Hadgekara.Pdf (1.9MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pluralism in Peril: Challenges to an American Ideal

PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL IDEAL AMERICAN AN TO CHALLENGES PERIL: IN PLURALISM PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL Report of the Inclusive America Project Report of the Inclusive America Project the Report Inclusive of January 2018 • Washington, D.C. Steven D. Martin – National Council of Churches THE ASPEN INSTITUTE JUSTICE AND SOCIETY PROGRAM 11-024 PLURALISM IN PERIL: CHALLENGES TO AN AMERICAN IDEAL Report of the Inclusive America Project January 2018 • Washington, D.C. Meryl Justin Chertoff Executive Editor Allison K. Ralph Editor The ideas and recommendations contained in this report should not be taken as representing the views or carrying the endorsement of the organization with which the author is affiliated. The organizations cited as examples in this report do not necessarily endorse the Inclusive America Project or its aims. For all inquiries related to the Inclusive America Project, please contact: Zeenat Rahman Project Director, Inclusive America Project [email protected] Copyright © 2018 by The Aspen Institute The Aspen Institute 2300 N Street, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20037 Published in the United States of America in 2018 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 18/001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ..............................................v Executive Editor’s Note .........................................vii Letter to the Reader . ix Introduction ...................................................1 PART 1: EMERGING -

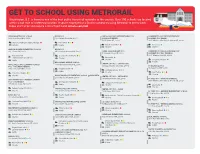

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

National Blue Ribbon Schools Recognized 1982-2015

NATIONAL BLUE RIBBON SCHOOLS PROGRAM Schools Recognized 1982 Through 2015 School Name City Year ALABAMA Academy for Academics and Arts Huntsville 87-88 Anna F. Booth Elementary School Irvington 2010 Auburn Early Education Center Auburn 98-99 Barkley Bridge Elementary School Hartselle 2011 Bear Exploration Center for Mathematics, Science Montgomery 2015 and Technology School Beverlye Magnet School Dothan 2014 Bob Jones High School Madison 92-93 Brewbaker Technology Magnet High School Montgomery 2009 Brookwood Forest Elementary School Birmingham 98-99 Buckhorn High School New Market 01-02 Bush Middle School Birmingham 83-84 C.F. Vigor High School Prichard 83-84 Cahaba Heights Community School Birmingham 85-86 Calcedeaver Elementary School Mount Vernon 2006 Cherokee Bend Elementary School Mountain Brook 2009 Clark-Shaw Magnet School Mobile 2015 Corpus Christi School Mobile 89-90 Crestline Elementary School Mountain Brook 01-02, 2015 Daphne High School Daphne 2012 Demopolis High School Demopolis 2008 East Highland Middle School Sylacauga 84-85 Edgewood Elementary School Homewood 91-92 Elvin Hill Elementary School Columbiana 87-88 Enterprise High School Enterprise 83-84 EPIC Elementary School Birmingham 93-94 Eura Brown Elementary School Gadsden 91-92 Forest Avenue Academic Magnet Elementary School Montgomery 2007 Forest Hills School Florence 2012 Fruithurst Elementary School Fruithurst 2010 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 96-97 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 2008 1 of 216 School Name City Year Grantswood Community School Irondale 91-92 Guntersville Elementary School Guntersville 98-99 Heard Magnet School Dothan 2014 Hewitt-Trussville High School Trussville 92-93 Holtville High School Deatsville 2013 Holy Spirit Regional Catholic School Huntsville 2013 Homewood High School Homewood 83-84 Homewood Middle School Homewood 83-84, 96-97 Indian Valley Elementary School Sylacauga 89-90 Inverness Elementary School Birmingham 96-97 Ira F. -

A Tale of Two Systems: Education Reform in Washington D.C

A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. 2 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE 3 A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Osborne would like to thank the Walton Family Foundation and the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation for their support of this work. He would also like to thank the dozens of people within D.C. Public Schools, D.C.’s charter schools, and the broader education reform community who shared their experience and wisdom with him. Thanks go also to those who generously took the time to read drafts and provide feedback. Finally, David is grateful to those at the Progressive Policy Institute who contributed to this report, including President Will Marshall, who provided editorial guidance, intern George Beatty, who assisted with research, and Steven K. Chlapecka, who shepherded the manuscript through to publication. 4 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................. ii A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. HISTORY AND CONTEXT.............................................................. 1 MICHELLE RHEE BRINGS IN HER BROOM .................................................. 4 THE POLITICAL -

