Ecclesiastes: the Philippians of the Old Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

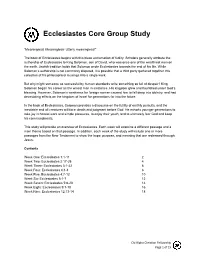

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

Ecclesiastes 1

International King James Version Old Testament 1 Ecclesiastes 1 ECCLESIASTES Chapter 1 before us. All is Vanity 11 There is kno remembrance of 1 ¶ The words of the Teacher, the former things, neither will there be son of David, aking in Jerusalem. any remembrance of things that are 2 bVanity of vanities, says the Teacher, to come with those that will come vanity of vanities. cAll is vanity. after. 3 dWhat profit does a man have in all his work that he does under the Wisdom is Vanity sun? 12 ¶ I the Teacher was king over Is- 4 One generation passes away and rael in Jerusalem. another generation comes, but ethe 13 And I gave my heart to seek and earth abides forever. lsearch out by wisdom concerning all 5 fThe sun also rises and the sun goes things that are done under heaven. down, and hastens to its place where This mburdensome task God has it rose. given to the sons of men by which to 6 gThe wind goes toward the south be busy. and turns around to the north. It 14 I have seen all the works that are whirls around continually, and the done under the sun. And behold, all wind returns again according to its is vanity and vexation of spirit. circuits. 15 nThat which is crooked cannot 7 hAll the rivers run into the sea, yet be made straight. And that which is the sea is not full. To the place from lacking cannot be counted. where the rivers come, there they re- 16 ¶ I communed with my own heart, turn again. -

Ecclesiastes 4:4-8 (

The Berean: Daily Verse and Commentary for Ecclesiastes 4:4-8 (http://www.theberean.org) Ecclesiastes 4:4-8 (4) Again, I saw that for all toil and every skillful work a man is envied by his neighbor. This also is vanity and grasping for the wind. (5) The fool folds his hands And consumes his own flesh. (6) Better a handful with quietness Than both hands full, together with toil and grasping for the wind. (7) Then I returned, and I saw vanity under the sun: (8) There is one alone, without companion: He has neither son nor brother. Yet there is no end to all his labors, Nor is his eye satisfied with riches. But he never asks, “ For whom do I toil and deprive myself of good?” This also is vanity and a grave misfortune. New King James Version Ecclesiastes 4:4-8 records Solomon's analysis of four types of workers. He appears to have disgustedly turned his attention from the corrupted halls of justice to the marketplace, watching and analyzing as people worked. Recall how those who work diligently are lauded throughout Proverbs and how Ecclesiastes 2 and 3 both extol work as a major gift of God. Solomon came away from this experience with assessments of four different kinds of workers. Understand that God chooses to illustrate His counsel by showing extremes; not everybody will fit one of them exactly. At the same time, we should be able to use the information to make necessary modifications to our approach to our own work. The first he simply labels the “skillful” worker. -

In Search of Kohelet

IN SEARCH OF KOHELET By Christopher P. Benton Ecclesiastes is simultaneously one of the most popular and one of the most misunderstood books of the Bible. Too often one hears its key verse, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity,” interpreted as simply an injunction against being a vain person. The common English translation of this verse (Ecclesiastes 1:2) comes directly from the Latin Vulgate, “Vanitas vanitatum, ominia vanitas.” However, the original Hebrew, “Havel havelim, hachol havel,” may be better translated as “Futility of futilities, all is futile.” Consequently, Ecclesiastes 1:2 is more a broad statement about the meaninglessness of life and actions that are in vain rather than personal vanity. In addition to the confusion that often surrounds the English translation of Ecclesiastes 1:2, the appellation for the protagonist in Ecclesiastes also loses much in the translation. In the enduring King James translation of the Bible, the speaker in Ecclesiastes is referred to as “the Preacher,” and in many other standard English translations of the Bible (Amplified Bible, New International Version, New Living Translation, American Standard Version) one finds the speaker referred to as either “the Preacher” or “the Teacher.” However, in the original Hebrew and in many translations by Jewish groups, the narrator is referred to simply as Kohelet. The word Kohelet is derived from the Hebrew root koof-hey-lamed meaning “to assemble,” and commentators suggest that this refers to either the act of assembling wisdom or to the act of meeting with an assembly in order to teach. Furthermore, in the Hebrew, Kohelet is generally used as a name, but in Ecclesiastes 12:8 it is also written as HaKohelet (the Kohelet) which is more suggestive of a title. -

