Review of the Indian Army Doctrine: Dealing with Two Fronts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A CASE for CREATION of a JOINT TRAINING COMMAND (JTC) for the INDIAN DFENECE FORCES By

A CASE FOR CREATION OF A JOINT TRAINING COMMAND (JTC) FOR THE INDIAN DFENECE FORCES By Air Cmde T Chand (Retd) Training philosophy, infrastructure and capacity created by the Indian Defence Forces over a period of time is considered one of the best in the world. Officers and other trainees from the defence forces of many countries are also trained every year and there is spare capacity in many institutions to expand this scope. Many improvements have taken place for service specific and joint training issues and the scope and extent of the later has widened to the extent possible. There is a duplication of certain type of training institutions which many suggest can be curtailed for cost cutting but there is another view point which suggests that the sheer numbers to be trained call for more than one training institutions. The academic model of having so many affiliated colleges to one university, most of which follow same curriculum to accommodate the large number of students is quoted in support of non integration of some of the training facilities of the respective services. There are those who believe that a kind of equilibrium has already been achieved and any further disruptions will adversely affect the high 2 training standards achieved by the institutions of individual services. There is also news that “Joint training command for Army, Navy and IAF is in the works, Nagpur the likely base and this development has put Army plan to shift ARTRAC from Shimla to Meerut on hold for now1”. HQs IDS has streamlined the setup for mentoring and controlling the tri service training institutions besides developing doctrines and concepts for the three services. -

Battle of Hajipir (Indo-Pak War 1965)

No. 08/2019 AN INDIAN ARMY PUBLICATION August 2019 BATTLE OF HAJIPIR (INDO-PAK WAR 1965) MAJOR RANJIT SINGH DAYAL, PVSM, MVC akistan’s forcible attempt to annex Kashmir was defeated when India, even though surprised by the Pakistani offensive, responded with extraordinary zeal and turned the tide in a war, Pakistan thought it would win. Assuming discontent in Kashmir with India, Pakistan sent infiltrators to precipitate Pinsurgency against India under ‘OPERATION GIBRALTAR’, followed by the plan to capture Akhnoor under ‘OPERATION GRAND SLAM’. The Indian reaction was swift and concluded with the epic capture of the strategic Haji Pir Pass, located at a height of 2637 meters on the formidable PirPanjal Range, that divided the Kashmir Valley from Jammu. A company of 1 PARA led by Major (later Lieutenant General) Ranjit Singh Dayal wrested control of Haji Pir Pass in Jammu & Kashmir, which was under the Pakistani occupation. The initial victory came after a 37- hour pitched battle by the stubbornly brave and resilient troops. Major Dayal and his company accompanied by an Artillery officer started at 1400 hours on 27 August. As they descended into the valley, they were subjected to fire from the Western shoulder of the pass. There were minor skirmishes with the enemy, withdrawing from Sank. Towards the evening, torrential rains covered the mountain with thick mist. This made movement and direction keeping difficult. The men were exhausted after being in the thick of battle for almost two days. But Major Dayal urged them to move on. On reaching the base of the pass, he decided to leave the track and climb straight up to surprise the enemy. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Union Defence Services Air Force

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India for the year ended March 2015 Union Government (Defence Services) Air Force No. 18 of 2016 Report No. 18 of 2016 (Air Force) CONTENTS Paragraph Description Page Number Number Preface iii Overview v Glossary ix CHAPTER I: Introduction 1.1 Profile of the audited entities 1 1.2 Authority for audit 2 1.3 Audit methodology and procedure 2 1.4 Defence budget 3 1.5 Budget and expenditure of Indian Air Force 4 1.6 Response to Audit 9 1.7 Recoveries at the instance of Audit 10 CHAPTER-II: Audit of Air HQ Communication 15 Squadron (AHCS) CHAPTER-III: Audit Paragraphs relating to Contract Management 3.1 Acquisition and operation of C-17 Globemaster 25 III aircraft 3.2 Procurement of 14 additional Dornier aircraft 31 3.3 Refurbishment of ‘X’ system 33 CHAPTER-IV: Audit Paragraphs relating to Works Services 4.1 Excess provision of hangars resulting in 39 avoidable expenditure of `24.28 crore i Report No. 18 of 2016 (Air Force) 4.2 Irregularities in drafting tender resulting in 42 excess payment 4.3 Excess provision of 200 seats capacity in an 44 Auditorium 4.4 Avoidable creation of permanent assets at a cost 46 of `1.10 crore CHAPTER-V: Audit Paragraphs on other issues 5.1 In-effective usage of Access Control System 49 5.2 Irregular payment of Transport Allowance 52 5.3 Avoidable expenditure of `131.45 lakh due to 53 payment of Electricity tax 5.4 Avoidable expenditure of ```80.07 lakh on repair 56 of an aero engine ANNEX 59 to 64 Photographs : Courtesy IAF ii Report No. -

