Use of Mammals in a Semi-Arid Region of Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversité Et Maladies Infectieuses: Impact Des Activités Humaines Sur Le Cycle De Transmission Des Leishmanioses En Guyane Arthur Kocher

Biodiversité et maladies infectieuses: Impact des activités humaines sur le cycle de transmission des leishmanioses en Guyane Arthur Kocher To cite this version: Arthur Kocher. Biodiversité et maladies infectieuses: Impact des activités humaines sur le cycle de transmission des leishmanioses en Guyane. Santé publique et épidémiologie. Université Toulouse 3 Paul Sabatier (UT3 Paul Sabatier), 2017. Français. tel-01764244 HAL Id: tel-01764244 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01764244 Submitted on 11 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Toulouse 3 Paul Sabatier (UT3 Paul Sabatier) Arthur Kocher le vendredi 23 juin 2017 Biodiversité et maladies infectieuses: Impact des activités humaines sur le cycle de transmission des leishmanioses en Guyane et discipline ou spécialité ED SEVAB : Écologie, biodiversité et évolution Laboratoire EDB (UMR 5174 CNRS/UPS/ENFA) Jérôme Murienne Anne-Laure Bañuls Jury: Rapporteurs: Serge Morand et Brice Rotureau Autres membres: Jérôme Chave, Jean-François Guégan et Renaud Piarroux REMERCIEMENTS Ce travail de thèse a été rendu possible par l’implication, le conseil et le soutien d’un grand nombre de personnes et d’institutions. Je tiens à remercier chaleureusement mes directeurs de thèse, Jérôme Murienne et Anne-Laure Bañuls. -

Infantum NICOLLE, 1908, Leishmania (Viannia) Braziliensis VIANNA, 1911 E ENDOPARASITOS GASTROINTESTINAIS EM ROEDORES SILVESTRES E SINANTRÓPICOS

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL RURAL DE PERNAMBUCO PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIA ANIMAL TROPICAL PESQUISA DE Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum NICOLLE, 1908, Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis VIANNA, 1911 E ENDOPARASITOS GASTROINTESTINAIS EM ROEDORES SILVESTRES E SINANTRÓPICOS VICTOR FERNANDO SANTANA LIMA RECIFE – PE 2016 0 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL RURAL DE PERNAMBUCO PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIA ANIMAL TROPICAL PESQUISA DE Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum NICOLLE, 1908, Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis VIANNA, 1911 E ENDOPARASITOS GASTROINTESTINAIS EM ROEDORES SILVESTRES E SINANTRÓPICOS VICTOR FERNANDO SANTANA LIMA “Dissertação submetida à Coordenação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência Animal Tropical, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência Animal Tropical. Orientador: Leucio Câmara Alves” RECIFE – PE 2016 1 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA L732p Lima, Victor Fernando Santana Pesquisa de Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum Nicolle, 1908, Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Vianna, 1911, e endoparasitos gastrointestinais em roedores silvestres e sinantrópicos / Victor Fernando Santana Lima. – Recife, 2016. 98 f. : il. Orientador: Leucio Câmara Alves. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência Animal Tropical) – Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal, Recife, 2016. Inclui referências e anexo(s). 1. Leishmanioses 2. Enteroparasitos 3. Roedores I. Alves, Leucio Câmara, orientador II. Título CDD 636.089 2 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL RURAL DE PERNAMBUCO PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIA ANIMAL TROPICAL Pesquisa de Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum Nicolle, 1908, Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Vianna, 1911, e endoparasitos gastrointestinais em roedores silvestres e sinantrópicos _________________________________________ Discente: Victor Fernando Santana Lima Aprovada em 22 de fevereiro de 2016. -

Advances in Cytogenetics of Brazilian Rodents: Cytotaxonomy, Chromosome Evolution and New Karyotypic Data

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogenAdvances 11(4): 833–892 in cytogenetics (2017) of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution... 833 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v11i4.19925 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Advances in cytogenetics of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution and new karyotypic data Camilla Bruno Di-Nizo1, Karina Rodrigues da Silva Banci1, Yukie Sato-Kuwabara2, Maria José de J. Silva1 1 Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução, Instituto Butantan, Avenida Vital Brazil, 1500, CEP 05503-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil 2 Departamento de Genética e Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão 277, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Corresponding author: Maria José de J. Silva ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Barabanov | Received 1 August 2017 | Accepted 23 October 2017 | Published 21 December 2017 http://zoobank.org/203690A5-3F53-4C78-A64F-C2EB2A34A67C Citation: Di-Nizo CB, Banci KRS, Sato-Kuwabara Y, Silva MJJ (2017) Advances in cytogenetics of Brazilian rodents: cytotaxonomy, chromosome evolution and new karyotypic data. Comparative Cytogenetics 11(4): 833–892. https://doi. org/10.3897/CompCytogen.v11i4.19925 Abstract Rodents constitute one of the most diversified mammalian orders. Due to the morphological similarity in many of the groups, their taxonomy is controversial. Karyotype information proved to be an important tool for distinguishing some species because some of them are species-specific. Additionally, rodents can be an excellent model for chromosome evolution studies since many rearrangements have been described in this group.This work brings a review of cytogenetic data of Brazilian rodents, with information about diploid and fundamental numbers, polymorphisms, and geographical distribution. -

Rodentia: Sigmodontinae) Com Base No Desgaste Dentário

ISSN 1808-0413 www.sbmz.org Número 86 Dezembro de 2019 (publicado em janeiro de 2020) SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE MASTOZOOLOGIA PRESIDENTES DA WWW.SBMZ.ORG SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE MASTOZOOLOGIA 2017-2019 Presidente: Paulo Sérgio D’Andrea 1985-1991 Rui Cerqueira Silva Vice-Presidente: Gisele Mendes Lessa del Giúdice 1991-1994 Maria Dalva Mello 1º Secretária: Ana Lazar Gomes e Souza 1994-1998 Ives José Sbalqueiro 2º Secretária: Fabiano Rodrigues de Melo 1998-2005 Thales Renato Ochotorena de Freitas 3º Secretário: Jorge Luiz do Nascimento 2005-2008 João Alves de Oliveira 1º Tesoureiro: Diogo Loretto Medeiros 2008-2012 Paulo Sergio D’Andrea 2º Tesoureiro: José Luis Passos Cordeiro 2012-2017 Cibele Rodrigues Bonvicino Os artigos assinados não refletem necessariamente a opinião da SBMz. As Normas de Publicação encontram-se disponíveis em versão atualizada no site da SBMz: www.sbmz.org. Ficha Catalográfica de acordo com o Código de Catalogação Anglo-Americano (AACR2). Elaborada pelo Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação do Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo. Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia. Boletim. Rio de Janeiro, RJ. Quadrimestral. Continuação de: Boletim Informativo. SBMz, n.28-39; 1994-2004; Boletim Informativo. Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia, n.1-27; 1985-94. Continua como: Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia, n.40, 2005- . ISSN 1808-0413 1. Mastozoologia. 2. Vertebrados. I. Título “Depósito legal na Biblioteca Nacional, conforme Lei n° 10.994, de 14 de dezembro de 2004”. Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia ISSN 1808-0413 Boletim da Sociedade Brasileira de Mastozoologia PUBLICAÇÃO QUADRIMESTRAL Rio de Janeiro, número 86, dezembro de 2019 (publicado em janeiro de 2020) EDITORAS Erika Hingst-Zaher – Instituto Butantan Lena Geise – Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) EDITORA EXECUTIVA Joelma Alves da Silva EDITOR EMÉRITO Rui Cerqueira Silva – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) EDITORES ASSOCIADOS Alexandra M. -

Ecologia De Kerodon Acrobata (Rodentia: Caviidae) Em Fragmentos De Mata Seca Associados a Afloramentos Calcários No Cerrado Do Brasil Central

1 Universidade de Brasília - UnB Instituto de Ciências Biológicas Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Ecologia de Kerodon acrobata (Rodentia: Caviidae) em fragmentos de mata seca associados a afloramentos calcários no Cerrado do Brasil Central Alexandre de Souza Portella Prof. Dr. Emerson Monteiro Vieira Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em Ecologia. Brasília, setembro de 2015. 2 3 Sumário Sumário ............................................................................................................................. 3 Agradecimentos ................................................................................................................. 5 Sumário de figuras ............................................................................................................ 7 Sumário de tabelas .......................................................................................................... 10 Sumário de anexos .......................................................................................................... 11 Resumo ............................................................................................................................ 12 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 14 Introdução geral ............................................................................................................... 16 Referências bibliográficas -

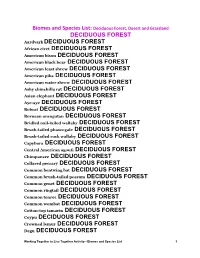

Deciduous Forest

Biomes and Species List: Deciduous Forest, Desert and Grassland DECIDUOUS FOREST Aardvark DECIDUOUS FOREST African civet DECIDUOUS FOREST American bison DECIDUOUS FOREST American black bear DECIDUOUS FOREST American least shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST American pika DECIDUOUS FOREST American water shrew DECIDUOUS FOREST Ashy chinchilla rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Asian elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Aye-aye DECIDUOUS FOREST Bobcat DECIDUOUS FOREST Bornean orangutan DECIDUOUS FOREST Bridled nail-tailed wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed phascogale DECIDUOUS FOREST Brush-tailed rock wallaby DECIDUOUS FOREST Capybara DECIDUOUS FOREST Central American agouti DECIDUOUS FOREST Chimpanzee DECIDUOUS FOREST Collared peccary DECIDUOUS FOREST Common bentwing bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Common brush-tailed possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Common genet DECIDUOUS FOREST Common ringtail DECIDUOUS FOREST Common tenrec DECIDUOUS FOREST Common wombat DECIDUOUS FOREST Cotton-top tamarin DECIDUOUS FOREST Coypu DECIDUOUS FOREST Crowned lemur DECIDUOUS FOREST Degu DECIDUOUS FOREST Working Together to Live Together Activity—Biomes and Species List 1 Desert cottontail DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern chipmunk DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern gray kangaroo DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern mole DECIDUOUS FOREST Eastern pygmy possum DECIDUOUS FOREST Edible dormouse DECIDUOUS FOREST Ermine DECIDUOUS FOREST Eurasian wild pig DECIDUOUS FOREST European badger DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest elephant DECIDUOUS FOREST Forest hog DECIDUOUS FOREST Funnel-eared bat DECIDUOUS FOREST Gambian rat DECIDUOUS FOREST Geoffroy's spider monkey -

Development of the Central Nervous System in Guinea Pig (Cavia Porcellus, Rodentia, Caviidae)1

Pesq. Vet. Bras. 36(8):753-760, agosto 2016 Development of the central nervous system in guinea pig (Cavia porcellus, Rodentia, Caviidae)1 Fernanda Menezes de Oliveira e Silva2*, Dayane Alcantara2, Rafael Cardoso Carvalho2,3, Phelipe Oliveira Favaron2, Amilton Cesar dos Santos2, Diego Carvalho Viana2 and Maria Angelica Miglino2 ABSTRACT.- Silva F.M.O., Alcantara D., Carvalho R.C., Favaron P.O., Santos A.C., Viana D.C. & Miglino M.A. 2016. Development of the central nervous system in guinea pig (Cavia porcellus, Rodentia, Caviidae). Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 36(8):753-760. Departa- mento de Cirurgia, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, Universidade de São Paulo, Av. Prof. Dr. Orlando Marques de Paiva 87, Cidade Universitária, São Paulo, SP 05508- 270, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] This study describes the development of the central nervous system in guinea pigs from 12th day post conception (dpc) until birth. Totally, 41 embryos and fetuses were analyzed macroscopically and by means of light and electron microscopy. The neural tube closure was observed at day 14 and the development of the spinal cord and differentiation of the primitive central nervous system vesicles was on 20th dpc. Histologically, undifferentiated brain tissue was observed as a mass of mesenchymal tissue between 18th and 20th dpc, and at 25th dpc the tissue within the medullary canal had higher density. On day 30 the - nal canal, period from which it was possible to observe cerebral and cerebellar stratums. Atbrain day tissue 45 intumescences was differentiated were visualizedon day 30 andand cerebralthe spinal hemispheres cord filling were throughout divided, the with spi a clear division between white and gray matter in brain and cerebellum. -

Between Species: Choreographing Human And

BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES JONATHAN OSBORN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DANCE STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY, 2019 ã Jonathan Osborn, 2019 Abstract BETWEEN SPECIES: CHOREOGRAPHING HUMAN AND NONHUMAN BODIES is a dissertation project informed by practice-led and practice-based modes of engagement, which approaches the space of the zoo as a multispecies, choreographic, affective assemblage. Drawing from critical scholarship in dance literature, zoo studies, human-animal studies, posthuman philosophy, and experiential/somatic field studies, this work utilizes choreographic engagement, with the topography and inhabitants of the Toronto Zoo and the Berlin Zoologischer Garten, to investigate the potential for kinaesthetic exchanges between human and nonhuman subjects. In tracing these exchanges, BETWEEN SPECIES documents the creation of the zoomorphic choreographic works ARK and ARCHE and creatively mediates on: more-than-human choreography; the curatorial paradigms, embodied practices, and forms of zoological gardens; the staging of human and nonhuman bodies and bodies of knowledge; the resonances and dissonances between ethological research and dance ethnography; and, the anthropocentric constitution of the field of dance studies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the glowing memory of my nana, Patricia Maltby, who, through her relentless love and fervent belief in my potential, elegantly willed me into another phase of life, while she passed, with dignity and calm, into another realm of existence. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my phenomenal supervisor Dr. Barbara Sellers-Young and my amazing committee members Dr. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

