The Future of Capitalism Ranjit Sau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Documentation

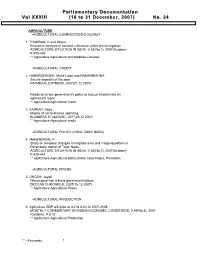

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

The Changing Face of Chinese Socialism

The Changing Face Of Chinese Socialism Xe_~v SenJice- In 1979, the United States transitioned from recognizing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People's Republic of China as the "official" China. Following the death of Mao Zedong, premier of the People's Republic of China and Chairman of the Chinese Commu- nist Party, in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to a screeching halt. Hua Guofeng became the chairman of the CCP while Deng Xiaop- eng eventually rose to the rank of Vice-premier, although Deng's role would prove more important than his title would suggest. At the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee in 1978, Deng Xiaop- eng laid the groundwork for what would become his political philos- ophy as well as the roots of what would become his economic policy, including modernizing China's economy. This paper will largely use The Beijing (Peking) Review to argue that Deng Xiaoping used for- eign-facing propaganda to sell his policy ideas to the United States and change the face of China. His goal was to abolish the Maoist pol- icy of continuous revolution which had caused such a lack of confi- dence in China; Deng's policy was to move forward to a more predict- able China, one in which foreign investments would be safe. The economic reforms instituted by Deng during the 1980s served primarily to modernize China's economy and transition from purely agrarian-centered economic policy to a hybrid economy that emphasized a balance of all aspects of the economy. However, there was also a foreign policy aspect to Deng's new economic policy. -

Modern China Hist3433 Syllabus – Spring 2016 COURSE

Modern China Hist3433 Syllabus – Spring 2016 COURSE INSTRUCTOR Instructor: Ihor Pidhainy Office: TLC 3245 Phone: 678-839-6508 Email: [email protected] Class: Social Science Building 206 MW 3:30-4:50 Best Way to reach me: email me at the above email, and I’ll get back to you within 24 hours. (First semester for me too, so I might be slow with courseden replies… it will improve by the end of semester…) OFFICE HOURS MW 2:00-3:00 OR: by appointment Nota Bene: Office hours are usually a lonely time, especially when there isn’t an essay/test immediately due. If you come by and want to talk about the course or some aspect of what we’re doing or just cause you need to talk with somebody about history or Asia etc., you are most welcome. Required Texts: Chen, Janet et al. The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection 978-0-393-92085-7 3rd edition wwnorton Feng, Jicai, Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of China's Cultural Revolution 978-0835125840 China Books and Periodicals Hawkes, David Story of the Stone: or The Dream of the Red Chamber v. 1 978-0140442939 Penguin Mitter, Rana Modern China: A very short introduction 978-0199228027 Oxford UP Tanner, Harold, China: A History V 2. From the Great Qing Empire through The People's Republic of China, (1644 - 2009) 978-1-60384-204-4 Hackett Yu, Hua, China in Ten Words 978-0307739797 vintage http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/opium_wars_01/ow1_essay.pdf Course Description This course is an exploration of modern Chinese history, focusing on the period from 1840 to the present. -

Changes of the Chinese Communist Party's Ideology and Reform Since

Changes of the Chinese Communist Party’s Ideology and Reform Since 1978 Author Zhou, Shanding Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3255 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366150 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Changes of the Chinese Communist Party’s Ideology and Reform Since 1978 Shanding Zhou Master of Asian Studies, Griffith University International Business & Asian Studies Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 i ii Synopsis The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s ideology has undergone remarkable changes in the past three decades which have facilitated China’s reform and opening up as well as its modernization. The thesis has expounded upon the argumentation by enumerating five dimensions of CCP’s ideological changes and development since 1978. First, the Party had restructured its ideological orthodoxy, advocating of ‘seeking truth from facts.’ Some of central Marxist tenets, such as ‘class struggle’, have been revised, and in effect demoted, and the ‘productive forces’ have been emphasized as the motive forces of history, so that the Party shifted its prime attention to economic development and socialist construction. The Party theorists proposed treating Marxism as a ‘developing science’ and a branch of the social sciences, but not an all-encompassing ‘science of sciences.’ These efforts have been so transformative that they have brought revolutionary changes in Chinese thinking of, and approach to Marxism. -

Constitution of the Communist Party of China

CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF CHINA Revised and adopted at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China on October 24, 2017 General Program The Communist Party of China is the vanguard of the Chinese working class, the Chinese people, and the Chinese nation. It is the leadership core for the cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics and represents the developmental demands of China’s advanced productive forces, the orientation for China’s advanced culture, and the fundamental interests of the greatest possible majority of the Chinese people. The Party’s highest ideal and ultimate goal is the realization of communism. The Communist Party of China uses Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, the Scientific Outlook on Development, and Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era as its guides to action. Marxism-Leninism reveals the laws governing the development of the history of human society. Its basic tenets are correct and have tremendous vitality. The highest ideal of communism pursued by Chinese Communists can be realized only when socialist society is fully developed and highly advanced. The development and improvement of the socialist system is a long historical process. By upholding the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism and following the path suited to China’s specific conditions as chosen by the Chinese people, China’s socialist cause will ultimately be victorious. With Comrade Mao Zedong as their chief representative, Chinese Communists developed Mao Zedong Thought by combining the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism with the actual practice of the Chinese revolution. -

Seeking Truth from Facts’

Pragmatics 19:2.223-239 (2009) International Pragmatics Association DISCOURSE AS COMMUNICATIVE ACTION: VALIDATION OF CHINA’S NEW SOCIO-CULTURAL PARADIGM QIYE WENHUA/‘ENTERPRISE CULTURE’ Song Mei Lee-Wong Abstract Qiye wenhua/’enterprise culture’ has emerged as a new paradigm in China’s economic reforms. Hailed as China’s new ‘culture’ it featured in an interview with certain executives of non-state owned enterprises. In the examination of this discourse, the concept of ‘communicative action’ (Habermas, 1998) is adopted as an analytical tool. The main contention in this exploratory examination is that there is speaker intent to justify China’s model of socialist market economy. This justification is mainly reflected in the semantic content of the discourse, which stresses what is ‘unique’ and ‘characteristic’ in China’s economic reforms. The rationale for this contention rests primarily on the argument that given the context of skepticism and criticisms leveled at the Chinese model, and the fact that the speakers themselves are key players in the new market economy, it would be likely that in a public discourse of this nature there would be grounds for attempts at legitimizing the Chinese economic model. Keywords: Communicative action; Communicative rationality; Socio-cultural paradigm; Social reality; Lifeworld; Public sphere; Internal reality; External reality; Normative reality. Introduction and background Communication remains the single most vital instrument to reach understanding with the masses in China, in particular to allay their fear of being left behind as China continues to prosper in the march towards marketization. President Hu Jintao in a speech on meeting “the requirements of building a moderately prosperous society in all aspects” gives this assurance: “We shall fully implement the concept of putting people first. -

Negotiating History: the Chinese Communist Party's 1981

Negotiating History: The Chinese Communist Party’s 1981 “Resolution on certain questions in the history of our party since the founding of the People’s Republic of China” Robert L. Suettinger July 17, 2017 About the Project 2049 Institute The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. Located in Arlington, Virginia, the organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region-specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological, and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. About the Author Robert L. Suettinger is an analyst and expert on issues pertaining to Chinese politics, and recently served as Senior Advisor and Consultant at the Stimson Center. Prior to joining Stimson, he was an Analytic Director at CENTRA Technology, Inc. for nine years. Previously, he was Director of Research for MBP Consulting Limited LLC, a Senior Policy Analyst at RAND, and a Visiting Fellow at the Brookings Institution. Suettinger retired from federal government service in 1998, after nearly 25 years in the intelligence and foreign policy bureaucracies. He joined the Central Intelligence Agency in 1975, and spent his entire career in the analysis of Asian affairs. After several years as an analyst and manager in the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence, he was assigned as Director of the Office of Analysis for East Asia and the Pacific in the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. -

Challenges and Opportunities in the Brazil-Asia Relationship in the Perspective of Young Diplomats

