China's Lost Decade'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Mao's Failure, Deng's Success

MAO'S FAILURE, DENG'S SUCCESS Roderick MacFarquhar Professor of History and Political Science, Harvard University June 24, 2010 Revolutionaries have to be optimists as well as believers, and revolutionary leaders have to be able to inspire their followers, convince them that "Yes, we can!" How could they endure years of struggle on a long march towards a seemingly ever-receding promised land without believing, as Mao Zedong put it during the darkest days of the Chinese revolution, that "a single spark can start a prairie fire?" During the anti-Japanese war, Mao laid down that in the aftermath of defeat, a communist should correct his ideas "to make them correspond to the laws of the external world, and thus turn failure into success; this is what is meant by 'failure is the mother of success' and 'a fall into the pit, a gain in your wit."1 Twenty years later, during the upheaval within international communism brought about by Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin and the subsequent Hungarian revolt, Mao remained determinedly optimistic, claiming that bad things can be turned into good things ... In given conditions, a bad thing can lead to good results and a good thing to bad results. More than two thousand years ago Lao Tzu said: "Good fortune lieth within bad, bad fortune lurketh within good."2 Alas for Mao, not only was Lao Tzu right, but, more importantly, Mao's countrymen and his successors did not agree with him as to what constituted good and bad things. On his deathbed, Mao claimed that the Cultural Revolution was one of his two major lifetime achievements, the other being the victory that brought the communists to power in 1949.3 But within the utopian vision of Mao's Cultural Revolution, egalitarian and collectivist though it was, lurked the seeds of its antithesis, the Chairman's bête noire, the helter- skelter capitalism of the Deng Xiaoping era. -

Petroleum Group’S Rise to Power

1 Shifting development Strategies in Post-Maoist China : A Research into the Interplay of Politics and Economic Strategy (1976-1979) Ari Van Assche August 1999 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction 1. Historic Background 2.1 The Petroleum Group’s Rise to Power 2.2 Decentralization during the Turbulent Years of the Cultural Revolution 2.3 Recentralisation of Economic Decision-Making Power 2.4 The Petroleum Group Discredited 2.5 Conclusion 2. Rise to Power of the Military-Bureaucratic Coalition 2.1 Politicial Model 2.2 Political Landscape 2.3 Collaboration of the Survivors and Beneficiaries 2.4 Military-bureaucratic coalition 2.5 Rehabilitation of Deng Xiaoping (Breach of Harmony) 2.6 Conclusion 3. Four Modernizations Program 3.1 Economic situation during the Cultural Revolution 3.2 Recentralisation of economic decision-making power 3.3 Four Modernisations Program 3.4 Ten-Year Plan 3 3.5 Great Leap Outward 3.6 Conclusion 4. Economic Imbalances 4.1 External Imbalance 4.2 Internal Imbalance 4.3 Conclusion 5. Political Struggle 5.1 Political Landscape 5.2 Practice Faction in control of the media 5.3 Regional support for the practice faction 5.4 November Work Conference – finishing off the Whatever Faction 5.5 Conclusion 6. Retrenchment Strategy 6.1 Rise of Chen Yun 6.2 Abolishment of the Ten-Year Plan 6.3 Retrenchment Strategy 7.1 Conclusion 7. Conclusion 8. Bibliography 4 INTRODUCTION The spectacular growth of the Chinese economy from the beginning of the 1980s to the present day has fascinated many scholars. Puzzled by the reasons behind the breath-taking speed of this economic take-off, they initiated profound analyses of the fundamental political and economic logic behind this phenomenon. -

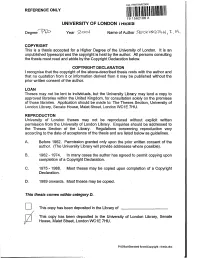

University of London Ihesis

19 1562106X UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IHESIS DegreeT^D^ Year2o o\ Name of Author5&<Z <2 (NQ-To N , T. COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTON University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

