Pluralism in Peril: Challenges to an American Ideal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRUMP Can't Let GO of Perceived Slights

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 3, 2016 ANALYSIS THE LEADING INDEPENDENT DAILY IN THE ARABIAN GULF ESTABLISHED 1961 Founder and Publisher YOUSUF S. AL-ALYAN Editor-in-Chief ABD AL-RAHMAN AL-ALYAN EDITORIAL : 24833199-24833358-24833432 ADVERTISING : 24835616/7 FAX : 24835620/1 CIRCULATION : 24833199 Extn. 163 ACCOUNTS : 24835619 COMMERCIAL : 24835618 P.O.Box 1301 Safat,13014 Kuwait. E MAIL :[email protected] Website: www.kuwaittimes.net Washington Watch Didi’s dominance over Uber offers roadmap for rivals By Brad Brooks hina ride-hailing service Didi Chuxing’s domi- nance of Uber Technologies in the China market Cmay provide a playbook for regional rivals to fend off the biggest US ride-hailing company, especially in Southeast Asia and India. The two companies on Monday confirmed the sale of Uber China to its bigger rival, ending a two-year, money-losing effort to break into one of the world’s toughest markets. Uber leaves with around a one-fifth stake in Didi, but will give up control of its China operations. Didi had a head start and maintained the lead on Uber with a strategy that other rivals may emulate, analysts and investors said. Didi counts two of the most powerful, best capital- ized Chinese Internet companies as backers; has tight connections with local government; made an ally of Trump can’t let go of perceived slights local taxi drivers and expanded into services such as buses that Uber ignored; and exploited its knowledge By Julie Pace awarded a Bronze Star and Purple Heart after his death in attacked” by Khizr Khan. Trump’s unwillingness to let the of local culture and consumers. -

Inside Islam Screening Kit – Copyright 2009-2010 Unity Productions Foundation

Inside Islam A UPF Documentary Film Based on the Gallup Poll of Worldwide Muslim Public Opinion Executive Producers: Michael Wolfe and Alex Kronemer Screening Kit Table of Contents Conducting A Screening in Your City Executive Summary 3 Models Examples to Follow 4 Criteria for Conducting a Screening 5 Recommendations 6 Sample Program 7 Budgeting Example Costs for Different Locations 8 Budget Breakdown 8 Raising Funds and Getting Sponsors Funds for the Screening 12 Getting Organizations on Board and Getting Sponsors 12 Slide for Sponsors in Slideshow 12 Ticket Sales Tips 13 UPF’s Role in the Screening What UPF Can Provide 13 Dates Available 13 Organizer Roles 14 FAQ’s 16 Review…Next Steps 17 Samples & Articles Publicity/Invitation 20 Sponsorship/Feedback Forms 22 Sample Press Release 24 Biographies of Possible Speakers from UPF 28 2 Inside Islam Screening Kit – Copyright 2009-2010 Unity Productions Foundation www.upf.tv 3 Inside Islam Screening Kit – Copyright 2009-2010 Unity Productions Foundation www.upf.tv Conducting a Screening in Your City Executive Summary This ‘Screening Kit’ will take you through the process of planning a screening for UPF’s Inside Islam film in your city. Simply put, a ‘screening’ is a showing of the film to a live audience, which typically takes place in a proper theater and often features a speaker associated with the film. Screenings also feature a reception before or afterward. Conducting a screening is a way of bringing the community together, and building bridges across racial and religious lines, thus promoting UPF’s mission. It’s also a celebration of a completed project and a way of rewarding you and the supporters in your area who have helped make this project a reality. -

Cheers and Jeers: Left Behind

Cheers and Jeers: Left behind Marty Trillhaase/Lewiston Tribune JEERS ... to Idaho Gov. C.L. "Butch" Otter. His decision to replace Bill Goesling of Moscow with Albertsons executive Andrew Scoggin of Boise leaves north central Idaho the odd man out on the State Board of Education. The governor is under no legal obligation to maintain a geographical balance on the state board. But certainly that's been the practice. In fact, someone from Latah County has served on the state board since 1991, when then-Gov. Cecil D. Andrus appointed attorney Roy Mosman. In 1998, Gov. Phil Batt replaced an ailing Mosman with former House Speaker Tom Boyd, R-Genesee. Three years later, Gov. Dirk Kempthorne appointed former Moscow Mayor Paul Agidius. And five years ago, Otter selected Goesling. Geography is not destiny. For instance, there is no more ardent advocate for the University of Idaho than state board President Emma Atchley of Ashton, a former president of the UI Foundation. Still, of the seven people Otter has named to the state board, three - former West Ada School Superintendent Linda Clark and former Idaho National Laboratory Deputy Director David Hill and now Scoggin - are from Ada County. That leaves just one northerner - Don Soltman of Twin Lakes, north of Coeur d'Alene - on the state board. This involves a vast area running from the Ada County line to Worley. It encompasses two of Idaho's four institutions of higher learning. Why is Otter ignoring it? JEERS ... to Otter, again. The governor has a bad habit. Rather than rely on Attorney General Lawrence Wasden's staff, Otter prefers to burn through hundreds of thousands of dollars hiring outside counsel. -

