A Universalist History of the 1987 Philippine Constitution (I)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

TRANSLATING VERNACULAR CULTURE the Case of Ramon Muzones's Shri-Bishaya

Journal of English Studies and Comparative Literature TRANSLATING VERNACULAR CULTURE The Case of Ramon Muzones’s Shri-Bishaya Ma. Cecilia Locsin-Nava Every group of people makes an appeal to the past for its sense of cultural identity and its preferred trajectory for the future. However, the past is never accessible without translation, even within the same language. - K.W. Taylor No body of writing in Western Visayan literature has attracted as much attention, controversy, and translation as Monteclaro’s Maragtas. It was written by Don Pedro Monteclaro, the first municipal president of Miag-ao, Iloilo, local historian, and war hero in a mixture of Kinaray-a and Hiligaynon in 1901 at the end of the Filipino-American war when Ilonggos lost, all too soon, their hard-won independence from Spain to the Americans. However, it did not get published until 1907 in Kadapig sa Banwa (Ally of the Country), a nationalist newspaper in Iloilo city. By then, the zeitgeist of frustrated nationalism was finding expression in a number of nativist movements that sought to “revive and revalue” local language and culture. Significantly, reacting to “the privileging of the imported over the indigenous, English over local languages; writing over orality and linguistic culture over inscriptive culture,” (Ashcroft Griffiths and Tiffin 1983: 64) several advocacy groups were established. The first is Academia Bisaya (1901), established by regional writers and 60 Journal of English Studies and Comparative Literature journalists to promote among others, linguistic purism. Next, the standardization of Hiligaynon orthography and usage was promoted in order to protect it from further distortions introduced by Spanish friars, literary societies or talapuanan. -

THE SPANISH-DEFINED SEPARATISMO in TAAL, 1895-96: a Prologue to a Revolution

THE SPANISH-DEFINED SEPARATISMO IN TAAL, 1895-96: A Prologue to a Revolution by Manuelito M. Recto In 1895, in the town of Taal, province of Batangas, the Spanish local authorities worked hard enough to denounce some of its inhabitants as subversiVe. They defined the objective of the Taal subversives as the promotion and instigation of anti-patriotic ideas and propaganda against religion to inculcate in the minds of the inhabitants of Batangas the existence of a subversive separatist idea. These ''se paratists", led by Felipe Agoncillo and followed by Ramon Atienza, Martin Cabre ra, Ananias Diocno and many others, were persecuted for manifesting outwardly their nurtured ideas whtch were allegedly in complete opposition to the precepts of the Spanish constitution and ecclesiastical Jaws. Episode 1: 1895 Subversion On July 23, 1895, a report was transmitted by the parish priest of Taal, Fr. julian Diez, to his superior, Archbishop Bernardino Nozaleda, regarding the latest occurrence in that town. Here, he said, things had happened as a result of certain doctrines and certain personalities, that his loyalty to religion and his beloved Spain had forced him to write the prelate before anyone else. He stated that on 65 66 ASIAN STUDIES June 24, during the interment of a ::laughter of Felipe Agoncillo at the Taal cemetery, Agoncillo spoke offensive words against Spain and its religion after the parish priest refused to have the corpse buried in an untaxed coffin. Fr. Diez attributed to Agoncillo these statements) What I have l8id to you always, (is) that religion is a lie, a despicable farce that we do not have anymore remedy but to swallow it for it was imposed to us by the poorest and most miserable nation of all Europe. -

Reproductive Health Bill

Reproductive Health Bill From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Intrauterine device (IUD): The Reproductive Health Bill provides for universal distribution of family planning devices, and its enforcement. The Reproductive Health bills, popularly known as the RH Bill , are Philippine bills aiming to guarantee universal access to methods and information on birth control and maternal care. The bills have become the center of a contentious national debate. There are presently two bills with the same goals: House Bill No. 4244 or An Act Providing for a Comprehensive Policy on Responsible Parenthood, Reproductive Health, and Population and Development, and For Other Purposes introduced by Albay 1st district Representative Edcel Lagman, and Senate Bill No. 2378 or An Act Providing For a National Policy on Reproductive Health and Population and Development introduced by Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago. While there is general agreement about its provisions on maternal and child health, there is great debate on its key proposal that the Philippine government and the private sector will fund and undertake widespread distribution of family planning devices such as condoms, birth control pills(BCPs) and IUDs, as the government continues to disseminate information on their use through all health care centers. The bill is highly divisive, with experts, academics, religious institutions, and major political figures supporting and opposing it, often criticizing the government and each other in the process. Debates and rallies for and against the bill, with tens of thousand participating, have been happening all over the country. Background The first time the Reproductive Health Bill was proposed was in 1998. During the present 15th Congress, the RH Bills filed are those authored by (1) House Minority Leader Edcel Lagman of Albay, HB 96; (2) Iloilo Rep. -

DOLOR DE MIS DOLORES* a Position Paper on Parliamentary Bill No. 195 REMIGIO E. AGPALO** First of All, I Would Like T