The Communist Party of China: I • Party Powers and Group Poutics I from the Third Plenum to the Twelfth Party Congress

\ 1 ' NUMBER 2- 1984 (81) NUMBER 2 - 1984 (81) THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF CHINA: I • PARTY POWERS AND GROUP POUTICS I FROM THE THIRD PLENUM TO THE TWELFTH PARTY CONGRESS Hung-mao Tien School of LAw ~ of MAaylANCI • ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Mitchell A. Silk Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, Lafayette College Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, College of Law and East Asian Law of the Sea Institute, Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. -

Changes of the Chinese Communist Party's Ideology and Reform Since

Changes of the Chinese Communist Party’s Ideology and Reform Since 1978 Author Zhou, Shanding Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3255 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366150 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Changes of the Chinese Communist Party’s Ideology and Reform Since 1978 Shanding Zhou Master of Asian Studies, Griffith University International Business & Asian Studies Griffith Business School Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 i ii Synopsis The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s ideology has undergone remarkable changes in the past three decades which have facilitated China’s reform and opening up as well as its modernization. The thesis has expounded upon the argumentation by enumerating five dimensions of CCP’s ideological changes and development since 1978. First, the Party had restructured its ideological orthodoxy, advocating of ‘seeking truth from facts.’ Some of central Marxist tenets, such as ‘class struggle’, have been revised, and in effect demoted, and the ‘productive forces’ have been emphasized as the motive forces of history, so that the Party shifted its prime attention to economic development and socialist construction. The Party theorists proposed treating Marxism as a ‘developing science’ and a branch of the social sciences, but not an all-encompassing ‘science of sciences.’ These efforts have been so transformative that they have brought revolutionary changes in Chinese thinking of, and approach to Marxism. -

December 13, 1978 Hua Guofeng's Speech at the Closing Session of the CCP Central Work Conference

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified December 13, 1978 Hua Guofeng's Speech at the Closing Session of the CCP Central Work Conference Citation: “Hua Guofeng's Speech at the Closing Session of the CCP Central Work Conference,” December 13, 1978, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Hubei Provincial Archives SZ1-4-791. Translated by Caixia Lu. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/121690 Summary: Hua Guofeng reflects on the conclusion of the 1978 Central Committee Work Conference, and describes his policy of the "two whatevers," or the decision to uphold Mao Zedong's policies and instructions. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Speech at the Closing Session of the Central Committee Work Conference (13 December 1978) Hua Guofeng Comrades: Comrade Deng Xiaoping and Comrade Ye Jianying had made important speeches earlier. I fully agree with their points. Our present work conference, which began in November, has been in session for 34 days. Today, we are having the closing session, after which there will be two more days of discussions before the meeting comes to a victorious conclusion. It is the unanimous view of our comrades in the Central Politburo and all comrades present that the principle of democratic centralism has been upheld throughout the conference, and we have managed to implement the method of “criticism-unity-criticism”, fully embrace the spirit of democracy, enable everyone to speak freely and tap the collective wisdom. This conference has been a very good and successful one thanks to the common effort of all comrades in attendance. -

“A Community of Shared Destiny” How China Is Reshaping Human Rights in Southeast Asia

ema Awarded Theses 2018/2019 Álvaro Gómez del Valle Ruiz “A Community of Shared Destiny” How China Is Reshaping Human Rights in Southeast Asia ema, The European Master’s Programme in Human Rights and Democratisation ÁLVARO GÓMEZ DEL VALLE RUIZ “A COMMUNITY OF SHARED DESTINY” HOW CHINA IS RESHAPING HUMAN RIGHTS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ÁLVARO GÓMEZ DEL VALLE RUIZ FOREWORD The European Master’s Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation (EMA) is a one-year intensive programme launched in 1997 as a joint initiative of universities in all EU Member States with support from the European Commission. Based on an action- and policy-oriented approach to learning, it combines legal, political, historical, anthropological and philosophical perspectives on the study of human rights and democracy with targeted skills- building activities. The aim from the outset was to prepare young professionals to respond to the requirements and challenges of work in international organisations, field operations, governmental and non-governmental bodies, and academia. As a measure of its success, EMA has served as a model of inspiration for the establishment of six other EU-sponsored regional master’s programmes in the area of human rights and democratisation in different parts of the world. These programmes cooperate closely in the framework of the Global Campus of Human Rights, which is based in Venice, Italy. Ninety students are admitted to the EMA programme each year. During the first semester in Venice, students have the opportunity to meet and learn from leading academics, experts and representatives of international and non-governmental organisations. During the second semester, they relocate to one of the 41 participating universities to follow additional courses in an area of specialisation of their own choice and to conduct research under the supervision of the resident EMA Director or other academic staff. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Reflecting the Chinese revolution at that time, the infamous legacy of Mao Zedong, successfully turns China to be a communist country. Mao had transformed China from the failed experience of China’s failure in the Opium war against Japan and the European powers1. The abolition of class society was the first step in entering the new ideological era of China, which is communism. After that, China became a very closed state in relation with foreign nations. However, millions of Chinese suffered under his policies because there was a limited access of the daily basic needs2. The government had mass control over the society, which created a depreciation of freedom. An example that showed the aforementioned was the great leap policy created by Mao, which enforced civilians to produce steal and grain in a exaggerating manner, and eventually killing 45 million people in four years3. Furthermore, the legacy of Mao continued to the next third generation. During the transitional time between the deaths of Mao Zedong in 1976 with the reformation of China by Deng Xiaoping in 1981, the third leader who was in power (Hua Guofeng) strongly pursued Mao’s “Two Whatevers” policy, that stated: “We 1 Chinasage, “Chinese Leaders 1949 to the present day”, http://www.chinasage.info/leaders.htm. (accessed October 15, 2015). 2 Ibid. 3 Arifa Akbar, "Mao's Great Leap Forward 'killed 45 Million in Four Years,'" The Independent, http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/news/maos-great-leap-forward-killed-45- million-in-four-years-2081630.html. -

Petitioning for Redress Over the Anti-Rightist Campaign

PETITIONING FOR REDRESS OVER THE ANTI-RIGHTIST CAMPAIGN In the run-up to the fiftieth anniversary of the Anti-Rightist Campaign, an increasing number of public petitions have been circulated, gathering public support for official accountability on the issue. Following are two such petitions. The first, initiated in Shandong in 2005, has attracted thousands of signatures worldwide. Petition for redress to those wrongfully labeled rightists Addressed to the CCP Central Committee, the NPC and the State Council Organizer: Surviving victims of the Anti-Rightist Campaign and their families Initiation Date: 11/13/2005 Cut-off date: open Forty-eight years ago, in 1957, Mao Zedong spear-headed the rectification and anti- rightist campaign. Twenty-six years ago, in 1979, the rightist label was “corrected,” and the officially acknowledged number of rightists was adjusted to around 550,000 , an obvious reduction . Not included in that number were those labeled during the same period as counterrevolutionaries , traitors and anti-Party elements, and moderate right - ists .1 Also not included were many who, on returning from Reeducation-Through- Labor (RTL) to have their cases reexamined and amended, were found never to have actually been labeled as rightists, although they had been persecuted as such for 22 years. During the reexamination of rightist cases in 1979, reassessment was still based on the “six criteria” used during the Anti-Rightist Movement ,2 but it was ultimately determined that over 99 percent of “rightists ”had been wrongly labeled, and only a few “classic exam - ples” were not rehabilitated in order to maintain the conclusion that “the Anti-Rightist Campaign was a necessary step that got out of hand.” Even so, the figure of more than 550,000 rightists amounted to over 10 percent of the total number of intellectuals at the PETITIONING FOR REDRESS OVER THE ANTI-RIGHTIST CAMPAIGN | 179 Anti-Rightist campaign victim Yan Dunfu (L) displays a copy of the protest poster that led to her purg - ing.