![Uzda]Rj SVU Z W` /$& SDUOH\V](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5045/uzda-rj-svu-z-w-sduoh-v-1205045.webp)

Uzda]Rj SVU Z W` /$& SDUOH\V

$ : # &) ; ) ; ; SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' )+,-).!/01 #*+,+#,- #./0 %*#.123 #> *@* *7C/11/157/ ,%+ >*1?* *5 57 0/1+ ? 15? 7?/*+@ @B*@ N 15+@E+ / * */*F1/ @/ @7@ /@ * @7/ A*@?B6A+ <5 '('$))* '=% < *# & !!2$2$3 !22 /*+*5 ith an aim to increase Wtransparency in alloca- tion of hospital beds during the /*+*5 Covid-19 pandemic, Lieutenant-Governor of Delhi day after the two Armies Q R Anil Baijal on Wednesday Amutually started pulling directed Chief Secretary Vijay back their troops from the Dev to ensure installation of stand-off sites on the Line of LED (Light Emitting Diode) Actual Control (LAC) in boards at all major health facil- Ladakh, senior commanders ities to display bed availability, 5*# 8 of India and Chine met on charges and details of persons Wednesday to fine-tune total to be contacted for admission. # disengagement. They also Earlier in the day, Delhi agreed to continue the dialogue. Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal In Beijing, the Chinese on Wednesday said his Government said on General-level talks on Government will implement # Wednesday, the two armies Wednesday at Chushul on the have started implementing the LAC, sources said some more # O “positive consensus” reached by rounds of such parleys will take the senior military officials of place over the next ten to 12 & the two countries on June 6. days. # This high-level meeting These regular interactions between Lt General Harinder ranging from Major Generals Singh and Major General Liu to Colonel level will ensure that Lin was aimed at “easing” the the ongoing confrontation !" # situation along the LAC. ends. The Chinese Foreign Moreover, the latest Major in the national Capital for In his letter, the L-G said the Covid-19 pandemic. -

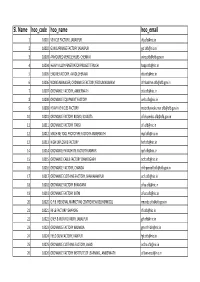

Sl. Name Hoo Code Hoo Name Hoo Email

Sl. Name hoo_code hoo_name hoo_email 1 10001 VEHICLE FACTORY, JABALPUR [email protected] 2 10002 GUN CARRIAGE FACTORY JABALPUR [email protected] 3 10003 ARMOURED VEHICLE HQRS. CHENNAI [email protected] 4 10004 HEAVY ALLOY PENETRATOR PROJECT TIRUCHI [email protected] 5 10005 ENGINE FACTORY, AVADI,CHENNAI [email protected] 6 10006 WORKS MANAGER, ORDNANCE FACTORY,YEDDUMAILARAM [email protected] 7 10007 ORDNANCE FACTORY, AMBERNATH [email protected] 8 10008 ORDNANCE EQUIPMENT FACTORY [email protected] 9 10009 HEAVY VEHICLES FACTORY [email protected] 10 10010 ORDNANCE FACTORY BOARD, KOLKATA [email protected] 11 10011 ORDNANCE FACTORY ITARSI [email protected] 12 10012 MACHINE TOOL PROTOTYPE FACTORY AMBERNATH [email protected] 13 10013 HIGH EXPLOSIVE FACTORY [email protected] 14 10014 ORDNANCE PARACHUTE FACTORY KANPUR [email protected] 15 10015 ORDNANCE CABLE FACTORY CHANDIGARH [email protected] 16 10016 ORDNANCE FACTORY, CHANDA [email protected] 17 10017 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, SHAHJAHANPUR [email protected] 18 10018 ORDNANCE FACTORY BHANDARA [email protected] 19 10019 ORDNANCE FACTORY KATNI [email protected] 20 10020 O.F.B. REGIONAL MARKETING CENTRE NEW DELHI(RMCDL) [email protected] 21 10021 RIFLE FACTORY ISHAPORE [email protected] 22 10022 GREY & IRON FOUNDRY, JABALPUR [email protected] 23 10023 ORDNANCE FACTORY NALANDA gm‐ofn‐[email protected] 24 10024 FIELD GUN FACTORY, KANPUR [email protected] 25 10025 ORDNANCE CLOTHING FACTORY, AVADI [email protected] 26 10026 ORDNANCE FACTORY INSTITUTE OF LEARNING , AMBERNATH ofilam‐[email protected] 27 10027 OFB, -

