Social Class and the Written and Unwritten Rules of Competitive College Admissions: a Comparative Study of International Baccalaureate Schools in Ecuador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Ethnic Boundaries

Changing Ethnic Boundaries: Politics and Identity in Bolivia, 2000–2010 Submitted by Anaïd Flesken to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ethno–Political Studies in October 2012 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other university. Signature: …………………………………………………………. Abstract The politicization of ethnic diversity has long been regarded as perilous to ethnic peace and national unity, its detrimental impact memorably illustrated in Northern Ireland, former Yugo- slavia or Rwanda. The process of indigenous mobilization followed by regional mobilizations in Bolivia over the past decade has hence been seen with some concern by observers in policy and academia alike. Yet these assessments are based on assumptions as to the nature of the causal mechanisms between politicization and ethnic tensions; few studies have examined them di- rectly. This thesis systematically analyzes the impact of ethnic mobilizations in Bolivia: to what extent did they affect ethnic identification, ethnic relations, and national unity? I answer this question through a time-series analysis of indigenous and regional identification in political discourse and citizens’ attitudes in Bolivia and its department of Santa Cruz from 2000 to 2010. Bringing together literature on ethnicity from across the social sciences, my thesis first develops a framework for the analysis of ethnic change, arguing that changes in the attributes, meanings, and actions associated with an ethnic category need to be analyzed separately, as do changes in dynamics within an in-group and towards an out-group and supra-group, the nation. -

Costanera Center

SKIDATA Installations Shopping Centers Chile Costanera Center The Costanera Center is located in the up-and-coming business district of Santiago - unofficially known as “Sanhattan”. The complex, covering an area of 700,000 2m , includes the tallest skyscraper in Latin America, the “Gran Torre Santiago”, which is 300 meters high and has 64 floors, as well as the largest shopping center in the region with 300 stores, restaurants, a large cinema and a huge, high-quality supermarket. Every month, hundreds of thousands of visitors are welcomed to the center. After six years of construction, the Costanera Center finally opened its doors in 2012. The 5,700 available parking spaces, of which 3,500 are in the parking garages, are frequented by 12,000 vehicles daily. Additional parking facilities are currently in planning to meet the needs of hotel guests and the numerous companies which are moving into new offices in the “Gran Torre Santiago”. www.skidata.com Costanera Center Shopping Centers Chile Project description The owner and operator, Cencosud, was looking on which of the thousands of parking spaces his for an ultra-modern and reliable solution with a car is parked, he only needs to use one of the special focus on both design and functionality. SKIDATA automated pay stations. After reading Especially important was the ability to adapt the customer’s parking ticket, the system then to the current and future demands of the searches for the vehicle using its cameras. dynamic retail sector, particularly in light of the huge increase in the number of visitors For its regular customers, Cencosud offers a at peak shopping periods throughout the post-payment customer card (RFID-based), year, such as Christmas and Valentine’s Day. -

Nationalism and Ethnic Politics Book Reviews

This article was downloaded by: [University College London] On: 29 December 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 772858957] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Nationalism and Ethnic Politics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636289 Book reviews To cite this Article (2003) 'Book reviews', Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 9: 2, 128 — 148 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13537110412331301445 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13537110412331301445 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 92nep06.qxd 27/10/2003 09:21 Page 128 Book Reviews rank K. Salter (ed.). Risky Transactions: Trust, Kinship and Ethnicity. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2002. -

States of Extraction: the Emergence and Effects of Indigenous Autonomy

States of Extraction: The Emergence and Effects of Indigenous Autonomy in the Americas by Christopher L. Carter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Thad Dunning, Chair Professor Ruth Collier Assistant Professor Andrew Little Associate Professor Alison Post Professor Noam Yuchtman Summer 2020 States of Extraction: The Emergence and Effects of Indigenous Autonomy in the Americas Copyright 2020 by Christopher L. Carter 1 Abstract States of Extraction: The Emergence and Effects of Indigenous Autonomy in the Americas By Christopher L. Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Thad Dunning, Chair From the arrival of the first European settlers, indigenous groups in the Americas have experienced near-constant extraction of their land, labor, and capital, but they have also sometimes been offered greater autonomy over their local affairs. This dissertation explores the emergence and effects of indigenous autonomy. I investigate three central questions. Why do central states grant indigenous autonomy in some cases and not others? Why do native communities sometimes embrace government offers of autonomy and sometimes resist? And how does autonomy shape indigenous groups’ long-term access to political representation? To answer these questions, I develop a theory that emphasizes the central explanatory role of resource extraction by state and private actors. In a first section of the dissertation, I examine the decision by central states to grant indigenous autonomy. I argue that individual incumbents recognize autonomy when two conditions jointly obtain. -

