Between Problems (Wenti) and -Isms (Zhuyi), a Hundred Years Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

The Comintern in China

The Comintern in China Chair: Taylor Gosk Co-Chair: Vinayak Grover Crisis Director: Hannah Olmstead Co-Crisis Director: Payton Tysinger University of North Carolina Model United Nations Conference November 2 - 4, 2018 University of North Carolina 2 Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director 3 Introduction 5 Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang 7 The Mission of the Comintern 10 Relations between the Soviets and the Kuomintang 11 Positions 16 3 Letter from the Crisis Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to UNCMUNC X! My name is Hannah Olmstead, and I am a sophomore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I am double majoring in Public Policy and Economics, with a minor in Arabic Studies. I was born in the United States but was raised in China, where I graduated from high school in Chengdu. In addition to being a student, I am the Director-General of UNC’s high school Model UN conference, MUNCH. I also work as a Resident Advisor at UNC and am involved in Refugee Community Partnership here in Chapel Hill. Since I’ll be in the Crisis room with my good friend and co-director Payton Tysinger, you’ll be interacting primarily with Chair Taylor Gosk and co-chair Vinayak Grover. Taylor is a sophomore as well, and she is majoring in Public Policy and Environmental Studies. I have her to thank for teaching me that Starbucks will, in fact, fill up my thermos with their delightfully bitter coffee. When she’s not saving the environment one plastic cup at a time, you can find her working as the Secretary General of MUNCH or refereeing a whole range of athletic events here at UNC. -

1 EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor

EDWARD A. MCCORD Professor of History and International Affairs The George Washington University CONTACT INFORMATION Office: 1957 E Street, NW, Suite 503 Sigur Center for Asian Studies The George Washington University Washington, D.C. 20052 Phone: 202-994-5785 Fax: 202-994-6096 Home: 807 Philadelphia Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20910 Phone: 301-588-6948 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Michigan, History, 1985 M.A. University of Michigan, History, 1978 B.A. Summa Cum Laude, Marian College, History, 1973 OVERSEAS STUDY AND RESEARCH 1992-1993 Research, People's Republic of China Summer 1992 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan 1981-1983 Dissertation Research, People's Republic of China 1975-1977 Inter-University Chinese Language Program, Taipei, Taiwan ACADEMIC POSITIONS Professor of History and International Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2015 to present (Associatte Professor of History and International Affairs, September 1994 to July 2015). Director, Taiwan Education and Research Program, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. May 2004 to present. Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University, August 2011 to June 2014. Deputy Chair, History Department, The George Washington University, July 2009 to August 2011. 1 Senior Associate Dean for Management and Planning, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. July 2005 to August 2006. Associate Dean for Faculty and Student Affairs, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. January 2004 to June 2005. Associate Director, Sigur Center for Asian Studies, The George Washington University. July-December 2003. Acting Dean, Elliott School of International Affairs, The George Washington University. -

Hu Shih and Education Reform

Syracuse University SURFACE Theses - ALL June 2020 Moderacy and Modernity: Hu Shih and Education Reform Travis M. Ulrich Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/thesis Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ulrich, Travis M., "Moderacy and Modernity: Hu Shih and Education Reform" (2020). Theses - ALL. 464. https://surface.syr.edu/thesis/464 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This paper focuses on the use of the term “moderate” “moderacy” as a term applied to categorize some Chinese intellectuals and categorize their political positions throughout the 1920’s and 30’s. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the label of “moderate” (温和 or 温和派)became associated with an inability to align with a political or intellectual faction, thus preventing progress for either side or in some cases, advocating against certain forms of progress. Hu Shih, however, who was one of the most influential intellectuals in modern Chinese history, proudly advocated for pragmatic moderation, as suggested by his slogan: “Boldness is suggesting hypotheses coupled with a most solicitous regard for control and verification.” His advocacy of moderation—which for him became closely associated with pragmatism—brought criticism from those on the left and right. This paper seeks to address these analytical assessments of Hu Shih by questioning not just the labeling of Hu Shih as a moderate, but also questioning the negative connotations attached to moderacy as a political and intellectual label itself. -

