Minami-Mastersreport-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Documentation

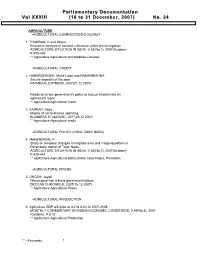

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

Submitted for the Phd Degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

THE CHINESE SHORT STORY IN 1979: AN INTERPRETATION BASED ON OFFICIAL AND NONOFFICIAL LITERARY JOURNALS DESMOND A. SKEEL Submitted for the PhD degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1995 ProQuest Number: 10731694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731694 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A b s t ra c t The short story has been an important genre in 20th century Chinese literature. By its very nature the short story affords the writer the opportunity to introduce swiftly any developments in ideology, theme or style. Scholars have interpreted Chinese fiction published during 1979 as indicative of a "change" in the development of 20th century Chinese literature. This study examines a number of short stories from 1979 in order to determine the extent of that "change". The first two chapters concern the establishment of a representative database and the adoption of viable methods of interpretation. An important, although much neglected, phenomenon in the make-up of 1979 literature are the works which appeared in so-called "nonofficial" journals. -

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Documents Anhui tongzhi gao 安徽通志稿 [The Draft of Comprehensive Gazetteer of Anhui Province]. Bao Shichen 包世臣. Anwu sizhong 安四种 [Four Writings of Anwu]. Bian Baodi 卞宝弟. Bian Zhijun zouyi 卞制军奏议 [Memorials of Bian Zhijun]. Chen Bangzhan 陈邦瞻. Songshi jishi benmo 宋史纪事本末 [The Separate and Full Account of Events in Song Dynasty]. Chen Zhida 陈智达. Sanjiao chuxue zhinan 三教初学指南 [Guide for Beginner of the Teaching of Three Doctrines]. Chen Zhongyu 陈衷瑜. Chenzi huigui 陈子会规 [Rules Proposed by the Master Chen]. Damingxian zhailonghua cun diaocha ziliao 大名县翟龙化村调查材料 [Materials Collected in Fieldwork in the Zhailonghua Village of Daming County]. Dayu ji 大狱记 [Great Inquisitions]. Ding Bin 丁宾. Ding qinghui gong yiji 丁清惠公遗集 [The Posthumous Collection of Writings of Ding Bin, the Lord of Cleanness and Beneficence]. Dong Shi 董史. Dongshan jicao 东山集草 [Writing Collections of the Notables]. Donghua lu 东华录 [The Donghua Annals]. Du You 杜佑. Tong dian 通典 [Encyclopedia for Institutions]. Foshuo sanhui jiuzhuan xiasheng caoxi baojuan 佛说三回九转下生漕溪宝卷 [The Precious Scroll of Twisty Descending down upon Caoxi As the Buddha Says]. Foshuo wuwei jindan jianyao keyi baojuan 佛说无为金丹拣要科仪宝卷 [The Precious Scroll of Essential Rules of None-Action Golden Elixir As the Buddha Says]. Gao Ju 高举 et al. Da Ming lü jijie 大明律集解 [Collected Commentaries on The Great Ming Code]. Gaokou cun diaocha ziliao 高口村调查资料 [Materials Collected in Fieldwork in the Gaokou Village]. Guanxian duo’erzhuang diaocha ziliao 冠县垛儿庄调查资料 [Materials Collected in Field- work in the Duoerzhuang Village of Guan County]. Guanxian xusanli zhuang diaocha cailiao 冠县徐三里庄调查材料 [Materials Collected in Fieldwork in the Xusanli Village of Guan County]. Guo Jianling 郭篯龄. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

China's Lost Decade'

Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade” Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade”. China’s Lost Decade: Cultural Politics and Poetics 1978-1990 - In Place of History, Tigre de Papier, 391 p., 2009. hal- 00385268 HAL Id: hal-00385268 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00385268 Submitted on 21 May 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHINA©S LOST DECADE CULTURAL POLITICS AND POETICS 1978-1990 IN PLACE OF HISTORY Gregory B. Lee Tigre de Papier In memory of Paola Sandri 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................. 7 PREAMBLE ............................................... 11 THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT ................... 12 INTRODUCTION ........................................ 18 THE BEGINNING OF THE 'LOST DECADE' ............................................................. 19 THE END OF THE DECADE .................... 33 LANGUAGE OF THE DECADE ................ 36 BEING THERE ....................................... -

