Distribution of Community Acquired Typhoid Fever Among Febrile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda

Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Ramkrishna Paul MSc Thesis WM-WQM.18-14 March 2018 Sketch Credits: Ramkrishna Paul Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Master of Science Thesis by Ramkrishna Paul Supervisor Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen Mentor Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink - Seyoum Examination committee Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen, Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink – Seyoum, Dr. Janwillem Liebrand This research is done for the partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Science degree at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, the Netherlands Delft March 2018 Although the author and UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education have made every effort to ensure that the information in this thesis was correct at press time, the author and UNESCO- IHE do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. © Ramkrishna Paul 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Abstract Water as it flows through a town is continuously affected and changed by social relations of power and vice-versa. In the course of its flow, it always benefits some, while depriving, or even in some cases harming others. The issues concerning distribution of water are closely intertwined with the distribution of risks, at the crux of which are questions related to how decisions related to water allocation and distribution are made. -

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report Management Sciences for Health (STAR-E) April 2011 This report was made possible through support provided by the US Agency for International Development, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 617‐A‐00‐09‐00006‐00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development. Strengthening TB and HIV & AIDS Responses in Eastern Uganda (STAR-E) Management Sciences for Health 784 Memorial Drive Cambridge, MA 02139 Telephone: (617) 250-9500 www.msh.org MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 MITOOMA MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 Prepared by STAR- E LQAS __________________________________________________________________________________ Mitooma Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 This document may be cited as: Author: Management Sciences in Health (STAR-E) and Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (STAR-SW) Title: Community knowledge and practices LQAS survey, 2010. Mitooma district report, May 2011. Contacts: Stephen K. Lwanga ([email protected]) and Edward Bitarakwate ([email protected]) Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 Page i Acknowledgements STAR-E acknowledges with appreciation the cooperation it has received from the partners contributing to the 2010 LQAS survey in Mitooma district: the communities that participated, the district authorities for oversight and supervision, the district officials for carrying out the survey under the management and guidance of the STAR-SW and STAR-E projects. STAR-E thanks STAR-SW for providing the electronic survey raw data sets as soon as they were ready. -

The Perception of Ishaka – Bushenyi Municipality Residents on Male Circumcision Towards Reduction of Hiv/Aids

THE PERCEPTION OF ISHAKA – BUSHENYI MUNICIPALITY RESIDENTS ON MALE CIRCUMCISION TOWARDS REDUCTION OF HIV/AIDS. BY PETER OLYAM (BMS/0151/62/DF) RESEARCH PROJECT PROPOSAL SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY JULY, 2013 KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY- WESTERN CAMPUS FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY P.O BOX 71 BUSHENYI UGANDA Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. v TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... vi DECLARATION ............................................................................................................................................. vii DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................................. ix LIST OF ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda Developing Subnational Estimates of Hiv Prevalence and the Number of People

UNAIDS 2014 | REFERENCE UGANDA DEVELOPING SUBNATIONAL ESTIMATES OF HIV PREVALENCE AND THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV UNAIDS / JC2665E (English original, September 2014) Copyright © 2014. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. METHODOLOGY NOTE Developing subnational estimates of HIV prevalence and the number of people living with HIV from survey data Introduction prevR Significant geographic variation in HIV Applying the prevR method to generate maps incidence and prevalence, as well as of estimates of the number of people living programme implementation, has been with HIV (aged 15–49 and 15 and older) and observed between and within countries. -

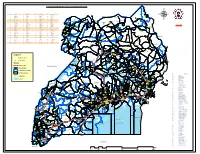

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-Mail: [email protected]; Website

2014 NPHC - Main Report National Population and Housing Census 2014 Main Report 2014 NPHC - Main Report This report presents findings from the National Population and Housing Census 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Plot 9 Colville Street, P.O. box 7186 Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org. Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2016, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report, Kampala, Uganda 2014 NPHC - Main Report FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are The Bureau would also like to thank the useful for planning and evidence-based Media for creating awareness about the decision making in any country. Such data Census 2014 and most importantly the are collected through Population Censuses, individuals who were respondents to the Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Census questions. Civil Registration Systems and other The census provides several statistics Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, among them a total population count which the Population and Housing Census remains is a denominator and key indicator used for the main source of demographic data. resource allocation, measurement of the extent of service delivery, decision making Uganda has undertaken five population and budgeting among others. These Final Censuses in the post-independence period. Results contain information about the basic The most recent, the National Population characteristics of the population and the and Housing Census 2014 was undertaken dwellings they live in. -

Prevalence and Correlates of Alzheimer's Disease and Related

Mubangizi et al. BMC Geriatrics (2020) 20:48 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-1461-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in rural Uganda: cross-sectional, population-based study Vincent Mubangizi1* , Samuel Maling1, Celestino Obua1 and Alexander C. Tsai1,2 Abstract Background: There is a paucity of data on the prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in sub-Saharan Africa. The aim of the study was to estimate the prevalence and correlates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in rural Uganda. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional, population-based study in a rural region of southwestern Uganda. The Brief Community Screening Instrument for Dementia was administered to a multi-stage area probability sample of 400 people aged 60 years and over. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate correlates of probable dementia. Results: Overall, 80 (20%) of the sample screened positive for dementia. On multivariable regression, we estimated the following correlates of probable dementia: age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.02 per year; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–1.03, p<0.001), having some formal education (AOR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.41–0.81, p = 0.001), exercise (AOR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.27–0.72, p = 0.001), and having a ventilated kitchen (AOR, 0.43; (95% CI, 0.24–0.77, p =0.001). Conclusions: In this population-based sample of older-age adults in rural Uganda, nearly one-fifth screened positive for dementia. Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Dementia, Sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda Background psychological factors, infectious diseases, genetic factors, Alzheimer’s disease, other dementias, and non- and carbon monoxide poisoning. -

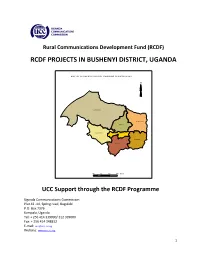

Rcdf Projects in Bushenyi District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN BUSHENYI DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F BU SH EN YI DIS TR ICT SH O W IN G SU B C O U NTIES N Ky amuh ung a Ky abug im bi Kakanju N yab uba re Bushen yi-Ish aka TC Kyeizob a Bum baire 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....…….3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Bushenyi district………….………...5 2- Map of Uganda showing Bushenyi district………..………………….………...……...14 10- Map of Bushenyi district showing sub counties………..………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Bushenyi district by sub counties…….....15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Bushenyi district…………………………………….……….…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

3. AMON DISSERTATION.Pdf

KNOWLEDGE ABOUT STIGMA AMONG PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS CASE STUDY OF ISHAKA ADVENTIST HOSPITAL BUSHENYI-ISHAKA MUNICIPALITY- BUSHENYI DISTRICT BY NIWAMANYA AMON DCM/0031/143/DU A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO SCHOOL OF ALLIED HEALTH SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DIPLOMA IN CLINCAL MEDICINEAND COMMUNITY HEALTH AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY WESTERN CAMPUS JULY 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this research dissertation is my own work and it has never been presented to any university or any other institution for any award or qualification whatsoever. Where the work of other people has been included, acknowledgement to this has been made in accordance to the text and preferences. This study has never been submitted before for either publication or award of any kind. NIWAMANYA AMON (DCM/0031/143/DU) SIGNATURE:………………………………………. DATE……………………………………………….. i APPROVAL This research dissertation has been produced under my close supervision and I therefore recommend the student for presentation. SUPERVISOR: TASHOBYA DANIEL KAMUGISHA SIGNATURE:…………………………………………….. DATE……………………………………………………… ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work first to the almighty God who has helped me through this far and also to my parents, Mr. Byamukama Patrick and Mrs. Mwebesa Loy for their endless support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I highly acknowledge the almighty god whose strength and wisdom have helped me immeasurably towards completing this work. I would also like to acknowledge and appreciate the valuable contribution and support from my lecturer and supervisor Mr. Tashobya Daniel Kamugisha who has tirelessly guided me through my research. I am heavily indebted to my family who financially and psychologically made my studies possible. -

