Prevalence and Correlates of Alzheimer's Disease and Related

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL MEDICAL STORES NMS WEEKLY DISPATCH REPORT:25Th Feb - 2Nd Mar 2020

NATIONAL MEDICAL STORES NMS WEEKLY DISPATCH REPORT:25th Feb - 2nd Mar 2020 Date District Facility Nature 3/2/2020 LWENGO LWENGO DISTRICT EMHS 3/2/2020 BUSHENYI BUSHENYI DISTRICT EMHS 3/2/2020 BUTAMBALA BUTAMBALA DISTRICT EMHS 3/2/2020 BUTAMBALA GOMBE HOSPITAL EMHS 3/2/2020 BUKWO BUKWO DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 3/2/2020 KWEEN KWEEN DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/28/2020 KAMPALA MULAGO HOSPITAL EMHS 2/28/2020 RAKAI RAKAI HOSPITAL EMHS 2/28/2020 SSEMBABULE SSEMBABULE DISTRICT EMHS 2/28/2020 KYOTERA KALISIZO HOSPITAL EMHS 2/28/2020 KIRUHURA KIRUHURA DISTRICT EMHS 2/28/2020 NTUNGAMO NTUNGAMO DISTRICT EMHS 2/28/2020 SOROTI SOROTI DISTRICT OXGYEN 2/27/2020 IBANDA IBANDA DISTRICT EMHS 2/27/2020 KANUNGU KAMBUGA HOSPITAL SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 LWENGO LWENGO DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 ISINGIRO ISINGIRO DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 MBARARA MBARARA DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 RWAMPARA RWAMPARA DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 BUHWEJU BUHWEJU DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 KANUNGU KANUNGU DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 KISORO KISORO HOSPITAL EMHS 2/27/2020 RUKUNGIRI RUKUNGIRI DISTRICT SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2/27/2020 LYANTONDE LYANTONDE DISTRICT/HOSPITAL EMHS 2/27/2020 KISORO KISORO DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 RUBANDA RUBANDA DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 KAMPALA MULAGO HOSPITAL EMHS 2/27/2020 SHEEMA SHEEMA DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 BUSHENYI BUSHENYI DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 RUBIRIZI RUBIRIZI DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 LWENGO LWENGO DISTRICT VACCINE TOOLS 2/27/2020 RUKUNGIRI RUKUNGIRI DISTRICT -

The Case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda

Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Ramkrishna Paul MSc Thesis WM-WQM.18-14 March 2018 Sketch Credits: Ramkrishna Paul Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Master of Science Thesis by Ramkrishna Paul Supervisor Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen Mentor Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink - Seyoum Examination committee Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen, Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink – Seyoum, Dr. Janwillem Liebrand This research is done for the partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Science degree at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, the Netherlands Delft March 2018 Although the author and UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education have made every effort to ensure that the information in this thesis was correct at press time, the author and UNESCO- IHE do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. © Ramkrishna Paul 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Abstract Water as it flows through a town is continuously affected and changed by social relations of power and vice-versa. In the course of its flow, it always benefits some, while depriving, or even in some cases harming others. The issues concerning distribution of water are closely intertwined with the distribution of risks, at the crux of which are questions related to how decisions related to water allocation and distribution are made. -

Contact List for District Health O Cers & District Surveillance Focal Persons

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF HEALTH Contact List for District Health Ocers & District Surveillance Focal Persons THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF HEALTH FIRST NAME LAST NAME E-MAIL ADDRESS DISTRICT TITLE MOBILEPHONE Adunia Anne [email protected] ADJUMANI DHO 772992437 Olony Paul [email protected] ADJUMANI DSFP 772878005 Emmanuel Otto [email protected] AGAGO DHO 772380481 Odongkara Christopher [email protected] AGAGO DSFP 782556650 Okello Quinto [email protected] AMOLATAR DHO 772586080 Mundo Okello [email protected] AMOLATAR DSFP 772934056 Sagaki Pasacle [email protected] AMUDAT DHO 772316596 Elimu Simon [email protected] AMUDAT DSFP 752728751 Wala Maggie [email protected] AMURIA DHO 784905657 Olupota Ocom [email protected] AMURIA DSFP 771457875 Odong Patrick [email protected] AMURU DHO 772840732 Okello Milton [email protected] AMURU DSFP 772969499 Emer Mathew [email protected] APAC DHO 772406695 Oceng Francis [email protected] APAC DSFP 772356034 Anguyu Patrick [email protected] ARUA DHO 772696200 Aguakua Anthony [email protected] ARUA DSFP 772198864 Immelda Tumuhairwe [email protected] BUDUDA DHO 772539170 Zelesi Wakubona [email protected] BUDUDA DSFP 782573807 Kiirya Stephen [email protected] BUGIRI DHO 772432918 Magoola Peter [email protected] BUGIRI DSFP 772574808 Peter Muwereza [email protected] BUGWERI DHO 782553147 Umar Mabodhe [email protected] BUGWERI DSFP 775581243 Turyasingura Wycliffe [email protected] BUHWEJU DHO 773098296 Bemera Amon [email protected] -