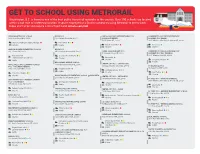

GET to SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C

GET TO SCHOOL USING METRORAIL Washington, D.C. is home to one of the best public transit rail networks in the country. Over 100 schools are located within a half mile of a Metrorail station. If you’re employed at a District school, try using Metrorail to get to work. Rides start at $2 and require a SmarTrip® card. wmata.com/rail AIDAN MONTESSORI SCHOOL BRIYA PCS CARLOS ROSARIO INTERNATIONAL PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 2700 27th Street NW, 20008 100 Gallatin Street NE, 20011 (SONIA GUTIERREZ) ACADEMY PCS (MAIN) 514 V Street NE, 20002 2405 Martin Luther King Jr Avenue SE, 20020 Woodley Park-Zoo Adams Morgan Fort Totten Private Charter Rhode Island Ave Anacostia Charter Charter AMIDON-BOWEN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL BRIYA PCS 401 I Street SW, 20024 3912 Georgia Avenue NW, 20011 CEDAR TREE ACADEMY PCS COMMUNITY COLLEGE PREPARATORY 701 Howard Road SE, 20020 ACADEMY PCS (MC TERRELL) Waterfront Georgia Ave Petworth 3301 Wheeler Road SE, 20032 Federal Center SW Charter Anacostia Public Charter Congress Heights BROOKLAND MIDDLE SCHOOL Charter APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 1150 Michigan Avenue NE, 20017 CENTER CITY PCS - CAPITOL HILL PCS - COLUMBIA HEIGHTS 1503 East Capitol Street SE, 20003 DC BILINGUAL PCS 2750 14th Street NW, 20009 Brookland-CUA 33 Riggs Road NE, 20011 Stadium Armory Public Columbia Heights Charter Fort Totten Charter Charter BRUCE-MONROE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL @ PARK VIEW CENTER CITY PCS - PETWORTH 3560 Warder Street NW, 20010 510 Webster Street NW, 20011 DC PREP PCS - ANACOSTIA MIDDLE APPLETREE EARLY LEARNING CENTER 2405 Martin Luther -

Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think

Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think Teaching Guide John L. Esposito and Dalia Mogahed Gallup Press This document contains proprietary research, copyrighted materials, and literary property of Gallup, Inc. It is for the guidance of your company‟s executives only and is not to be copied, quoted, published, or divulged to others ® ® outside of your organization. Gallup and The Gallup Poll are trademarks of Gallup, Inc. A Teaching Guide for Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think Table of Contents About the Book ................................................................................................................................................ 3 About the Authors ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapters One — Five ................................................................................................................................. 3-10 Summary Important Findings Discussion Questions Thinking Critically Beyond the Book Comprehension Questions ........................................................................................................................... 10 Further Reading ........................................................................................................................................ 10-11 Copyright © 2008 Gallup, Inc. All rights reserved. 2 A Teaching Guide for Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think About the Book Are -

Hizb Ut-Tahrir Ideology and Strategy

HIZB UT-TAHRIR IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY “The fierce struggle… between the Muslims and the Kuffar, has been intense ever since the dawn of Islam... It will continue in this way – a bloody struggle alongside the intellectual struggle – until the Hour comes and Allah inherits the Earth...” Hizb ut-Tahrir The Centre for Social Cohesion Houriya Ahmed & Hannah Stuart HIZB UT-TAHRIR IDEOLOGY AND STRATEGY “The fierce struggle… between the Muslims and the Kuffar, has been intense ever since the dawn of Islam... It will continue in this way – a bloody struggle alongside the intellectual struggle – until the Hour comes and Allah inherits the Earth...” Hizb ut-Tahrir The Centre for Social Cohesion Houriya Ahmed & Hannah Stuart Hizb ut-Tahrir Ideology and Strategy Houriya Ahmed and Hannah Stuart 2009 The Centre for Social Cohesion Clutha House, 10 Storey’s Gate London SW1P 3AY Tel: +44 (0)20 7222 8909 Fax: +44 (0)5 601527476 Email: [email protected] www.socialcohesion.co.uk The Centre for Social Cohesion Limited by guarantee Registered in England and Wales: No. 06609071 © The Centre for Social Cohesion, November 2009 All the Institute’s publications seek to further its objective of promoting human rights for the benefit of the public. The views expressed are those of the author, not of the Institute. Hizb ut-Tahrir: Ideology and Strategy By Houriya Ahmed and Hannah Stuart ISBN 978-0-9560013-4-4 All rights reserved The map on the front cover depicts Hizb ut-Tahrir’s vision for its Caliphate in ‘Islamic Lands’ ABOUT THE AUTHORS Houriya Ahmed is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Social Cohesion (CSC). -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

