December 13, 1978 Hua Guofeng's Speech at the Closing Session of the CCP Central Work Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 12, 1967 Discussion Between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 12, 1967 Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap Citation: “Discussion between Zhou Enlai, Chen Yi, Pham Van Dong and Vo Nguyen Giap,” April 12, 1967, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Working Paper 22, "77 Conversations." http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112156 Summary: Zhou Enlai discusses the class struggle present in China. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation ZHOU ENLAI, CHEN YI AND PHAM VAN DONG, VO NGUYEN GIAP Beijing, 12 April 1967 Zhou Enlai: …In the past ten years, we were conducting another war, a bloodless one: a class struggle. But, it is a matter of fact that among our generals, there are some, [although] not all, who knew very well how to conduct a bloody war, [but] now don’t know how to conduct a bloodless one. They even look down on the masses. The other day while we were on board the plane, I told you that our cultural revolution this time was aimed at overthrowing a group of ruling people in the party who wanted to follow the capitalist path. It was also aimed at destroying the old forces, the old culture, the old ideology, the old customs that were not suitable to the socialist revolution. In one of his speeches last year, Comrade Lin Biao said: In the process of socialist revolution, we have to destroy the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie, and to construct the “public ownership” of the proletariat. So, for the introduction of the “public ownership” system, who do you rely on? Based on the experience in the 17 years after liberation, Comrade Mao Zedong holds that after seizing power, the proletariat should eliminate the “private ownership” of the bourgeoisie. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

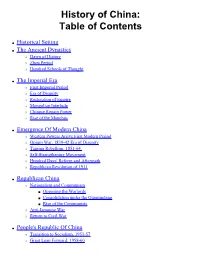

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

From" Morning Sun" To" Though I Was Dead": the Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident"

From" Morning Sun" to" Though I Was Dead": The Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident" Wei-li Wu, Taipei College of Maritime Technology, Taiwan The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2016 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This year is the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. On August 5, 1966, Bian Zhongyun, the deputy principal at the girls High School Attached to Beijing Normal University, was beaten to death by the students struggling against her. She was the first teacher killed in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and her death had established the “violence” nature of the Cultural Revolution. After the Cultural Revolution, the reminiscences, papers, and comments related to the “August Fifth Incident” were gradually introduced, but with all blames pointing to the student leader of that school, Song Binbin – the one who had pinned a red band on Mao Zedong's arm. It was not until 2003 when the American director, Carma Hinton filmed the Morning Sun that Song Binbin broke her silence to defend herself. However, voices of attacks came hot on the heels of her defense. In 2006, in Though I Am Gone, a documentary filmed by the Chinese director Hu Jie, the responsibility was once again laid on Song Binbin through the use of images. Due to the differences in perception between the two sides, this paper subjects these two documentaries to textual analysis, supplementing it with relevant literature and other information, to objectively outline the two different images of Song Binbin in the “August Fifth Incident” as perceived by people and their justice. -

Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 25 Xi Jinping and the Party Apparatus Alice Miller In the six months since the 17th Party Congress, Xi Jinping’s public appearances indicate that he has been given the task of day-to-day supervision of the Party apparatus. This role will allow him to expand and consolidate his personal relationships up and down the Party hierarchy, a critical opportunity in his preparation to succeed Hu Jintao as Party leader in 2012. In particular, as Hu Jintao did in his decade of preparation prior to becoming top Party leader in 2002, Xi presides over the Party Secretariat. Traditionally, the Secretariat has served the Party’s top policy coordinating body, supervising implementation of decisions made by the Party Politburo and its Standing Committee. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Xi’s Secretariat has been significantly trimmed to focus solely on the Party apparatus, and has apparently relinquished its longstanding role in coordinating decisions in several major sectors of substantive policy. Xi’s Activities since the Party Congress At the First Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party’s 17th Central Committee on 22 October 2007, Xi Jinping was appointed sixth-ranking member of the Politburo Standing Committee and executive secretary of the Party Secretariat. In December 2007, he was also appointed president of the Central Party School, the Party’s finishing school for up and coming leaders and an important think-tank for the Party’s top leadership. On 15 March 2008, at the 11th National People’s Congress (NPC), Xi was also elected PRC vice president, a role that gives him enhanced opportunity to meet with visiting foreign leaders and to travel abroad on official state business. -