Case Study of Rufuuha Wetland, Ntungamo District

Land Restoration Training Programme Keldnaholt, 112 Reykjavik, Iceland Final project 2018 ASSESSING THE PERCEPTION OF FRINGE COMMUNITIES ON WETLAND MANAGEMENT IN UGANDA: CASE STUDY OF RUFUUHA WETLAND, NTUNGAMO DISTRICT Dinnah Tumwebaze Ntungamo District Local Government P.O Box 01 Ntungamo [email protected] Supervisor Victor Pajuelo Madrigal SVARMI [email protected] ABSTRACT To ensure the health and wellbeing of the human population, wetlands should be managed sustainably to continue the services they provide and the justifiable exploitation of the earth’s resources. Cautious action needs to be directed towards the maintenance of the significant support systems of the ecosystem services on the globe, such as wetlands. This study aimed to assess the perception of fringe communities on the management of the Rufuuha wetland, Ntungamo District in south-western Uganda. The methodologies used in this study included simple random sampling. Results indicated that the state of Rufuuha wetland has been notably influenced by a lack of awareness of the wetland laws and regulations and a high local illiteracy level on sustainable wetland management. There is a need for sensitization of the community and an encouraging bottom-up approach in formulation and implementation of wetland laws. Key words: Perception, fringe community, wetland management, Ntungamo District. UNU Land Restoration Training Programme This paper should be cited as: Tumwebaze D (2018) Assessing the perception of fringe communities on wetland management Uganda: A case study of Rufuuha wetland, Ntungamo District. United Nations University Land Restoration Training Programme [final project] http://www.unulrt.is/static/fellows/document/tumwebeze2018.pdf ii UNU Land Restoration Training Programme TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

A Review of Land Tenure and Land Use Planning in the Six Kagera TAMP Districts in Uganda

A Review of Land Tenure and Land use Planning in the six Kagera TAMP Districts in Uganda BdBernard BhBashaas ha School of Agricultural Sciences, Makerere University. Outline of Presentation Background Objective and Methodology Research Questions PliiPreliminary Fi Fidindings Land tenure structure Background KLKey Laws and regu lati ons rel ati ng t o th e ownership, management and transfer of land and re ltdlated resources i n Ug Uand a. The Constitution • The Land Act (1998), • The Land regulations of 2004 • The Physical planning Act of 2010. This act specifically provides for the design and implementation of land use plans. Background cont’d Other Relevant Laws: • The land acquisition Act, • The Water Act and associated water resources regulati on s, • The National Forestry and tree planting Act (2003), • The National Environment Regulations (2001), • The mortgage Act, • the registration of titles Act and the rent restriction Act. Objective & Methodology Object ive To achieve a deeper understanding of the land tenure structure andld land use p lanni ng i n th e six Kagera TAMP districts Highlight the constraints and identify the opportun ities f or pri ority it acti on. Methodology A combination of literature review and key informant interviews with district level staff. Research Questions What is the current land tenure structure and its distribution in Uganda and in the six districts of the Kagera TAMP project? What are the strategies and plans in place to improve the land tenure structure in Uganda and in the six Kagera TAMP project districts, in particular? Do land use plans exist at the National level and in the six Kagera TAMP project districts? HdhiildHow do the existing land use pl ans compare (i n content, design process (approach) and coordination arrangements) with best practices. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

Assessment of the Capacity of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, and Resources to Prevent and Control Noncommunicable Diseases

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Public Health Theses School of Public Health January 2014 Assessment Of The aC pacity Of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, And Resources To Prevent And Control Noncommunicable Diseases Hilary Eileen Rogers Yale University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl Recommended Citation Rogers, Hilary Eileen, "Assessment Of The aC pacity Of Ugandan Health Facilities, Personnel, And Resources To Prevent And Control Noncommunicable Diseases" (2014). Public Health Theses. 1246. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl/1246 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Health at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Theses by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSMENT OF THE CAPACITY OF UGANDAN HEALTH FACILITIES, PERSONNEL, AND RESOURCES TO PREVENT AND CONTROL NONCOMMUNICABLE DISEASES By Hilary Rogers A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Yale School of Public Health in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Public Health in the Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology New Haven, Connecticut April 2014 Readers: Dr. Adrienne Ettinger, Yale School of Public Health Dr. Jeremy Schwartz, Yale School of Medicine ABSTRACT Due to the rapid rise of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), the Uganda Ministry of Health (MoH) has prioritized NCD prevention, early diagnosis, and management. In partnership with the World Diabetic Foundation, MoH has embarked on a countrywide program to build capacity of the health facilities to address NCDs. -

Ntungamo District HRV Profile.Pdf

Ntungamo District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 NTUNGAMO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE a ACKNOWLEDGEMENT On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Odong Martin, Disaster Management Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/ DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred-Early Warning system Programmer. My appreciation also goes to Ntungamo District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees NTUNGAMO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The multi-hazard vulnerability profile outputs from this assessment was a combination of spatial modeling using socio-ecological spatial layers (i.e. DEM, Slope, Aspect, Flow Accumulation, Land use, vegetation cover, hydrology, soil types and soil moisture content, population, socio-economic, health facilities, accessibility, and meteorological data) and information captured from District Key Informant interviews and sub-county FGDs using a participatory approach. -