COVID-19 Related Mental Health Burdens: Impact of Educational Level and Relationship Status Among Low Income Earners of Western Uganda

COVID-19 related mental health burdens: Impact of educational level and relationship status among low income earners of Western Uganda Lemuel Ann Monima ( [email protected] ) Kampala International University - Western Campus https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6998-1439 Ibe Michael Usman Kampala International University - Western Campus Kenneth Iceland Kasozi The University of Edinburgh Eric . Osamudiamwen Aigbogun, Jr Kampala International University - Western Campus Victor Archibong Bassey Kampala International University - Western Campus Josiah Ie Kampala International University - Western Campus Robinson Ssebuufu Kampala International University - Western Campus Adam Moyosore Afodun Kampala International University - Western Campus Swase Dominic Terkimbi Kampala International University - Western Campus Ngala Elvis Mbiydzenyuy The Copperbelt University School of Medicine Azeez Adeoye Kampala International University - Western Campus Joshua Ojodale Aruwa Kampala International University - Western Campus Odoma Saidi Kampala International University - Western Campus Fred Ssempijja Kampala International University - Western Campus John Tabakwot Ayuba Kampala International University - Western Campus Hope Onohuean Kampala International University - Western Campus Stellamaris Kembabazi Kampala International University - Western Campus Theophilus Pius Kampala International University - Western Campus Viola Nankya Kampala International University - Western Campus Kevin Matama Kampala International University - Western Campus Rachael Henry Ahmadu -

RCDF PROJECTS in MITOOMA DISTRICT, UGANDA UCC Support

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN MITOOMA DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F M ITO O M A D IST R IC T SH O W IN G SU B C O U N T IE S N Kiyan ga Biter eko Kan yab wan ga Mitooma Kash en sh er o Mutara Kab ira 20 0 20 40 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..………..……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….….…..………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….….……..…..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….….…....5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….….........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….………..13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Mitooma district………….………….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Mitooma district………..………………….………...……….14 10- Map of Mitooma district showing sub counties………..…………………………….15 11- Table showing the population of Mitooma district by sub counties………...15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Mitooma district…………………………………….……….…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

School Location; School Planning; *Secondexy Schools; Site Selection IDENTIFIERS School Eapping; *Uganda

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 190 EA 005 923 AUTHOR Gould, V. T. S. TITLE Planning the Location of Schools: Ankole District, Uganda. Case Studies -- 3. INSTITUTION United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organi:mtion, Paris (France). International Inst. for Educat%onal Planning. REPORT NO ISBN-9:!-803-1057-7 PUB DATE 73 NOTE 88p. AVAILABLE FROM Unipub1 Inc., P.O. Box 443, New York, New York 10016 (Order number ISBN 92-803-1057-7, $10.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.15 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Case Studies; Educational Planning; *Elementary Schools; Foreign Countries; Geographic Location; Maps; Methodology; *Planning; *School Demography; School Mstricts; *School Location; School Planning; *Secondexy Schools; Site Selection IDENTIFIERS School Eapping; *Uganda ABSTRACT Ahkole District, Uganda, is typical of many developing areas of Africa, characterized by rapid population change (a result of both growth and redistribution), inadequate school provision, and severe financial constraints. The study relates the present patterns and organization of elementary and secondary level educational provision to the existing and projected population distribution. Population density is seen as a crucial variable affecting the choice of strategy for the development of the school map. Basic techniques of locational analysis are used to suggest a policy for expanding the elementary level system and to identify suitable locations for new secondary level schools. (Photographs may reproduce poorly.)(Author) Planning the location of schools: case studies-.3. An IIEP research project directed by'Jacques Hallak U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCE° EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Planning the location of schools: Ankole District, Uganda "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL BY MICRO.