We Appreciate Your Support of WEST! Thank You for Your Partnership in Getting the Word out About Our Programs

Having trouble viewing this email? Click here We appreciate your support of WEST! Thank you for your partnership in getting the word out about our programs. We ask that you continue to support us and post our upcoming programs on your calendars and spread the word about our very exciting upcoming events. If you have any events you would like us to include in our newsletter we would be happy to include them. Warmest regards, Ilene Fischer Executive Director WEST Advancing Women in the Business of Science and Technology office: 617.682.3702 cell: 603.566.0299 www.westorg.org WEST Announces Leadership for Societal Impact Awardees WEST is proud to announce today the three Leadership for Societal Impact Awardees: Toni Wolfman, the first women partner at Foley Hoag who supported WEST from its inception, supported the Boston Club and the Commonwealth Institute, currently is a leader at Bentley's center for Women and Business. Read her bio HERE Yvonne Spicer - VP at the Museum of Science she advocates for the Museum's K-12 curricula, Engineering is Elementary, Building Math, and Engineering the Future, and she directs the Gateway Project, which originated in Massachusetts and is being replicated across the U.S. as a model to build leadership capacity for technological literacy. Read her bio HERE Vanessa Kerry - Vanessa Kerry is the founder and CEO of Global Health Service Corps, a non-profit that partners with the Peace Corps to build capacity of developing country health systems by deploying health professionals as educators. She is also a physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. -

National Blue Ribbon Schools Recognized 1982-2015

NATIONAL BLUE RIBBON SCHOOLS PROGRAM Schools Recognized 1982 Through 2015 School Name City Year ALABAMA Academy for Academics and Arts Huntsville 87-88 Anna F. Booth Elementary School Irvington 2010 Auburn Early Education Center Auburn 98-99 Barkley Bridge Elementary School Hartselle 2011 Bear Exploration Center for Mathematics, Science Montgomery 2015 and Technology School Beverlye Magnet School Dothan 2014 Bob Jones High School Madison 92-93 Brewbaker Technology Magnet High School Montgomery 2009 Brookwood Forest Elementary School Birmingham 98-99 Buckhorn High School New Market 01-02 Bush Middle School Birmingham 83-84 C.F. Vigor High School Prichard 83-84 Cahaba Heights Community School Birmingham 85-86 Calcedeaver Elementary School Mount Vernon 2006 Cherokee Bend Elementary School Mountain Brook 2009 Clark-Shaw Magnet School Mobile 2015 Corpus Christi School Mobile 89-90 Crestline Elementary School Mountain Brook 01-02, 2015 Daphne High School Daphne 2012 Demopolis High School Demopolis 2008 East Highland Middle School Sylacauga 84-85 Edgewood Elementary School Homewood 91-92 Elvin Hill Elementary School Columbiana 87-88 Enterprise High School Enterprise 83-84 EPIC Elementary School Birmingham 93-94 Eura Brown Elementary School Gadsden 91-92 Forest Avenue Academic Magnet Elementary School Montgomery 2007 Forest Hills School Florence 2012 Fruithurst Elementary School Fruithurst 2010 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 96-97 George Hall Elementary School Mobile 2008 1 of 216 School Name City Year Grantswood Community School Irondale 91-92 Guntersville Elementary School Guntersville 98-99 Heard Magnet School Dothan 2014 Hewitt-Trussville High School Trussville 92-93 Holtville High School Deatsville 2013 Holy Spirit Regional Catholic School Huntsville 2013 Homewood High School Homewood 83-84 Homewood Middle School Homewood 83-84, 96-97 Indian Valley Elementary School Sylacauga 89-90 Inverness Elementary School Birmingham 96-97 Ira F. -

