Foreign Notices of South India Including Ceylon Scattered in Several Books and Journals Published by Learned Societies Not Easily Accessible to the General Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12Th 14Th Centuries)

Orientalia biblica et christiana 18 East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12th–14th centuries) Bearbeitet von Li Tang 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. XVII, 169 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 447 06580 1 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 550 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Christliche Kirchen & Glaubensgemeinschaften Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Li Tang East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China 2011 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 09465065 ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1 III Acknowledgement This book is the outcome of my research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund (Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, abbreviated as FWF) from May 2005 to April 2008. It could not be made possible without the vision of FWF in its support of researches and involvement in the international scientific community. I take this opportunity to give my heartfelt thanks, first and foremost, to Prof. Dr. Peter Hofrichter who has developed a passion for the history of East Syrian Christianity in China and who invited me to come to Austria for this research. He and his wife Hilde, through their great hospitality, made my initial settling-in in Salzburg very pleasant and smooth. My deep gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Dietmar W. Winkler who took over the leadership of this project and supervised the on-going process of the research out of his busy schedule and secured all the ways and means that facilitated this research project to achieve its goals. -

The South China Sea and Its Coral Reefs During the Ming and Qing Dynasties: Levels of Geographical Knowledge and Political Control Ulisesgrana Dos

East Asian History NUMBER 32/33 . DECEMBER 20061]uNE 2007 Institute of Advanced Studies The Australian National University Editor Benjamin Penny Associate Editor Lindy Shultz Editorial Board B0rge Bakken Geremie R. Barme John Clark Helen Dunstan Louise Edwards Mark Elvin Colin Jeffcott Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Kenneth Wells Design and Production Oanh Collins Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is a double issue of East Asian History, 32 and 33, printed in November 2008. It continues the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. This externally refereed journal is published twice per year. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 2 6125 5098 Fax +61 2 6125 5525 Email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to East Asian History, at the above address Website http://rspas.anu.edu.au/eah/ Annual Subscription Australia A$50 (including GST) Overseas US$45 (GST free) (for two issues) ISSN 1036-6008 � CONTENTS 1 The Moral Status of the Book: Huang Zongxi in the Private Libraries of Late Imperial China Dunca n M. Ca mpbell 25 Mujaku Dochu (1653-1744) and Seventeenth-Century Chinese Buddhist Scholarship John Jorgensen 57 Chinese Contexts, Korean Realities: The Politics of Literary Genre in Late Choson Korea (1725-1863) GregoryN. Evon 83 Portrait of a Tokugawa Outcaste Community Timothy D. Amos 109 -

Two Great Adventurers, Battuta and Polo, Affect the Medieval World

Two Great Adventurers, Battuta and Polo, Affect the Medieval World When you take a trip, how do you record what you did? Do you take pictures, and maybe post some of them on a social media site? Or you do send postcards or emails to your family and friends about your travels? Do you keep a journal to record events as they happen? Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo traveled in a time around the 13th and 14th centuries when recording events was not as easy as it is today. Upon their return to their homes, both Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo wrote about their adventures. Their stories were very influential in stimulating trade and travel in the regions they visited. Ibn Battuta’s desire to see the lands where his fellow Muslims lived led him across Asia, Africa, and Europe and the seas. His nearly thirty years of travel began when he was twenty-one when he set off for a pilgrimage to Mecca. After that, he traveled over 75,000 miles. Ibn Battuta traveled by joining trading caravans. Caravans were bands of travelers who journeyed together for security and mutual aid. He told of his adventures when he returned home to Morocco, and those who heard his stories thought they should be written down. The sultan of Morocco commissioned a young court secretary named Ibn Juzayy to listen to Ibn Battuta’s stories and record them. It took two years to write everything down, and when they were finished, the result was the Rihla, a story of travels centered on a pilgrimage. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Question of 'Race' in the Pre-Colonial Southern Sahara

The Question of ‘Race’ in the Pre-colonial Southern Sahara BRUCE S. HALL One of the principle issues that divide people in the southern margins of the Sahara Desert is the issue of ‘race.’ Each of the countries that share this region, from Mauritania to Sudan, has experienced civil violence with racial overtones since achieving independence from colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s. Today’s crisis in Western Sudan is only the latest example. However, very little academic attention has been paid to the issue of ‘race’ in the region, in large part because southern Saharan racial discourses do not correspond directly to the idea of ‘race’ in the West. For the outsider, local racial distinctions are often difficult to discern because somatic difference is not the only, and certainly not the most important, basis for racial identities. In this article, I focus on the development of pre-colonial ideas about ‘race’ in the Hodh, Azawad, and Niger Bend, which today are in Northern Mali and Western Mauritania. The article examines the evolving relationship between North and West Africans along this Sahelian borderland using the writings of Arab travellers, local chroniclers, as well as several specific documents that address the issue of the legitimacy of enslavement of different West African groups. Using primarily the Arabic writings of the Kunta, a politically ascendant Arab group in the area, the paper explores the extent to which discourses of ‘race’ served growing nomadic power. My argument is that during the nineteenth century, honorable lineages and genealogies came to play an increasingly important role as ideological buttresses to struggles for power amongst nomadic groups and in legitimising domination over sedentary communities. -