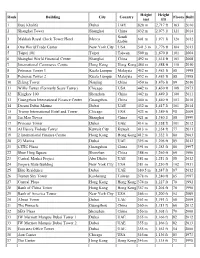

List of World's Tallest Buildings in the World

Height Height Rank Building City Country Floors Built (m) (ft) 1 Burj Khalifa Dubai UAE 828 m 2,717 ft 163 2010 2 Shanghai Tower Shanghai China 632 m 2,073 ft 121 2014 Saudi 3 Makkah Royal Clock Tower Hotel Mecca 601 m 1,971 ft 120 2012 Arabia 4 One World Trade Center New York City USA 541.3 m 1,776 ft 104 2013 5 Taipei 101 Taipei Taiwan 509 m 1,670 ft 101 2004 6 Shanghai World Financial Center Shanghai China 492 m 1,614 ft 101 2008 7 International Commerce Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 484 m 1,588 ft 118 2010 8 Petronas Tower 1 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 8 Petronas Tower 2 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia 452 m 1,483 ft 88 1998 10 Zifeng Tower Nanjing China 450 m 1,476 ft 89 2010 11 Willis Tower (Formerly Sears Tower) Chicago USA 442 m 1,450 ft 108 1973 12 Kingkey 100 Shenzhen China 442 m 1,449 ft 100 2011 13 Guangzhou International Finance Center Guangzhou China 440 m 1,440 ft 103 2010 14 Dream Dubai Marina Dubai UAE 432 m 1,417 ft 101 2014 15 Trump International Hotel and Tower Chicago USA 423 m 1,389 ft 98 2009 16 Jin Mao Tower Shanghai China 421 m 1,380 ft 88 1999 17 Princess Tower Dubai UAE 414 m 1,358 ft 101 2012 18 Al Hamra Firdous Tower Kuwait City Kuwait 413 m 1,354 ft 77 2011 19 2 International Finance Centre Hong Kong Hong Kong 412 m 1,352 ft 88 2003 20 23 Marina Dubai UAE 395 m 1,296 ft 89 2012 21 CITIC Plaza Guangzhou China 391 m 1,283 ft 80 1997 22 Shun Hing Square Shenzhen China 384 m 1,260 ft 69 1996 23 Central Market Project Abu Dhabi UAE 381 m 1,251 ft 88 2012 24 Empire State Building New York City USA 381 m 1,250 -

New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain • Carsten Jacob Humlebæk and Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain

New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain in Nationalism on Perspectives New • Carsten Humlebæk Jacob and Antonia María Jiménez Ruiz New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain Edited by Carsten Jacob Humlebæk and Antonia María Ruiz Jiménez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Genealogy www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain New Perspectives on Nationalism in Spain Editors Carsten Humlebæk Antonia Mar´ıaRuiz Jim´enez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editors Carsten Humlebæk Antonia Mar´ıa Ruiz Jimenez´ Copenhagen Business School Universidad Pablo de Olavide Denmark Spain Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Genealogy (ISSN 2313-5778) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/genealogy/special issues/perspective). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03943-082-6 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03943-083-3 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador

Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador By David Heath Cooper Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Mehrangiz Najafizadeh ________________________________ Dr. Robert Antonio ________________________________ Dr. Ebenezer Obadare Date Defended: April 18th, 2014 The Thesis Committee for David Heath Cooper certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Redefining the State Plurinationalism and Indigenous Resistance in Ecuador ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Mehrangiz Najafizadeh Date approved: April 18th, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Since the 1990s, the Ecuadorian Indigenous movement has transformed the nation's political landscape. CONAIE, a nationwide pan-Indigenous organization, and its demands for plurinationalism have been at the forefront of this process. For CONAIE, the demand for a plurinational refounding of the state is meant as both as a critique of and an alternative to what the movement perceives to be an exclusionary and Eurocentric nation-state apparatus. In this paper, my focus is twofold. I first focus on the role of CONAIE as the central actor in organizing and mobilizing the groundswell of Indigenous activism in Ecuador. After an analysis of the historical roots of the movement, I trace the evolution of CONAIE from its rise in the 1990s, through a period of decline and fragmentation in the early 2000s, and toward possible signs of resurgence since 2006. In doing so, my hope is to provide a backdrop from which to better make sense both of CONAIE's plurinational project and of the implications of the 2008 constitutional recognition of Ecuador as a plurinational state. -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Constitutions Assessment Tool Amanda Cats-Baril © 2020 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <https://www.idea.int> The electronic version of this publication, except the images, is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non- commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic and cover design: Richard van Rooijen (based on a concept developed by KSB Design) Cover image and artwork: Ancestors © Sarrita King Sarrita’s Ancestors paintings are layered with dots. Markings made on the land over thousands of years can be seen entangled with patterns covering the land today, such as sand hills, flora and paths made by humans and animals. Beneath the land are the waterways which have been virtually constant over time feeding the land, the flora, fauna and humans. These are the same waterways that supplied our ancestors which are now one with the land. -