Mao's Failure, Deng's Success

MAO'S FAILURE, DENG'S SUCCESS Roderick MacFarquhar Professor of History and Political Science, Harvard University June 24, 2010 Revolutionaries have to be optimists as well as believers, and revolutionary leaders have to be able to inspire their followers, convince them that "Yes, we can!" How could they endure years of struggle on a long march towards a seemingly ever-receding promised land without believing, as Mao Zedong put it during the darkest days of the Chinese revolution, that "a single spark can start a prairie fire?" During the anti-Japanese war, Mao laid down that in the aftermath of defeat, a communist should correct his ideas "to make them correspond to the laws of the external world, and thus turn failure into success; this is what is meant by 'failure is the mother of success' and 'a fall into the pit, a gain in your wit."1 Twenty years later, during the upheaval within international communism brought about by Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin and the subsequent Hungarian revolt, Mao remained determinedly optimistic, claiming that bad things can be turned into good things ... In given conditions, a bad thing can lead to good results and a good thing to bad results. More than two thousand years ago Lao Tzu said: "Good fortune lieth within bad, bad fortune lurketh within good."2 Alas for Mao, not only was Lao Tzu right, but, more importantly, Mao's countrymen and his successors did not agree with him as to what constituted good and bad things. On his deathbed, Mao claimed that the Cultural Revolution was one of his two major lifetime achievements, the other being the victory that brought the communists to power in 1949.3 But within the utopian vision of Mao's Cultural Revolution, egalitarian and collectivist though it was, lurked the seeds of its antithesis, the Chairman's bête noire, the helter- skelter capitalism of the Deng Xiaoping era. -

The Changing Face of Chinese Socialism

The Changing Face Of Chinese Socialism Xe_~v SenJice- In 1979, the United States transitioned from recognizing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People's Republic of China as the "official" China. Following the death of Mao Zedong, premier of the People's Republic of China and Chairman of the Chinese Commu- nist Party, in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to a screeching halt. Hua Guofeng became the chairman of the CCP while Deng Xiaop- eng eventually rose to the rank of Vice-premier, although Deng's role would prove more important than his title would suggest. At the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee in 1978, Deng Xiaop- eng laid the groundwork for what would become his political philos- ophy as well as the roots of what would become his economic policy, including modernizing China's economy. This paper will largely use The Beijing (Peking) Review to argue that Deng Xiaoping used for- eign-facing propaganda to sell his policy ideas to the United States and change the face of China. His goal was to abolish the Maoist pol- icy of continuous revolution which had caused such a lack of confi- dence in China; Deng's policy was to move forward to a more predict- able China, one in which foreign investments would be safe. The economic reforms instituted by Deng during the 1980s served primarily to modernize China's economy and transition from purely agrarian-centered economic policy to a hybrid economy that emphasized a balance of all aspects of the economy. However, there was also a foreign policy aspect to Deng's new economic policy. -

Huang Zhen (黄 振), PU Wen-Yao 3 (濮文耀)

Vol.16 No.1 JOURNAL OF TROPICAL METEOROLOGY March 2009 Article ID: 1006-8775(2010) 01-077-05 VERIFICATION OF TYPHOON FORECASTS BY THE GRAPES MODEL 1 2 1 SONG Yv (宋 煜), YE Cheng-zhi (叶成志) , Huang Zhen (黄 振), PU Wen-yao 3 (濮文耀) (1. Dalian Meteorological Observatory, Dalian 116001 China; 2. Hunan Meteorological Observatory, Changsha 410007 China; 3. Dalian Weather Modification Office, Dalian 116001 China) Abstract: Four landfalling typhoon cases in 2005 were selected for a numerical simulation study with the Global/Regional Assimilation and Prediction System (GRAPES) model. The preliminary assessment results of the performance of the model, including the predictions of typhoon track, landfall time, location and intensity, etc., are presented and the sources of errors are analyzed. The 24-hour distance forecast error of the typhoon center by the model is shown to be about 131 km, while the 48-hour error is 252 km. The model was relatively more skilful at forecasts of landfall time and locations than those of intensity at landfall. On average, the 24-hour forecasts were slightly better than the 48-hour ones. An analysis of data impacts indicates that the assimilation of unconventional observation data is essential for the improvement of the model simulation. The model could also be improved by increasing model resolution to simulate the mesoscale and fine scale systems and by improving methods of terrain refinement processing. Key words: GRAPES model; landfalling typhoon; verification CLC number: P444 Document code: A doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-8775.2010.01.011 1 INTRODUCTION errors of typhoon paths issued by the Central Meteorological Observatory of China were 120 km Landfalls of typhoons in 2005 were and 198 km, respectively.