Download the Publication

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, 77 CONVERSATIONS Christian Ostermann, Director Director Between Chinese and Foreign Leaders on the Wars in Indochina, 1964-1977 BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY Edited by COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., Chairman Odd Arne Westad, Chen Jian, Stein Tønnesson, William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, (Amherst College) Nguyen Vu Tungand and James G. Hershberg Vice Chairman Chairman PUBLIC MEMBERS Working Paper No. 22 Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen (University of Maryland- The Chairman of the National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, May 1998 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

China's Lost Decade'

Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade” Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade”. China’s Lost Decade: Cultural Politics and Poetics 1978-1990 - In Place of History, Tigre de Papier, 391 p., 2009. hal- 00385268 HAL Id: hal-00385268 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00385268 Submitted on 21 May 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHINA©S LOST DECADE CULTURAL POLITICS AND POETICS 1978-1990 IN PLACE OF HISTORY Gregory B. Lee Tigre de Papier In memory of Paola Sandri 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................. 7 PREAMBLE ............................................... 11 THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT ................... 12 INTRODUCTION ........................................ 18 THE BEGINNING OF THE 'LOST DECADE' ............................................................. 19 THE END OF THE DECADE .................... 33 LANGUAGE OF THE DECADE ................ 36 BEING THERE ....................................... -

Mao's Failure, Deng's Success

MAO'S FAILURE, DENG'S SUCCESS Roderick MacFarquhar Professor of History and Political Science, Harvard University June 24, 2010 Revolutionaries have to be optimists as well as believers, and revolutionary leaders have to be able to inspire their followers, convince them that "Yes, we can!" How could they endure years of struggle on a long march towards a seemingly ever-receding promised land without believing, as Mao Zedong put it during the darkest days of the Chinese revolution, that "a single spark can start a prairie fire?" During the anti-Japanese war, Mao laid down that in the aftermath of defeat, a communist should correct his ideas "to make them correspond to the laws of the external world, and thus turn failure into success; this is what is meant by 'failure is the mother of success' and 'a fall into the pit, a gain in your wit."1 Twenty years later, during the upheaval within international communism brought about by Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalin and the subsequent Hungarian revolt, Mao remained determinedly optimistic, claiming that bad things can be turned into good things ... In given conditions, a bad thing can lead to good results and a good thing to bad results. More than two thousand years ago Lao Tzu said: "Good fortune lieth within bad, bad fortune lurketh within good."2 Alas for Mao, not only was Lao Tzu right, but, more importantly, Mao's countrymen and his successors did not agree with him as to what constituted good and bad things. On his deathbed, Mao claimed that the Cultural Revolution was one of his two major lifetime achievements, the other being the victory that brought the communists to power in 1949.3 But within the utopian vision of Mao's Cultural Revolution, egalitarian and collectivist though it was, lurked the seeds of its antithesis, the Chairman's bête noire, the helter- skelter capitalism of the Deng Xiaoping era. -

The CCP Central Committee's Leading Small Groups Alice Miller

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 26 The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups Alice Miller For several decades, the Chinese leadership has used informal bodies called “leading small groups” to advise the Party Politburo on policy and to coordinate implementation of policy decisions made by the Politburo and supervised by the Secretariat. Because these groups deal with sensitive leadership processes, PRC media refer to them very rarely, and almost never publicize lists of their members on a current basis. Even the limited accessible view of these groups and their evolution, however, offers insight into the structure of power and working relationships of the top Party leadership under Hu Jintao. A listing of the Central Committee “leading groups” (lingdao xiaozu 领导小组), or just “small groups” (xiaozu 小组), that are directly subordinate to the Party Secretariat and report to the Politburo and its Standing Committee and their members is appended to this article. First created in 1958, these groups are never incorporated into publicly available charts or explanations of Party institutions on a current basis. PRC media occasionally refer to them in the course of reporting on leadership policy processes, and they sometimes mention a leader’s membership in one of them. The only instance in the entire post-Mao era in which PRC media listed the current members of any of these groups was on 2003, when the PRC-controlled Hong Kong newspaper Wen Wei Po publicized a membership list of the Central Committee Taiwan Work Leading Small Group. (Wen Wei Po, 26 December 2003) This has meant that even basic insight into these groups’ current roles and their membership requires painstaking compilation of the occasional references to them in PRC media.