Harmonious Society” Rise of the New China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

Proquest Dissertations

The diffusion of the Internet in China Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Foster, William Abbott Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 12:10:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289812 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality Illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2003: China (Includes Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau)

Page 1 of 66 China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau) Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 (Note: Also see the section for Tibet, the report for Hong Kong, and the report for Macau.) The People's Republic of China (PRC) is an authoritarian state in which, as directed by the Constitution, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP or Party) is the paramount source of power. Party members hold almost all top government, police, and military positions. Ultimate authority rests with the 24-member political bureau (Politburo) of the CCP and its 9-member standing committee. Leaders made a top priority of maintaining stability and social order and were committed to perpetuating the rule of the CCP and its hierarchy. Citizens lacked both the freedom peacefully to express opposition to the Party-led political system and the right to change their national leaders or form of government. Socialism continued to provide the theoretical underpinning of national politics, but Marxist economic planning has given way to pragmatism, and economic decentralization increased the authority of local officials. The Party's authority rested primarily on the Government's ability to maintain social stability; appeals to nationalism and patriotism; Party control of personnel, media, and the security apparatus; and continued improvement in the living standards of most of the country's 1.3 billion citizens. The Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, in practice, the Government and the CCP, at both the central and local levels, frequently interfered in the judicial process and directed verdicts in many high-profile cases. -

5 China Dreaming

5 China Dreaming Representing the Perfect Present, Anticipating the Rosy Future Stefan Landsberger Abstract As China has developed into a relatively well-offf, increasingly urbanized nation, educating the people has become more urgent than ever. Rais- ing (human) quality (素质) has become a major concern for educators and intellectuals who see moral education as a major task of the state. The visual exhortations in public spaces aimed at moral education are dominated by dreaming about a nation that has risen and needs to be taken seriously. The visualization of these dreams resembles commercial advertising, mixing elements like the Great Wall or the Tiananmen Gate building with modern or futuristic images. This chapter focuses on posters, looking at the changes in contents and representation of government visuals in an increasingly urbanized and media-literate society. Keywords: visual propaganda; governmentality; normative propaganda; Chinese Dream; Beijing Olympics 2008 Sometimes one still encounters hand-painted faded slogans in the coun- tryside urging those working in agriculture to learn from Dazhai, or to energetically study Mao Zedong Thought. By and large, political messages and the images they use have disappeared from Chinese public spaces, in particular in urban areas. Yet, the production of these images, of what we would call propaganda, has not stopped; the government remains com- mitted to educating the people, as it has over the millennia. Compared to the fijirst three decades of the People’s Republic, the messages have shifted to moral and normative topics, and their visualization has become much more sophisticated than in the earlier periods. This is partly because they Valjakka, Minna & Wang, Meiqin (eds.), Visual Arts, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China: Urbanized Interface. -

Socioterritorial Fractures in China: the Unachievable “Harmonious Society”?

China Perspectives 2007/3 | 2007 Creating a Harmonious Society Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? Guillaume Giroir Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 DOI : 10.4000/chinaperspectives.2073 ISSN : 1996-4617 Éditeur Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Édition imprimée Date de publication : 15 septembre 2007 ISSN : 2070-3449 Référence électronique Guillaume Giroir, « Socioterritorial Fractures in China: The Unachievable “Harmonious Society”? », China Perspectives [En ligne], 2007/3 | 2007, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2010, consulté le 28 octobre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/2073 ; DOI : 10.4000/ chinaperspectives.2073 © All rights reserved Special feature s e Socioterritorial Fractures v i a t c n i in China: The Unachievable e h p s c “Harmonious Society”? r e p GUILLAUME GIROIR This article offers an inventory of the social and territorial fractures in Hu Jintao’s China. It shows the unarguable but ambiguous emergence of a middle class, the successes and failures in the battle against poverty and the spectacular enrichment of a wealthy few. It asks whether the Confucian ideal of a “harmonious society,” which the authorities have been promoting since the early 2000s, is compatible with a market economy. With an eye to the future, it outlines two possible scenarios on how socioterritorial fractures in China may evolve. he need for a “more harmonious society” was raised 1978, Chinese society has effectively ceased to be founded for the first time in 2002 at the Sixteenth Congress on egalitarianism; spatial disparities are to be seen on the T of the Communist Party of China (CPC). -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development. -