A Tale of Two Systems: Education Reform in Washington D.C

A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. 2 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. BY DAVID OSBORNE PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE 3 A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Osborne would like to thank the Walton Family Foundation and the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation for their support of this work. He would also like to thank the dozens of people within D.C. Public Schools, D.C.’s charter schools, and the broader education reform community who shared their experience and wisdom with him. Thanks go also to those who generously took the time to read drafts and provide feedback. Finally, David is grateful to those at the Progressive Policy Institute who contributed to this report, including President Will Marshall, who provided editorial guidance, intern George Beatty, who assisted with research, and Steven K. Chlapecka, who shepherded the manuscript through to publication. 4 PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................. ii A TALE OF TWO SYSTEMS: EDUCATION REFORM IN WASHINGTON D.C. HISTORY AND CONTEXT.............................................................. 1 MICHELLE RHEE BRINGS IN HER BROOM .................................................. 4 THE POLITICAL -

October 2016 the Head of the Charles Continued on Page 24

The RegisterRegister ForumForum Established 1891 Vol. 129, No. 2 Cambridge Rindge and Latin School October 2016 The Head of the Charles Continued on page 24 Three Rindge boats raced in the 52nd Head of the Charles; the Varsity Boys boats came in 19th and 66th and the Varsity Girls came in 22nd place. Photo Credit: Cam Poklop For Rindge, It’s No Contest Cambodian Genocide In RF Mock Election Hillary Wins Handily Survivor Speaks at CRLS nominee for president. ge students are not a fan eight years old to fight in By By All together, 14.4% of of the Twenty-Second Am- a war. In the middle of the Diego Lasarte Kiana Laws students, unprompted, re- mendment, as 1.8% of the war, Pond fled to the jungle Register Forum Register Forum Staff fused to pick one of the four student body—fifth place— Editor-in-Chief and later found himself in a major candidates or to ab- wrote in President Obama, In 1975, after the Viet- Thai refugee camp. Soon he After surveying al- stain and instead wrote in a wanting a third term for the nam war, the Khmer Rouge was found by Peter Pond, an most one fourth of CRLS candidate of their choosing. sitting president. took over Cambodia. They American man who later ad- students, teachers, and After Senator Sanders, However, President promised to bring peace opted him and brought him staff, the Register Forum is Republican nominee Don- Obama was not the only back to their country, but to America. prepared to announce that ald Trump and Libertarian write-in ineligible for the instead they starved and In America, he went Democratic nominee Sec- nominee Governor Gary office of the presidency: re- abused millions of Cambo- to highschool, but things retary Clinton has cently martyered dians, wiping out almost all were still very difficult for won the Rindge gorilla Harambe of their music him. -

& Population Orld Health

ORLD HEALTH & POPULATION www.worldhealthandpopulation.com • Volume 16 • Number 1 THEME The Global Health Workforce: Striving for Equity ISSUE Tackling Challenges on the Ground Health Workforce Measurement: Seeking Global Governance and National Accountability Improving Access to Care among Underserved Populations: The Role of Health Workforce Data in Health Workforce Policy, Planning and Practice Global Perspectives on Nursing and Its Contribution to Healthcare and Health Policy: Thoughts on an Emerging Policy Model A LONGWOODS PUBLICATION W ORLD HEALTH & POPULATION IN THIS ISSUE Volume 16 • Number 1 FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Judith Shamian 3 FROM THE GUEST EDITOR – Delivering on Equity Depends on Us Marilyn A. DeLuca 4 COMMENTARY – Time for a Copernican Revolution in Health Labour Markets Agnes Soucat 6 RESEARCH PAPERS Health Workforce Measurement: Seeking Global Governance and National Accountability Marilyn A. DeLuca and Sofia Castro Lopes 8 Global Health Service Partnership: First Year Findings Vanessa Kerry, Libby Cunningham, Pat Daoust and Sadath Sayeed 24 Improving Access to Care among Underserved Populations: The Role of Health Workforce Data in Health Workforce Policy, Planning and Practice Jennifer Wesson, Pamela McQuide, Claire Viadro, Maritza Titus, Norbert Forster, Daren Trudeau and Maureen Corbett 36 Health Human Resources: A Critical yet Challenging Pathway to Universal Health Coverage in Indonesia Rosalia Sciortino and Roy Tjong 51 Thai Health Promotion Foundation: Innovative Enabler for Health Promotion Sakol Sopitarchasak, Supreda Adulyanon and Tananart Lorthong 62 Findings from a Survey of an Uncategorized Cadre of Clinicians in 46 Countries Nadia Cobb, Marie Meckel, Jennifer Nyoni, Karen Mulitalo, Hoonani Cuadrado, Jeri Sumitani, Gerald Kayingo and David Fahringer 72 The Effect of the Conflict on Syria’s Health System and Human Resources for Health Aula Abbara, Karl Blanchet, Zaher Sahloul, Fouad Fouad, Adam Coutts and Wasim Maziak 87 REPRINT – Nursing Leadership.