Every Tongue Got to Confess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Deronda 20 Sarah E

palaver e /p ‘læv r/e n. A talk, a discussion, a dialogue; (spec. in early use) a conference between African tribes-people and traders or travellers. v. To praise over-highly, flatter; to ca- jole. To persuade (a person) to do some- thing; to talk (a person) out of or into something; to win (a person) over with palaver. To hold a colloquy or conference; to parley or converse with. Masthead | Table of Contents | Fall 2013 Fall 2013 Founding Editors We the People of Walmart 4 Finance Students Performance in the United Sarah E. Bode Lauren B. Evans States and Spain: Contrasts and Similarities Ashley Hudson 51 Coney Island Dreaming 7 Charles Wolfe Melanie Whithaus Executive Editor Chief Copy Editor A Systematic Evaluation of Empathy in Dr. Patricia Turrisi Jamie Joyner Been to Hell and Now I’m Back Again: Contemporary Society 58 The Songwriting of Steve Earle 11 Gregory Hankinson Contributing Editors Copy Editors Brian Caskey Michelle Bliss Lauren B. Evans What Would Aristotle Say About Bill Caporales 16 Clinton? Or Why We Excuse Moral Dr. Theodore Burgh Katja Huru Doctorcitos 17 Weakness 64 Dr. Carole Fink Megan Slater Bolivia 18 Rob Wells Ashley Hudson Charlene Eckels Courtney Johnson Staff Readers Exiled from Truth: An Interview with Dr. Marlon Moore Amanda Coffman Gwendolen Harleth: The Extraordinary Dmitry Borshch 68 Dr. Diana Pasulka Michael Combs Heroine of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda 20 Sarah E. Bode Kathryn Bateman Dr. Alex Porco Lauren B. Evans Alignment and Argument: Karen Head Dr. Michelle Scatton-Tessier Shanon Gentry Active Heroines: When a Heroine is Both Responds to Poems by Dickey and Chappell Amy Schlag Katja Huru Real and Symbolic 27 74 Erin Sroka Jamie Joyner Rachel Jo Smyer Brian Caskey Dr. -

The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens

dining in the sanctuary of demeter and kore 1 Hesperia The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens Volume 78 2009 This article is © The American School of Classical Studies at Athens and was originally published in Hesperia 78 (2009), pp. 269–305. This offprint is supplied for personal, non-commercial use only. The definitive electronic version of the article can be found at <http://dx.doi.org/10.2972/hesp.78.2.269>. hesperia Tracey Cullen, Editor Editorial Advisory Board Carla M. Antonaccio, Duke University Angelos Chaniotis, Oxford University Jack L. Davis, American School of Classical Studies at Athens A. A. Donohue, Bryn Mawr College Jan Driessen, Université Catholique de Louvain Marian H. Feldman, University of California, Berkeley Gloria Ferrari Pinney, Harvard University Sherry C. Fox, American School of Classical Studies at Athens Thomas W. Gallant, University of California, San Diego Sharon E. J. Gerstel, University of California, Los Angeles Guy M. Hedreen, Williams College Carol C. Mattusch, George Mason University Alexander Mazarakis Ainian, University of Thessaly at Volos Lisa C. Nevett, University of Michigan Josiah Ober, Stanford University John K. Papadopoulos, University of California, Los Angeles Jeremy B. Rutter, Dartmouth College A. J. S. Spawforth, Newcastle University Monika Trümper, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Hesperia is published quarterly by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Founded in 1932 to publish the work of the American School, the jour- nal now welcomes submissions from all scholars working in the fields of Greek archaeology, art, epigraphy, history, materials science, ethnography, and literature, from earliest prehistoric times onward. -

Sweat: the Exodus from Physical and Mental Enslavement to Emotional and Spiritual Liberation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation Aqueelah Roberson University of Central Florida Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Roberson, Aqueelah, "Sweat: The Exodus From Physical And Mental Enslavement To Emotional And Spiritual Liberation" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3319. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3319 SWEAT: THE EXODUS FROM PHYSICAL AND MENTAL ENSLAVEMENT TO EMOTIONAL AND SPIRITUAL LIBERATION by AQUEELAH KHALILAH ROBERSON B.A., North Carolina Central University, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of Theatre in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2007 © 2007 Aqueelah Khalilah Roberson ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to showcase the importance of God-inspired Theatre and to manifest the transformative effects of living in accordance to the Word of God. In order to share my vision for theatre such as this, I will examine the biblical elements in Zora Neale Hurston’s short story Sweat (1926). I will write a stage adaptation of the story, while placing emphasis on the biblical lessons that can be used for God-inspired Theatre. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

YLO89 Magazine

•YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 1 TRD COVER Youth Leaders Only / Music Resource Book / Volume 91 / Spring 2013 Cover: Red 25 Ways To Create A Crisis Page 6 When Volunteers Date Kids Page 8 The Crisis Head/Heart Disconnect Page 10 INSIDE: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Music-Media Grad Gift Page 18 Heart of the Artist: RED Page 15 Jeremy Camp Page 16 The American Bible Challenge: Jeff Foxworthy Interview Page 12 Worship Chord Charts from Gungor, Planetshakers, Elevation Worship, Everfound Page 42 y r t s i & n i c i M s u h t M u o g Y n i n z i i a m i i x d a e M M CRISIS: ® HANDLING THOSE “UH OH!” SITUATIONS •YLO 91_Layout 1 2/13/13 3:02 PM Page 2 >> TRD TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS MAIN/MILD/HOT ARE LISTED ALPHABETICALLY BY ARTIST 6 8 10 11 FEATURE 25 Ways To Create When Volunteers The Crisis I’m In A ARTICLES: Your Own Crisis Date Kids Disconnect Crisis NOW MAIN: 18 20 25 CONGRADULATIONS! PURPOSE FILM Artist: CLASS OF 2013 DVD GUNGOR Album Title: ConGRADulations! Class of 2013 Purpose A Creation Liturgy (Live) Song Title: Unstoppable Beautiful Things Study Theme: Sacrifice Life; Purpose Meaning Renewal MILD: 21 22 23 ELEVATION Artist: CAPITAL KINGS WORSHIP EVERFOUND Album Title: Capital Kings Nothing Is Wasted Everfound Song Title: You’ll Never Be Alone Nothing Is Wasted Never Beyond Repair Study Theme: God’s Presence Difficulty; Hope Within Grace HOT: 24 26 28 Artist: FLYLEAF JEKOB JSON Album Title: New Horizons Faith Hope Love Growing Pains Song Title: New Horizons Love Is All Brand New Study Theme: Hope; In God Love; Unconditional -

Jonah's Gourd Vine and South Moon Under As New Southern Pastoral

Re-Visioning Nature: Jonah’s Gourd Vine and South Moon Under as New Southern Pastoral Kyoko Shoji Hearn Introduction Despite their well-known personal correspondence, few critical studies read the works of two Southern women writers, Zora Neale Hurston and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings together. Both of them began to thrive in their literary career after they moved to Florida and published their first novels, Jonah’s Gourd Vine (1934) and South Moon Under (1933). When they came down to central Florida (Hurston, grown up in Eatonville, and coming back as an anthropological researcher, Rawlings as an owner of citrus grove property) in the late 1920s, the region had undergone significant social and economic changes. During the 1920s, Florida saw massive influx of people from varying social strata against the backdrop of the unprecedented land boom, the expansion of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, the statewide growth of tourism, and the development of agriculture including the citrus industry in central Florida.1 Hurston’s and Rawlings’s relocation was a part of this mobility. Rawlings’s first visit to Florida occurred in March 1928, when she and her husband Charles had a vacation trip. Immediately attracted by the region’s charm, the couple migrated from Rochester, New York, to be a part of booming citrus industry.2 Hurston was aware of the population shift taking place in her home state and took it up in her work. At the opening of Mules and Men (1935), she writes: “Dr. Boas asked me where I wanted to work and I said, ‘Florida,’ and gave, as my big reason, that ‘Florida is a place that draws people—white people from all over the world, and Negroes from every Southern state surely and some from the North and West.’ So I knew that it was possible for me to get a cross section of the Negro South in the one state” (9). -

Chaotic Descriptor Table

Castle Oldskull Supplement CDT1: Chaotic Descriptor Table These ideas would require a few hours’ the players back to the temple of the more development to become truly useful, serpent people, I decide that she has some but I like the direction that things are going backstory. She’s an old jester-bard so I’d probably run with it. Maybe I’d even treasure hunter who got to the island by redesign dungeon level 4 to feature some magical means. This is simply because old gnome vaults and some deep gnome she’s so far from land and trade routes that lore too. I might even tie the whole it’s hard to justify any other reason for her situation to the gnome caves of C. S. Lewis, to be marooned here. She was captured by or the Nome King from L. Frank Baum’s the serpent people, who treated her as Ozma of Oz. Who knows? chattel, but she barely escaped. She’s delirious, trying to keep herself fed while she struggles to remember the command Example #13: word for her magical carpet. Malamhin of the Smooth Brow has some NPC in the Wilderness magical treasures, including a carpet of flying, a sword, some protection from serpents thingies (scrolls, amulets?) and a The PCs land on a deadly magical island of few other cool things. Talking to the PCs the serpent people, which they were meant and seeing their map will slowly bring her to explore years ago and the GM promptly back to her senses … and she wants forgot about it. -

University of Alberta Alice Walker: a Litemy Genealogist by Paege

University of Alberta Alice Walker: A Litemy Genealogist by Paege Alessandra Moore A thesis submitted to the Facdty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirernents of the degree of Master of Arîs Department of English Edmonton, Alberta Fa11 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationaIe ofCanada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OctawaON KtAON4 OttawaON KIAON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libmy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distniiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Keep in mind always the present you are constmcting. It should be the hture you want. -01% The Temple of My Familiar by Nice Waker This dissertation is dedicated to Sputnik who insisted 1 remain at my desk. Table of Contents Introduction ........................ ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 : Alice Waikefs Creative and Literary Geneaiogy ........................................... 3 Chapter 2: Their Eyes Were Watching God and The Color Purple ................................. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

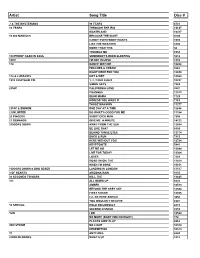

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing.