Silencing the Opposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Federalist Era 1787-1800

THE FEDERALIST ERA 1787-1800 Articles of Confederation: the first form of government. *NATIONAL GOVERNMENT TOO WEAK! Too much state power “friendship of states” examples of being too weak: • No President/No executive • Congress can’t tax or raise an army • States are coining their own money • Foreign troubles (British on the frontier, French in New Orleans) Shays’ Rebellion: Daniel Shays is a farmer in Massachusetts protesting tax collectors. The rebellion is a wake up call - recognize we need a new government Constitutional Convention of 1787: Delegates meet to revise the Articles, instead draft a new Constitution • Major issue discussed = REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS (more representatives in Congress, more influence you have in passing laws/policies in your favor) NJ Plan (equal per state) vs. Virginia Plan (based on population) House of Representatives: GREAT COMPROMISE Based on population Creates a bicameral Senate: (two-house) legislature Equal, two per state THREE-FIFTHS • 3 out of every 5 slaves will count for representation and taxation COMPROMISE • increases representation in Congress for South Other Compromises: • Congress regulates interstate and foreign trade COMMERCIAL • Can tax imports (tariffs) but not exports COMPROMISE • Slave trade continued until 1808 How did the Constitution fix the problems of the Articles of Confederation? ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION CONSTITUTION • States have the most power, national • states have some power, national government government has little has most • No President or executive to carry out -

John Adams Contemporaries

17 150-163 Found2 AK 9/13/07 11:27 AM Page 150 Answer Key John Adams contemporaries. These students may point out that Adams penned defenses Handout A—John Adams of American rights in the 1770s and was (1735–1826) one of the earliest advocates of colonial 1. Adams played a leading role in the First independence from Great Britain. They Continental Congress, serving on ninety may also mention that his authorship committees and chairing twenty-five of of the Massachusetts Constitution and these.An early advocate of independence Declaration of Rights of 1780 makes from Great Britain, in 1776 he penned him a champion of individual liberty. his Thoughts on Government, describing 5. Some students may suggest that gov- how government should be arranged. ernment may limit speech when the He headed the committee charged public safety requires it. Others may with writing the Declaration of Inde- suggest that offensive or obscene pendence. He served on the commis- speech may be restricted. Still other sion that negotiated the Treaty of Paris, students will argue against any limita- which ended the Revolutionary War. tions on freedom of speech. 2. Adams was not present at the Consti- tutional Convention. However, while serving as an American diplomat in Handout B—Vocabulary and London, he followed the proceedings. Context Questions Adams and Jefferson urged Congress 1. Vocabulary to yield to the Anti-Federalist demand a. disagreed for the Bill of Rights as a condition for b. caused ratifying the proposed Constitution. c. until now 3. The Alien and Sedition Acts gave the d. -

Alien and Sedition Acts • Explain Significance of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions Do Now “The Vietnam War Was Lost in America

Adams SWBAT • Explain significance of the Alien and Sedition Acts • Explain significance of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions Do Now “The Vietnam War was lost in America. Public opinion killed any prospect of victory.” • What is the meaning of this statement? • What is more important, liberty (ie. free speech) or order (ie. security)? John Adams President John Adams • John Adams (Federalist) becomes President in 1797 *Due to an awkward feature of the Constitution, Jefferson becomes VP John Adams • During his presidency Adams passed the Alien and Sedition Acts • How does the cartoonist portray Adam’s actions? Alien and Sedition Acts, 1798 • Required immigrants to live in the Naturalization Act U.S. for l4 years before becoming a citizen • Allowed President to expel foreigners from the U.S. if he Alien Act believes they are dangerous to the nation's peace & safety • Allowed President to imprison or Alien Enemies Act expel foreigners considered dangerous in time of war • Barred American citizens from saying, writing, or publishing any Sedition Act false, scandalous, or malicious statements about the U.S. Gov, Congress, or the President Alien and Sedition Acts • The 4 acts together became known as the Alien and Sedition Acts • Response to the Alien and Sedition Acts: - Kentucky & Virginia Resolutions - (written by T. Jefferson & J. Madison) declared the Acts unconstitutional Virginia & Kentucky Resolutions 1. Called for the states to declare the Alien and Sedition Act null & void (invalid) 2. Introduced concept of nullification (ignoring -

Alien and Sedition Acts

• On your own, SILENTLY look at the three pictures and notate them as follows: • ! “reminds me of…” • ? “a question I have …” • * “an Ah-ha moment, or something interesting about the image is…” • With your partner, discuss your annotations. • Then, together write a summary statement of how this cartoon relates to the Alien and Sedition Acts. http://b1969d.medialib.glogster.com/media/8f36eeb83766a5f6047b82cfdb0e2b0c377d000ec198aab5deecb96deec3e660/sedition.jpg John Adams wins the election of 1796. • Thomas Jefferson becomes the Vice President. • The United States now has a Federalist President and a Republican Vice President. • The U.S. was in the middle of a dispute with France when Adams takes office. • President Adams would send diplomats to Paris to try to resolve the dispute. France was attacking U.S. shipping in route to England. Charles Pinkney, John Marshall, and Eldridge Gerry were U.S. Diplomats to France. 3 French envoys known as (X,Y, and Z) demanded a bribe of $250,000 to enter negotiations. The U.S. refused. The French government was corrupt and attacking U.S. merchants. The U.S. wanted war. 1797 - The XYZ Affair • In 1798 the United States stood on the brink of war with Alien and France. The Federalists believed that Democratic- Sedition Republican criticism of Federalist policies was disloyal Acts (1798) and feared that aliens (immigrants from France) living in the United States would sympathize with the French during a war. As a result, a Federalist-controlled Congress passed four laws, known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws raised the residency requirements for citizenship from 5 to 14 years, authorized the President to deport aliens, and permitted their arrest, imprisonment, and deportation during wartime. -

Like It Or Not, Trump Has a Point: FISA Reform and the Appearance of Partisanship in Intelligence Investigations by Stewart Baker1

Like It or Not, Trump Has a Point: FISA Reform and the Appearance of Partisanship in Intelligence Investigations by Stewart Baker1 To protect the country from existential threats, its intelligence capabilities need to be extraordinary -- and extraordinarily intrusive. The more intrusive they are, the greater the risk they will be abused. So, since the attacks of 9/11, debate over civil liberties has focused almost exclusively on the threat that intelligence abuses pose to the individuals and disfavored minorities. That made sense when our intelligence agencies were focused on terrorism carried out by small groups of individuals. But a look around the world shows that intelligence agencies can be abused in ways that are even more dangerous, not just to individuals but to democracy. Using security agencies to surveil and suppress political opponents is always a temptation for those in power. It is a temptation from which the United States has not escaped. The FBI’s director for life, J. Edgar Hoover, famously maintained his power by building files on numerous Washington politicians and putting his wiretapping and investigative capabilities at the service of Presidents pursuing political vendettas. That risk is making a comeback. The United States used the full force of its intelligence agencies to hold terrorism at bay for twenty years, but we paid too little attention to geopolitical adversaries who are now using chipping away at our strengths in ways we did not expect. As American intelligence reshapes itself to deal with new challenges from Russia and China, it is no longer hunting small groups of terrorists in distant deserts. -

Chapter 6: Federalists and Republicans, 1789-1816

Federalists and Republicans 1789–1816 Why It Matters In the first government under the Constitution, important new institutions included the cabinet, a system of federal courts, and a national bank. Political parties gradually developed from the different views of citizens in the Northeast, West, and South. The new government faced special challenges in foreign affairs, including the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The Impact Today During this period, fundamental policies of American government came into being. • Politicians set important precedents for the national government and for relations between the federal and state governments. For example, the idea of a presidential cabinet originated with George Washington and has been followed by every president since that time • President Washington’s caution against foreign involvement powerfully influenced American foreign policy. The American Vision Video The Chapter 6 video, “The Battle of New Orleans,” focuses on this important event of the War of 1812. 1804 • Lewis and Clark begin to explore and map 1798 Louisiana Territory 1789 • Alien and Sedition • Washington Acts introduced 1803 elected • Louisiana Purchase doubles president ▲ 1794 size of the nation Washington • Jay’s Treaty signed J. Adams Jefferson 1789–1797 ▲ 1797–1801 ▲ 1801–1809 ▲ ▲ 1790 1797 1804 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1793 1794 1805 • Louis XVI guillotined • Polish rebellion • British navy wins during French suppressed by Battle of Trafalgar Revolution Russians 1800 • Beethoven’s Symphony no. 1 written 208 Painter and President by J.L.G. Ferris 1812 • United States declares 1807 1811 war on Britain • Embargo Act blocks • Battle of Tippecanoe American trade with fought against Tecumseh 1814 Britain and France and his confederacy • Hartford Convention meets HISTORY Madison • Treaty of Ghent signed ▲ 1809–1817 ▲ ▲ ▲ Chapter Overview Visit the American Vision 1811 1818 Web site at tav.glencoe.com and click on Chapter ▼ ▼ ▼ Overviews—Chapter 6 to 1808 preview chapter information. -

Mandatory Minimum Penalties and Statutory Relief Mechanisms

Chapter 2 HISTORY OF MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES AND STATUTORY RELIEF MECHANISMS A. INTRODUCTION This chapter provides a detailed historical account of the development and evolution of federal mandatory minimum penalties. It then describes the development of the two statutory mechanisms for obtaining relief from mandatory minimum penalties. B. MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC Congress has used mandatory minimum penalties since it enacted the first federal penal laws in the late 18th century. Mandatory minimum penalties have always been prescribed for a core set of serious offenses, such as murder and treason, and also have been enacted to address immediate problems and exigencies. The Constitution authorizes Congress to establish criminal offenses and to set the punishments for those offenses,17 but there were no federal crimes when the First Congress convened in New York in March 1789.18 Congress created the first comprehensive series of federal offenses with the passage of the 1790 Crimes Act, which specified 23 federal crimes.19 Seven of the offenses in the 1790 Crimes Act carried a mandatory death penalty: treason, murder, three offenses relating to piracy, forgery of a public security of the United States, and the rescue of a person convicted of a capital crime.20 One of the piracy offenses specified four different forms of criminal conduct, arguably increasing to 10 the number of offenses carrying a mandatory minimum penalty.21 Treason, 17 See U.S. Const. art. I, §8 (enumerating powers to “provide for the Punishment of counterfeiting the Securities and current Coin of the United States” and to “define and punish Piracies and Felonies committed on the high Seas, and Offences against the Law of Nations”); U.S. -

The First and the Second

The First and the Second ____________________________ Kah Kin Ho APPROVED: ____________________________ Alin Fumurescu, Ph.D. Committee Chair ___________________________ Jeremy D. Bailey, Ph.D. __________________________ Jeffrey Church, Ph.D. ________________________________ Antonio D. Tillis, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Hispanic Studies The Second and the First, An Examination into the Formation of the First Official Political Parties Under John Adams Kah Kin Ho Current as of 1 May, 2020 2 Introduction A simple inquiry into the cannon of early American history would reveal that most of the scholarly work done on the presidency of John Adams has mostly been about two things. The first, are the problems associated with his “characteristic stubbornness” and his tendencies to be politically isolated (Mayville, 2016, pg. 128; Ryerson, 2016, pg. 350). The second, is more preoccupied with his handling of foreign relations, since Adams was seemingly more interested in those issues than the presidents before and after him (DeConde, 1966, pg. 7; Elkin and McKitrick, 1993, pg. 529). But very few have attempted to examine the correlation between the two, or even the consequences the two collectively considered would have domestically. In the following essay, I will attempt to do so. By linking the two, I will try to show that because of these two particularities, he ultimately will— however unintentionally— contribute substantially to the development of political parties and populism. In regard to his personality, it is often thought that he was much too ambitious and self- righteous to have been an ideal president in the first place. -

Fake News: National Security in the Post-Truth Era

FAKE NEWS: NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE POST-TRUTH ERA Norman Vasu, Benjamin Ang, Policy Report Terri-Anne-Teo, Shashi Jayakumar, January 2018 Muhammad Faizal, and Juhi Ahuja POLICY REPORT FAKE NEWS: NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE POST-TRUTH ERA Norman Vasu, Benjamin Ang, Terri-Anne-Teo, Shashi Jayakumar, Muhammad Faizal, and Juhi Ahuja January 2018 Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Unpacking Fake News 5 Disinformation Campaign to Undermine National Security 5 Misinformation for Domestic Political Agenda 6 Non-political Misinformation Gone Viral 7 Falsehoods for Entertainment 8 Falsehoods for Financial Gain 8 Dissemination Techniques in Disinformation Campaigns 9 Russia 9 China 12 Human Fallibility and Cognitive Predispositions 14 Fallible Memory 14 Illusory Truth Effect 15 Primacy Effect and Confirmation Bias 16 Access to Information 16 International Responses to Fake News 18 Counter Fake News Mechanisms 18 Strategic Communications 19 Self-Regulation by Technological Companies 20 Reducing Financial Incentives in Advertisements 21 Government Legislation 22 Critical Thinking and Media Literacy 24 Conclusion 26 About the Authors 29 About the Centre of Excellence for National Security 32 About the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies 32 Executive Summary Fake news is not a new issue, but it poses a greater challenge now. The velocity of information has increased drastically with messages now spreading internationally within seconds online. Readers are overwhelmed by the flood of information, but older markers of veracity have not kept up, nor has there been a commensurate growth in the ability to counter false or fake news. These developments have given an opportunity to those seeking to destabilise a state or to push their perspectives to the fore. -

