Steve Biko, the Politics of Self-Writing and the Apparatus of Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malibongwe Let Us Praise the Women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn

Malibongwe Let us praise the women Portraits by Gisele Wulfsohn In 1990, inspired by major political changes in our country, I decided to embark on a long-term photographic project – black and white portraits of some of the South African women who had contributed to this process. In a country previously dominated by men in power, it seemed to me that the tireless dedication and hard work of our mothers, grandmothers, sisters and daughters needed to be highlighted. I did not only want to include more visible women, but also those who silently worked so hard to make it possible for change to happen. Due to lack of funding and time constraints, including raising my twin boys and more recently being diagnosed with cancer, the portraits have been taken intermittently. Many of the women photographed in exile have now returned to South Africa and a few have passed on. While the project is not yet complete, this selection of mainly high profile women represents a history and inspiration to us all. These were not only tireless activists, but daughters, mothers, wives and friends. Gisele Wulfsohn 2006 ADELAIDE TAMBO 1929 – 2007 Adelaide Frances Tsukudu was born in 1929. She was 10 years old when she had her first brush with apartheid and politics. A police officer in Top Location in Vereenigng had been killed. Adelaide’s 82-year-old grandfather was amongst those arrested. As the men were led to the town square, the old man collapsed. Adelaide sat with him until he came round and witnessed the young policeman calling her beloved grandfather “boy”. -

The History of Southern Africa Kim Worthington

Princeton University Department of History HST 468 - Senior Seminar: The History of Southern Africa Kim Worthington Wednesdays 9-12 Aaron Burr Hall - Room 213 Contact Information Email: [email protected] Office: Dickinson Hall, Room 101 Office Hours: Thursday 2:00-4:00 (or by appointment through WASS) Course Description This course aims to equip students with an understanding of the history of Southern Africa, focusing in particular on South Africa from the 18th to the 20th century. Southern Africa is a large and diverse region, with a rich and complex history dating back to the cradle of civilization. We will therefore only be looking at certain key moments and events. We will consider how the history of the region has been written, and from whose perspective. The course will touch on a range of issues, from settlement and displacement, slavery, colonialism, and projects of empire, to institutionalized racism, industrialization and its implications for communities, workers, and migration, State control of people and movement, local political activism in a continental and global context, urbanization, and other topics. A key learning outcome will be to develop an understanding of historiographical debates: Who writes history? In what context? To what are historians responding? What are a scholar’s aims, and what earlier historical understanding does s/he engage? Does s/he support or challenge accepted interpretations of the past? Students are not expected to have an in-depth grasp of any particular debates, but more to gain insight into how understandings of history and the events and people historical writings describe change over time. -

The Black Sash

THE BLACK SASH THE BLACK SASH MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 CONTENTS: Minutes Appendix Appendix 4. Appendix A - Register B - Resolutions, Statements and Proposals C - Miscellaneous issued by the National Executive 5 Long Street Mowbray 7700 MINUTES OF THE BLACK SASH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 - GRAHAMSTOWN SESSION 1: FRIDAY 2 MARCH 1990 14:00 - 16:00 (ROSEMARY VAN WYK SMITH IN THE CHAIR) I. The National President, Mary Burton, welcomed everyone present. 1.2 The Dedication was read by Val Letcher of Albany 1.3 Rosemary van wyk Smith, a National Vice President, took the chair and called upon the conference to observe a minute's silence in memory of all those who have died in police custody and in detention. She also asked the conference to remember Moira Henderson and Netty Davidoff, who were among the first members of the Black Sash and who had both died during 1989. 1.4 Rosemary van wyk Smith welcomed everyone to Grahamstown and expressed the conference's regrets that Ann Colvin and Jillian Nicholson were unable to be present because of illness and that Audrey Coleman was unable to come. All members of conference were asked to introduce themselves and a roll call was held. (See Appendix A - Register for attendance list.) 1.5 Messages had been received from Errol Moorcroft, Jean Sinclair, Ann Burroughs and Zilla Herries-Baird. Messages of greetings were sent to Jean Sinclair, Ray and Jack Simons who would be returning to Cape Town from exile that weekend. A message of support to the family of Anton Lubowski was approved for dispatch in the light of the allegations of the Minister of Defence made under the shelter of parliamentary privilege. -

