Seeking Truth from Facts’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Privatization: Between Plan and Market

CHINESE PRIVATIZATION: BETWEEN PLAN AND MARKET LAN CAO* I INTRODUCTION Since 1978, when China adopted its open-door policy and allowed its economy to be exposed to the international market, it has adhered to what Deng Xiaoping called "socialism with Chinese characteristics."1 As a result, it has produced an economy with one of the most rapid growth rates in the world by steadfastly embarking on a developmental strategy of gradual, market-oriented measures while simultaneously remaining nominally socialistic. As I discuss in this article, this strategy of reformthe mere adoption of a market economy while retaining a socialist ownership baseshould similarly be characterized as "privatization with Chinese characteristics,"2 even though it departs markedly from the more orthodox strategy most commonly associated with the term "privatization," at least as that term has been conventionally understood in the context of emerging market or transitional economies. The Russian experience of privatization, for example, represents the more dominant and more favored approach to privatizationcertainly from the point of view of the West and its advisersand is characterized by immediate privatization of the state sector, including the swift and unequivocal transfer of assets from the publicly owned state enterprises to private hands. On the other hand, "privatization with Chinese characteristics" emphasizes not the immediate privatization of the state sector but rather the retention of the state sector with the Copyright © 2001 by Lan Cao This article is also available at http://www.law.duke.edu/journals/63LCPCao. * Professor of Law, College of William and Mary Marshall-Wythe School of Law. At the time the article was written, the author was Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School. -

"Functional Socialism'' and "Functional Capitalism" : the "Socialist Market Economy" in China

"Functional Socialism'' and "Functional Capitalism" : The "Socialist Market Economy" in China 著者 Takeshita Koshi journal or Kansai University review of economics publication title volume 18 page range 1-25 year 2016-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10112/00017203 Kansai University Review of Economics No.18 (March 2016), pp.1-25 ^Tunctional Socialism'' and ^Tunctional Capitalism — The "Socialist Market Economy" in China — Koshi Takeshita Based on a framework that conceives of ownership (property rights) as "a bundle of rights," We propose four types of ownership system, build concept models of "functional socialism" and "func tional capitalism," and then try to clarify the reality of Chinas "socialist market economy" We reached the following conclusions. First, we schematize the correspondence between "functional socialism" and "functional capi talism." Second, we show that a process of land ownership reform and state-owned enterprises reform corresponded with a schema of "functional capitalism." Third, we found that the ownership structure of the "socialist market economy" in China is now sepa rated into three different sets of rights regarding ownership (prop erty rights). Finally, we show that the reality of the "socialist market economy" is not a free market, but a market controlled by the Communist Party. Keywords: market socialism, state capitalism, property rights approach, land owner ship reform, reform of SOEs (state-owned enterprises) 1. Introduction: analytical viewpoint^^ Following the remarkable rise of Chinas economy, there has been an increase in discussion about the diverse forms that capitalism can take.^^However, when one considers that China calls its own system a "socialist market economy," one may wonder if it is better to think about the multiple forms that socialism can take. -