The Capybara, Its Biology and Management - J

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT - Vol. X - The Capybara, Its Biology and Management - J. Ojasti THE CAPYBARA, ITS BIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT J. Ojasti Instituto de Zoología Tropical, Facultad de Ciencias, UCV, Venezuela. Keywords: Breeding, capybara, ecology, foraging, Hydrochoerus, management, meat production, population dynamics, savanna ecosystems, social behavior, South America, wetlands. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Origin and Classification 3. General Characters 4. Distribution 5. Biological Aspects 5.1. Semi-aquatic habits 5.2. Foraging and diet 5.3. Digestion 5.4. Reproduction 5.5. Growth and Age 5.6. Behavior 6. Population Dynamics 6.1. Estimation of abundance 6.2. Population densities 6.3. Birth, mortality and production rates 7. Capybara in the Savanna Ecosystems 8. Management for Sustainable Use 8.1. Hunting and Products 8.2 Management of the Harvest 8.3. Habitat Management 8.4. Captive Breeding Glossary Bibliography BiographicalUNESCO Sketch – EOLSS Summary The capybara isSAMPLE the largest living rodent and CHAPTERS last remnant of a stock of giant rodents which evolved in South America during the last 10 million years. It is also the dominant native large herbivore and an essential component in the function of grassland ecosystems, especially floodplain savannas. Adult capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) of South American lowlands measure about 120 cm in length, 55 cm in height and weigh from 40 to 70 kg. The lesser capybara (Hydrochoerus isthmius) of Panama and the northwestern corner of South America is usually less than 100 cm in length and 30 kg in weight. Capybaras live in stable and sedentary groups of a dominant male, several females, their young, and some subordinate males. -

Acesse a Versão Em

Guia dos roedores do Brasil, com chaves para gêneros baseadas em caracteres externos C. R. Bonvicino1,2, J. A. de Oliveira 3 e P. S. D’Andrea 2 1. Programa de Genética, Instituto Nacional de Câncer, Rio de Janeiro. 2. Laboratório de Biologia e Parasitologia de Mamíferos Silvestres Reservatórios, IOC-Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro. 3. Setor de Mamíferos, Departamento de Vertebrados, Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. O conteúdo desta guia não exprime necessariamente a opinião da Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Ficha Catalográfica Bonvicino, C. R. Guia dos Roedores do Brasil, com chaves para gêneros baseadas em caracteres externos / C. R. Bonvicino, J. A. Oliveira, P. S. D’Andrea. - Rio de Janeiro: Centro Pan-Americano de Febre Aftosa - OPAS/OMS, 2008. 120 p.: il. (Série de Manuais Técnicos, 11) Bibliografia ISSN 0101-6970 1. Roedores. 2. Brasil. I. Oliveira, J. A. II. D’Andrea, P. S. III. Título. IV. Série. SUMÁRIO Prólogo ......................................................................................................07 Apresentação ........................................................................................... 09 Introdução ................................................................................................ 11 Chaves para as subordens e famílias de roedores brasileiros ............ 12 Chave para os gêneros de Sciuridae com a ocorrência no Brasil ...... 13 Gênero Sciurillus .......................................................................................................14 Gênero Guerlinguetus ...............................................................................................15 -

Major Radiations in the Evolution of Caviid Rodents: Reconciling Fossils, Ghost Lineages, and Relaxed Molecular Clocks

Major Radiations in the Evolution of Caviid Rodents: Reconciling Fossils, Ghost Lineages, and Relaxed Molecular Clocks Marı´a Encarnacio´ nPe´rez*, Diego Pol* CONICET, Museo Paleontolo´gico Egidio Feruglio, Trelew, Chubut Province, Argentina Abstract Background: Caviidae is a diverse group of caviomorph rodents that is broadly distributed in South America and is divided into three highly divergent extant lineages: Caviinae (cavies), Dolichotinae (maras), and Hydrochoerinae (capybaras). The fossil record of Caviidae is only abundant and diverse since the late Miocene. Caviids belongs to Cavioidea sensu stricto (Cavioidea s.s.) that also includes a diverse assemblage of extinct taxa recorded from the late Oligocene to the middle Miocene of South America (‘‘eocardiids’’). Results: A phylogenetic analysis combining morphological and molecular data is presented here, evaluating the time of diversification of selected nodes based on the calibration of phylogenetic trees with fossil taxa and the use of relaxed molecular clocks. This analysis reveals three major phases of diversification in the evolutionary history of Cavioidea s.s. The first two phases involve two successive radiations of extinct lineages that occurred during the late Oligocene and the early Miocene. The third phase consists of the diversification of Caviidae. The initial split of caviids is dated as middle Miocene by the fossil record. This date falls within the 95% higher probability distribution estimated by the relaxed Bayesian molecular clock, although the mean age estimate ages are 3.5 to 7 Myr older. The initial split of caviids is followed by an obscure period of poor fossil record (refered here as the Mayoan gap) and then by the appearance of highly differentiated modern lineages of caviids, which evidentially occurred at the late Miocene as indicated by both the fossil record and molecular clock estimates.