FILIPINAS: DOLOR DE MIS DOLORES* A Position Paper on Parliamentary Bill No. 195 REMIGIO E. AGPALO** First of all, I would like to exp~ess my gratitude to the Chair man of the Sub-Committee on Constitutional Law for inviting me to present my views on the important issue of whether we should change the name PHILIPPINES to MAHARLIKA as provided in Parliamentary Bill No. 195. My position on this important question may be divided into two parts - a comment on matters I regard as secondary and a pre sentation of my main argument. The principal argument involves the problem of the crisis of identity, one of the major crises which confront all developing or modernizing countries. I shall discuss this in Section Ill of this paper after I have considered the secondary matters. I adopt this approach because the main argument ought to be discussed last in order to give it the emphasis it deserves. II Let me, then, begin with the secondary matters, which are embodied in the argument of the proponent of Parliamentary Bill No. 195: ( 1) That the name Philippines "merely reflects the victories of our invaders," for the Spaniards named our country "after Philip II of Spain" (Parliamentary Bill No. 195); (2) That the Philippines, named after Philip II, connotes the bad or even the worst that could be said concerning man, for Philip II was "a monster of bigotry, ambition, lust, and cruelty;" "ignoble in life as well as in death"1; and (3) That several countries of the Third World, such as the Gold Coast, Congo, and Northern Rhodesia have changed their names to Ghana, Zaire, and Zambia, respectively, in order to cast off taints of colonialism. -

In Pursuit of Genuine Gender Equality in the Philippine Workplace

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 6-2013 Neither a Pedestal nor a Cage: In Pursuit of Genuine Gender Equality in the Philippine Workplace Emily Sanchez Salcedo Maurer School of Law - Indiana University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/etd Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Salcedo, Emily Sanchez, "Neither a Pedestal nor a Cage: In Pursuit of Genuine Gender Equality in the Philippine Workplace" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 80. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/etd/80 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEITHER A PEDESTAL NOR A CAGE: IN PURSUIT OF GENUINE GENDER EQUALITY IN THE PHILIPPINE WORKPLACE Emily Sanchez Salcedo Submitted to the faculty of Indiana University Maurer School of Law in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Juridical Science June 2013 Accepted by the faculty, Indiana University Maurer School of Law, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science. Doctoral Committee /.,' /.------·-···,v~··- \ .?f:-,. ,. '.:CL ./. ,,,, j ·,..-c..-J'1!""-t~".c -- -...;;;~_, .- <.. r __ I'""=-,.,. __ .,.~·'--:-; Prof. Susan H. Williams ~ l - Prof. Deborah A. Widiss ~l Prof. Dawn E. Johnsen May 24, 2013 ii Copyright© 2013 Emily Sanchez Salcedo iii ACKNOWLEDGMENT This work would not have been possible without the generous support extended by The Fulbright Program, American Association of University Women, Delta Kappa Gamma Society International, De La Salle University - Mme. -

A HISTORY of SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY in the PHILIPPINES by Olivia C

GE1713 A HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE PHILIPPINES by Olivia C. Caoili** Introduction The need to develop a country's science and technology has generally been recognized as one of the imperatives of socioeconomic progress in the contemporary world. This has become a widespread concern of governments especially since the post world war 11 years.1 Among Third World countries, an important dimension of this concern is the problem of dependence in science and technology as this is closely tied up with the integrity of their political sovereignty and economic self-reliance. There exists a continuing imbalance between scientific and technological development among contemporary states with 98 per cent of all research and development facilities located in developed countries and almost wholly concerned with the latter's problems2 Dependence or autonomy in science and technology has been a salient issue in conferences sponsored by the United Nations.3 It is within the above context that this paper attempts to examine the history of science and technology in the Philippines. Rather than focusing simply on a straight chronology of events, it seeks to interpret and analyze the interdependent effects of geography, colonial trade, economic and educational policies and socio-cultural factors in shaping the evolution of present Philippine science and technology. As used in this paper, science is concerned with the systematic understanding and explanation of the laws of nature. Scientific activity centers on research, the end result of which is the discovery or production of new knowledge.4 This new knowledge may or may not have any direct or immediate application. -