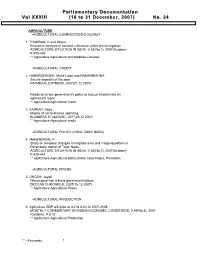

Parliamentary Documentation

PPPaaarrrllliiiaaammmeeennntttaaarrryyy DDDooocccuuummmeeennntttaaatttiiiooonnn VVVooolll XXXXXXXXXIIIIIIIII (((111666 tttooo 333111 DDDeeeccceeemmmbbbeeerrr,,, 222000000777))) NNNooo... 222444 AGRICULTURE -AGRICULTURAL COMMODITIES-COCONUT 1 THAMBAN, C and others Economic analysis of coconut cultivation under micro-irrigation. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.425-430 ** Agriculture-Agricultural commodities-Coconut. -AGRICULTURAL CREDIT 2 HABERBERGER, Marie Luise and RAMAKRISHNA Secure deposits of the poor. FINANCIAL EXPRESS, 2007(21.12.2007) Needs to review government's policy to reduce interest rate on agricultural loans. ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. 3 SARKAR, Keya Modes of micro-finance spending. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(26.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural credit. -AGRICULTURAL POLICY-(INDIA-TAMIL NADU) 4 MAHENDRAN, R Study on temporal changes in Irrigated area and cropping pattern in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. AGRICULTURE SITUATION IN INDIA, V.63(No.7), 2007(October): P.439-444 ** Agriculture-Agricultural policy-(India-Tamil Nadu); Plantation. -AGRICULTURAL PRICES 5 GHOSH, Jayati Wheat price rise reflects government failure. DECCAN CHRONICLE, 2007(18.12.2007) ** Agriculture-Agricultural Prices. -AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 6 Agriculture GDP will grow at 3.2 to 3.6% in 2007-2008. MONTHLY COMMENTARY ON INDIAN ECONOMIC CONDITIONS, V.49(No.3), 2007 (October): P.8-12 ** Agriculture-Agricultural Production. ** - Keywords 1 -AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH 7 NIGADE, R.D Research and developments in small millets in Maharashtra. INDIAN FARMING, V.59(No.5), 2007(August): P.9-10 ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Crops. 8 SUD, Surinder Great new aroma. BUSINESS STANDARD, 2007(18.12.2007) Focuses on research done in Indian Agriculture Research Institute(IARI) for producing latest rice variety. ** Agriculture-Agricultural research; Rice. -AGRICULTURAL TRADE 9 MISHRA, P.K Agricultural market reforms for the benefit of Farmers. -

1How Do We Compare Economies?

1 How Do We Compare Economies? As mankind approaches the end of the millennium, the twin crises of authoritarianism and socialist central planning have left only one competitor standing in the ring as an ideology of potentially uni- versal validity: liberal democracy, the doctrine of individual freedom and popular sovereignty. In its economic manifestation, liberalism is the recognition of the right of free economic activity and economic exchange based on private property and markets. —Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, 1992 INTRODUCTION We have witnessed a profound transformation of the world political and economic order since 1989, the ultimate outcome of which is difficult to foresee. The former Soviet Union (FSU)1 broke up, its empire of satellite states dissolved, and most of the former constituent parts are trying to fulfill Fukyama’s prophecy quoted above. In his view, the end of the Cold War means the convergence of the entire world on the American model of political econ- omy and the end of any significant competition between alternative forms of political or economic systems. Has this prophecy come true? We think not. Certainly during the second half of the 1990s, the economic boom in the United States pushed it forward as a role model that many coun- tries sought and still seek to emulate. But with the outbreak of financial crises in many parts of the globe and the bursting of the American stock market bubble in March 2000, its eco- nomic problems such as continuing poverty and inequality loom large. Furthermore, it is now clear that the problems in the FSU are deeply rooted, with the transitions in various former Soviet republics stalled. -

Socialist Planning

Socialist Planning Socialist planning played an enormous role in the economic and political history of the twentieth century. Beginning in the USSR it spread round the world. It influenced economic institutions and economic policy in countries as varied as Bulgaria, USA, China, Japan, India, Poland and France. How did it work? What were its weaknesses and strengths? What is its legacy for the twenty-first century? Now in its third edition, this textbook is fully updated to cover the findings of the period since the collapse of the USSR. It provides an overview of socialist planning, explains the underlying theory and its limitations, looks at its implementation in various sectors of the economy, and places developments in their historical context. A new chap- ter analyses how planning worked in the defence–industry complex. This book is an ideal text for undergraduate and graduate students taking courses in comparative economic systems and twentieth-century economic history. michael ellman is Emeritus Professor in the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. He is the author, co- author and editor of numerous books and articles on the Soviet and Russian economies, on transition economics, and on Soviet economic and political history. In 1998, he was awarded the Kondratieff prize for his ‘contributions to the development of the social sciences’. Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 128.122.253.212 on Sat Jan 10 18:08:28 GMT 2015. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139871341 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2015 Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 128.122.253.212 on Sat Jan 10 18:08:28 GMT 2015. -