Download Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament

Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament JESOT is published bi-annually online at www.jesot.org and in print by Wipf and Stock Publishers. 199 West 8th Avenue, Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401, USA ISBN 978-1-7252-6256-0 © 2020 by Wipf and Stock Publishers JESOT is an international, peer-reviewed journal devoted to the academic and evangelical study of the Old Testament. The journal seeks to publish current academic research in the areas of ancient Near Eastern backgrounds, Dead Sea Scrolls, Rabbinics, Linguistics, Septuagint, Research Methodology, Literary Analysis, Exegesis, Text Criticism, and Theology as they pertain only to the Old Testament. The journal seeks to provide a venue for high-level scholarship on the Old Testament from an evangelical standpoint. The journal is not affiliated with any particular academic institution, and with an international editorial board, online format, and multi-language submissions, JESOT seeks to cultivate Old Testament scholarship in the evangelical global community. JESOT is indexed in Old Testament Abstracts, Christian Periodical Index, The Ancient World Online (AWOL), and EBSCO databases Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament Executive Editor Journal correspondence and manuscript STEPHEN J. ANDREWS submissions should be directed to (Midwestern Baptist Theological [email protected]. Instructions for Seminary, USA) authors can be found at https://wipfandstock. com/catalog/journal/view/id/7/. Editor Books for review and review correspondence RUSSELL L. MEEK (Ohio Theological Institute, USA) should be directed to Andrew King at [email protected]. Book Review Editor All ordering and subscription inquiries ANDREW M. KING should be sent to [email protected]. -

Stronger Together (2017) Being the Church | Ecclesiastes 4:9-12 Southern Hills Baptist Church June 25, 2017

Stronger Together (2017) Being the Church | Ecclesiastes 4:9-12 Southern Hills Baptist Church June 25, 2017 WELCOME Happy Sunday to you. I’m glad to be sharing time together in God’s Word. We will be in Ecclesiastes 4 this morning so please turn in that direction if you have your Bibles with you. If you don’t, there should be a copy of God’s Word in one of the seats near you. INTRODUCTION – The Story that “Brought Being the Church” Let me briefly remind you why we are in the study that we are in currently. Back in January we got a call that was both unexpected and a future blessing, when the pastor of the church we were renting space from called to inform us that their lease was not getting renewed as the business next door was expanding. The landlord had agreed to give that growing business the space that we rented from New Life. We were told that we would have to be out of the building within 3 months. Worry Amidst Uncertainty This of course caused some worry within the hearts of your pastors. 3 months isn’t much time to make such a massive transition where we would have to make big decisions. One of the things that worried us most was how all of this change, uncertainty, and transition would affect the church. What we didn’t want was to see people lose sight of what was really important and who we really are as a people. • Were we going to be homeless for a while? Yes. -

Don't Freak Out, but YOU Are Not in Control Ecclesiastes 3:1-4:3 What's

Don’t freak out, but YOU are not in control Ecclesiastes 3:1-4:3 What’s the Point!?! Sermon 05 Out of the night that covers me, Black as the Pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul. In the fell clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud. Under the bludgeonings of chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade, And yet the menace of the years Finds, and shall find, me unafraid. It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll. I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul. That short Victorian poem, Invictus, was written by English poet, William Ernest Henley in 1875. When he was 14, Henley contracted a bone disease. A few years later, the disease had progressed to his foot. His doctor told him that the only way they could save his life was to amputate his leg just below the knee. So at 17 years of age, he half of his leg was amputated. While recovering from surgery, he wrote Invictus. “I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.” But he wasn’t, though he apparently had a full life, at age 53, William Ernest Henley died. Are you a control freak? Do you like to be in control? We humans love to be in control, to be the “masters of our fate: captains of our souls.” Ladies, does it drive you nuts when someone else works in your kitchen and moves things around? Are you that way at work? You have things just so in your workspace. -