Anc Today Voice of the African National Congress

ANC TODAY VOICE OF THE AFRICAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14 – 20 May 2021 Conversations with the President South Africa waging a struggle that puts global solidarity to the test n By President Cyril Ramaphosa WENTY years ago, South In response, representatives of massive opposition by govern- Africa was the site of vic- the pharmaceutical industry sued ment and civil society. tory in a lawsuit that pitted our government, arguing that such public good against private a move violated the Trade-Relat- As a country, we stood on princi- Tprofit. ed Aspects of Intellectual Property ple, arguing that access to life-sav- Rights (TRIPS). This is a compre- ing medication was fundamental- At the time, we were in the grip hensive multilateral agreement on ly a matter of human rights. The of the HIV/Aids pandemic, and intellectual property. case affirmed the power of trans- sought to enforce a law allowing national social solidarity. Sev- us to import and manufacture The case, dubbed ‘Big Pharma eral developing countries soon affordable generic antiretroviral vs Mandela’, drew widespread followed our lead. This included medication to treat people with international attention. The law- implementing an interpretation of HIV and save lives. suit was dropped in 2001 after the World Trade Organization’s Closing remarks by We are embracing Dear Mr President ANC President to the the future! Beware of the 12 NEC meeting wedge-driver: 4 10 Unite for Duma Nokwe 2 ANC Today CONVERSATIONS WITH THE PRESIDENT (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Re- ernment announced its support should be viewed as a global pub- lated Aspects of Intellectual Prop- for the proposal, which will give lic good. -

Botho/Ubuntu : Perspectives of Black Consciousness and Black Theology Ramathate TH Dolam University of South Africa, South Afri

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Botho/Ubuntu : Perspectives of Black Consciousness and Black Theology Ramathate TH Dolam University of South Africa, South Africa 0415 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract Botho/ubuntu is a philosophy that is as old as humanity itself. In South Africa, it was a philosophy and a way of life of blacks. It was an African cultural trait that rallied individuals to become communal in outlook and thereby to look out for each other. Although botho or ubuntu concept became popularised only after the dawn of democracy in South Africa, the concept itself has been lived out by Africans for over a millennia. Colonialism, slavery and apartheid introduced materialism and individualism that denigrated the black identity and dignity. The Black Consciousness philosophy and Black Theology worked hand in hand since the middle of the nine- teen sixties to restore the human dignity of black people in South Africa. Key words: Botho/Ubuntu, Black Consciousness, Black Theology, religion, culture. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org 532 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan 1. INTRODUCTION The contributions of Black Consciousness (BC) and Black Theology (BT) in the promotion and protection of botho/ubuntu values and principles are discussed in this article. The arrival of white people in South Africa has resulted in black people being subjected to historical injustices, cultural domination, religious vilification et cetera. BC and BT played an important role in identifying and analysing the problems that plagued blacks as a group in South Africa among the youth of the nineteen sixties that resulted in the unbanning of political organisations, release of political prisoners, the return of exiles and ultimately the inception of democracy. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

26 N. Barney Pityana

26 STEVE BIKO: PHILOSOPHER OF BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS N. Barney Pityana Let a new earth arise . Let another world be born . Let a bloody peace be written in the sky . Let a second generation full of courage issue forth, Let a people loving freedom come to growth, Let a beauty full of healing and a strength of final clenching be the pulsing in our spirits and our blood . Let the martial songs be written, Let the dirges disappear . Let a race of men rise and take control . – MARGARET WALKER, “FOR MY PEOPLE” I HAVE INTRODUCED THIS CHAPTER with an extract from Margaret Walker’s poem “For My People” .1 It is a verse from the African-American experience of slavery and dehumanisation . The poem was first published in 1942, and could be viewed as a precursor to the civil rights movement . It ends with a “call to arms”, but it is also an affirmation of the struggle for social justice . This poem resonated with Steve Biko and Black Consciousness activists because the call for a “new earth” to arise, the appeal to courage, freedom and healing, constituted the precise meaning and intent of the gospel of Black Consciousness . Margaret Walker does not so much dwell on the pain of the past or of lost hopes . She recognised the mood of confusion and fallacy that propelled 391 THE PAN-AFRICAN PANTHEON the foundation of the Black Consciousness Movement so many years later on another continent and under different circumstances . The poem is confident and positive in asserting the humanity of black people and of their capacity to become agents of their own liberation . -

Biko Met I Must Say, He Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba

LOVE AND MARRIAGE In Durban in early 1970, Biko met I must say, he Nontsikelelo (Ntsiki) Mashalaba Steve Biko Foundation was very politically who came from Umthatha in the Transkei. She was pursuing involved then as her nursing training at King Edward Hospital while Biko was president of SASO. a medical student at the I remember we University of Natal. used to make appointments and if he does come he says, “Take me to the station – I’ve Daily Dispatch got a meeting in Johannesburg tomorrow”. So I happened to know him that way, and somehow I fell for him. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch During his years at Ntsiki and Steve university in Natal, Steve had two sons together, became very close to his eldest Nkosinathi (left) and sister, Bukelwa, who was a student Samora (right) pictured nurse at King Edward Hospital. here with Bandi. Though Bukelwa was homesick In all Biko had four and wanted to return to the Eastern children — Nkosinathi, Cape, she expresses concern Samora, Hlumelo about leaving Steve in Natal and Motlatsi. in this letter to her mother in1967: He used to say to his friends, “Meet my lady ... she is the actual embodiment of blackness - black is beautiful”. Ntsiki Biko Daily Dispatch AN ATTITUDE OF MIND, A WAY OF LIFE SASO spread like wildfire through the black campuses. It was not long before the organisation became the most formidable political force on black campuses across the country and beyond. SASO encouraged black students to see themselves as black before they saw themselves as students. SASO saw itself Harry Nengwekhulu was the SRC president at as part of the black the University of the North liberation movement (Turfloop) during the late before it saw itself as a Bailey’s African History Archive 1960s. -

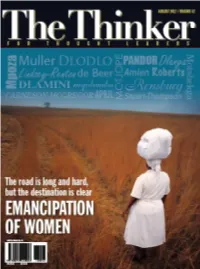

The Thinker Congratulates Dr Roots Everywhere

CONTENTS In This Issue 2 Letter from the Editor 6 Contributors to this Edition The Longest Revolution 10 Angie Motshekga Sex for sale: The State as Pimp – Decriminalising Prostitution 14 Zukiswa Mqolomba The Century of the Woman 18 Amanda Mbali Dlamini Celebrating Umkhonto we Sizwe On the Cover: 22 Ayanda Dlodlo The journey is long, but Why forsake Muslim women? there is no turning back... 26 Waheeda Amien © GreatStock / Masterfile The power of thinking women: Transformative action for a kinder 30 world Marthe Muller Young African Women who envision the African future 36 Siki Dlanga Entrepreneurship and innovation to address job creation 30 40 South African Breweries Promoting 21st century South African women from an economic 42 perspective Yazini April Investing in astronomy as a priority platform for research and 46 innovation Naledi Pandor Why is equality between women and men so important? 48 Lynn Carneson McGregor 40 Women in Engineering: What holds us back? 52 Mamosa Motjope South Africa’s women: The Untold Story 56 Jennifer Lindsey-Renton Making rights real for women: Changing conversations about 58 empowerment Ronel Rensburg and Estelle de Beer Adopt-a-River 46 62 Department of Water Affairs Community Health Workers: Changing roles, shifting thinking 64 Melanie Roberts and Nicola Stuart-Thompson South African Foreign Policy: A practitioner’s perspective 68 Petunia Mpoza Creative Lens 70 Poetry by Bridget Pitt Readers' Forum © SAWID, SAB, Department of 72 Woman of the 21st Century by Nozibele Qutu Science and Technology Volume 42 / 2012 1 LETTER FROM THE MaNagiNg EDiTOR am writing the editorial this month looks forward, with a deeply inspiring because we decided that this belief that future generations of black I issue would be written entirely South African women will continue to by women. -

Stephen Bantu Biko: an Agent of Change in South Africa’S Socio-Politico-Religious Landscape

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research Stephen Bantu Biko: An agent of change in South Africa’s socio-politico-religious landscape Author: This article examines and analyses Biko’s contribution to the liberation struggle in 1 Ramathate T.H. Dolamo South Africa from the perspective of politics and religion. Through his leading participation Affiliation: in Black Consciousness Movement and Black Theology Project, Biko has not only influenced 1Department of Philosophy, the direction of the liberation agenda, but he has also left a legacy that if the liberated and Practical and Systematic democratic South Africa were to follow, this country would be a much better place for all to Theology, University of live in. In fact, the continent as a whole through its endeavours in the African Union South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa underpinned by the African Renaissance philosophy would go a long way in forging unity among the continent’s nation states. Biko’s legacy covers among other things identity, Corresponding author: human dignity, education, research, health and job creation. This article will have far Ramathate Dolamo, reaching implications for the relations between the democratic state and the church in [email protected] South Africa, more so that there has been such a lack of the church’s prophecy for the past Dates: 25 years. Received: 12 Feb. 2019 Accepted: 22 May 2019 Keywords: Liberation; Black consciousness; Black theology; Self-reliance; Identity; Culture; Published: 29 July 2019 Religion; Human dignity. How to cite this article: Dolamo, R.T.H., 2019, ‘Stephen Bantu Biko: An Orientation agent of change in South Biko was born in Ginsberg near King William’s Town on 18 December 1946. -

The Beginnings of Anglican Theological Education in South Africa, 1848–1963

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 63, No. 3, July 2012. f Cambridge University Press 2012 516 doi:10.1017/S0022046910002988 The Beginnings of Anglican Theological Education in South Africa, 1848–1963 by PHILIPPE DENIS University of KwaZulu-Natal E-mail: [email protected] Various attempts at establishing Anglican theological education were made after the arrival in 1848 of Robert Gray, the first bishop of Cape Town, but it was not until 1876 that the first theological school opened in Bloemfontein. As late as 1883 half of the Anglican priests in South Africa had never attended a theological college. The system of theological education which developed afterwards became increasingly segregated. It also became more centralised, in a different manner for each race. A central theological college for white ordinands was established in Grahamstown in 1898 while seven diocesan theological colleges were opened for blacks during the same period. These were reduced to two in the 1930s, St Peter’s College in Johannesburg and St Bede’s in Umtata. The former became one of the constituent colleges of the Federal Theological Seminary in Alice, Eastern Cape, in 1963. n 1963 the Federal Theological Seminary of Southern Africa, an ecumenical seminary jointly established by the Anglican, Methodist, I Presbyterian and Congregational churches, opened in Alice, Eastern Cape. A thorn in the flesh of the apartheid regime, Fedsem, as the seminary was commonly called, trained theological students of all races, even whites at a later stage of its history, in an atmosphere -

Specialflash259-14-02-2017.Pdf

Issue 259 | 14 February 2017 ∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙∙ UBUNTU AWARDS 2017: “CELEBRATING OR TAMBO … IN HIS FOOTSTEPS” The annual awards, hosted by the Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO), are held to celebrate South African citizens who play an active role in projecting a positive image of South Africa internationally through their good work. The third annual Ubuntu Awards were on Saturday, 11 February, at the Cape Town International Convention Centre, under the theme: “Celebrating OR Tambo … In his Footsteps”. This year’s awards marked the centenary of struggle icon, Oliver Reginald Tambo, who was the longest-serving President of the African National Congress. Born in 1917, the late struggle stalwart, who passed away in 1993, would have turned 100 years old this year. Addressing guests at the glittering event, the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, said the ceremony had over the past three years proved to be an important and popular programmatic activity that followed the State of Nation Address. “It resonates well with our people and our collective desire to celebrate our very own leaders, and citizens who go beyond the call of duty in their respective industries to contribute to the betterment of this country as well as its general populace.” Reflecting on the theme of the event, Minister Nkoana-Mashabane said: “We are proud to celebrate the life and times of this national icon, a revered statesman and a gallant fighter of our liberation struggle. He worked with his generation to shape our country’s vision and constitutional value system as well as the foundations and principles of our domestic and foreign policy outlook.