Explorer Santiago | Chile | July 2020

Explorer Santiago | Chile | July 2020 ¡Viva Chile! Before the global pandemic put pay to non-essential international travel, we visited Chile’s capital city to explore Santiago for our latest global retail travelogue. Santiago fuses the influences of all that have settled there over the years. With a strong Spanish and Mediterranean vibe, its business connections with America, and the rest of Latin America are everywhere. The effect is a vibrant and colourful backdrop that’s full of spirit and dynamism. Santiago retail is characterised by diversity, quality and originality—at all ends of the market—with an impressive array of both local and famous international brand names. Opened in 2013, the 62-storey tall skyscraper that is Gran Torre Santiago plays host to the largest shopping mall in Latin America—one of Santiago’s many outstanding retail destinations. Dynamic and cosmopolitan, it is a vibrant city that is bursting with opportunities for retail adventure. By Karl McKeever Founder & Managing Director visualthinking.co.uk Downtown Avenida Andrés Bello 2425, Providencia Its remote location means that Chilean retailers are quick to look outward. With exciting concepts, new ideas and embracing new thinking to help them prosper, they are open and creative. In this issue, we select some of the exciting names and places that are making their mark—revolutionising retail in a way that only the country’s unique pioneering spirit and talented retail people can. In Explorer: Chile, we celebrate all that is good in retail in this stunning Latin American city. Like a fine wine, Santiago retailing is getting better with age. -

Rethinking Indigenous Autonomism in Latin America

Rethinking Indigenous Autonomism in Latin America Author Gaitan-Barrera, Alejandra Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2784 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366022 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Rethinking Indigenous Autonomism in Latin America By Alejandra Gaitán-Barrera Master of Arts (International Relations) Bachelor of Arts (International Relations) School of Government and International Relations Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Abstract This thesis contributes to a broader scholarly understanding of how indigenous movements in Latin America articulate autonomy. One of the central objectives of this research is to address a simple, yet often either assumed or unheeded, question: what does the indigenous subject want? What are the distinct meanings behind the political projects put forward by indigenous movements in the region? How do they envision their liberation from the current systems of oppression? And, most importantly, how do they define concepts such as “self-determination” and “autonomy”? These questions are central to understanding the nuanced transformative processes that indigenous peoples in Latin America have set into motion. In this sense, this thesis will demonstrate that far from homogenous, each movement, according to its own lived experiences of colonization and settlement, national building processes, local history, as well as cultural and political imaginaries and collective memories, conceives autonomy in a different way. Out of these distinct articulations of autonomy, this thesis argues there are two movements at the forefront of an unheeded and overlooked autonomist project: the Council of Miskitu Elders in Mosquitia (Nicaragua) and the Arauco-Malleco Coordinating Committee in Wallmapu (Chile). -

The National and Plurinational Community: Necessary

THE NATIONAL AND PLURINATIONAL COMMUNITY: NECESSARY AND IMPOSSIBLE An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by REBEKAH BURNHAM Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. Maddalena Cerrato May 2019 Major: International Studies Spanish TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review.............................................................................................................. 1 Thesis Statement .............................................................................................................. 2 Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................... 2 Project Description ........................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTERS I. COMMUNITYAS IT EXISTS ................................................................................... 5 Community: Creation............................................................................................ 5 II. COMMUNITY AS IT PERSISTS ........................................................................... -

Where Is the Empire State Building? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHERE IS THE EMPIRE STATE BUILDING? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Janet Pascal,Daniel Colon,David Groff | 112 pages | 31 Jul 2015 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448484266 | English | New York, United States Where Is the Empire State Building? PDF Book Monitor News Service. Office skyscraper in Manhattan, New York City. August 3, That is smoke and mirrors. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. Portraits of America. I researched this demon goddess. Live Science. History at your fingertips. The face of this demon Kali, has a belt of severed heads. The Empire State Building has been hailed as an example of a " wonder of the world " due to the massive effort expended during construction. The pair landed safely more than 1, feet below on 33rd Street, but while McCarthy was quickly arrested, Boyd simply hailed a cab and escaped. July 27, The company's president, Floyd De L. June 6, Morehouse, W. He draws those in who are looking for power. He had been laid off from his job in Retrieved August 30, Gran Torre Santiago. Empire State Building For Sale? William B. The placement of the stations in the Empire State Building became a major issue with the construction of the World Trade Center Twin Towers in the late s, and early s. The Empire State Building stood as the world's tallest building until the construction of the World Trade Center in ; following its collapse in , the Empire State Building was again the city's tallest skyscraper until The elevator plummeted from the 75th floor and soon crashed into the subbasement, but luckily for Oliver, more than a thousand feet of severed elevator cable had gathered at the bottom of the shaft, cushioning the blow.