Indian Ministry of Defence Annual Report 2004

ANNUAL REPORT 2004-05 lR;eso t;rs Ministry of Defence Government of India Front Cover : BRAHMOS Supersonic Cruise Missile being launched from a Naval war ship. Back Cover: The aerobatic team of the Indian Air Force the Suryakirans demonstrating its awesome aerobatic skills. CONTENTS 1. The Security Environment 5 2. Organisation and Functions of the Ministry of Defence 17 3. Indian Army 25 4. Indian Navy 45 5. Indian Air Force 55 6. Coast Guard 61 7. Defence Production 69 8. Defence Research and Development 97 9. Inter-Service Organisations 115 10. Recruitment and training 131 11. Resettlement and welfare of ex-servicemen 159 12. Cooperation between the armed forces and civil authorities 177 13. National Cadet Corps 185 14. Defence Relations with Foreign Countries 197 15. Ceremonial, Academic and Adventure Activities 203 16. Activities of Vigilance Units 215 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 219 Appendix I. Matters Dealt by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 227 II. Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries 232 who were in Position from April 1, 2004 Onwards III. Summary of Latest Comptroller & Auditor General 233 (C&AG) Report on the Working of Ministry of Defence 1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Su-30 5 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT is bordered by the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. 1.1 Connected by land to west, India is thus a maritime as well as central, continental, and south-east continental entity. This geographical Asia, and by sea, to the littoral states and topographical diversity, espe- of the Indian Ocean from East Africa cially on its borders, also poses to the Indonesian archipelago, India unique challenges to our Armed is strategically located vis-à-vis both Forces. -

IAF Equipment and Force Structure Requirements to Meet External Threats, 2032

IAF Equipment and Force Structure Requirements to Meet External Threats, 2032 Vivek Kapur* In keeping with the theme ‘IAF Deep Multidimensional Change 2032: Imperatives and a Roadmap’, this article focuses on the responses to the external threat challenges that are likely to be face by IAF in 2032. These external challenges have been identified to be the individual Chinese and Pakistani threats as well as a combined Sino-Pak threat. The article confines itself to developing a possible force structure only in terms of numbers of combat and support aircraft of various types for 2032. It contains an examination of the currently planned IAF structure for the year 2022 and beyond, against the war-gamed force requirement for winning wars along our borders while retaining capability to project force in areas of national interest beyond our borders. The article underscores the fact that the current plan for the force structure requires to be enhanced to meet the challenges successfully. INTRODUCTION This article follows ‘Challenges for the Indian Air Force: 2032’ (Vol. 7, No. 1, January-March 2013), dealing with the main challenges Indian Air Force (IAF) is likely to face in 2032, when it completes a century. Here, I assess possible responses to the external challenges posed by the Peoples Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and Pakistan Air Force (PAF). I do so separately in a single-front war scenario against either one and follow it up with a worst case scenario of a simultaneous war against both. I begin * The author was a Research Fellow with the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. -

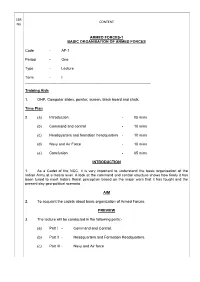

Ss 1.1 Basic Org of Armed Forces and Army

SER CONTENT No ARMED FORCES-1 BASIC ORGANISATION OF ARMED FORCES Code - AF-1 Period - One Type - Lecture Term - I _____________________________________________________________ Training Aids 1. OHP, Computer slides, pointer, screen, black board and chalk. Time Plan 2. (a) Introduction. - 05 mins (b) Command and control - 10 mins (c) Headquarters and formation headquarters - 10 mins (d) Navy and Air Force - 10 mins (e) Conclusion - 05 mins INTRODUCTION 1. As a Cadet of the NCC, it is very important to understand the basic organisation of the Indian Army at a macro level. A look at the command and control structure shows how finely it has been tuned to meet India’s threat perception based on the major wars that it has fought and the present day geo-political scenario. AIM 2. To acquaint the cadets about basic organization of Armed Forces. PREVIEW 3. The lecture will be conducted in the following parts:- (a) Part I - Command and Control. (b) Part II - Headquarters and Formation Headquarters. (c) Part III - Navy and Air force (a) PART I-COMMAND AND CONTROL 4. Command. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of all the Armed Forces of the Country. The Chief of Army Staff is the head of the Indian Army and is responsible for the command, training, operations and administration. He carries out these functions through Army Headquarters. (Army HQ) of the 1.1 million strong force. A number of Staff Officers assist him, such as Principle Staff Officers(PSOs),Head of Arms and Services, etc. A Vice Chief and two Deputy Chiefs of Army Staff handle coordination. -

Armed Forces Module - II Structure and Role of the Forces

Armed Forces Module - II Structure and Role of the Forces 4 Note ARMED FORCES The soldiers are faced with a variety of challenges including the difficult areas like icy glaciers, sandy deserts, mountainous jungles and the vast seas. They willingly face these challenges and are prepared to make any sacrifice for the Nation. The values of comradeship and brotherhood pervade all ranks of the army. The soldiers lay down their lives for the three Ns - Naam (name or honour), Namak (loyalty to the Nation) and Nishan (insignia or flag of the unit/regiment or Nation). They exhibit valour when fighting the enemy. There is no discrimination on the basis of caste, religion or any other aspect. This ensures team spirit and unity. They usually choose death over dishonour. The forthrightness, integrity and dignity forms the ethos of every soldier. In this lesson we shall learn about the different Commands of the Indian Army in greater detail as well as the Ethos of the armed forces. Before we look at the organisational structure we shall examine the ethos of the Indian Army. Objectives After studying this lesson, you will be able to: • explain the role and organisational structure of Indian Army; • describe the role and structure of Indian Navy and • explain the role and organisational structure of Air Force. 4.1 Role of the Indian Army The Indian Army mainly has the task to protect the territorial integrity of our country and safeguard its sovereignty from external aggression or internal disorder. The army also provides assistance to the civil administration in the event of a natural or manmade disaster. -

Indian Army November 1962, a Department of Through Secretary of State for India Defence Production Was Set up to and Governor General-In-Council

1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Vigil at Siachen 1 India remains fully committed to maintain peace and stability with its neighbours in the region and in the global context through effective diplomacy, backed by credible military deterrence. 1.1 India has taken suitable steps Iraq, the nuclear stalemate on the to meet the challenges and Korean Peninsula, and the opportunities arising out of its rapidly unsatisfactory situation regarding the changing security environment. proliferation activities of the past While our peace effort with Pakistan have made Indian planners take into has maintained strategic stability in account these unsavoury aspects. our west, developments in Nepal and The Indian Ocean Region has Bangladesh during the course of the assumed enormous importance year have caused concern, mainly in considering our energy the border regions with these requirements. The oil flow in this countries. A concerted diplomatic region is estimated at 15.5 million effort with the two governments has barrels per day through the Persian brought about a degree of Gulf, 10.3 million barrels per day understanding and India continues through the Malacca Straits and 3.3 to work together with all its million barrels per day through the neighbours in ensuring peace and Babel-Mandab (Gulf of Aden). This stability in our region. The global traffic raises security as well as situation has mirrored our regional environmental concerns. The position. Concerns regarding Ministry of Defence has contributed terrorism, including state sponsored to Indias overall reaction to these terrorism, proliferation of weapons of growing challenges by keeping its mass destruction, trafficking of armed forces at the highest levels of narcotics, small arms and human defence preparedness and the ability beings, and the increasing profile of to react with swift counter measures.