Inside Healthy Child Uganda News Letter

INSID E H E ALTHY CHILD UGANDA NE W S LETTER Annual news letter , October , 2014 SPECIAL THANKS TO THE EDITORIAL TEAM Inside Healthy Child Uganda is an annual newsletter aimed at sharing knowledge, Paskazia Tumwesigye( Writer, Editor, experiences and lessons learned in Graphics) Model Evaluation and Commu- implementing Maternal Newborn and Child nication Officer– Healthy Child Uganda Health (MNCH) interventions under the part- Teddy Kyomuhangi (Editor) nership of Healthy Child Uganda (HCU). Project Manager -Healthy Child Uganda This year’s newsletter is the first edition of Anthony Nimukama (Writer) Inside Healthy Child Uganda, We hope that HMIS officer Bushenyi District the articles will enrich your understanding of Dr. Elizabeth Kemigisha (Writer) MNCH and will contribute to improving Pediatrician-Mbarara University of Science MNCH related programs. and Technology In the next issue Inside Healthy Child Ugan- Kim Manalili (Editor) da will feature articles from partners imple- menting MNCH programs in the region, you Project coordinator are therefore invited to contribute. Healthy Child Uganda– Canada Thank You to Our Partners and Supporters News and Events Healthy Child Uganda Meets Minister Ruhakana Rugunda Left, -Right Dr. Elias KumbaKumba (MUST), Dr. Edward Mwesigye (DHO Bushenyi), Minister Ruhakana Rugunda, Kim Manalili (HCU -Canada), Teddy Kyomuhangi (HCU), from the back ( right –Left ), Dr. Celestine Barigye (MOH) Dr. Kagwa Paul (MOH) It was an excitement for Healthy Child Uganda to receive In his remarks Rugunda commended the MamaToto an Invitation from Hon. Ruhakana Rugunda; the Minister approach that HCU uses to ensure sustainable com- for Health who has recently been appointed the Prime munity based programs. -

The Perception of Ishaka – Bushenyi Municipality Residents on Male Circumcision Towards Reduction of Hiv/Aids

THE PERCEPTION OF ISHAKA – BUSHENYI MUNICIPALITY RESIDENTS ON MALE CIRCUMCISION TOWARDS REDUCTION OF HIV/AIDS. BY PETER OLYAM (BMS/0151/62/DF) RESEARCH PROJECT PROPOSAL SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY JULY, 2013 KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY- WESTERN CAMPUS FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY P.O BOX 71 BUSHENYI UGANDA Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. v TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... vi DECLARATION ............................................................................................................................................. vii DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................................. ix LIST OF ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... -

To 10Thjune 2019

NATIONAL MEDICAL STORES STMay NMS WEEKLY DELIVERY REPORT: 31 to 10thJune 2019 Dispatch Date Destination Nature Of Delivery 10-June Kalisizo Hospital EMHS 10-June Butambala District SOAP $ IV FLUIDS 10-June Itojo Hospital EMERGENCY 10-June Mpigi District SOAP $ IV FLUIDS 10-June Ibanda District EMHS 10-June Ntungamo District EMHS 10-June Kween District LPG 10- June Kapchorwa District LPG 10- June BukwoDistrict LPG 8- June Masaka District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 8- June Ibanda District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 8- June Kiruhura District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 8- June Rakai District/Rakai Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 8- June AdjumaniDistrict OXYGEN Kyotera District/Kalisizo 8- June Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7- June Lwengo District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7- June Kalungu District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7- June NgoraDistrict EMHS 7- June Bukedea District EMHS 7- June Kabale District SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7-June Masaka Regional Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7-June Kabale Regional Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7-June KisoroDistrict/Kisoro Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 7-June Rubanda District EMHS 7-June KapchorwaDistrict HEPATITIS B VACCINE 7-June Bugiri District HEPATITIS B VACCINE 7-June Kabale District EMHS 7-June Atutur Hospital EMHS 6-June NtungamoDistrict/Itojo Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 6-June LuukaDistrict HEPATITIS B VACCINE 6-June Kamuli District HEPATITIS B VACCINE Lyantonde District/Lyantonde 6-June Hospital SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2-June Bukwo District EMHS/ SOAP & IV FLUIDS 2-June Kabale Regional Hospital EMHS 1-June Buvuma District LPG 1-June Amolatar District EMHS 1-June Kitagata Hospital OXYGEN 1-June Mbarara University Hospital EMHS 1-June Masaka Regional Hospital EMHS 1-June Serere District EMHS 1-June Bwera Hospital OXYGEN 31-May Kaliziso Hospital OXYGEN Katakwi District/Katakwi 31-May General Hospital EMHS 31-May Moroto District EMHS 31-May Napak District EMHS 31-May Gombe Hospital OXYGEN 31-May Kalangala District LPG 31-May Kapchorwa Hospital OXYGEN We strive to serve you better. -

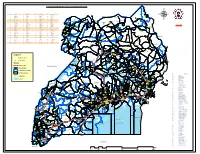

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !.