A Case Study of the Trees for Global Beneffts Project, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

The Case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda

Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Ramkrishna Paul MSc Thesis WM-WQM.18-14 March 2018 Sketch Credits: Ramkrishna Paul Water governance in small towns at the rural-urban intersection: the case of Bushenyi-Ishaka, Uganda Master of Science Thesis by Ramkrishna Paul Supervisor Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen Mentor Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink - Seyoum Examination committee Dr. Margreet Zwarteveen, Dr. Jeltsje Kemerink – Seyoum, Dr. Janwillem Liebrand This research is done for the partial fulfilment of requirements for the Master of Science degree at the UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, Delft, the Netherlands Delft March 2018 Although the author and UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education have made every effort to ensure that the information in this thesis was correct at press time, the author and UNESCO- IHE do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. © Ramkrishna Paul 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Abstract Water as it flows through a town is continuously affected and changed by social relations of power and vice-versa. In the course of its flow, it always benefits some, while depriving, or even in some cases harming others. The issues concerning distribution of water are closely intertwined with the distribution of risks, at the crux of which are questions related to how decisions related to water allocation and distribution are made. -

Mitooma District

National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles Mitooma District April 2017 National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Mitooma District This report presents findings of National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the UBOS Head Office, Statistics House. Plot 9 Colville Street, P. O. Box 7186, Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: +256-414 706000 Fax: +256-414 237553; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series, Kampala, Uganda. National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific profiles – Mitooma District FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are useful for planning and evidence-based decision making in any country. Such data are collected through Population Censuses, Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Civil Registration Systems and other Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, the Population and Housing Census remains the main source of demographic data, especially at the sub-national level. Population Census taking in Uganda dates back to 1911 and since then the country has undertaken five such Censuses. The most recent, the National Population and Housing Census 2014, was undertaken under the theme ‘Counting for Planning and Improved Service Delivery’. The enumeration for the 2014 Census was conducted in August/September 2014. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) worked closely with different Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as Local Governments (LGs) to undertake the census exercise. -

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report

Mitooma District Community Knowledge and Practices LQAS Survey Report Management Sciences for Health (STAR-E) April 2011 This report was made possible through support provided by the US Agency for International Development, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 617‐A‐00‐09‐00006‐00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development. Strengthening TB and HIV & AIDS Responses in Eastern Uganda (STAR-E) Management Sciences for Health 784 Memorial Drive Cambridge, MA 02139 Telephone: (617) 250-9500 www.msh.org MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 MITOOMA MITOOMA DISTRICT COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE AND PRACTICES SURVEY REPORT APRIL 2011 Prepared by STAR- E LQAS __________________________________________________________________________________ Mitooma Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 This document may be cited as: Author: Management Sciences in Health (STAR-E) and Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (STAR-SW) Title: Community knowledge and practices LQAS survey, 2010. Mitooma district report, May 2011. Contacts: Stephen K. Lwanga ([email protected]) and Edward Bitarakwate ([email protected]) Mitooma District Knowledge and Practices Survey Report, 2010 Page i Acknowledgements STAR-E acknowledges with appreciation the cooperation it has received from the partners contributing to the 2010 LQAS survey in Mitooma district: the communities that participated, the district authorities for oversight and supervision, the district officials for carrying out the survey under the management and guidance of the STAR-SW and STAR-E projects. STAR-E thanks STAR-SW for providing the electronic survey raw data sets as soon as they were ready. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Who and Why? Understanding Rural Out-Migration in Uganda