THE PHILJA JUDICIAL JOURNAL Inspirational Messages from the Bench

THE PHILJA JUDICIAL JOURNAL Inspirational Messages From The Bench January - December 1999 OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2000 Vol. 2, Issue No. 6 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. HILARIO G. DAVIDE, Jr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. JOSUE N. BELLOSILLO Hon. JOSE A.R. MELO Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO Hon. JOSE C. VITUG Hon. SANTIAGO M. KAPUNAN Hon. VICENTE V. MENDOZA Hon. ARTEMIO V. PANGANIBAN Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. FIDEL P. PURISIMA Hon. BERNARDO P. PARDO Hon. ARTURO B. BUENA Hon. MINERVA GONZAGA REYES Hon. CONSUELO YÑARES-SANTIAGO Hon. SABINO R. DE LEON COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. ALFREDO L. BENIPAYO DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. REYNALDO L. SUAREZ Hon. ZENAIDA N. ELEPAÑO Hon. BERNARDO T. PONFERRADA CLERK OF COURT Attorney LUZVIMINDA D. PUNO ASST. COURT ADMINISTRATORS Attorney ANTONIO H. DUJUA Attorney JOSE P. PEREZ Attorney ISMAEL G. KHAN, Jr. (Chief, Public Information Office) ASST. CLERK OF COURT Attorney MA. LUISA D. VILLARAMA DIVISION CLERKS OF COURT Attorney VIRGINIA A. SORIANO Attorney TOMASITA M. DRIS Attorney JULIETA Y. CARREON PHILIPPINE JUDICIAL ACADEMY Board of Trustees Hon. HILARIO G. DAVIDE Jr. Chief Justice Chairman Hon. JOSUE N. BELLOSILLO Senior Associate Justice, Supreme Court Vice-Chairman Members Hon. AMEURFINA A. MELENCIO HERRERA Hon. ALFREDO L. BENIPAYO Chancellor Court Administrator Hon. SALOME A. MONTOYA Hon. FRANCIS E. GARCHITORENA Presiding Justice, Court of Appeals Presiding Justice, Sandiganbayan Hon. DANILO B. PINE Dean HERNANDO B. PEREZ President, Philippine Judges Association President, Philippine Association of Law Schools Executive Officials Hon. AMEURFINA A. MELENCIO HERRERA Chancellor Hon. ANTONIO M. MARTINEZ Vice-Chancellor Hon. PRISCILA S. AGANA Executive Secretary Attorney EDWIN R. -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

The 'Unfinished Revolution' in Philippine Political Discourse

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 31, No. I, June 1993 The 'Unfinished Revolution' in Philippine Political Discourse Reynaldo C. ILETo * The February 1986 event that led to Marcos's downfall is usually labelled as the "February Revolution" or the "EDSA Revolution." On the other hand, all sorts of analyses have argued to the effect that the "EDSA Revolution" cannot be called a revolution, that it can best be described as a form of regime-change, a coup d'etat, a restoration, and so forth [see Carino 1986]. Yet to the hundreds of thousands of Filipinos from all social classes who massed on the streets that week there seemed to be no doubt that they were "making revolution" and that they were participating in "people power." For the revolution to be, it sufficed for them to throw caution aside (bahala na), to confront the tanks and guns of the state, to experience a couple of hours of solidarity with the anonymous crowd, and to participate in exorcising the forces of darkness (i. e., the Marcos regime). Should the business of naming the event a "revolution" be understood, then, simply in terms of its political referent? Whatever the reality of the processes enveloping them, the crowds on EDSA seemed to readily interpret or locate their experience within a familiar discourse of revolution and mass action. The present essay explores the discursive frame of radical politics from the 1950s up to 1986. I) I hope to explain why "revolution" and "people power" were familiar in 1986, as well as why the imagined "1986 EDSA revolution" also constitutes a departure or break from the Marcos/Communist Party discourse of revolution. -

Table of Contents.Pmd

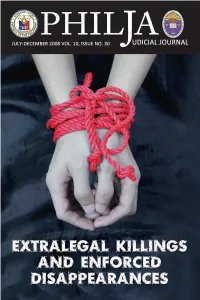

TheTheThe PHILPHILPHIL AAA JULY-DECEMBER 2008 VOL. 10, ISSUE NO. 30 JJJUDICIALUDICIALUDICIAL OURNALOURNALOURNAL EEEXTRALEGAL K KKILLINGSILLINGSILLINGS ANDANDAND E EENFORNFORNFORCEDCEDCED DDDISAPPEARANCES I.I. SI. SSPEECHESPEECHESPEECHES II.II. LII. LLECTURESECTURESECTURES III.III.III. TTTHEHEHE I IINTERNNTERNNTERNAAATIONTIONTIONALALAL B BBILLILLILL OFOFOF H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IVIVIV.. U. UUNIVERSAL H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IIINSTRNSTRNSTRUMENTSUMENTSUMENTS VVV.. I. IISSUSSUSSUANCESANCESANCES VI. RVI. REPOREPOREPORTSTSTS TTThe PHILJPHILJhe A JJA udicial JJudicial ourourournal.nal.nal. The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures. research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2008 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGO Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA MARTINEZ Hon. RENATO C. CORONA Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. -

Since Aquino: the Philippine Tangle and the United States

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 6 - 1986 (77) SINCE AQUINO: THE PHILIPPINE • TANGLE AND THE UNITED STATES ••' Justus M. van der Kroef SclloolofLAw UNivERsiTy of o• MARylANd. c:. ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Jaw-ling Joanne Chang Acting Managing Editor: Shaiw-chei Chuang Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, International Legal Studies Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion con tained therein. Subscription is US $15.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $20.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu.