Oscar Franklin B. Tan**

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![J. Leonen, En Banc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0526/j-leonen-en-banc-300526.webp)

J. Leonen, En Banc]

EN BANC G.R. No. 221697 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and ESTRELLA C. ELAMPARO, Respondents. G.R. No. 221698-700 - MARY GRACE NATIVIDAD S. POE LLAMANZARES, Petitioner, vs. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, FRANCISCO S. TATAD, ANTONIO P. CONTRERAS, and AMADO T. VALDEZ, Respondents. Promulgated: March 8, 2016 x---------------------------------------------------------------------~~o=;::.-~ CONCURRING OPINION LEONEN, J.: I am honored to concur with the ponencia of my esteemed colleague, Associate Justice Jose Portugal Perez. I submit this Opinion to further clarify my position. Prefatory The rule of law we swore to uphold is nothing but the rule ofjust law. The rule of law does not require insistence in elaborate, strained, irrational, and irrelevant technical interpretation when there can be a clear and rational interpretation that is more just and humane while equally bound by the limits of legal text. The Constitution, as fundamental law, defines the mm1mum qualifications for a person to present his or her candidacy to run for President. It is this same fundamental law which prescribes that it is the People, in their sovereign capacity as electorate, to determine who among the candidates is best qualified for that position. In the guise of judicial review, this court is not empowered to constrict the electorate's choice by sustaining the Commission on Elections' actions that show that it failed to disregard doctrinal interpretation of its powers under Section 78 of the Omnibus Election Code, created novel jurisprudence in relation to the citizenship of foundlings, misinterpreted and misapplied existing jurisprudence relating to the requirement of residency for election purposes, and declined to appreciate the evidence presented by petitioner as a whole and instead insisted only on three factual grounds j Concurring Opinion 2 G.R. -

The Celebrity's Right to Autonomous Self-Definition

65 THE CELEBRITY’S RIGHT TO AUTONOMOUS SELF-DEFINITION AND FALSE ENDORSEMENTS: ARGUING THE CASE FOR A RIGHT OF PUBLICITY IN THE PHILIPPINES Arvin Kristopher A Razon* Abstract With the Philippines being the top country in terms of social media usage, social media platforms have expanded opportunities for celebrities to profit from their fame. Despite the pervasiveness of celebrity culture in the country and the increasing number of unauthorised celebrity advertisements in such platforms, the right of publicity does not explicitly exist in Philippine law. This paper explains that the lack of an explicit statute-based right of publicity does not mean that it does not exist in common law or other statutory law. Centred on the minimalist path of law reform, the paper argues that the existing right to privacy in Philippine law can justify a right to publicity, anchored on the right to protect unwarranted publicity about oneself regardless of one’s status in the public eye, as well as on the right to autonomous self-definition. The illustrative cases in this paper evidence the hurt feelings celebrities suffer from unwanted publicity. A publicity right also exists as a property right under local intellectual property laws on unfair competition. I. Introduction The opportunity to economically exploit one’s name, likeness or identity, often through celebrity endorsements, is a perk that comes with being a celebrity.1 The internet, particularly social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, has expanded the opportunities for celebrities to profit from their fame, providing them with another channel by which they can endorse brands to a global audience, * BA Organizational Communication (magna cum laude), Juris Doctor (University of the Philippines), LLM (University of Melbourne); Lecturer, De La Salle University. -

Couegeof Law, Univerbity of the Philippines the President Univ

THE DEAN'S REPORT, 1963·64 CoUege of Law, UniverBity of the Philippines The President Univ,ersityof the Philippines Diliman, QuezonCity Sir: I have to submit the following report on the operation and ac- tivities of the Collegeof Law for the academic year 1963-1964. I ,THE U.P. LAW CENTER: OPPORTUNITY AND CHALLENGE Speaking in 1925 at the dedication ceremonies of the Lawyers Club of the University of Michigan Law School-the law school which gave us our beloved founder and first dean, the late Justice George A. Malcolm-J ames Parker Hall, then Dean of the Univer- sity of Chicago Law Schoolstated:1 "A change is taking place in the conception of the proper function of a University law school. Until very late7iy it was conceived aMno8t whoUy laB a high-grade prOfessional, traimimg school, employingit was true, scholarly methods and exacting standards of study and achievement, but only indirectly seeking to improve the substance and administration of our law. The law, it was assured, was what the courts and legislatures made it, and the task of the law school was to analyze, comprehend,and classify this product, and to pass on to students a similar power of ana- lysis, comprehension,and classification, as regards at least the principal topics of the law, so as to enable them worthily and successfully to play their parts as judges and lawyers in the lists of future litigation." Dean Hall, how.ever,was quick to reassure his listeners-which undoubtedly included a group of law teachers-that this primary law schoolfunction of providing "high grade professional training," was unquestionably a worthy one; that, indeed, it should be prior to all others. -

Duterte Seeks Martial Law Extension to Fight Communist Rebels

STEALING FREE NEWSPAPER IS STILL A CRIME ! AB 2612, PLESCIA CRIME PH credit rating up WEEKLY ISSUE 70 CITIES IN 11 STATES ONLINE Vol. IX Issue 453 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 December 14 - 20, 2017 Body cams, ‘not God,’ to hold dirty Duterte seeks martial law extension cops accountable By Macon Araneta FilAm Star Correspondent PH NEWS | A3 to fight communist rebels Sen. Win Gatchalian said it is Full SSS benefits for By Daniel Llanto | FilAm Star Correspondent “absolutely absurd” to suggest that the fear of divine retribution in the after- Pinoys in Germany, Sweden An extension of martial law in life would be more effective than body Mindanao for one more year no longer cameras in holding dirty cops account- stands to reason since the military has able for their crimes here on Earth. long demolished the Islamic State- Gatchalian, an ally of President linked Maute terrorists. But President Rodrigo Duterte, was reacting strongly Duterte cited communist rebels as to the statement of Philippine National justification for another year-long Police (PNP) Drug Enforcement Group extension. (DEG) Director Chief Superintendent The threat posed by the New Joseph Adnol, who was quoted by re- People’s Army (NPA) was the chief rea- porters as saying: “For me, there really PH NEWS | A3 son cited by Duterte in his request for is no need for a body cam, our camera Congress to extend martial law in Min- as policemen is God, ‘yun ang pinaka- Why PH has slowest, danao by one more year. -

THE PHILJA JUDICIAL JOURNAL Inspirational Messages from the Bench

THE PHILJA JUDICIAL JOURNAL Inspirational Messages From The Bench January - December 1999 OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2000 Vol. 2, Issue No. 6 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. HILARIO G. DAVIDE, Jr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. JOSUE N. BELLOSILLO Hon. JOSE A.R. MELO Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO Hon. JOSE C. VITUG Hon. SANTIAGO M. KAPUNAN Hon. VICENTE V. MENDOZA Hon. ARTEMIO V. PANGANIBAN Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. FIDEL P. PURISIMA Hon. BERNARDO P. PARDO Hon. ARTURO B. BUENA Hon. MINERVA GONZAGA REYES Hon. CONSUELO YÑARES-SANTIAGO Hon. SABINO R. DE LEON COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. ALFREDO L. BENIPAYO DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. REYNALDO L. SUAREZ Hon. ZENAIDA N. ELEPAÑO Hon. BERNARDO T. PONFERRADA CLERK OF COURT Attorney LUZVIMINDA D. PUNO ASST. COURT ADMINISTRATORS Attorney ANTONIO H. DUJUA Attorney JOSE P. PEREZ Attorney ISMAEL G. KHAN, Jr. (Chief, Public Information Office) ASST. CLERK OF COURT Attorney MA. LUISA D. VILLARAMA DIVISION CLERKS OF COURT Attorney VIRGINIA A. SORIANO Attorney TOMASITA M. DRIS Attorney JULIETA Y. CARREON PHILIPPINE JUDICIAL ACADEMY Board of Trustees Hon. HILARIO G. DAVIDE Jr. Chief Justice Chairman Hon. JOSUE N. BELLOSILLO Senior Associate Justice, Supreme Court Vice-Chairman Members Hon. AMEURFINA A. MELENCIO HERRERA Hon. ALFREDO L. BENIPAYO Chancellor Court Administrator Hon. SALOME A. MONTOYA Hon. FRANCIS E. GARCHITORENA Presiding Justice, Court of Appeals Presiding Justice, Sandiganbayan Hon. DANILO B. PINE Dean HERNANDO B. PEREZ President, Philippine Judges Association President, Philippine Association of Law Schools Executive Officials Hon. AMEURFINA A. MELENCIO HERRERA Chancellor Hon. ANTONIO M. MARTINEZ Vice-Chancellor Hon. PRISCILA S. AGANA Executive Secretary Attorney EDWIN R. -

1 PROF. DR. DIANE A. DESIERTO (JSD, Yale) Associate Professor Of

PROF. DR. DIANE A. DESIERTO (JSD, Yale) Associate Professor of Law (tenured) Michael J. Marks Distinguished Professor in Business Law, Co-Director, ASEAN Law & Integration Center (ALIC), William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Rm. 257, 2515 Dole Street, Honolulu, HI 96822-2350 Phone: (808) 956 0417 Fax: (808) 956 8313 Mobile: +1 (808) 285 5779 Website: https://www.law.hawaii.edu/person/diane-desierto Fellow, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (CASBS), Stanford University, 75 Alta Road, Stanford CA 94305 https://casbs.stanford.edu/diane-desierto, and Research Fellow, WSD Handa Center for Human Rights and International Justice, Stanford Global Studies Division, Stanford University, https://handacenter.stanford.edu/people/diane-desierto-research- fellow 2017 Director of Studies for Public International Law and Visiting Professor, Hague Academy of International Law Specializations: International Law and International Dispute Settlement, International Investment and Commercial Arbitration Law, International Economic Law (World Trade, International Finance, International Investment, Law & Development), International Maritime Security, ASEAN Law, IHL & IHR in ASEAN, Comparative Constitutional Law, Business Associations GLOBAL PROFESSIONAL and ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Member of the Scientific Advisory Board, European Journal of International Law Permanent Editor, EJIL:Talk! (official blog of the European Journal of IL) Academic Council Member, Institute of Transnational Arbitration (ITA) Co-Chair, Oxford -

Motion for Reconsideration

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUPREME COURT MANILA EN BANC REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, REPRESENTED BY SOLICITOR GENERAL JOSE C. CALIDA, Petitioner, – versus – CHIEF JUSTICE MARIA LOURDES P.A. G.R. No. SERENO, 237428 For: Quo Warranto Respondent. Senators LEILA M. DE LIMA and ANTONIO “SONNY” F. TRILLANES IV, Movant-Intervenors. x-------------------------------------------------------------------x MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION Movant-intervenors, Senators LEILA M. DE LIMA and ANTONIO “SONNY” F. TRILLANES IV, through undersigned counsel, respectfully state that: 1. On 29 May 2018, Movant-intervenors, in such capacity, requested and obtained a copy of the Decision of the Supreme Court dated 11 May 2018, by which eight members of the Court voted to grant the Petition for Quo Warranto, resulting in the ouster of Chief Justice Maria Lourdes P.A. Sereno. 2. The Supreme Court’s majority decision, penned by Justice Tijam, ruled that: 2.1. There are no grounds to grant the motion for inhibition filed by respondent Chief Justice Sereno; 2.2. Impeachment is not an exclusive means for the removal of an impeachable public official; MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION Republic of the Philippines v. Sereno G.R. No. 237428 Page 2 of 25 2.3. The instant Petition for Quo Warranto could proceed independently and simultaneously with an impeachment; 2.4. The Supreme Court’s taking cognizance of the Petition for Quo Warranto is not violative of the doctrine of separation of powers; 2.5. The Petition is not dismissable on the Ground of Prescription, as “[p]rescription does not lie against the State”; and 2.6. The Petitioner sufficiently proved that Respondent violated the SALN Law, and such failure amounts to proof of lack of integrity of the Respondent to be considered, much less nominated appointed, as Chief Justice by the Judicial and Bar Council and the President of Republic, respectively. -

Table of Contents.Pmd

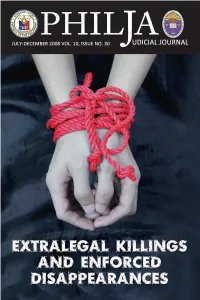

TheTheThe PHILPHILPHIL AAA JULY-DECEMBER 2008 VOL. 10, ISSUE NO. 30 JJJUDICIALUDICIALUDICIAL OURNALOURNALOURNAL EEEXTRALEGAL K KKILLINGSILLINGSILLINGS ANDANDAND E EENFORNFORNFORCEDCEDCED DDDISAPPEARANCES I.I. SI. SSPEECHESPEECHESPEECHES II.II. LII. LLECTURESECTURESECTURES III.III.III. TTTHEHEHE I IINTERNNTERNNTERNAAATIONTIONTIONALALAL B BBILLILLILL OFOFOF H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IVIVIV.. U. UUNIVERSAL H HHUMANUMANUMAN R RRIGHTSIGHTSIGHTS IIINSTRNSTRNSTRUMENTSUMENTSUMENTS VVV.. I. IISSUSSUSSUANCESANCESANCES VI. RVI. REPOREPOREPORTSTSTS TTThe PHILJPHILJhe A JJA udicial JJudicial ourourournal.nal.nal. The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures. research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2008 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. LEONARDO A. QUISUMBING Hon. CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGO Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA MARTINEZ Hon. RENATO C. CORONA Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. -

Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno Distinguished Lectures Series of 2010

The PHILJA Judicial Journal The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures, research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit the materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2010 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. RENATO C. CORONA ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, Jr. Hon. ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA Hon. TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE CASTRO Hon. ARTURO D. BRION Hon. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Hon. LUCAS P. BERSAMIN Hon. MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO Hon. ROBERTO A. ABAD Hon. MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, Jr. Hon. JOSE P. PEREZ Hon. JOSE C. MENDOZA COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. JOSE MIDAS P. MARQUEZ DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. NIMFA C. VILCHES Hon. EDWIN A. VILLASOR Hon. RAUL B. VILLANUEVA CLERK OF COURT Atty. MA. -