HU Jintao Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 B

◀ HU Die Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. HU Jintao Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 b. 1942 President of China (2002– present) Hu Jintao is the current President of the Peo- of Guizhou Province (July 1985–November 1988), and the ple’s Republic of China. During his two terms party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region (De- in office he has faced several crises, with vary- cember 1988–January 1991). Currently Hu serves as presi- ing degrees of success. His handling of the dent of the PRC, as well as general secretary of CCP’s Central Committee, and chairman of the CCP’s Military 2008 Sichuan earthquake was initially praised Affairs Committee. for his break from previous government se- Since his succession to Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao has crecy but later criticized outside China after taken an active role in developing China’s foreign rela- widespread media censorship of the event be- tions. The first developments were the introduction of came apparent. He has been very active in pro- the concepts “harmonious society” and “peaceful rise,” moting development at home and improving the latter of which was proposed in 2003 by Chairman foreign relations, notably with Taiwan. of the China Reform Forum Zheng Bijian. Peaceful rise, later termed the peaceful development path by Hu, was touted as a path of economic development that could raise “China’s population out of a state of underdevelopment” orn in Shanghai in December 1942, with ances- (Glaser & Medeiros 2007, 295) while working coopera- tral roots in Anhui Province, Hu Jintao gradu- tively with other countries to promote national security ated in 1965 from China’s Qinghua University, and world peace. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

Democratic Centralism and Administration in China

This is the accepted version of the chapter published in: F Hualing, J Gillespie, P Nicholson and W Partlett (eds), Socialist Law in Socialist East Asia, Cambridge University Press (2018) Democratic Centralism and Administration in China Sarah BiddulphP0F 1 1. INTRODUCTION The decision issued by the fourth plenary session of the 18th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP, or Party) in 2014 on Some Major Questions in Comprehensively Promoting Governing the Country According to Law (the ‘Fourth Plenum Decision’) reiterated the Party’s determination to build a ‘socialist rule of law system with Chinese characteristics’.P1F 2P What does this proclamation of the ‘socialist’ nature of China’s version of rule of law mean, if anything? Development of a notion of socialist rule of law in China has included many apparently competing and often mutually inconsistent narratives and trends. So, in searching for indicia of socialism in China’s legal system it is necessary at the outset to acknowledge that what we identify as socialist may be overlaid with other important influences, including at least China’s long history of centralised, bureaucratic governance, Maoist forms of ‘adaptive’ governanceP2F 3P and Western ideological, legal and institutional imports, outside of Marxism–Leninism. In fact, what the Chinese party-state labels ‘socialist’ has already departed from the original ideals of European socialists. This chapter does not engage in a critique of whether Chinese versions of socialism are really ‘socialist’. Instead it examines the influence on China’s legal system of democratic centralism, often attributed to Lenin, but more significantly for this book project firmly embraced by the party-state as a core element of ‘Chinese socialism’. -

Edited LOEBS Cites Plus List of Elements 1 30

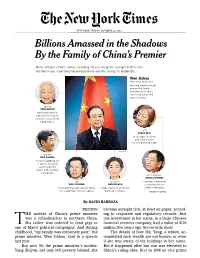

C MCYMK Y K Nxxx,2012-10-26,A,001,Bs-BK,E3Nxxx,2012-10-26,A,001,Bs-BK,E3 C M Y K Nxxx,2012-10-26,A,001,Bs-BK,E3 Late EditionLate Edition C M Y K Nxxx,2012-10-26,A,001,Bs-BK,E3 Today, morning fog and clouds, par- Today, morning fog and clouds, par- tial clearing,Late high 68. Edition Tonight, most- tial clearing, high 68. Tonight, most- ly cloudy,Today, morning mild, low fog 56.and Tomorrow, clouds, par- ly cloudy, mild, low 56. Tomorrow, periodictial clearing, clouds high and 68. sunshine, Tonight, most-high Late Edition periodic clouds and sunshine, high 66. lyWeather cloudy, mild,map lowis on 56. PageTomorrow, Today,B12.morning fog and clouds, par- 66. Weather map is ontial clearing,Page high B12. 68. Tonight, most- periodic clouds and sunshine,ly high cloudy, mild, low 56. Tomorrow, 66. Weather map is on Pageperiodic B12. clouds and sunshine, high 66. Weather map is on Page B12. VOL. CLXII . No. 55,936 © 2012 The New York Times NEW YORK, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2012 $2.50 VOL. CLXII . No. 55,936 © 2012 The New York Times NEW YORK, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2012 $2.50 VOL. CLXII . No. 55,936 © 2012 The New York Times NEW YORK, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2012 $2.50 VOL. CLXII . No. 55,936 © 2012 The New York Times NEW YORK, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2012 $2.50 POLITICAL MEMO POLITICALPOLITICAL MEMO MEMO 2 CHILDREN SLAIN Billions Amassed in the Shadows POLITICAL MEMO 2 CHILDREN2 CHILDREN SLAINObama SLAINBillions Campaign Endgame: Amassed in the Shadows 2 CHILDREN SLAIN Billions Amassed AmassedAT HOME IN CITY; in inBy the thethe ShadowsFamily Shadows of China’s Premier ObamaObama Campaign Campaign Endgame: Endgame: Grunt Work and Cold Math NANNY ARRESTED Obama Campaign Endgame:AT HOMEAT HOME IN CITY; IN CITY; Many relatives of Wen Jiabao, including his son, daughter, younger brother and AT HOME IN CITY; By JIMBy RUTENBERG the Family of brother-in-law,China’s have become extraordinarily Premier wealthy during his leadership.