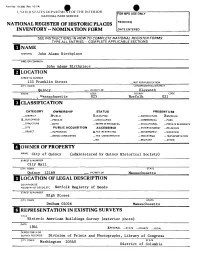

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form | Name (Owner of Property Location of Legal Description 1 Repr

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) ^M U NITbD STATES DEPARTMEm OF THE INTERIOR FOR «PS USE OHtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED. INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC John Adams Birthplace AND/OR COMMON John Adams Birthplace Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 133 Franklin Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Quincy —. VICINITY OF Eleventh STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Norfolk 021 Q CLASSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM X_BUILOING(S) _PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL _ PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS — EDUCATIONAL _ PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED _ INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME city of Quincy (administered by Quincy Historical Society) STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Quincy 12169 VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Norfolk Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER High Street CITY, TOWN STATE Dedham 02026 Massachusetts 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (exterior photo) DATE 1941 XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress __- CITY. TOWN Washington 20540 District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE — EXCELLENT _ DETERIORATED __UNALTERED JWRIGINALSITE XGOOD XALTERED __FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The John Adams Birthplace stands on the west side of Franklin Street (number 133) approximately 150 feet from its intersection with Presidents Avenue. -

The Problem Is Civil Obedience by Howard Zinn in November 1970

The Problem is Civil Obedience by Howard Zinn In November 1970, after my arrest along with others who had engaged in a Boston protest at an army base to block soldiers from being sent to Vietnam, I flew to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore to take part in a debate with the philosopher Charles Frankel on civil disobedience. I was supposed to appear in court that day in connection with the charges resulting from the army base protest. I had a choice: show up in court and miss this opportunity to explain-and practice-my commitment to civil disobedience, or face the consequences of defying the court order by going to Baltimore. I chose to go. The next day, when I returned to Boston, I went to teach my morning class at Boston University. Two detectives were waiting outside the classroom and hauled me off to court, where I was sentenced to a few days in jail. Here is the text of my speech that night at Johns Hopkins. I start from the supposition that the world is topsy-turvy, that things are all wrong, that the wrong people are in jail and the wrong people are out of jail, that the wrong people are in power and the wrong people are out of power, that the wealth is distributed in this country and the world in such a way as not simply to require small reform but to require a drastic reallocation of wealth. I start from the supposition that we don't have to say too much about this because all we have to do is think about the state of the world today and realize that things are all upside down. -

Introduction the Foundations of Diplomatic Security

INTRODUCTION THE FOUNDATIONS OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY INTRODUCTION 8 THE FOUNDATIONS OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY Diplomatic security is as old as diplomacy itself. Initially, diplomatic security was primarily the secure conveyance of government communications using couriers and codes. The Persian, Babylonian, Egyptian, Chinese, Greek, Roman, Aztec, and Incan empires developed courier services to carry imperial messages. The Greeks and Romans also developed ciphers to preserve confidentiality of diplomatic messages.1 By the Renaissance (1500s), codes had emerged, and Spanish, French, English, Vatican, and Venetian foreign ministers routinely used ciphers and codes when writing to their diplomats abroad. The European monarchies also developed courier networks to carry messages. Courier work was seen as a training ground for diplomats because couriers had to exercise discretion, know the local language, and employ disguises to avoid detection.2 Colonial-era leaders in North America were acutely aware of the need to protect their correspondence. As tensions escalated between Great Britain and its American colonies in the 1760s, the Sons of Liberty communicated with each other by Figure 1: Henry Laurens, U.S. Commissioner to the dropping letters at secretly designated coffee houses or Netherlands. Laurens and his papers were captured by the British while en route to Europe. His papers provided taverns, where sympathetic postmen or ship captains evidence of Dutch aid to the American Revolution and led would pick up and deliver the letters. During the Great Britain to declare war on the Netherlands. Portrait by Pierre Eugène du Simitière, 1783. Source: Library of American Revolution, the small fleet of sympathetic Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.