DRISCOLL-DOCUMENT-2014.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Where He Did

Vol. 2 No. 9 October 1992 $4.00 and where he did Volume 2 Number 9 I:URI:-KA STRI:-eT October 1992 A m agazine of public affairs, the arts and theology 21 CoNTENTS TOPGUN Michael McGirr reports on gun laws and the calls for capital punishment in the 4 Philippines. COMMENT In this year of elections we are only as good 22 as our choices, says Peter Steele. Andrew DON'T KISS ME, HARDY Hamilton looks at the Columbus quin James Griffin concludes his series on the centary, and decides that the past must be Wren-Evatt letters. owned as well as owned up to (pS). 6 25 ORIENTATIONS LETTERS Peter Pierce and Robin Gerster take their pens to Shanghai and Saigon; Emmanuel 7 Santos and Hwa Goh take their cameras to COMMISSIONS AND OMISSIONS Tianjin. ICAC chief Ian Temby Margaret Simons talks to Australia's top speaks for himself: p 7 crime-busters. 34 11 BOOKS AND ARTS Cover photo: A member of Was the oldest part of the Pentateuch CAPITAL LETTER the Tianjing city planning office written by a woman? Kevin Hart reviews in Jei Fang Bei Road, three books by Harold Bloom, who thinks the 'Wall Street' of Tianjin. 12 it was; Robert Murray sizes up Columbus BLINDED BY THE LIGHT and colonialism (p38 ). Cover photo and photos pp25, 29 and 30 Bruce Williams visits the Columbus light by Emmanuel Santos; house in Santo Domingo, and wonders who Photo p27 by Hwa Goh; will be enlightened. 40 Photos p12 by Belinda Bain; FLASH IN THE PAN Photo p41 by Bill Thomas; 15 Reviews of the films Patriot Games Cartoons pp6, 36 and 3 7 by Dean Moore; Zentropa, Edward II, and Deadly. -

President Obama Triumphs in Elections Despite Enthusiasm

TONovember INFORM, 9, 2012 TO EDUCATE, AND TO STIMULATE ACTION THE SPOKESMAN Friday, November 9, 20121 THE Volume 72 | ISSUE 1 CALENDAR: LAST DAY OF CLASSES NOV. 30TH | FINAL EXAMS DEC. 3-10TH Campus fares well in storm SPECIAL TO THE SPOKESMAN By JOUR 206: Intro to Editing Class “We had 200 people in town for my grandma’s 90th birthday party this weekend and the show went on as planned,” says Morgan State senior Faven Amanuel, explaining how she passed the time as Hurricane Sandy hit Baltimore this week. She was out and about, ferrying people around while worrying that she’d be ticketed by cops who’d ordered folks to stay home. Other students played it safe, hunkering down as recommended by area officials. Most gathered around in Morgan View and campus dorms watching TV, playing games, eating, surfing the net—and in general enjoying two unexpected days off. Morgan State survived the storm just fine. Hurricane Sandy hit Baltimore City Monday morning with heavy winds, pelting rain and blasts of cold air. But the school didn’t lose power, didn’t sustain any serious damage from fallen trees and PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF US NAVY VIA CREATIVE COMMONS had no significant flooding in buildings or on the grounds. No students, faculty or staff were injured and classes began President Obama triumphs in running normally on Wednesday. “We have many to thank for helping to us get through past few days not least among elections despite enthusiasm gap them those who are what I choose to call ‘Morgan’s first responders,’” wrote By ASHLEY COX votes from key states like Ohio, President Obama’s policies has changed President David Wilson in an email to Spokesman Staff Writer Pennsylvania and Colorado, he was under due to the increase of “basic survival need” the Morgan community on Tuesday. -

Powers of Horror; an Essay on Abjection

POWERS OF HORROR An Essay on Abjection EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVES: A Series of the Columbia University Press POWERS OF HORROR An Essay on Abjection JULIA KRISTEVA Translated by LEON S. ROUDIEZ COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York 1982 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Kristeva, Julia, 1941- Powers of horror. (European perspectives) Translation of: Pouvoirs de l'horreur. 1. Celine, Louis-Ferdinand, 1894-1961 — Criticism and interpretation. 2. Horror in literature. 3. Abjection in literature. I. Title. II. Series. PQ2607.E834Z73413 843'.912 82-4481 ISBN 0-231-05346-0 AACR2 Columbia University Press New York Guildford, Surrey Copyright © 1982 Columbia University Press Pouvoirs de l'horreur © 1980 Editions du Seuil AD rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Clothbound editions of Columbia University Press books are Smyth- sewn and printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Contents Translator's Note vii I. Approaching Abjection i 2. Something To Be Scared Of 32 3- From Filth to Defilement 56 4- Semiotics of Biblical Abomination 90 5- . Qui Tollis Peccata Mundi 113 6. Celine: Neither Actor nor Martyr • 133 7- Suffering and Horror 140 8. Those Females Who Can Wreck the Infinite 157 9- "Ours To Jew or Die" 174 12 In the Beginning and Without End . 188 11 Powers of Horror 207 Notes 211 Translator's Note When the original version of this book was published in France in 1980, critics sensed that it marked a turning point in Julia Kristeva's writing. Her concerns seemed less arcane, her presentation more appealingly worked out; as Guy Scarpetta put it in he Nouvel Observateur (May 19, 1980), she now intro- duced into "theoretical rigor an effective measure of seduction." Actually, no sudden change has taken place: the features that are noticeable in Powers of Horror were already in evidence in several earlier essays, some of which have been translated in Desire in Language (Columbia University Press, 1980). -

THE EMERGENCE of BUDDHIST AMERICAN LITERATURE SUNY Series in Buddhism and American Culture

THE EMERGENCE OF BUDDHIST AMERICAN LITERATURE SUNY series in Buddhism and American Culture John Whalen-Bridge and Gary Storhoff, editors The Emergence of Buddhist American Literature EDITED BY JOHN WHALEN-BRIDGE GARY STORHOFF Foreword by Maxine Hong Kingston and Afterword by Charles Johnson Cover art image of stack of books © Monika3stepsahead/Dreamstime.com Cover art image of Buddha © maodesign/istockphoto Published by STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS ALBANY © 2009 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval systemor transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production by Diane Ganeles Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The emergence of Buddhist American literature / edited by John Whalen-Bridge and Gary Storhoff ; foreword by Maxine Hong Kingston ; afterword by Charles Johnson. p. cm. — (Suny series in Buddhism and American culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4384-2653-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. American literature—Buddhist authors—History and criticism. 2. American literature—20th century—History and criticism. 3. American literature—Buddhist influences. 4. Buddhism in literature. 5. Buddhism and literature—United States. I. Whalen-Bridge, John, 1961– II. Storhoff, Gary, 1947– PS153.B83E44 2009 810.9’382943—dc22 2008034847 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 John Whalen-Bridge would like to dedicate his work on The Emergence of Buddhist American Literature to his two sons, Thomas and William. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

The University of Chicago the History of Idolatry and The

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE HISTORY OF IDOLATRY AND THE CODEX DURÁN PAINTINGS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY KRISTOPHER TYLER DRIGGERS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2020 Copyright © 2020 by Kristopher Driggers All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ………..……………………………………………………………… iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………….. viii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .….………………………………...………………………….. ix INTRODUCTION: The History of Idolatry and the Codex Durán Paintings……………… 1 CHAPTER 1. Historicism and Mesoamerican Tradition: The Book of Gods and Rites…… 34 CHAPTER 2. Religious History and the Veintenas: Productive Misreadings and Primitive Survivals in the Calendar Paintings ………………………………………………………… 66 CHAPTER 3. Toward Signification: Narratives of Chichimec Religion in the Opening Paintings of the Historia Treatise…………………………………………………………… 105 CHAPTER 4. The Idolater Kings: Rulers and Religious History in the Later Historia Paintings……………………………………………………………………………. 142 CONCLUSION. Picturing the History of Idolatry: Four Readings ………………………… 182 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………………. 202 APPENDIX: FIGURES ……………………………………………………………………... 220 iii LIST OF FIGURES Some images are not reproduced due to restrictions. Chapter 1 1.1 Image of the Goddess Chicomecoatl, Codex Durán Folio 283 recto…………………..220 1.2 Priests, Codex Durán Folio 273 recto………………………………………………......221 1.3 Quetzalcoatl with devotional offerings, Codex Durán folio 257 verso………………...222 1.4 Codex Durán image of Camaxtli alongside frontispiece of Motolinia manuscript (caption only)..……………………………………………………………………….....223 1.5 Priests drawing blood with a zacatlpayolli in the corner, Codex Durán folio 248….….224 1.6 Priests wearing garlands and expressively gesturing, Codex Durán folio 246 recto.…..225 1.7 Tezcatlipoca, Codex Durán folio 241 recto ..………………………………….……….226 1.8 Image from Trachtenbuch, Christoph Weiditz, pp. -

CTC Sentinel 6

MARCH 2013 . VOL 6 . ISSUE 3 Contents Cooperation or Competition: FEATURE ARTICLE 1 Cooperation or Competition: Boko Haram and Ansaru After Boko Haram and Ansaru After the Mali Intervention By Jacob Zenn the Mali Intervention By Jacob Zenn REPORTS 9 AQIM’s Playbook in Mali By Pascale C. Siegel 12 Al-Shabab’s Tactical and Media Strategies in the Wake of its Battlefield Setbacks By Christopher Anzalone 16 The Upcoming Peace Talks in Southern Thailand’s Insurgency By Zachary Abuza 20 The Role of Converts in Al-Qa`ida- Related Terrorism Offenses in the United States By Robin Simcox and Emily Dyer 24 The Threat from Rising Extremism in the Maldives By Animesh Roul 28 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 32 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts A Cameroonian soldier stands in Dabanda by the car of the French family that was kidnapped on February 19. - AFP/Getty Images ince the nigerian militant group attacked schools, churches, cell phone Boko Haram1 launched its first towers, media houses, and government attack in northern Nigeria in facilities, including border posts, police September 2010, it has carried stations and prisons. Since January Sout more than 700 attacks that have 2012, however, a new militant group killed more than 3,000 people.2 Boko has attracted more attention in northern Haram primarily targets Nigerian Nigeria due to its threat to foreign government officials and security interests. Jama`at Ansar al-Muslimin About the CTC Sentinel officers, traditional and secular Muslim fi Bilad al-Sudan (commonly known as The Combating Terrorism Center is an leaders, and Christians.3 It has also Ansaru)4 announced that it split from independent educational and research Boko Haram in January 2012, claiming institution based in the Department of Social Sciences at the United States Military Academy, 1 The group Boko Haram identifies itself as Jama`at Ahl West Point. -

Governor Visits Oswego State

2013 - 2014 • Residence Hall ROOM A3 Relay for Life Housing Selection Campus Center hosts fundraiser for cancer research Friday, April 5, 2013 • THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF OSWEGO STATE UNIVERSITY • www.oswegonian.com VOLUME LXXVIII ISSUE VII On the Web Governor visits Oswego State Andrew Cuomo performs ceremonial budget signing in Sheldon Hall, promotes accomplishments Seamus Lyman “It has truly been an honor to work side the aisle from the governor, the lieutenant Asst. News Editor by side with Gov. Cuomo and his team and governor, there’s a lot of things I don’t real- [email protected] I thank him for his dedication to ensure that ly agree with them, I’ve got to say they have Gov. Andrew Cuomo visited Oswego our SUNY system of higher education and brought leadership and professionalism to State on a victory lap around New York af- all of the universities and colleges through- New York State,” Barclay said. ter passing his third consecutive state bud- out New York State continue to be the best When Cuomo made his way to the get on time. in the nation,” Stanley said. podium, he joked about the priorities of Several members of local and state Duffy spoke of the changes the governor the government. government attended the event, including is making in Albany. He described the at- “The first priority that we have to ad- Lt. Gov. Robert Duffy, Assemblyman Will mosphere in the state’s government. dress is, we have to unite as one, stand to- Barclay, R-Pulaski, Sen. David Valesky, D- “It’s people working together, there’s gether, and we have to defeat Michigan this Oneida, and Oswego Mayor Tom Gillen to a spirit of collegiality, it’s both sides of the weekend, and go Syracuse,” Cuomo said. -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

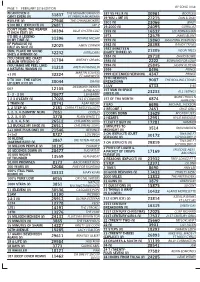

Page 1 February 2016 Edition by Song Title #Icanteven (I Can't Even)

PAGE 1 FEBRUARY 2016 EDITION BY SONG TITLE #ICANTEVEN (I 31837 THE NEIGHBOURHOOD 187 VS FELIX (V) 30961 BOOTLEG CAN'T EVEN) (V) FT FRENCH MONTANA 19 YOU + ME (V) 27215 DAN & SHAY #SELFIE (V) 27946 THE CHAINSMOKERS 1901 (V) 23066 BIRDY $100 BILL (EXPLICIT) (V) 26811 JAY-Z 19-2000 (V) 24095 GORILLAZ (DON'T FEAR) THE REAPER BLUE OYSTER CULT (7 INCH EDIT) (V) 30394 1959 (V) 16532 LEE KERNAGHAN 1973 12579 JAMES BLUNT (I'D BE) A LEGEND RONNIE MILSAP IN MY TIME (V) 31396 1979 (V) 19860 SMASHING PUMPKINS (IF PARADISE IS) AMEN CORNER 1982 (V) 28398 RANDY TRAVIS HALF AS NICE (V) 32025 1983 (NINETEEN 21305 NEON TREES (WIN, PLACE OR SHOW) INTRUDERS EIGHTY THREE) (V) SHE'S A WINNER (V) 32232 1984 (V) 29718 DAVID BOWIE (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY BRITNEY SPEARS (ALBUM VERSION) (V) 31784 1985 (V) 2222 BOWLING FOR SOUP 1994 (V) 25845 JASON ALDEAN (YOU MAKE ME FEEL LIKE) 31218 ARETHA FRANKLIN A NATURAL WOMAN (V) 1999 8496 PRINCE MARTIN SOLVEIG 1999 (EXTENDED VERSION) PRINCE +1 (V) 32224 FT SAM WHITE 4347 19TH NERVOUS 0 TO 100 - THE CATCH DRAKE 9087 THE ROLLING STONES UP (EXPLICIT) (V) 30044 BREAKDOWN DESMOND DEKKER 1-LUV 6733 E-40 007 12105 & THE ACES 1ST MAN IN SPACE 23233 ALL SEEING I 1 - 2 - 3 (V) 20677 LEN BARRY (FIRST) (V) BONE THUGS N 1 2 3 O'LEARY (V) 17028 DES O'CONNOR 1ST OF THA MONTH 6874 HARMONY 1 TRAIN (V) 30741 A$AP ROCKY 2 BAD 6696 MICHAEL JACKSON 1, 2 STEP (V) 2181 CIARA FT MISSY ELLIOTT 2 BECOME 1 7451 SPICE GIRLS 1, 2, 3, 4 (SUMPIN' NEW) 7051 COOLIO 2 DOORS DOWN 13629 MYSTERY JETS 1, 2, 3, 4 (V) 3778 PLAIN WHITE T'S 2 HEARTS 12951 KYLIE MINOGUE -

Julia Pascal Thesis 26 Sept.Pdf

The Absence of Female Jewish Characters on the Post-war English Stage: Thesis and Three Plays Julia Pascal PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television February 2016 Abstract This thesis examines representations of Jewish women on the British stage from 1945 to the present. I interrogate the lack of varied and realistic Jewish women characters in the canon and discuss this in relationship to my own published and performed plays. The absence of Jewish women in British modern theatre is explored historically and as a phenomenon influenced by both Christian and Jewish traditions. My research probes how stereotypes from Christian medieval tropes have been transformed and re- awoken, particularly since the 1980s, and how this has impacted the representation of Jewish women. I highlight the importance of Yiddish theatre as a dynamic space where Jewish women’s representation broke the rule of exclusion from public performance and offered a variety of complicated and complex roles on the international stage. The thesis examines the post-war loss of Yiddish theatre and the Yiddish language, and the subsequent effect on the development of Jewish female dramatic characterisation onstage. I reveal the vacuum left with the death of Yiddish, and how with the destruction of the language and culture, the representation of a variety of Jewish women’s roles, created by the Yiddishists, was forgotten and lost to subsequent generations. Post-war playwrights are discussed to explore modern female Jewish characters that have been produced for the English stage. The creation of Anne Frank, as a dramatic figure, is examined to understand how the adaptation of her diary impacts on the representation of Jewish women. -

Genesis for the New Space Age Secret Development of the Round Wing Plane, the Extra Terrestrials Inside the Earth, and the Arriv

Genesis for the New Space Age Secret Development of the Round Wing Plane, the Extra Terrestrials Inside the Earth, and the Arrival of the Outer Terrestrials 1980 by John B. Leith Genesis for the New Space Age Contents Dedication Introduction Prologue PART I - Space Race Chapter I Earth Under Surveillance Chapter II Early American Development of Prototype of Round Wing Planes Chapter III International Response to Unidentified Flying Objects Chapter IV U.S. Readies New Aerial Marvel for Possible German Conflict Chapter V Germans acquire U.S. Round Wing Plans Chapter VI U.S. Shares Secret of New Round Wing Planbe with Allies Chapter VII Allied Development and War-time Use of New Round Wing Plane Chapter VIII Germans Abandon Fatherland in Giant Subs and Their Model of the Round wing Planes Chapter IX Vanishing Germans Discover Mystery of Ages Chapter X Byrd Finds South Pole Entrance to Inner World Chapter XI Byrd Stalks The Missing Nazis Chapter XII U.S. Peacefully “invades” Inner World Chapter XIII Byrd’s Aerial Disaster Sets Post-War Postures PART II - The Inner World of Extra Terrestrials Chapter XIV Man From Atlantis Chapter XV U.S. Post-War Military Development of Anti-Gravity Principle Chapter XVI Germans Build Sovereign Nation in Inner Earth Chapter XVII Strangers in Our Skies Chapter XVIII A Day to Remember on Planet Earth (The First Battle with A Hostile Alien Craft from Outer Space) Chapter XIX A New Age Dawning Epilogue Appendix Social, Political, Economic and Religious Life, Inner Earth Notes Diagrams, Photos and Documents i Introduction Some of the most closely guarded secrets of this century -- and perhaps since time began will be discovered within the pages of this book.