THE PHILJA JUDICIAL JOURNAL Inspirational Messages from the Bench

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents.Pmd

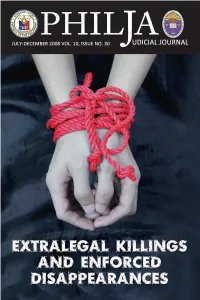

TheTheThe PHILPHILPHIL AAA JULY-DECEMBER 2008 VOL. 10, ISSUE NO. 30 JJJUDICIALUDICIALUDICIAL OURNALOURNALOURNAL EEEXTRALEGAL K KKILLINGSILLINGSILLINGS ANDANDAND E EENFORNFORNFORCEDCEDCED DDDISAPPEARANCES I.I. SI. SSPEECHESPEECHESPEECHES II.II. LII. LLECTURESECTURESECTURES III.III.III. TTTHEHEHE I IINTERNNTERNNTERNAAATIONTIONTIONALALAL B BBILLILLILL OFOFOF H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IVIVIV.. U. UUNIVERSAL H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IIINSTRNSTRNSTRUMENTSUMENTSUMENTS VVV.. I. IISSUSSUSSUANCESANCESANCES VI. RVI. REPOREPOREPORTSTSTS TTThe PHILJPHILJhe A JJA udicial JJudicial ourourournal.nal.nal. The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures. research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2008 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGO Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA MARTINEZ Hon. RENATO C. CORONA Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. -

The Scope, Justifications and Limitations of Extradecisional Judicial Activism and Governance in the Philippines*

THE SCOPE, JUSTIFICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS OF EXTRADECISIONAL JUDICIAL ACTIVISM AND GOVERNANCE IN THE PHILIPPINES* Bryan Dennis G. Tiojanco∗∗ ∗∗∗ Leandro Angelo Y. Aguirre “Political philosophy must analyze political history; it must distinguish what is due to the excellence of the people, and what to the excellence of the laws; it must carefully calculate the exact effect of each part of the constitution, though thus it may destroy many an idol of the multitude, and detect the secret utility where but few imagined it to lie.” – Bagehot1 I. INTRODUCTION Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in one of the most famous maxims in law, said that: The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed.2 * Awardee, Irene Cortes Prize for Best Paper in Constitutional Law (2009); Cite as Bryan Dennis Tiojanco & Leandro Angelo Aguirre, The Scope, Justifications and Limitations of Extradecisional Judicial Activism and Governance in the Philippines, 84 PHIL. L.J. 73, (page cited) (2009). ∗∗ Member, PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL (2005, 2007). J.D. University of the Philippines College of Law (2009). ∗∗∗ Chair, PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL (2006). Violeta Calvo-Drilon-ACCRALAW Scholar for Legal Writing (2006). J.D. University of the Philippines Collge of Law (2009). B.S. Communications Technology Management, Ateneo de Manila University (2004). 1 cited in WOODROW WILSON, CONGRESSIONAL GOVERNMENT: A STUDY IN AMERICAN POLITICS 193 (Meridian ed. -

A Universalist History of the 1987 Philippine Constitution (I)1

A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY OF THE 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION (I)1 2 Diane A. Desierto "To be non-Orientalist means to accept the continuing tension between the need to universalize our perceptions, analyses, and statements of values and the need to defend their particularist roots against the incursion of the particularist perceptions, analyses, and statements of values coming from others who claim they are putting forward universals. We are required to universalize our particulars and particularize our universals simultaneously and in a kind of constant dialectical exchange, which allows us to find new syntheses that are then of course instantly called into question. It is not an easy game." - Immanuel Wallerstein in EUROPEAN UNIVERSALISM: The Rhetoric of Power 3 "Sec.2. The Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation, and amity with all nations. Sec. 11. The State values the dignity of every human person and guarantees full respect for human rights." 4 - art. II, secs. 2 and 11, 1987 Philippine Constitution TABLE OF CONTENTS: I. INTRODUCTION.- II. REFLECTIONS OF UNIVERSALISM: IDEOLOGICAL CURRENTS AND THE HISTORICAL GENESIS OF UNIVERSALIST CONCEPTIONS IN THE 1987 CONSTITUTION.- 2.1. A Universalist Exegesis, and its Ideological Distinctions from Particularism and Cultural Relativism.- 2. 1.1. The Evolution of Universalism.- 2.2. Universalism vis-a- vis Particularism.- 2.3. Universalism's Persuasive Appeal in a Postmodern Era.- Ill. IDEOLOGICAL CURRENTS OF UNIVERSALISM IN THE HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION.- 3.1. -

(UPOU). an Explorat

his paper is a self-reflection on the state of openness of the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU). An exploratory and descriptive study, it aims not only to define the elements of openness of UPOU, but also to unravel the causes and solutions to the issues and concerns that limit its options to becoming a truly open university. It is based on four parameters of openness, which are widely universal in the literature, e.g., open admissions, open curricula, distance education at scale, and the co-creation, sharing and use of open educational resources (OER). It draws from the perception survey among peers, which the author conducted in UPOU in July and August 2012. It also relies on relevant secondary materials on the subject. What if you could revisit and download the questions you took during the UPCAT (University of the Philippines College Admission Test)? I received information that this will soon be a possibility. It’s not yet official though. For some people, including yours truly, this is the same set of questions that made and unmade dreams. Not all UPCAT takers make it. Only a small fraction pass the test. Some of the passers see it as a blessing. Some see it as fuel, firing their desire to keep working harder. Some see it as an entitlement — instant membership to an elite group. Whatever its worth, the UPCAT is the entryway to the University of the Philippines, a scholastic community with a unique and celebrated tradition spanning more than a century. But take heed — none of its legacy would have been possible if not for the hard work of Filipino taxpayers. -

Leveraging Presidential Power: Separation of Powers Without Checks and Balances in Argentina and the Philippines Susan Rose-Ackerman, Diane A

Leveraging Presidential Power: Separation of Powers without Checks and Balances in Argentina and the Philippines Susan Rose-Ackerman, Diane A. Desierto, and Natalia Volosin1 Abstract: Independently elected presidents invoke the separation of powers as a justification to act unilaterally without checks from the legislature, the courts, or other oversight bodies. Using the cases of Argentina and the Philippines, we demonstrate the negative consequences for democracy arising from presidential assertions of unilateral power. In both countries the constitutional texts have proved inadequate to check presidents determined to interpret or ignore the text in their own interests. We review five linked issues: the president’s position in the formal constitutional structure, the use of decrees and other law-like instruments, the management of the budget, appointments, and the role of oversight bodies, including the courts. We stress how emergency powers, arising from poor economic conditions in Argentina and from civil strife in the Philippines, have enhanced presidential power. Presidents seek to enhance their power by taking unilateral actions, especially in times of crisis, and then assert that the constitutional separation of powers is a shield that protects them from scrutiny and that undermines others’ claims to exercise checks and balances. Presidential power is difficult to control through formal institutional checks. Constitutional and statutory limits have some effect, but they also generate the search for ways to work around them. Both our cases illustrate the dangers of raising the separation of powers to a canonical principle without a robust system of checks and balances to counter assertions of executive power. Argentina and the Philippines may be extreme cases, but the fact that their recent constitutional revisions were explicitly designed to curb the president, should give us pause. -

Redalyc.A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY of the 1987 PHILIPPINE

Historia Constitucional E-ISSN: 1576-4729 [email protected] Universidad de Oviedo España Desierto, Diane A. A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY OF THE 1987 PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION (I) Historia Constitucional, núm. 10, septiembre, 2009, pp. 383-444 Universidad de Oviedo Oviedo, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=259027582013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative A UNIVERSALIST HISTORY OF THE 1987 PHILIPPINE 1 CONSTITUTION (I) Diane A. Desierto2 “To be non-Orientalist means to accept the continuing tension between the need to universalize our perceptions, analyses, and statements of values and the need to defend their particularist roots against the incursion of the particularist perceptions, analyses, and statements of values coming from others who claim they are putting forward universals. We are required to universalize our particulars and particularize our universals simultaneously and in a kind of constant dialectical exchange, which allows us to find new syntheses that are then of course instantly called into question. It is not an easy game.” - Immanuel Wallerstein in EUROPEAN UNIVERSALISM: The Rhetoric of Power3 “Sec.2. The Philippines renounces war as an instrument of national policy, adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation, and amity with all nations. Sec. 11. The State values the dignity of every human person and guarantees full respect for human rights.” - art. -

Philippine Bar Examination

Philippine Bar Examination . 12.1.1 Presidents and Vice- Presidents From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia . 12.1.2 Supreme Court and Court of Appeals Justices The Philippine Bar Examination is the professional . 12.1.3 Senators and Representatives licensure examination for lawyers in the Philippines. 12.1.4 Appointees and career service officials 12.1.5 Local officials It is the only professional licensure exam in the . 12.1.6 Academe country that is not supervised by the Professional . 12.1.7 Private sector Regulation Commission. The exam is exclusively . administered by the Supreme Court of the Philippines 13 1st place in the Philippine Bar Examinations through the Supreme Court Bar Examination Committee. 14 External links 15 See also Contents 16 References 1 Brief history Brief history 2 Admission requirements The first Philippine Bar Exams was given in 1903 but 3 Committee of Bar Examiners the results were released in 1905. Jose I. Quintos 4 Bar review programs obtained the highest rating of 96.33%, Sergio Osmena, 5 Venue and itinerary Sr. was second with 95.66%, F. Salas was third with 6 Coverage 94.5% and Manuel L.Quezon fourth with 87.83%. The 7 Grading system first bar exam was held in 1903, with 13 examinees, o 7.1 Passing average vs. Passing rate while the 2008 bar examination is the 107th (given o 7.2 Passing Percentage (1978-2012) per Article 8, Section 5, 1987 Constitution). The o 7.3 Law school passing rates 2001 bar exam had the highest number of passers—1,266 o 7.4 Role of the Supreme Court, Criticisms out of 3,849 examinees, or 32.89%, while 2006 had the o 7.5 Bar topnotchers highest examinees -.6,187. -

Case1.Credit

RELATED TITLES Documents Politics & Current Affairs Politics 0 0 6 views Case1.Credit Uploaded by Claire Roxas Mixed Interest National Bank OID Demystified Magna Carta 2nd credit trans Full description Financing Act a/k/a (Somewhat) Dra�-08 June Save Embed Share Print Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Baguio City FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. 114286 April 19, 2001 THE CONSOLIDATED BANK AND TRUST CORPORATION (SOLIDBANK), petitioner vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS, CONTINENTAL CEMENT CORPORATION, GREGORY T. LIM and SPOUSE,respondents. YNARES-SANTIAGO, J .: The instant petition for review seeks to partially set aside the July 26, 1993 Decision1 of respondent Court of Appeals in CA-GR. CV No. 29950, insofar as it orders petitioner to reimburse respondent Continental Cement Corporation the amount of P490, 228.90 with interest thereon at the legal rate from July 26, 1988 until fully paid. The petition also seeks to set aside the March 8, 1994 Resolution2 of respondent Court of Appeals denying its Motion for Reconsideration. The facts are as follows: On July 13, 1982, respondents Continental Cement Corporation (hereinafter, respondent Corporation) and Gregory T. Lim (hereinafter, respondent Lim) obtained from petitioner Consolidated Bank and Trust Corporation Letter of Credit No. DOM-23277 in the amount of P 1,068,150.00 On the same date, respondent Corporation paid a marginal deposit of P320,445.00 to petitioner. The letter of credit was used to purchase around five hundred thousand liters of bunker fuel oil from Petrophil Corporation, which the latter delivered directly to respondent Corporation in its Bulacan plant. In relation to the same transaction, a trust receipt for the amount of P 1,001,520.93 was executed by respondent Corporation, with respondent Lim as signatory. -

Oscar Franklin B. Tan**

ARTICULATING THE COMPLETE PHILIPPINE RIGHT TO PRIVACY IN CONSTITUTIONAL AND CIVIL LAW: A TRIBUTE TO CHIEF JUSTICE FERNANDO AND JUSTICE CARPIO* Oscar Franklin B. Tan** “The stand for privacy, however, need not be taken as hostility against other individuals, against government, or against society. It is but an assertion by the individual of his inviolate personality.” —Dean and Justice Irene Cortes1 * This author acknowledges his professors: Justice Vicente V. Mendoza, Dean Bartolome Carale, Dean Merlin Magallona, Araceli Baviera, Domingo Disini, Carmelo Sison, Myrna Feliciano, Eduardo Labitag, Emmanuel Fernando, Antonio Bautista, Elizabeth Aquiling- Pangalangan, Danilo Concepcion, Rogelio Vinluan, Teresita Herbosa, Rafael Morales, Vicente Amador, Sylvette Tankiang, Susan Villanueva, Francis Sobrevinas, Anacleto “Butch” Diaz, Rudyard Avila, H. Harry Roque, Concepcion Jardeleza, Antonio Santos, Patricia Daway, Gwen Grecia-De Vera, JJ Disini, Barry Gutierrez, Florin Hilbay, Magnolia Mabel Movido, Solomon Lumba, and Ed Robles, as well as his Harvard Law School professors Laurence Tribe, Frank Michelman, and Justice Richard Goldstone of the South African Constitutional Court. This author most especially Deans Pacifico Agabin and Raul Pangalangan who first encouraged him to take up legal writing during his freshman year. This author also thanks the following who reviewed and assisted in finalizing this article: Gerard Joseph Jumamil, Bo Tiojanco, Leandro Aguirre, John Fajardo, Joseph Valmonte, Miguel Francisco Cruz, Mark Garrido, and Romualdo Menzon Jr. All errors remain the author’s alone. ** Chair, PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL (2005). Associate (International Capital Markets), Allen & Overy LLP London. LL.M., Harvard Law School (Commencement Speaker) (2007). LL.B., University of the Philippines (2005). B.S. Management Engineering / A.B. -

Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century

Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century Well over a decade has passed since the dramatic ‘People Power Revolution’ in Manila, yet until now no book-length study has emerged to examine the manifold changes underway in the Philippines in the post-Marcos era. This book fills that gap. Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century offers historical depth and sophisticated theoretical insight into contemporary life in the archipelago. Organised as a set of interrelated thematic essays rather than a chronological account, the book addresses key topics which will be of interest to the academic and non-academic reader, such as trends in national-level and local politics, the role of ethnic-Chinese capital in the Philippine economy, nationalism and popular culture, and various forms of political violence and extra-electoral contestation. Drawing on a wide variety of primary and secondary sources, as well as over a decade of research and work in the area, Hedman and Sidel provide an invaluable overview of the contemporary and historical scene of a much misunderstood part of Southeast Asia. This book fills an important gap in the literature for readers interested in understanding the Philippines as well as students of Asian studies, comparative politics, political economy and cultural studies. Eva-Lotta E. Hedman is Lecturer in Asian-Pacific Politics at the University of Nottingham. John T. Sidel is Lecturer in Southeast Asian Politics at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Politics in Asia series Edited by Michael Leifer London School of Economics ASEAN and the Security of South-East Korea versus Korea Asia A case of contested legitimacy Michael Leifer B.K. -

ERNESTO B. FRANCISCO, JR., Petitioner, NAGMAMALASAKIT NA

ERNESTO B. FRANCISCO, JR., petitioner, NAGMAMALASAKIT NA MGA MANANANGGOL NG MGA MANGGAGAWANG PILIPINO, INC., ITS OFFICERS AND MEMBERS, petitioner-in-intervention, WORLD WAR II VETERANS LEGIONARIES OF THE PHILIPPINES, INC., petitioner-in-intervention vs. THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, REPRESENTED BY SPEAKER JOSE G. DE VENECIA, THE SENATE, REPRESENTED BY SENATE PRESIDENT FRANKLIN M. DRILON, REPRESENTATIVE GILBERTO C. TEODORO, JR. AND REPRESENTATIVE FELIX WILLIAM B. FUENTEBELLA, respondents, JAIME N. SORIANO, respondent-in-Intervention, SENATOR AQUILINO Q. PIMENTEL, respondent-in-intervention. 2003-11-10 | G.R. No. 160261 EN BANC D E C I S I O N CARPIO MORALES, J.: There can be no constitutional crisis arising from a conflict, no matter how passionate and seemingly irreconcilable it may appear to be, over the determination by the independent branches of government of the nature, scope and extent of their respective constitutional powers where the Constitution itself provides for the means and bases for its resolution. Our nation's history is replete with vivid illustrations of the often frictional, at times turbulent, dynamics of the relationship among these co-equal branches. This Court is confronted with one such today involving the legislature and the judiciary which has drawn legal luminaries to chart antipodal courses and not a few of our countrymen to vent cacophonous sentiments thereon. There may indeed be some legitimacy to the characterization that the present controversy subject of the instant petitions - whether the filing of the second impeachment complaint against Chief Justice Hilario G. Davide, Jr. with the House of Representatives falls within the one year bar provided in the Constitution, and whether the resolution thereof is a political question - has resulted in a political crisis. -

The State of Philippine Legal Education Revisited

The State of Philippine Legal Education Revisited MARIANO F. MAGSALIN, JR.∗ Introduction Imagine a “virtual” panel of the most erudite and specialized law mentors imparting their field of expertise, assisted and complemented by state-of-the-art teaching tools, in downloadable real time for the consumption of students in the comfort and convenience of their homes, workstations or wherever their personal digital assistants take them. Feedback or recitation, examinations and grade dissemination are all done through e-mail or its faster and higher-resolution counterpart. Verily, the paper chase is still on but pursued in a different matrix. This is, or should be, according to some Western legal educators, legal education in the digital age. A counterpoint to this idyllic scenario is Philippine legal education, the development of which may be characterized at best, as spinning on its wheels. For decades, the future of law students has been obdurately consigned to an impractical, inefficient, wagering system, totally subservient to an antiquated bar examination requirement. Many Philippine lawyers have labeled themselves as the best in Asia because of what they perceive to be a difficult rite of passage that is the bar examination, and yet, Philippine law schools have not figured at all as a factor in surveys of the best universities in Asia. Reforms in Philippine legal education have moved glacially. While many foreign law schools have already responded and adapted to the demands of an increasingly globalized and borderless world, the concerns of many law schools in the Philippines are still centered on survival and viability. Competition is at best described as cutthroat and unfair.