Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

April 28, 1969 Mao Zedong's Speech At

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified April 28, 1969 Mao Zedong’s Speech at the First Plenary Session of the CCP’s Ninth Central Committee Citation: “Mao Zedong’s Speech at the First Plenary Session of the CCP’s Ninth Central Committee,” April 28, 1969, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao, vol. 13, pp. 35-41. Translated for CWIHP by Chen Jian. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/117145 Summary: Mao speaks about the importance of a united socialist China, remaining strong amongst international powers. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation What I am going to say is what I have said before, which you all know, and I am not going to say anything new. Simply I am going to talk about unity. The purpose of unity is to pursue even greater victory. Now the Soviet revisionists attack us. Some broadcast reports by Tass, the materials prepared by Wang Ming,[i] and the lengthy essay in Kommunist all attack us, claiming that our Party is no longer one of the proletariat and calling it a “petit-bourgeois party.” They claim that what we are doing is the imposition of a monolithic order and that we have returned to the old years of the base areas. What they mean is that we have retrogressed. What is a monolithic order? According to them, it is a military-bureaucratic system. Using a Japanese term, this is a “system.” In the words used by the Soviets, this is called “military-bureaucratic dictatorship.” They look at our list of names, and find many military men, and they call it “military.”[ii] As for “bureaucratic,” probably they mean a batch of “bureaucrats,” including myself, [Zhou] Enlai, Kang Sheng, and Chen Boda.[iii] All in all, those of you who do not belong to the military belong to this “bureaucratic” system. -

January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu Citation: “Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu,” January 14, 1950, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi, ed., Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao (Mao Zedong’s Manuscripts since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China), vol. 1 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1987), 237; translation from Shuguang Zhang and Jian Chen, eds.,Chinese Communist Foreign Policy and the Cold War in Asia: New Documentary Evidence, 1944-1950 (Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1996), 137. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112672 Summary: Mao Zedong gives instructions to Hu Qiaomu on how to write about recent developments within the Japanese Communist Party. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document [...] Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu: I shall leave for Leningrad today at 9:00 p.m. and will not be back for three days. I have not yet received the draft of the Renmin ribao ["People's Daily"] editorial and the resolution of the Japanese Communist Party's Politburo. If you prefer to let me read them, I will not be able to give you my response until the 17th. You may prefer to publish the editorial after Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi has read them. Out party should express its opinion by supporting the Cominform bulletin's criticism of Nosaka and addressing our disappointment over the Japanese Communist Party Politburo's failure to accept the criticism. It is hoped that the Japanese Communist Party will take appropriate steps to correct Nosaka's mistakes. -

Paris Commune Imagery in China's Mass Media

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 128 852 CS 202 971 AUTHOR Meiss, Guy T. TITLE Paris Commune Imagery in China's mass Media. PUB DATE 76 NOT: 38p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism (59th, College Park, Maryland, July 31-August 4, 1976) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Imagery; *Information Dissemination; Journalism; *Mass Media; Persuasive Discourse; Political Influences; *Political Socialization; *Propaganda; Rhetorical Criticism IDENTIFIERS China; Paris Commune; Shanghai Peoples Commune ABSTRACT The role of ideology in mass media practices is explored in an analysis of the relation between theParis Commune of 1871 and the Shanghai Commune of 1967, two attempts totranslate the -philosophical concept of dictatorship of the proletariatinto some political form. A review of the use of Paris Commune imagery bythe Chinese to mobilize the population for politicaldevelopment highlights the critical role of ideology in understanding the operation of the mass media and the difficulties theChinese have in continuing their revolution in the political andbureaucratic superstructure. (Author/AA) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include manyinformal unpublished * materials not available from other sources.ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available.Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encounteredand this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopyreproductions ERIC makes -

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

China's Fear of Contagion

China’s Fear of Contagion China’s Fear of M.E. Sarotte Contagion Tiananmen Square and the Power of the European Example For the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), erasing the memory of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square massacre remains a full-time job. The party aggressively monitors and restricts media and internet commentary about the event. As Sinologist Jean-Philippe Béja has put it, during the last two decades it has not been possible “even so much as to mention the conjoined Chinese characters for 6 and 4” in web searches, so dissident postings refer instead to the imagi- nary date of May 35.1 Party censors make it “inconceivable for scholars to ac- cess Chinese archival sources” on Tiananmen, according to historian Chen Jian, and do not permit schoolchildren to study the topic; 1989 remains a “‘for- bidden zone’ in the press, scholarship, and classroom teaching.”2 The party still detains some of those who took part in the protest and does not allow oth- ers to leave the country.3 And every June 4, the CCP seeks to prevent any form of remembrance with detentions and a show of force by the pervasive Chinese security apparatus. The result, according to expert Perry Link, is that in to- M.E. Sarotte, the author of 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe, is Professor of History and of International Relations at the University of Southern California. The author wishes to thank Harvard University’s Center for European Studies, the Humboldt Foundation, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the University of Southern California for ªnancial and institutional support; Joseph Torigian for invaluable criticism, research assistance, and Chinese translation; Qian Qichen for a conversation on PRC-U.S. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

Mao Zedong in Contemporarychinese Official Discourse Andhistory

China Perspectives 2012/2 | 2012 Mao Today: A Political Icon for an Age of Prosperity Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory Arif Dirlik Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 4 June 2012 Number of pages: 17-27 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Arif Dirlik, « Mao Zedong in ContemporaryChinese Official Discourse andHistory », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/2 | 2012, Online since 30 June 2015, connection on 28 October 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5852 ; DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5852 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Mao Zedong in Contemporary Chinese Official Discourse and History ARIF DIRLIK (1) ABSTRACT: Rather than repudiate Mao’s legacy, the post-revolutionary regime in China has sought to recruit him in support of “reform and opening.” Beginning with Deng Xiaoping after 1978, official (2) historiography has drawn a distinction between Mao the Cultural Revolutionary and Mao the architect of “Chinese Marxism” – a Marxism that integrates theory with the circumstances of Chinese society. The essence of the latter is encapsulated in “Mao Zedong Thought,” which is viewed as an expression not just of Mao the individual but of the collective leadership of the Party. In most recent representations, “Chinese Marxism” is viewed as having developed in two phases: New Democracy, which brought the Communist Party to power in 1949, and “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” inaugurated under Deng Xiaoping and developed under his successors, and which represents a further development of Mao Zedong Thought. -

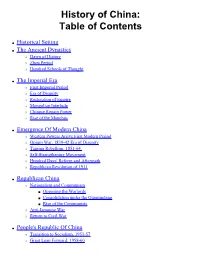

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Talk About a Revolution: Red Guards, Government Cadres, and the Language of Political Discourse

Talk About a Revolution: Red Guards, Government Cadres, and the Language of Political Discourse Schoenhals, Michael 1993 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Schoenhals, M. (1993). Talk About a Revolution: Red Guards, Government Cadres, and the Language of Political Discourse. (Indiana East Asian Working Paper Series on Language and Politics in Modern China). http://www.indiana.edu/~easc/resources/working_paper/noframe_schoenhals_pc.htm Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Talk About a Revolution: Red Guards, Government Cadres, -

China's Lost Decade'

Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade” Gregory B. Lee To cite this version: Gregory B. Lee. Preamble, Introduction and Epilogue to ”China’s Lost Decade”. China’s Lost Decade: Cultural Politics and Poetics 1978-1990 - In Place of History, Tigre de Papier, 391 p., 2009. hal- 00385268 HAL Id: hal-00385268 https://hal-univ-lyon3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00385268 Submitted on 21 May 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHINA©S LOST DECADE CULTURAL POLITICS AND POETICS 1978-1990 IN PLACE OF HISTORY Gregory B. Lee Tigre de Papier In memory of Paola Sandri 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................. 7 PREAMBLE ............................................... 11 THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT ................... 12 INTRODUCTION ........................................ 18 THE BEGINNING OF THE 'LOST DECADE' ............................................................. 19 THE END OF THE DECADE .................... 33 LANGUAGE OF THE DECADE ................ 36 BEING THERE .......................................