The Scope, Justifications and Limitations of Extradecisional Judicial Activism and Governance in the Philippines*

THE SCOPE, JUSTIFICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS OF EXTRADECISIONAL JUDICIAL ACTIVISM AND GOVERNANCE IN THE PHILIPPINES* Bryan Dennis G. Tiojanco∗∗ ∗∗∗ Leandro Angelo Y. Aguirre “Political philosophy must analyze political history; it must distinguish what is due to the excellence of the people, and what to the excellence of the laws; it must carefully calculate the exact effect of each part of the constitution, though thus it may destroy many an idol of the multitude, and detect the secret utility where but few imagined it to lie.” – Bagehot1 I. INTRODUCTION Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in one of the most famous maxims in law, said that: The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed.2 * Awardee, Irene Cortes Prize for Best Paper in Constitutional Law (2009); Cite as Bryan Dennis Tiojanco & Leandro Angelo Aguirre, The Scope, Justifications and Limitations of Extradecisional Judicial Activism and Governance in the Philippines, 84 PHIL. L.J. 73, (page cited) (2009). ∗∗ Member, PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL (2005, 2007). J.D. University of the Philippines College of Law (2009). ∗∗∗ Chair, PHILIPPINE LAW JOURNAL (2006). Violeta Calvo-Drilon-ACCRALAW Scholar for Legal Writing (2006). J.D. University of the Philippines Collge of Law (2009). B.S. Communications Technology Management, Ateneo de Manila University (2004). 1 cited in WOODROW WILSON, CONGRESSIONAL GOVERNMENT: A STUDY IN AMERICAN POLITICS 193 (Meridian ed. -

PROF. DR. DIANE A. DESIERTO Assistant Professor of Law and Co-Director, ASEAN Law & Integration Center (ALIC), University of Hawaii William S

PROF. DR. DIANE A. DESIERTO Assistant Professor of Law and Co-Director, ASEAN Law & Integration Center (ALIC), University of Hawaii William S. Richardson School of Law, Rm. 210, 2515 Dole Street Honolulu Hawaii 96822-2350 USA Adjunct Fellow East-West Center Rm. 3078, East-West Center, Burns Hall, 1601 East-West Center Road, Honolulu, Hawaii USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] https://www.law.hawaii.edu/person/diane-desierto http://www.eastwestcenter.org/about-ewc/directory/diane.desierto +1 808 285 5779 (US mobile), +1 808 956 0417 (office landline), +63 917 8012113 (intl mobile) EDUCATION Yale Law School September 2009-June 2011 JSD (Doctor of the Science of Law) (advance of 2014 deadline) Dissertation: “Necessity and National Emergency Clauses: A Study of Sovereignty in Modern Treaty Interpretation” (Supervisor: Prof. W. Michael Reisman, Dissertation Readers: Prof. Susan Rose-Ackerman, Prof. Roberta Brilmayer) Awarded Yale Law School’s 2010-2011 Ambrose Gherini Prize in International Law for most outstanding work in international law, public or private Honors and positions: Howard M. Holtzmann Fellowship in International Arbitration and Dispute Resolution; Lillian Goldman Perpetual Scholarship; 2010- 2011 YLS Public Interest Fellowship for clerkship at the International Court of Justice, Peace Palace, the Hague, Netherlands (Chambers of H.E. Judge Bruno Simma and H.E. Judge Bernardo Sepulveda-Amor); Editor, Yale Journal of International Law; Coordinator, Yale Forum on International Law Yale Law School September 2008-June 2009 LLM (Master of Laws) Conferred “Honours” marks in all international law and comparative law courses Honors and positions: Lillian Goldman Scholarship; Executive Board Member, Yale Multidisciplinary Research Forum; Coordinator, Yale Forum on International Law University of the Philippines June 2000-April 2004 LLB (Bachelor of Laws/degree renamed to Juris Doctor) Cum Laude, Class Salutatorian, Phi Kappa Phi International Honor Society University Scholar and College Scholar 2004 Justice Irene P. -

Searching for Success

Searching for Success in Judicial Reform TECHNICAL EDITOR: Livingston Armytage NETWORK FACILITATOR: Lorenz Metzner Searching for Success in Judicial Reform Voices from the Asia Pacific Experience Asia Pacific Judicial Reform Forum 1 1 YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in India by Oxford University Press, New Delhi © United Nations Development Programme 2009 This publication was prepared in partnership with the Asia Pacific Judicial Reform Forum (APJRF) The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization.