust Italo Calvino Writers Thomas Pynchon Albert Camus Homer Philip Roth Truman Capote Langston Hughes Salman Rushdie Lewis Carroll Zora Neale Hurston J. D. Salinger Miguel de Cervantes Aldous Huxley José Saramago Geoffrey Chaucer Henrik Ibsen Jean-Paul Sartre Anton Chekhov John Irving William Shakespeare G. -

In the Work of Zora Neale Hurston by Jennifer Lewis

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/65214 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Variations Around a Theme: The Place of Eatonville in the Work of Zora Neale Hurston by Jennifer Lewis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English University of Warwick, Department of English and Comparative Literature March 2001 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 111 Abstract IV Preface V Introduction 1 'Slipping into Neutral' in Mules and Men 33 'Four Walls Squeezing Breath Out': The Limitations of Place in Their Eyes Were Watching God 89 'The Jagged Hole Where My Home Used To Be': Dust Tracks on a Road 148 Conclusion 210 Bibliography 217 11 Acknowledgements My grateful thanks to Helen Taylor for her guidance, support and friendship over the last five years. Thanks also to Bridget Bennett, Liz Cameron, Cheryl Cave, Gill Frith, Rebecca Lemon, Emma Mason, Tracey Potts, Jane Treglown and all my colleagues at Warwick. I am especially indebted to Rosemary and Robert Lewis, Sarah and Ken Elliott, Margaret, Brian and Richard Welsh for caring for my daughter so often and so well. Finally, thanks go to Karen and Stephen Williams for their assistance in printing this thesis. -

•Œhe Can Read My Writing but He Shoâ•Ž Canâ•Žt Read My Mindâ•Š

Sarah Lawrence College DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence Women's History Theses Women’s History Graduate Program 5-2015 “He can read my writing but he sho’ can’t read my mind”: Zora Neale Hurston and the Anthropological Gaze Natasha Tatiana Sanchez Sarah Lawrence College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sanchez, Natasha Tatiana, "“He can read my writing but he sho’ can’t read my mind”: Zora Neale Hurston and the Anthropological Gaze" (2015). Women's History Theses. 5. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/womenshistory_etd/5 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s History Graduate Program at DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's History Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SarahLawrence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “He can read my writing but he sho’ can’t read my mind”: Zora Neale Hurston and the Anthropological Gaze Natasha Tatiana Sanchez Submitted in partial completion of the Master of Arts Degree at Sarah Lawrence College May 2015 1 Abstract “He can read my writing but he sho’ can’t read my mind”: Zora Neale Hurston and the Anthropological Gaze Natasha Sanchez This thesis explores the life and anthropological merits of Zora Neale Hurston’s literary works. I focus specifically on Hurston’s autobiography Dust Tracks on a Road to bring to light her critique of Western society. This thesis argues that Hurston purposefully utilized anthropology as a tool to switch the anthropological gaze upon white Western culture, thereby constructing the West as “other.” She masterfully bridges the gap between two disciplines: literature and anthropology. -

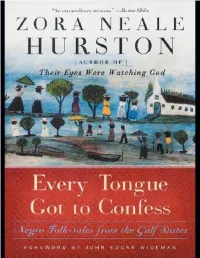

Every Tongue Got to Confess

ZORA NEALE HURSTON Every Tongue Got to Confess Negro Folk-tales from the Gulf States Foreword by John Edgar Wideman Edited and with an Introduction by Carla Kaplan Contents E-Book Extra The Oral Tradition: A Reading Group Guide Every Tongue Got to Confess Foreword by John Edgar Wideman Introduction by Carla Kaplan A Note to the Reader Negro Folk-tales from the Gulf States Appendix 1 Appendix 2 Appendix 3 “Stories Kossula Told Me” Acknowledgments About the Author Praise By Zora Neale Hurston Credits Copyright About the Publisher Acknowledgments The estate of Zora Neale Hurston is deeply grateful for the contributions of John Edgar Wideman and Dr. Carla Kaplan to this publishing event. We also thank our editor Julia Serebrinsky, our publisher Cathy Hemming, our agent Victoria Sanders, and our attorney Robert Youdelman who all work daily to support the literary legacy of Zora Neale Hurston. Lastly, we thank those whose efforts past and present have been a part of Zora Neale Hurston’s resurgence. Among them are: Robert Hemenway, Alice Walker, the folks at the MLA, Virginia Stanley, Jennifer Hart, Diane Burrowes and Susan Weinberg at HarperCollins Publishers, special friends of the estate Imani Wilson and Kristy Anderson, and all the teachers and librarians everywhere who introduce new readers to Zora every day. Foreword With the example of her vibrant, poetic style Zora Neale Hurston reminded me, instructed me that the language of fiction must never become inert, that the writer at his or her desk, page by page, line by line, word by word should animate the text, attempt to make it speak as the best storytellers speak. -

Chapter 1 Life

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-67095-1 - The Cambridge Introduction to Zora Neale Hurston Lovalerie King Excerpt More information Chapter 1 Life Born under the sign of Capricorn on January 7, 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, Zora Neale Hurston was the sixth child and second daughter of John Hurston (1861–1918) and Lucy Ann Potts Hurston (1865–1904). Hurston’s biographers tell us that her name was recorded in the family bible as Zora Neal Lee Hurston; at some point an “e” was added to “Neal” and “Lee” was dropped. Though she was born in Notasulga, Hurston always called Eatonville, Florida, home and even – though perhaps unwittingly, because her family relocated to Eatonville when Zora was quite young – named it as her birthplace in her autobiography. Eatonville has become famous for its long association with Hurston; since 1991 it has been the site of the annual multi-disciplinary Zora Neale Hurston Festival of the Arts and Humanities (ZORA! Festival), which lasts for several days. The festival’s broad objective is to call attention to contributions that Africa- derived persons have made to world culture; however, its narrower objective is to celebrate Hurston’s life and work along with Eatonville’s unique cultural history. Hurston’s family moved to Eatonville in 1893. Her father, John Hurston, was the eldest of nine children in an impoverished sharecropper family near Notasulga; during his lifetime, he would achieve substantial influence in and around Eatonville as a minister, carpenter, successful family man, and local politician. His parents, Alfred and Amy Hurston, were, like wife Lucy’s parents, Sarah and Richard Potts, formerly enslaved persons. -

Zora Neale Hurston

Notable African American Writers Sample Essay: Zora Neale Hurston Born: Eatonville, Florida; January 7, 1891 Died: Fort Pierce, Florida; January 28, 1960 Long Fiction: Jonah's Gourd Vine, 1934; Their Eyes Were Watching God, 1937; Moses, Man of the Mountain, 1939; Seraph on the Suwanee, 1948. Short Fiction: Spunk: The Selected Short Stories of Zora Neale Hurston, 1985; The Complete Stories, 1995. Drama: Color Struck, pb. 1926; The First One, pb. 1927; Mule Bone, pb. 1931 (with Langston Hughes); Polk County, pb. 1944, pr. 2002. Nonfiction: Mules and Men, 1935; Tell My Horse, 1938; Dust Tracks on a Road, 1942; The Sanctified Church, 1981; Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings, 1995; Go Gator and Muddy the Water: Writings, 1999 (Pamela Bordelon, editor); Every Tongue Got to Confess: Negro Folktales from the Gulf States, 2001; Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, 2002 (Carla Kaplan, editor). Miscellaneous: I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader, 1979 Achievements Zora Neale Hurston is best known as a major contributor to the Harlem Renaissance literature of the 1920's. Not only was she a major contributor, but also she did much to characterize the style and temperament of the period; indeed, she is often referred to as the most colorful figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Though the short stories and short plays that she generated during the 1920's are fine works in their own right, they are nevertheless apprentice works when compared to her most productive period, the 1930's.