A1. Ballou High School

A1. Ballou High School Contains Confidential Information ALVAREZ & MARSAL 2011 District of Columbia Comprehensive Assessment System Test Security Investigation School Summary Report CONTAINS CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION BALLOU HIGH SCHOOL I. IDENTIFYING INFORMATION School Name Ballou High School School Address 3401 4th St. SE Date Interviews Conducted March 27, 2012 and April 11, 2012 II. CLASSROOM FLAG INFORMATION Testing Accommodation Flagged By Flag No. Teacher Grade Reported DCPS OSSE 1 Mortimer 10th Yes X III. INTERVIEWS SCHEDULED AND CONDUCTED 2011 Testing Interview Interview Name Current Position Role/Position Location Conducted Rahman Branch Principal Oversight School Yes Academy Coordinator at Eastern High Testing Eastern High Kimberly Farley School Coordinator School Yes (4/11/12) Monique Peterson Assistant Principal Oversight School Yes English Teacher, Test Melissa Mortimer 10th Grade Administrator School Yes No – at a Mr. Chandra Teacher Proctor School conference Test Jeremy Crouthamel Teacher Administrator School Yes Student, 11th Whitney Henry Grade Student School Yes Student, 11th Timisha Ray Grade Student School Yes - 2 - Contains Confidential Information IV. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS Our investigation process at Ballou HS included seven interviews and a document review. We conducted a follow-up interview with the Test Coordinator, Kimberly Farley on April 11, 2012, who recently transferred to another school (Eastern). The 2011 Test Security Binder was found to be organized and complete. The administrator of the flagged classroom, Ms. Mortimer, is regarded by students and the administration to be one of the school’s most effective teachers. We found no evidence to indicate that s/he violated DC CAS testing guidelines. S/he taught 10th grade honor students, and started preparing for the 2011 DC CAS test in November (four months before the test) while most of the other teachers started in January. -

What's in a Name

What’s In A Name: Profiles of the Trailblazers History and Heritage of District of Columbia Public and Public Charter Schools Funds for the DC Community Heritage Project are provided by a partnership of the Humanities Council of Washington, DC and the DC Historic Preservation Office, which supports people who want to tell stories of their neighborhoods and communities by providing information, training, and financial resources. This DC Community Heritage Project has been also funded in part by the US Department of the Interior, the National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the DC Historic Preservation Office and by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240.‖ In brochures, fliers, and announcements, the Humanities Council of Washington, DC shall be further identified as an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. 1 INTRODUCTION The ―What’s In A Name‖ project is an effort by the Women of the Dove Foundation to promote deeper understanding and appreciation for the rich history and heritage of our nation’s capital by developing a reference tool that profiles District of Columbia schools and the persons for whom they are named. -

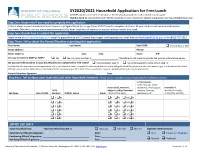

SY2020/2021 Household Application for Free Lunch All DCPS Students Receive Free Breakfast

SY2020/2021 Household Application for Free Lunch All DCPS students receive free breakfast. Select schools provide free afterschool snack/supper. Use this form to request free lunch for the students in your household. Submit 1 application per household/school year. Step One: Determine if you need to complete this application. If ALL students in your household attend a Community Eligible School (list on pg 2) you DO NOT need to complete this form. All your students will automatically receive free lunch. Otherwise, you are encouraged to complete this form, regardless of whether or not you want to receive free lunch. Step Two: Decide how to submit this application. Apply online at dcps.heartlandapps.com, bring this paper form to a DCPS school that accepts lunch applications, email forms to [email protected], or fax @202-727-2512 Step Three: Tell us about the Parent/Guardian submitting this application. First Name: Last Name: Last 4 SSN: ❑ I do not have a SSN Email address: Phone: Home Address: Apt: City: State: ZIP: Are you enrolled in SNAP or TANF? ❑ No ❑ Yes, my case number is: I therefore do not need to provide the income information below. Do you want the students in your household to be considered for free meals? ❑ Yes (complete step 4) ❑ No (write student’s name only in step 4) I certify that all information on this application is true and that all income is reported. I understand that the school will get Federal funds based on the information I give. I understand that school officials may verify the information. -

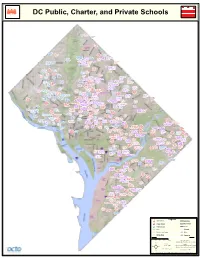

Legend Public Schools Interstates

DC Public, Charter, and Private Schools Shepherd Lowell Elementary School School San Miguel School Takoma Education Campus Blessed Sacrament Lafayette School Coolidge Roots Activity Elementary High School Learning School Jewish Primary Center Dat School of the Center City Bridges Ideal Hope Community St. John's Nation's Capital PCS-Brightwood Academy Whittier Academy PCS - Lamond College Campus Education PCS Campus High School Latin Campus American Montessori LaSalle-Backus KinderHaus Brightwood Paul PCS Monterssori Billingual (LAMB) Education School of of Chevy Education Community Campus Chevy Chase Chase Campus Academy PCS-Amos II Community Academy Roots PCS Online PCS Community Academy Truesdell PCS-RAND Deal Education Technology Campus Auguste Georgetown Middle Campus Montessori West Day School School Mamie D. Education High School Kingsbury Lee School Campus Murch Day School Wilson Elementary High Barnard Janney School Franklin School Parkmont Elementary Elementary Montessori School School School St. Ann's Sheridan School E.L. Haynes PCS Kennedy Institute Academy School Community - Kansas Avenue E.L. Haynes PCS - of Catholic St. Anselm's Academy (Grades PK3-2) Kansas Avenue (Grade 9) Charities Abbey School Amazing PCS-Amos I MacFarland Potomac Edmund Life Games Center City National Middle School PCS Petworth Lighthouse Washington Brookland Burke Preschool PCS Yu Ying PCS Education Campus Presbyterian Hearst Campus Archbishop School Hospitality High @ Bunker Hill School Elementary Roosevelt STAY Carroll Sidwell School PCS Inspired -

Speaker Biographies

Speaker Biographies Michelle Johnson Armstrong has been with the US Department of Education for more than 15 years. She has managed and worked on several discretionary grant programs focusing on school choice, the arts, and teachers’ professional development. She brings expertise on program analysis and evaluation focused on evidence-based community efforts for planning and implementation and educational outcomes affecting school-age children. Before coming to the US Department of Education, Armstrong worked on evidence-based evaluation projects in Ithaca, New York, while completing her graduate studies at Cornell University. Melodie Baker is gaining attention as one of the nation’s most promising leaders. Shortly after starting her own independent research-based evaluation firm, Q&A STATS LLC, this past February she was awarded the contract to lead New York state’s First 1,000 Days Medicaid reform efforts in partnership with the Rockefeller Institute for Government and the Pritzker Foundation. Baker is also the director of education at the United Way of Buffalo and Erie County, cochair of the United Way Community Schools Learning Community, cochair of RaisingNY, and chair of the Erie-Niagara Birth to 8 Coalition. In 2014, she cofounded the Charter School of Inquiry, the first inquiry-based school in Western New York. Baker has spent the last 14 years of her career working to expand opportunities for the most vulnerable and underserved people. She has demonstrated her work on national platforms and was the keynote speaker for the US Department of Education’s National Promise Neighborhoods Conference in Washington, DC, in October 2018. Baker has received numerous recognitions, including Buffalo Niagara Partnership’s 2017 Athena Young Professional Leadership Award and Nasdaq and EverFi’s Education Innovation Award. -

Food System Assessment

FOOD SYSTEM ASSESSMENT The District’s efforts to support a more equitable, healthy, and sustainable food system 2018 Published Spring 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE MAYOR OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA.................................................................. 3 LETTER FROM THE DC FOOD POLICY DIRECTOR .....................................................................................................4 DISTRICT AGENCY ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY AND DATA COLLECTION .......................................................................................................................... 6 OVERVIEW OF THE FOOD ASSESSMENT..................................... ........................................................... 7 OVERVIEW OF THE DISTRICT’S FOOD SYSTEM GOALS AND PRIORITIES..................................... 8 SECTION 1: IMPROVING FOOD SECURITY AND HEALTH IN THE DISTRICT FOOD INSECURITY .......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 FOOD INSECURITY AND HEALTH ..............................................................................................................................................................................11 FEDERAL NUTRITION ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................................................ -

School-Based Health Programs

January 2017 Children’s National School-Based Health Programs Environmental Scan and Recommendations Report Prepared by the Child Health Advocacy Institute Community Aairs Department Acknowledgments The Child Health Advocacy Institute would like to extend our appreciation to everyone who contributed to this report. We could not have gathered this information without support and guidance from many dedicated individuals across Children’s National Health System. To staff members who contributed to this report, thank you for your dedication and support for our children. Your willingness to share and connect has been a tremendous asset and we look forward to continued collaboration. Julia DeAngelo, Program Manager of School Strategies, led the stakeholder interview, analysis, and report writing with substantive direction and input from Desiree de la Torre, Director of Community Affairs and Population Health. Cynthia Adams, Community Education Specialist, supported the stakeholder interview process and contributed to the report. Danielle Dooley, Medical Director of Community Affairs and Population Health, and Chaya Merrill, Director of the Child Health Data Lab edited the report. Penelope Theodorou, Program Coordinator for the Early Childhood Innovation Network, contributed to the report layout and design. The recommendations and conclusion expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions of our collaborators. Disclaimer This report is a compendium of current and prior school-based programs sponsored by Children’s National for which information could be captured. Our environmental scan gathered input broadly from all stakeholders who participate in school-based programs across the hospital system; however, stakeholders who were interviewed did not always have all of the relevant program information and a few stakeholders could not be reached to provide feedback on a drafted school program summary.