Relações coleção coleção Internacionais Challenges and opportunities in the Brazil-Asia relationship in the perspective of young diplomats Ministry of Foreign Affairs Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation The Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation – FUNAG, established in 1971, is a public foundation linked to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs whose goal is to provide civil society with information concerning the international scenario and aspects of the Brazilian diplomatic agenda. The Foundation’s mission is to foster awareness of the domestic public opinion with regard to international relations issues and Brazilian foreign policy. FUNAG is headquartered in Brasília, Federal District, and has two units in its structure: the International Relations Research Institute – IPRI, and the Center for History and Diplomatic Documentation – CHDD, the latter being located in Rio de Janeiro. (Editor) Pedro Henrique Batista Barbosa Challenges and opportunities in the Brazil-Asia relationship in the perspective of young diplomats Brasília – 2019 Copyright ©Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation Ministry of Foreign Affairs Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H, Anexo II, Térreo 70170-900 Brasília-DF Phone numbers: +55 (61) 2030-9117/9128 Website: www.funag.gov.br E-mail: [email protected] Editorial staff: Eliane Miranda Paiva André Luiz Ventura Ferreira Gabriela Del Rio de Rezende Luiz Antônio Gusmão Guilherme Lucas Rodrigues Monteiro Graphic design and cover: Varnei Rodrigues / Propagare Comercial Ltda. Originally published as “Os desafios e oportunidades na relação Brasil-Ásia na perspectiva de jovens diplomatas”, FUNAG, 2017. The opinions expressed in this work are solely the authors’ personal views and do not necessarily state or reflect those of the Brazilian government’s foreign policy. -

Minami-Mastersreport-2014

Copyright by Kazushi Minami 2014 The Report committee for Kazushi Minami certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Toward Strategic Alignment: Sino-American Relations from Rapprochement to Normalization APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: ———————————————————— Jeremi Suri, Supervisor ———————————————————— Huaiyin Li Toward Strategic Alignment: Sino-American Relations from Rapprochement to Normalization by Kazushi Minami, B.ECO. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December, 2014 Toward Strategic Alignment: Sino-American Relations from Rapprochement to Normalization by Kazushi Minami, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2014 SUPERVISOR: Jeremi Suri Richard Nixon’s trip to China in February 1972 marked a diplomatic breakthrough for Sino-American relations after two decades of mutual animosity since the Korean War. Nevertheless, the bilateral relations underwent a long stalemate in the mid-1970s, before the United States and China finally reached normalization of relations in December 1978. The scholarship on Sino-American relations in the 1970s tends to focus on Nixon’s visit or normalization of relations, without paying adequate attention to how Washington and Beijing dealt with the mid-decade deadlock. My report addresses this gap in the literature by analyzing the changing dynamism of Sino-American relations, determined first by Henry Kissinger and Mao Zedong, and later by Zbigniew Brzezinski and Deng Xiaoping. Kissinger sought to establish a triangular relationship with the Soviet Union and China, where the United States could manipulate the Sino-Soviet antagonism to improve its relations with both communist giants. -

June 27, 1981 Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People’S Republic of China

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June 27, 1981 Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China Citation: “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China,” June 27, 1981, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Translation from the Beijing Review 24, no. 27 (July 6, 1981): 10-39. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121344 Summary: The Chinese Communist Party assesses the legacy and shortcomings of Mao Zedong, criticizes the Cultural Revolution, and calls for Party unity going forward. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Chinese Transcription Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China (Adopted by the Sixth Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on June 27, 1981) Review of the History of the Twenty-Eight Years Before the Founding of the People’s Republic 1. The Communist Party of China has traversed sixty years of glorious struggle since its founding in 1921. In order to sum up its experience in the thirty-two years since the founding of the People’s Republic, we must briefly review the previous twenty-eight years in which the Party led the people in waging the revolutionary struggle for New Democracy. 2. The Communist Party of China was the product of the integration of Marxism-Leninism with the Chinese workers’ movement and was founded under the influence of the October Revolution in Russia and the May 4th Movement in China and with the help of the Communist International led by Lenin.