Article Who and Why? Understanding Rural Out-Migration in Uganda Samuel Tumwesigye 1,2,* , Lisa-Marie Hemerijckx 1 , Alfonse Opio 3, Jean Poesen 1,4 , Matthias Vanmaercke 1,5, Ronald Twongyirwe 2 and Anton Van Rompaey 1 1 Division of Geography and Tourism, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200E, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium; [email protected] (L.-M.H.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (M.V.); [email protected] (A.V.R.) 2 Department of Environment and Livelihoods Support Systems, Faculty of Interdisciplinary Studies, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Mbarara P.O. Box 1410, Uganda; [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Gulu University, Gulu P.O. Box 166, Uganda; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Earth Sciences and Spatial Management, Maria-Curie Sklodowska University, Krasnicka 2D, 20-718 Lublin, Poland 5 Department of Geography, UR SPHERES, University of Liège, 4000 Liege, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Rural–urban migration in developing countries is considered to be a key process for sustainable development in the coming decades. On the one hand, rural–urban migration can contribute to the socioeconomic development of a country. On the other hand, it also leads to labor transfer, brain-drain in rural areas, and overcrowded cities where planning is lagging behind. In order to get a better insight into the mechanisms of rural–urban migration in developing countries, Citation: Tumwesigye, S.; this paper analyzes motivations for rural–urban migration from the perspective of rural households Hemerijckx, L.-M.; Opio, A.; Poesen, in Uganda. -

The Perception of Ishaka – Bushenyi Municipality Residents on Male Circumcision Towards Reduction of Hiv/Aids

THE PERCEPTION OF ISHAKA – BUSHENYI MUNICIPALITY RESIDENTS ON MALE CIRCUMCISION TOWARDS REDUCTION OF HIV/AIDS. BY PETER OLYAM (BMS/0151/62/DF) RESEARCH PROJECT PROPOSAL SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY JULY, 2013 KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY- WESTERN CAMPUS FACULTY OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND DENTISTRY P.O BOX 71 BUSHENYI UGANDA Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. v TABLE OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... vi DECLARATION ............................................................................................................................................. vii DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................................. ix LIST OF ABREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda Developing Subnational Estimates of Hiv Prevalence and the Number of People

UNAIDS 2014 | REFERENCE UGANDA DEVELOPING SUBNATIONAL ESTIMATES OF HIV PREVALENCE AND THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV UNAIDS / JC2665E (English original, September 2014) Copyright © 2014. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Information Production Unit. Reproduction of graphs, charts, maps and partial text is granted for educational, not-for-profit and commercial purposes as long as proper credit is granted to UNAIDS: UNAIDS + year. For photos, credit must appear as: UNAIDS/name of photographer + year. Reproduction permission or translation-related requests—whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution—should be addressed to the Information Production Unit by e-mail at: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information published in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. METHODOLOGY NOTE Developing subnational estimates of HIV prevalence and the number of people living with HIV from survey data Introduction prevR Significant geographic variation in HIV Applying the prevR method to generate maps incidence and prevalence, as well as of estimates of the number of people living programme implementation, has been with HIV (aged 15–49 and 15 and older) and observed between and within countries. -

Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-Mail: [email protected]; Website

2014 NPHC - Main Report National Population and Housing Census 2014 Main Report 2014 NPHC - Main Report This report presents findings from the National Population and Housing Census 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Plot 9 Colville Street, P.O. box 7186 Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org. Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2016, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report, Kampala, Uganda 2014 NPHC - Main Report FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are The Bureau would also like to thank the useful for planning and evidence-based Media for creating awareness about the decision making in any country. Such data Census 2014 and most importantly the are collected through Population Censuses, individuals who were respondents to the Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Census questions. Civil Registration Systems and other The census provides several statistics Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, among them a total population count which the Population and Housing Census remains is a denominator and key indicator used for the main source of demographic data. resource allocation, measurement of the extent of service delivery, decision making Uganda has undertaken five population and budgeting among others. These Final Censuses in the post-independence period. Results contain information about the basic The most recent, the National Population characteristics of the population and the and Housing Census 2014 was undertaken dwellings they live in. -

USAID/Uganda's District-Based Technical Assistance (DBTA)