We're in This Together

from the desk of . #626 Rande Wayne Smith 21 September 2014 D.Min., Th.M., M.Div. We’re In This Together - 1 WE NEED EACH OTHER Ecclesiastes 4:9-12 How many of you watched the Bears play last Sunday evening? … Great game! They can win when they play as a team. Okay, transition … God intends life to be a team sport. God has designed us to thrive in relationship, in community, in connection with other people, to be a team. st We go to the very 1 chapter of the Bible, & we discover that we’ve been made in God’s image. (Genesis 1:26- 27) And one aspect of His image is relational. Our God is a 3-in-1 God. He is Father, Son, & Holy Spirit. And so when God creates us in His image, He made us with a relational capacity, with a desire to be on the “team.” This morning we’re starting a 2-week series entitled, “We’re In This Together.” And my goal is to motivate you & equip you to build strong spiritual relationships with other people. And with that in mind, we begin this morning by seeing the benefit of doing life together. And we’re going to look at a passage from Ecclesiastes as the basis for today’s message. 2 So, listen now to Good News as recorded by Solomon, to you who have gathered here at Community Church. Within your hearing now comes the Word of the Lord … Two are better off than one, because together they can work more effectively. -

Survey of the Old Testament Instructor's Guide

Village Missions Website: http://www.vmcdi.com Contenders Discipleship Initiative E-mail: [email protected] Old Testament Village Missions The Hebrew Scriptures Contenders Discipleship Initiative The Law The Prophets The Writings Survey of the Old Testament Instructor’s Guide Contenders Discipleship Initiative – Old Testament Survey Instructor’s Guide TRAINING MODULE SUMMARY Course Name Survey of the Old Testament Course Number in Series 4 Creation Date March 2017 Created By: Cliff Horr Last Date Modified April 2018 Version Number 3.0 Copyright Note Contenders Discipleship Initiative is a two-year ministry equipping program started in 1995 by Pastor Ron Sallee at Machias Community Church, Snohomish, WA. More information regarding the full Contenders program and copies of this guide and corresponding videos can be found at http://www.vmcontenders.org or http://www.vmcdi.com Copyright is retained by Village Missions with all rights reserved to protect the integrity of this material and the Village Missions Contenders Discipleship Initiative. Contenders Discipleship Initiative Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in the Contenders Discipleship Initiative courses are those of the instructors and authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Village Missions. The viewpoints of Village Missions may be found at https://villagemissions.org/doctrinal-statement/ The Contenders program is provided free of charge and it is expected that those who receive freely will in turn give freely. Permission for non-commercial use -

Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ Ot Ha-ʻitim Li-Yeshurun Be-ʾerets Yisŕ Aʾel

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Miscellaneous Papers Miscellaneous Papers 8-2011 Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel David G. Cook Sol P. Cohen Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Cook, David G. and Cohen, Sol P., "Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel" (2011). Miscellaneous Papers. 10. https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 This is an English translation of Sefer Korot Ha-'Itim (First Edition, 1839; Reprint with Critical Introduction, 1975) This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel Abstract This work was authored by Menahem Mendel me-Kaminitz (an ancestor of one of the current translators David Cook) following his first attempt ot settle in the Land of Israel in 1834. Keywords Land of Israel, Ottoman Palestine, Menahem Mendel me-Kaminitz, Korat ha-'itim, history memoirs Disciplines Islamic World and Near East History | Jewish Studies | Religion Comments This is an English translation of Sefer Korot Ha-'Itim (First Edition, 1839; Reprint with Critical Introduction, 1975) This other is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 The Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel Sefer KOROT HA-‘ITIM li-Yeshurun be-Eretz Yisra’el by Menahem Mendel ben Aharon of Kamenitz Translation by: David G. -

Ecclesiastes Illustrations-Today in the Word

Ecclesiastes Illustrations-Today in the Word Ecclesiastes 1 For excellent daily devotionals bookmark Today in the Word. Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 TODAY IN THE WORD In his book Leap Over a Wall: Earthy Spirituality for Everyday Christians, author Eugene Peterson writes of the spirituality of work. He points out that as important as sanctuary is for our spiritual life, it isn't the primary context that God uses for our day-to-day spiritual development. “Work,” Peterson observes, “is the primary context for our spirituality.” This may come as a shock to some of us. Many believers have asked the question raised in Eccl 1:3 of today's reading: “What does man gain from all his labor at which he toils under the sun?” Thankfully, the answer is found throughout the Scriptures. Men and women were created to work because they were created in God's image and God is a worker. The wonders of creation are called the “works” of His hand (Ps. 8:6). That's not all—according to Jesus, God continues to work “to this very day” (John 5:17). Clearly, work itself is not a consequence of sin, since we find God Himself embracing work. Jesus, too, was no stranger to the world of work. Prior to beginning His public ministry, the Savior submitted Himself to the daily grind. Jesus did not merely dabble in work—He became so proficient in the vocation of His earthly father Joseph that others knew Him as a carpenter long before they knew Him as a rabbi (Mark 6:3).