Negotiating History: the Chinese Communist Party's 1981

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Climate-Change Journalism in China: Opportunities for International

Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall Foreword by Hu Shuli 中国气候变化报道: 国际合作中的机遇 山姆·吉尔 序——胡舒立 Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation 中国气候变化报道:国际合作中的机遇 © International Media Support 2011. Any reproduction, modification, publication, transmission, transfer, sale distribution, display or exploitation of this information, in any form or by any means, or its storage in a retrieval system, whether in whole or in part, without the express written permission of the individual copyright holder is prohibited without prior approval by IMS. Cover image by Angel Hsu. © 国际媒体支持组织 版权所有 2011 任何媒体、网站或个人未经“国际媒体支持组织”的书面许可,不得引用、复 制、转载、摘编、发售、储存于检索系统,或以其他任何方式非法使用本报告全 部或部分内容。 封面照片由徐安琪摄。 International Media Support (IMS) Communications Unit, Nørregade 18, Copenhagen K 1165, Denmark Phone: +4588327000, Fax: +4533120099 Email: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk Caixin Media Floor 15/16, Tower A, Winterless Center, No.1 Xidawanglu, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, P.R.China http://english.caing.com/ chinadialogue Suite 306 Grayston Centre, 28 Charles Square, London N1 6HT, United Kingdom Phone: +442073244767 Email: [email protected] www.chinadialogue.net Climate-change journalism in China: opportunities for international cooperation By Sam Geall1 Foreword by Hu Shuli2 p4 1. Sam Geall is deputy editor of chinadialogue. The author acknowledges generous contributions to the research and analysis in this report from Li Hujun, Wang Haotong, Eliot Gao and Lisa Lin. Essential input and support were also provided by Martin Breum, Martin Gottske, Isabel Hilton, Tan Copsey, Li Dawei, Ma Ling, Hu Shuli, Bruce Lewenstein and Jia Hepeng. 2. Hu Shuli is editor-in-chief of Caixin Media (the Beijing-based media group that publishes Century Weekly and China Reform), the former founding editor of Caijing magazine and a prominent investigative journalist and commentator. -

January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified January 14, 1950 Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu Citation: “Telegram, Mao Zedong to Hu Qiaomu,” January 14, 1950, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Zhonggong zhongyang wenxian yanjiushi, ed., Jianguo yilai Mao Zedong wengao (Mao Zedong’s Manuscripts since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China), vol. 1 (Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe, 1987), 237; translation from Shuguang Zhang and Jian Chen, eds.,Chinese Communist Foreign Policy and the Cold War in Asia: New Documentary Evidence, 1944-1950 (Chicago: Imprint Publications, 1996), 137. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/112672 Summary: Mao Zedong gives instructions to Hu Qiaomu on how to write about recent developments within the Japanese Communist Party. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document [...] Comrade [Hu] Qiaomu: I shall leave for Leningrad today at 9:00 p.m. and will not be back for three days. I have not yet received the draft of the Renmin ribao ["People's Daily"] editorial and the resolution of the Japanese Communist Party's Politburo. If you prefer to let me read them, I will not be able to give you my response until the 17th. You may prefer to publish the editorial after Comrade [Liu] Shaoqi has read them. Out party should express its opinion by supporting the Cominform bulletin's criticism of Nosaka and addressing our disappointment over the Japanese Communist Party Politburo's failure to accept the criticism. It is hoped that the Japanese Communist Party will take appropriate steps to correct Nosaka's mistakes. -

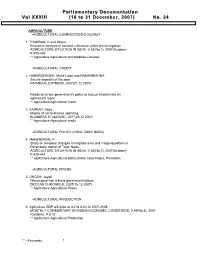

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

The Comintern in China

The Comintern in China Chair: Taylor Gosk Co-Chair: Vinayak Grover Crisis Director: Hannah Olmstead Co-Crisis Director: Payton Tysinger University of North Carolina Model United Nations Conference November 2 - 4, 2018 University of North Carolina 2 Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director 3 Introduction 5 Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang 7 The Mission of the Comintern 10 Relations between the Soviets and the Kuomintang 11 Positions 16 3 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to UNCMUNC X! My name is Hannah Olmstead, and I am a sophomore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am double majoring in Public Policy and Economics, with a minor in Arabic Studies. I was born in the United States but was raised in China, where I graduated from high school in Chengdu. In addition to being a student, I am the Director-General of UNC’s high school Model UN conference, MUNCH. I also work as a Resident Advisor at UNC and am involved in Refugee Community Partnership here in Chapel Hill. Since I’ll be in the Crisis room with my good friend and co-director Payton Tysinger, you’ll be interacting primarily with Chair Taylor Gosk and co-chair Vinayak Grover. Taylor is a sophomore as well, and she is majoring in Public Policy and Environmental Studies. I have her to thank for teaching me that Starbucks will, in fact, fill up my thermos with their delightfully bitter coffee. When she’s not saving the environment one plastic cup at a time, you can find her working as the Secretary General of MUNCH or refereeing a whole range of athletic events here at UNC. -

China's Foreign Policy Dilemma

February 2013 ANALYSIS LINDA JAKOBSON China’s Foreign Policy Program Director East Asia Dilemma Tel: +61 2 8238 9070 [email protected] E xecutive summary Foreign policy will not be a top priority of China’s new leader Xi Jinping. Xi is under pressure from many sectors of society to tackle China’s formidable domestic problems. To stay in power Xi must ensure continued economic growth and social stability. Due to the new leadership’s preoccupation with domestic issues, Chinese foreign policy can be expected to be reactive. This may have serious consequences because of the potentially explosive nature of two of China’s most pressing foreign policy challenges: how to decrease tensions with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands and with Southeast Asian states over territorial claims in the South China Sea. A lack of attention by China’s senior leaders to these sovereignty disputes is a recipe for disaster. If a maritime or aerial incident occurs, nationalist pressure will narrow the room for manoeuvre of leaders in each of the countries involved in the incident. There are numerous foreign and security policy actors within China who favour Beijing taking a more forceful stance in its foreign policy. Regional stability could be at risk if China’s new leadership merely reacts as events unfold, as has too often been the case in recent years. LOWY INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL POLICY 31 Bligh Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 8238 9000 Fax: +61 2 8238 9005 www.lowyinstitute.org The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent policy think tank. -

Yundong: Mass Movements in Chinese Communist Leadership a Publication of the Center for Chinese Studies University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

Yundong: Mass Movements in Chinese Communist Leadership A publication of the Center for Chinese Studies University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 Cover Colophon by Shih-hsiang Chen Although the Center for Chinese Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of monographs in this series, respon sibility for the opinions expressed in them and for the accuracy of statements contained in them rests with their authors. @1976 by the Regents of the University of California ISBN 0-912966-15-7 Library of Congress Catalog Number 75-620060 Printed in the United States of America $4.50 Center for Chinese Studies • CHINA RESEARCH MONOGRAPHS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY NUMBER TWELVE YUNDONG: MASS CAMPAIGNS IN CHINESE COMMUNIST LEADERSHIP GORDON BENNETT 4 Contents List of Abbreviations 8 Foreword 9 Preface 11 Piny in Romanization of Familiar Names 14 INTRODUCTION 15 I. ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT 19 Background Factors 19 Immediate Factors 28 Development after 1949 32 II. HOW TO RUN A MOVEMENT: THE GENERAL PATTERN 38 Organizing a Campaign 39 Running a Compaign in a Single Unit 41 Summing Up 44 III. YUNDONG IN ACTION: A TYPOLOGY 46 Implementing Existing Policy 47 Emulating Advanced Experience 49 Introducing and Popularizing a New Policy 55 Correcting Deviations from Important Public Norms 58 Rectifying Leadership Malpractices among Responsible Cadres and Organizations 60 Purging from Office Individuals Whose Political Opposition Is Excessive 63 Effecting Enduring Changes in Individual Attitudes and Social Institutions that Will Contribute to the Growth of a Collective Spirit and Support the Construction of Socialism 66 IV. DEBATES OVER THE CONTINUING VALUE OF YUNDONG 75 Rebutting the Critics: Arguments in Support of Campaign Leadership 80 V. -

Heretics of China. the Psychology of Mao and Deng

HERETICS OF CHINA HERETICS OF CHINA THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MAO AND DENG NABIL ALSABAH URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-445061 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20378/irbo-44506 Copyright © 2019 by Nabil Alsabah Cover design by Katrin Krause Cover illustration by Daiquiri/Shutterstock.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. ISBN: 978-1-69157-995-2 Created with Vellum During his years in power, Mao Zedong initiated three policies which could be described as radical departures from Soviet and Chinese Communist practice: the Hundred Flowers of 1956-1957, the Great Leap Forward 1958-1960, and the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976. Each was a disaster: the first for the intellectuals, the second for the people, the third for the Party, all three for the country. — RODERICK MACFARQUHAR, THE SECRET SPEECHES OF CHAIRMAN MAO In many ways, [Deng Xiaoping’s] reputation is underestimated: while Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev oversaw the peaceful end of Soviet communist rule and the dismembering of the Soviet empire, he had wanted to keep the Soviet Union in place and reform it. Instead it fell apart; communism lost power—and Russia endured a decade of instability […]. Perhaps the most influential political titan of the late 20th century, Deng succeeded in guiding China towards his vision where his fellow communist leaders failed. — SIMON SEBAG MONTEFIORE, TITANS OF HISTORY CONTENTS Introduction ix 1. -

Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers"

Vol. 26, No. 33 August 15, 1983 EIJIN A CHINESE WEEKLY OF EW NEWS AND VIEWS Deng Xiaoping on "Two Whatevers" Military Leader's Works Published Beijing Plans Urban Development Interestingly, when many mem- don't mean that there isn't room bers read the article which I for improvement. LETTERS brought to one of our sessions, a Alejandreo Torrejon M. desire was expressed to explore Sucre, Bolivia Retirement the possibility of visiting China for the very purpose of sharing Once again, I write to commend our ideas with people in China. Documents you for a most interesting and, to We are in the midst of doing just People like us who follow the me, a most meaningful article that. Thus, your magazine has developments in China only by dealing with retirees ("When borne some unexpected fruit. reading your articles cannot know Leaders or Professionals Retire," if the Sixth Five-Year Plan issue No. 19). It is a credit to Louis P. Schwartz ("Documents," issue No. 21) is ap- your social approach that yQu are New York, USA plicable just by glancing over it. examining the role of profes- However, it is still a good article sionals, administrators and gov- with reference value for people ernmental leaders with an eye to Chinese-Type Modernization who want to observe and follow what they can expect when they China's developments. I plan to leave the ranks of direct workin~ The series of articles on Chi- read it over again carefully and people and enter the ranks of "re- nese-Type Modernization and deepen my understanding. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

Reflections on 40 Years of China's Reforms

Reflections on Forty Years of China’s Reforms Speech at the Fudan University’s Fanhai School of International Finance January 2018 Bert Hofman, World Bank1 This conference is the first of undoubtedly many that will commemorate China’s 40 years of reform and opening up. In December 2018, it will have been 40 years since Deng Xiaoping kicked off China’s reforms with his famous speech “Emancipate the mind, seeking truth from fact, and unite as one to face the future,” which concluded that year’s Central Economic Work Conference and set the stage for the 3rd Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. The speech brilliantly used Mao Zedong’s own thoughts to depart from Maoism, rejected the “Two Whatevers” of Mao’s successor Hua Guofeng (“Whatever Mao said, whatever Mao did”), and triggered decades of reforms that would bring China where it is now—the second largest economy in the world, and one of the few countries in the world that will soon2 have made the journey from low income country to high income country. This 40th anniversary is a good time to reflect on China’s reforms. Understanding China’s reforms is of importance first and foremost for getting the historical record right, and this record is still shifting despite many volumes that have already been devoted to the topic. Understanding China’s past reforms and with it the basis for China’s success is also important for China’s future reforms—understanding the path traveled, the circumstances under which historical decisions were made and what their effects were on the course of China’s economy will inform decision makers on where to go next. -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development.