ANNEX A. STATEMENT OF WORK STATEMENT OF WORK FOR EVALUATION OF USAID/UGANDA’S DISTRICT-BASED TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE (DBTA) PROJECTS, STRENGTHENING TUBERCULOSIS AND HIV/AIDS RESPONSES (STAR) PROJECTS IN EAST, EAST-CENTRAL, AND SOUTH-WEST UGANDA INTRODUCTION The STAR projects in East, East-Central, and South-West Uganda were the first in USAID/Uganda’s District Based Technical Assistance (DBTA) model featuring regional focus on improving accessibility, quality, and availability of integrated health service delivery as well as health financing and management. The STAR program is implemented by Management Sciences for Health (MSH) in East Uganda, by John Snow International (JSI) in East-Central Uganda, and by Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF) in South-West Uganda, covering thirty- four districts in total. Working closely with the Ministry of Health and through district health management teams (DHMTs), district councils, health facilities, and communities, the projects’ goal is to increase access to, coverage of, and utilization of quality comprehensive HIV/AIDS and TB prevention, care, and treatment services within district health facilities and their respective communities. This will be achieved through the following objectives: (a) strengthening decentralized HIV/AIDS and TB service delivery systems; (b) improving the quality and efficiency of HIV/AIDS and TB service delivery within health facilities; (c) strengthening networks and referrals systems to improve access to, coverage of, and use of HIV/AIDS and TB services; and (d) increasing demand for comprehensive HIV/AIDS and TB prevention, care, and treatment services. All three STAR projects are designed to strengthen systems at the decentralized level to facilitate improved delivery and uptake of HIV/AIDS and TB services, including district-led performance reviews to help identify coverage and service gaps. -

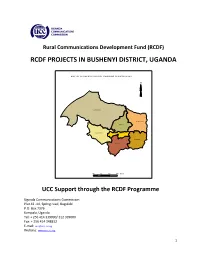

Rcdf Projects in Bushenyi District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN BUSHENYI DISTRICT, UGANDA MA P O F BU SH EN YI DIS TR ICT SH O W IN G SU B C O U NTIES N Ky amuh ung a Ky abug im bi Kakanju N yab uba re Bushen yi-Ish aka TC Kyeizob a Bum baire 10 0 10 20 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....…….3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….…………...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Bushenyi district………….………...5 2- Map of Uganda showing Bushenyi district………..………………….………...……...14 10- Map of Bushenyi district showing sub counties………..………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Bushenyi district by sub counties…….....15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Bushenyi district…………………………………….……….…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create. -

3. AMON DISSERTATION.Pdf

KNOWLEDGE ABOUT STIGMA AMONG PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS CASE STUDY OF ISHAKA ADVENTIST HOSPITAL BUSHENYI-ISHAKA MUNICIPALITY- BUSHENYI DISTRICT BY NIWAMANYA AMON DCM/0031/143/DU A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO SCHOOL OF ALLIED HEALTH SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DIPLOMA IN CLINCAL MEDICINEAND COMMUNITY HEALTH AT KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY WESTERN CAMPUS JULY 2017 DECLARATION I declare that this research dissertation is my own work and it has never been presented to any university or any other institution for any award or qualification whatsoever. Where the work of other people has been included, acknowledgement to this has been made in accordance to the text and preferences. This study has never been submitted before for either publication or award of any kind. NIWAMANYA AMON (DCM/0031/143/DU) SIGNATURE:………………………………………. DATE……………………………………………….. i APPROVAL This research dissertation has been produced under my close supervision and I therefore recommend the student for presentation. SUPERVISOR: TASHOBYA DANIEL KAMUGISHA SIGNATURE:…………………………………………….. DATE……………………………………………………… ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work first to the almighty God who has helped me through this far and also to my parents, Mr. Byamukama Patrick and Mrs. Mwebesa Loy for their endless support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I highly acknowledge the almighty god whose strength and wisdom have helped me immeasurably towards completing this work. I would also like to acknowledge and appreciate the valuable contribution and support from my lecturer and supervisor Mr. Tashobya Daniel Kamugisha who has tirelessly guided me through my research. I am heavily indebted to my family who financially and psychologically made my studies possible.