How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 Pp

44795_Book_Reviews:19016_Cato 8/29/13 11:56 AM Page 613 Book Reviews Readers searching for such hypothetical society-building will go away disappointed—and that, finally, is what Two Cheers is about. Such projects end in disappointment. That’s exactly what they always do. Jason Kuznicki Cato Institute How China Became Capitalist Ronald Coase and Ning Wang Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 256 pp. In 1981, shortly after China began to liberalize its economy, Steven N. S. Cheung predicted that free markets would trump state planning and eventually China would “go ‘capitalist’.” He grounded his analysis in property rights theory and the new institutional eco- nomics, of which he was a pioneer. Ronald Coase, a longtime profes- sor of law and economics at the University of Chicago and Cheung’s colleague during 1967–69, agreed with that prediction. Now the Nobel laureate economist has teamed up with Ning Wang, a former student and a senior fellow at the Ronald Coase Institute, to provide a detailed account of “how China became capitalist.” The hallmark of this book is the use of primary sources to provide an in-depth view of the institutional changes that took place during the early stages of China’s economic reforms and the use of Coaseian analysis to understand those changes. In particular, Coase’s distinc- tion between the market for goods and the market for ideas is applied to China’s reform movement and gives a fresh perspective of how China was able to make the transition from plan to market. The key conclusion is that the absence of a free market for ideas is a threat to China’s future development. -

Mao on Investigation and Research

Intra-party document Zhongfa [1961] No. 261 Do not lose [A complete translation into English of] Mao Zedong on Investigation and Research Central Committee General Office Confidential Office print. 4 April 1961 (CCP Hebei Provincial Committee General Office reprint.) 15 April 1961 Notification This collection of texts is an intra-Party document distributed to the county level in the civilian local sector, to the regiment level in the armed forces, and to the corresponding level in other sectors. It is meant to be read by cadres at or above the county/regiment level. For convenience’s sake, we only print and forward sample copies. We expect the total number of copies needed by the cadres at the designated levels to be printed up and distributed by the Party committees of the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, by the [PLA] General Political Department, by the Party committee of the organs immediately subordinate to the [Party] Centre, and by the Party committee of the central state organs. Please do not reproduce this collection in Party journals. Central Committee General Office 4 April 1961 2 Contents Page On Investigation Work (Spring of 1930) 5 Appendix: Letter from the CCP Centre to the Centre’s Regional Bureaus and the Party Committees of the Provinces, Municipalities, and [Autonomous] Regions Concerning the Matter of Conscientiously Carrying out Investigations (23 March 1961) 13 Preface to Rural Surveys (17 March 1941) 15 Reform Our Study (May 1941) 18 Appendix: CCP Centre Resolution on Investigation and Research (1 -

Market Socialism As a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production

New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 2012) Pp. 20-50 Market Socialism as a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production Alberto Gabriele UNCTAD Francesco Schettino University of Rome ABSTRACT: This paper argues that, during the present historical period, only one mode of production is sustainable, which we call the modern mode of production. Nevertheless, there can be (both in theory and in practice) enough differences among the specific forms of modern mode of production prevailing in different countries to justify the identification of distinct socioeconomic formations, one of them being market socialism. In its present stage of evolution, market socialism in China and Vietnam allows for a rapid development of productive forces, but it is seriously flawed from other points of view. We argue that the development of a radically reformed and improved form of market social- ism is far from being an inevitable historical necessity, but constitutes a theoretically plausible and auspicable possibility. KEYWORDS: Marx, Marxism, Mode of Production, Socioeconomic Formation, Socialism, Communism, China, Vietnam Introduction o our view, the correct interpretation of the the most advanced mode of production, capitalism, presently existing market socialism system (MS) was still prevailing only in a few countries. Yet, Marx Tin China and Vietnam requires a new and partly confidently predicted that, thanks to its intrinsic modified utilization of one of Marx’s fundamental superiority and to its inbuilt tendency towards inces- categories, that of mode of production. According to sant expansion, capitalism would eventually embrace Marx, different Modes of Production (MPs) and dif- the whole world. -

Socialist Political Economy with Chinese Characteristics in a New

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2516-1652.htm Socialist Socialist political economy with political Chinese characteristics in a economy new era Yinxing Hong 259 Nanjing University, Nanjing, China Received 18 October 2020 Revised 18 October 2020 Abstract Accepted 18 October 2020 Purpose – The socialist political economy with Chinese characteristics reflects the characteristics of ushering into a new era, and the research object thereof shifts to productive forces. Emancipating and developing productive forces and achieving common prosperity become the main theme. Wealth supersedes value as the fundamental category of economic analysis. Design/methodology/approach – The theoretical system of socialist political economy with Chinese characteristics cannot proceed from transcendental theories but is problem-oriented. Leading problems involve development stages and research-level problems. Findings – The economic operation analysis is subject to the goal of optimal allocation of resources with micro-level analysis focused on efficiency and macro-level analysis focused on economic growth and macroeconomic stability also known as economic security. The economic development analysis explores the laws of development and related development concepts in compliance with laws of productive forces. The new development concepts i.e. the innovative coordinated green open and shared development drive the innovation of development theory in political economy. Originality/value – Accordingly, the political economy cannot study the system only, but also needs to study the problems of economic operation and economic development. Therefore, the theoretical system of the political economy tends to encompass three major parts, namely economic system, economic operation and economic development (including foreign economy). -

The Changing Face of Chinese Socialism

The Changing Face Of Chinese Socialism Xe_~v SenJice- In 1979, the United States transitioned from recognizing the Republic of China (Taiwan) to the People's Republic of China as the "official" China. Following the death of Mao Zedong, premier of the People's Republic of China and Chairman of the Chinese Commu- nist Party, in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to a screeching halt. Hua Guofeng became the chairman of the CCP while Deng Xiaop- eng eventually rose to the rank of Vice-premier, although Deng's role would prove more important than his title would suggest. At the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee in 1978, Deng Xiaop- eng laid the groundwork for what would become his political philos- ophy as well as the roots of what would become his economic policy, including modernizing China's economy. This paper will largely use The Beijing (Peking) Review to argue that Deng Xiaoping used for- eign-facing propaganda to sell his policy ideas to the United States and change the face of China. His goal was to abolish the Maoist pol- icy of continuous revolution which had caused such a lack of confi- dence in China; Deng's policy was to move forward to a more predict- able China, one in which foreign investments would be safe. The economic reforms instituted by Deng during the 1980s served primarily to modernize China's economy and transition from purely agrarian-centered economic policy to a hybrid economy that emphasized a balance of all aspects of the economy. However, there was also a foreign policy aspect to Deng's new economic policy. -

The Social Market Economy As a Model for Sustainable Growth in Developing and Emerging Countries

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Wrobel, Ralph M. Article The social market economy as a model for sustainable growth in developing and emerging countries Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES) Provided in Cooperation with: Opole University Suggested Citation: Wrobel, Ralph M. (2012) : The social market economy as a model for sustainable growth in developing and emerging countries, Economic and Environmental Studies (E&ES), ISSN 2081-8319, Opole University, Faculty of Economics, Opole, Vol. 12, Iss. 1, pp. 47-63 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/93193 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu www.ees.uni.opole.pl ISSN paper version 1642-2597 ISSN electronic version 2081-8319 Economic and Environmental Studies Vol. -

No. 850, June 10, 2005

W(JRKERS IIIINfJlJlIRIJ soc No.SSO ®€Q9u~C'701 • 10 June 200S Occupation of Iraq and the "War on Terror" ies, orlure • • an - - moerla Ism In the year since the Abu Ghraib Thomas Friedman argues to close tortures came to light, one expose down Guantanamo because "I want after another has confirmed that the to win the war on terrorism," adding policies of torture and humiliation that the deaths of over 100 detai have come from the top of this gov nees in American custody "is not just ernment. The official use of torture deeply immoraL it is strategically extends well beyond Abu Ghraib dangerous'-' He concludes his col into other prisons in Iraq. Afghani umn by quoting the executive direc ,tan and the notorious concentration tor of Human Rights First: "If we camp in GuanUinamo Bay. Cuba. are going to transform the Middle where some 500 prisoners continue East, we have to be law-abiding and to be held with('c:t charge or trial. uphold the values we want them to The line of the Bush administration embrace-otherwise it is not going to ha~ been to deny every new report work'-' Meanwhile. in its recent report that comes out documenting more on Guantanamo. Amnesty Interna torture and brutality. When Amnesty tionaL too, is concerned that "the rule fnternational released its report last of law. and the:efore, ultimately_ month condemning the U.S. for its security. is heing undcrmincd. a.' j" mass detentions, torture, disappear any moral credibility the USA claims ances and elimination of the right to to have in seeking to advance human trial