Saint Eric of Pordenone Catholic.Net

Saint Eric Of Pordenone Catholic.net A Franciscan missionary of a Czech family named Mattiussi, born at Villanova near Pordenone, Friuli, Italy, about 1286; died at Udine, 14 January 1331. About 1300 he entered the Franciscan Order at Udine. Towards the middle of the thirteenth century the Franciscans were commissioned by the Holy See to undertake missionary work in the interior of Asia. Among the missionaries sent there were John Piano Carpini, William Rubruquis, and John of Montecorvino. Odoric was called to follow them, and in April, 1318, started from Padua, crossed the Black Sea to Trebizond, went through Persia by way of the Tauris, Sultaniah, where in 1318 John XXII had erected an archbishopric, Kasham, Yezd, and Persepolis; he also visited Farsistan, Khuzistan, and Chaldea, and then went back to the Persian Gull. From Hormuz he went to Tana on the Island of Salsette, north of Bombay. Here he gathered the remains of Thomas of Tolentino, Jacopo of Padua, Pietro of Siena, and Demetrius of Tiflis, Franciscans who, a short time before, had suffered martyrdom, and took them with him so as to bury them in China. From Salsette he went to Malabar, Fondaraina (Flandrina) that lies north of Calicut, then to Cranganore that is south of Calicut, along the Coromandel Coast, then to Meliapur (Madras) and Ceylon. He then passed the Nicobar Islands on his way to Lamori, a kingdom of Sumoltra (Sumatra); he also visited Java, Banjarmasin on the southern coast of Borneo, and Tsiompa (Champa) in the southern part of Cochin China, and finally reached Canton in China. -

Ibn Battuta Travels the Islamic World

2/4/2020 Big Idea Ibn Battuta Travels the Islamic World Essential Question What do Ibn Battuta’s travels reveal about the Islamic world in the 1300s? 1 2/4/2020 Words To Know Hajj – an Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca; a religious duty that must be carried out at least once a lifetime by all adult Muslims who are capable of making the journey. Mecca – a city in Saudi Arabia that Muslims consider to be a holy city; the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad Pilgrimage – a religious journey. Let’s Set The Stage… Ibn Battuta was born in Tangier, part of modern-day Morocco, on February 25, 1304. He was raised by his family with a focus on education. As a result, Ibn Battuta’s urge to travel was spurred by interest in finding the best teachers and the best libraries in the world. Ibn Battuta was a Muslim student who studied law. He wanted to make the pilgrimage to Mecca, called the “hajj,” as soon as possible, out of eagerness and devotion to his Islamic faith. 2 2/4/2020 Ibn Battuta traveled for thirty years, mostly through lands where Islam was the predominate (main) religion and where people spoke Arabic because of the spread of the religion. When he returned from his travels, he wrote a book to reflect on his experiences throughout the Islamic world. On June 14, 1325, at the age of 21, Ibn Battuta rode out of Tangier on a donkey, the start of his journey to Mecca. 3 2/4/2020 Ibn Battuta stayed at a madrasas (Islamic college) as he made his way to Tunis. -

G.K. Mukanova IDENTIFICATION of AL-FARABI: PROBLEM TRENDS

ISSN 1563-0242 еISSN 2617-7978 Хабаршы. Журналистика сериясы. №1 (59) 2021 https://bulletin-journalism.kaznu.kz IRSTI 03.61; 19.21 https://doi.org/10.26577/HJ.2021.v59.i1.04 G.K. Mukanova Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Kazakhstan, Almaty, e-mail: [email protected] IDENTIFICATION OF AL-FARABI: PROBLEM TRENDS The article is devoted to the urgent problem of national identity, within the available information space. Monitoring of foreign publications revealed tendencies to unreasonably narrow or limit the impor- tance of the works of geniuses of scientific thought to ethnic boundaries. Using al-Farabi’s identification as an example, the author identifies and classifies system trends that demonstrate the duplication in time and space of “algorithms” that may contradict each other in the light of ideological concepts. Methods and materials relied on the basic principles of dialectics, logic and induction, comparative analysis and interdisciplinarity, in order to determine the subjective and objective factors of the forma- tion of national identity. The materials for the research were taken from sources obtained by means of digital technologies from the sites of foreign library funds and archival depositories of foreign research centers. We studied an array of thematic publications in English on Farabi studies in foreign countries. Digital copies of the publications of interest to us are indicated in the links. Scientific originality of the research lies in the detection of a complex of subjective and objective factors that influenced the external “design” of the identity of such an author of scientific treatises as al-Farabi in the context of different cultures. -

The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution

THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ROOTS OF THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann edited by GIDEON FREUDENTHAL PETER MCLAUGHLIN 13 Editors Preface Gideon Freudenthal Peter McLaughlin Tel Aviv University University of Heidelberg The Cohn Institute for the History Philosophy Department and Philosophy of Science and Ideas Schulgasse 6 Ramat Aviv 69117 Heidelberg 69 978 Tel Aviv Germany Israel The texts of Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann assembled in this volume are important contributions to the historiography of the Scientific Revolution and to the methodology of the historiography of science. They are of course also historical documents, not only testifying to Marxist discourse of the time but also illustrating typical European fates in the first half of the twentieth century. Hessen was born a Jewish subject of the Russian Czar in the Ukraine, participated in the October Revolution and was executed in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the purges. Grossmann was born a Jewish subject of the Austro-Hungarian Kaiser in Poland and served as an Austrian officer in the First World War; afterwards he was forced to return to Poland and then because of his revolutionary political activities to emigrate to Germany; with the rise to power of the Nazis he had to flee to France and then America while his family, which remained in Europe, perished in Nazi concentration camps. Our own acquaintance with the work of these two authors is also indebted to historical context (under incomparably more fortunate circumstances): the revival of Marxist scholarship in Europe in the wake of the student movement and the pro- fessionalization of history of science on the Continent. -

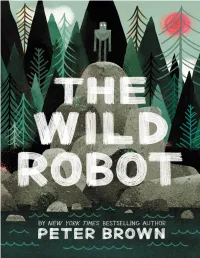

The Wild Robot.Pdf

Begin Reading Table of Contents Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. To the robots of the future CHAPTER 1 THE OCEAN Our story begins on the ocean, with wind and rain and thunder and lightning and waves. A hurricane roared and raged through the night. And in the middle of the chaos, a cargo ship was sinking down down down to the ocean floor. The ship left hundreds of crates floating on the surface. But as the hurricane thrashed and swirled and knocked them around, the crates also began sinking into the depths. One after another, they were swallowed up by the waves, until only five crates remained. By morning the hurricane was gone. There were no clouds, no ships, no land in sight. There was only calm water and clear skies and those five crates lazily bobbing along an ocean current. Days passed. And then a smudge of green appeared on the horizon. As the crates drifted closer, the soft green shapes slowly sharpened into the hard edges of a wild, rocky island. The first crate rode to shore on a tumbling, rumbling wave and then crashed against the rocks with such force that the whole thing burst apart. -

Hazar Türkçesi Ve Hazar Türkçesi Leksikoloji Tespiti Denemesi

HAZAR TÜRKÇESİ VE HAZAR TÜRKÇESİ LEKSİKOLOJİ TESPİTİ DENEMESİ Pınar Özdemir* Özet Eski Türkçenin diyalektleri arasında sayılan Hazar Türkçesi ma- alesef ardında yazılı eserler bırakmamıştır. Çalışmamızda bilinenden bilinmeyene metoduyla hareket ede- rek ilk önce mevcut Hazar Türkçesine ait kelimeleri derleyip, ortak özelliklerini tespit edip, mihenk taşlarımızı oluşturduk. Daha sonra Hazar Devleti’nin yaşadığı coğrafyada bu gün yaşayan Türk hak- larının dillerinden Karaçay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımçak ve Kumuk Türkçelerinin ortak kelimelerini tespit ettik. Bu ortak kelimelerin de leksik ve morfolojik özelliklerini belirledikten sonra birbirleriyle karşılaştırıp aralarındaki uyumu göz önüne sererek Hazar Türkçesi Leksikoloji Tespitini denedik. Anahtar Kelimeler : Hazar, Karaçay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımçak, Kumuk AbstraCt Unfortunately there is not left any written works behind Khazar Turkish which is deemed to be one of the dialects of old Turkish. In our work primarily key voices, forms and the words of Khazar Turkish have been determined with respect to the features of voice and forms of the existing words remaining from that period. Apart from these determined key features it have been determined the mu- tual aspects of Karachay-Malkar, Karaim, Krymchak and Kumuk Turkish which are known as the remnants of Khazar and it has been intended to reveal the vocabulary of Khazar Turkish. Key Words : Khazar, Karachay-Malkar, Karaim, Kırımchak, Ku- muk Önceleri Göktürk Devletine bağlı olan Hazar Hakanlığı bu devletin iç ve dış savaşlar neticesinde yıkıldığı 630–650 yılları arasındaki süreçte devlet olma temellerini atmıştır. Kuruluşundan sonra hızla büyüyen bu devlet VII. ve X. yüzyıllar arasında Ortaçağın en önemli kuvvetlerinden biri halini almıştır. Hazar Devleti coğrafi sınırlarını batıda Kiev, kuzeyde Bulgar, güneyde Kırım * [email protected] Karadeniz Araştırmaları • Kış 2013 • Sayı 36 • 189-206 Pınar Özdemir ve Dağıstan, doğuda Hārezm sınırlarına uzanan step bölgelerine kadar ge- nişletmiştir (Golden 1989: 147). -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III.