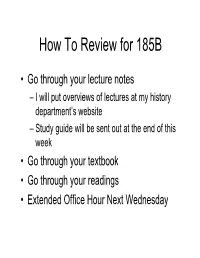

How to Review for 185B

How To Review for 185B • Go through your lecture notes – I will put overviews of lectures at my history department’s website – Study guide will be sent out at the end of this week • Go through your textbook • Go through your readings • Extended Office Hour Next Wednesday Lecture 1 Geography of China • Diverse, continent-sided empire • North vs. South • China’s Rivers RIVERS Yellow 黃河 Yangzi 長江 West 西江/珠江 Beijing 北京 Shanghai 上海 Hong Kong (Xianggang) 香港 Lecture 2 Legacies of the Qing Dynasty 1. The Qing Empire (Multi-ethnic Empire) 2. The 1911 Revolution 3. Imperialisms in China 4. Wordlordism and the Early Republic Qing Dynasty Sun Yat-sen 孙中山 Queue- cutting: 1911 The Abdication of Qing • Yuan Shikai – Negotiation between Yuan (on behalf of the Republican) and the Qing State • Abdication of Qing: Feb 12, 1912 • Yuan became the second provisional president Feb 14, 1912 China’s Last Emperor Xuantong 宣统 (Puyi 溥仪) Threats to China Lecture 3 Early Republic 1. The Yuan Shikai Era: a revisionist history 2. Yuan Shikai’s Rule 3. The Beijing Government 4. Warlords in China Yuan Shikai’s Era The New Republic • The New Election – Guomindang – Progressive Party • The Yuan Shikai Era – Challenges –Problems Beijing Government • Chaotic • Constitutional Warlordism • Militarists? • Cliques under Constitutional Government • The Warlord Era Lecture 4 The New Cultural Movement and the May Fourth 1. China and Chinese Culture in Traditional Time 2. The 1911 Revolution and the Change of Political Culture 3. The New Cultural Movement 4. The May Fourth Movement -

Warlord Era” in Early Republican Chinese History

Mutiny in Hunan: Writing and Rewriting the “Warlord Era” in Early Republican Chinese History By Jonathan Tang A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Wen-hsin Yeh, Chair Professor Peter Zinoman Professor You-tien Hsing Summer 2019 Mutiny in Hunan: Writing and Rewriting the “Warlord Era” in Early Republican Chinese History Copyright 2019 By Jonathan Tang Abstract Mutiny in Hunan: Writing and Rewriting the “Warlord Era” in Early Republican Chinese History By Jonathan Tang Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Wen-hsin Yeh, Chair This dissertation examines a 1920 mutiny in Pingjiang County, Hunan Province, as a way of challenging the dominant narrative of the early republican period of Chinese history, often called the “Warlord Era.” The mutiny precipitated a change of power from Tan Yankai, a classically trained elite of the pre-imperial era, to Zhao Hengti, who had undergone military training in Japan. Conventional histories interpret this transition as Zhao having betrayed his erstwhile superior Tan, epitomizing the rise of warlordism and the disintegration of traditional civilian administration; this dissertation challenges these claims by showing that Tan and Zhao were not enemies in 1920, and that no such betrayal occurred. These same histories also claim that local governance during this period was fundamentally broken, necessitating the revolutionary party-state of the KMT and CCP to centralize power and restore order. Though this was undeniably a period of political turmoil, with endemic low-level armed conflict, this dissertation juxtaposes unpublished material with two of the more influential histories of the era to show how this narrative has been exaggerated to serve political aims. -

Chinese Civil War

asdf Chinese Civil War Chair: Sukrit S. Puri Crisis Director: Jingwen Guo Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Contents Introduction: ……………………………………....……………..……..……3 The Chinese Civil War: ………………………….....……………..……..……6 Background of the Republic of China…………………………………….……………6 A Brief History of the Kuomintang (KMT) ………..……………………….…….……7 A Brief History of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)………...…………...…………8 The Nanjing (Nanking) Decade………….…………………….……………..………..10 Chinese Civil War (1927-37)…………………... ………………...…………….…..….11 Japanese Aggression………..…………….………………...…….……….….................14 The Xi’an Incident..............……………………………..……………………...…........15 Sino-Japanese War and WWII ………………………..……………………...…..........16 August 10, 1945 …………………...….…………………..……………………...…...17 Economic Issues………………………………………….……………………...…...18 Relations with the United States………………………..………………………...…...20 Relations with the USSR………………………..………………………………...…...21 Positions: …………………………….………….....……………..……..……4 2 Chinese Civil War PMUNC 2016 Introduction On October 1, 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong stood atop the Gates of Heavenly Peace, and proclaimed the creation of the People’s Republic of China. Zhongguo -- the cradle of civilization – had finally achieved a modicum of stability after a century of chaotic lawlessness and brutality, marred by foreign intervention, occupation, and two civil wars. But it could have been different. Instead of the communist Chairman Mao ushering in the dictatorship of the people, it could have been the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, of the Nationalist -

Setting the Stage for Constitutional Development: May Fourth and Its Aftermath Yu-Shan Wu

Setting the Stage for Constitutional Development: May Fourth and Its Aftermath Yu-Shan Wu Paper presented at The 61st Annual Conference of the American Association for Chinese Studies, University of Washington, Seattle, October 4-6, 2019 Setting the Stage for Constitutional Development: May Fourth and Its Aftermath China has one of the world’s most ancient civilizations, dating back more than five thousand years. It is easy to emphasize its uniqueness, as Chinese culture, language, political thought, and history appear quite different from those of any of other major countries in the world. Modern Chinese history was punctuated with decisive Western impacts, as that of other countries in the East, but the way China responded to those impacts is often considered to be uniquely Chinese. Furthermore, Chinese political leaders themselves frequently stress that they represent movements that carry uniquely Chinese characteristics. China, it seems, can only be understood in its own light. When put in a global and comparative context, however, China loses many of its unique features. Imperial China, or the Qing dynasty, was an agricultural empire when it met the first serious wave of challenges from the West during the middle of the nineteenth century. The emperor and the mandarins were forced to give up their treasured institutions grudgingly after a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the Westerners. This pattern resembled what occurred in many traditional political systems when confronted with aggression from the West. From that time on, the momentum for political development in China was driven by global competition and the need for national survival. -

Reproductive Subjects: the Global Politics of Health in China, 1927-1964 by Joshua Hubbard a Dissertation Submitted in Partial F

Reproductive Subjects: The Global Politics of Health in China, 1927-1964 by Joshua Hubbard A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History and Women’s Studies) in the University of Michigan 2017 Associate Professor Pär Cassel, Co-Chair Professor Wang Zheng, Co-Chair Professor Susan Greenhalgh, Harvard University Professor Mrinalini Sinha Professor Elizabeth Wingrove Joshua Hubbard [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5850-4314 © Joshua Hubbard 2017 Acknowledgements I am indebted to friends and colleagues who have provided support—in a myriad of ways—along my long and winding path toward completing this dissertation. First and foremost, I want to thank my husband, Joseph Tychonievich, who now knows more about Chinese history than he ever cared to know. He has cooked meals, provided encouragement, helped me think through arguments and questions, and offered feedback on early drafts. Many wonderful people have come into my life since I began my graduate education, but he is chief among them. I am also especially thankful to my sister, Heather Burke, who has been an enduring source of friendship and support for decades. Faculty at Marshall University guided me as I began developing the skills necessary for historical research. I am especially grateful to Fan Shuhua, David Mills, Greta Rensenbrink, Robert Sawrey, Anara Tabyshalieva, Chris White, and Kat Williams. As an East Asian studies master’s student at The Ohio State University, I received excellent mentorship from Joseph Ponce, Christopher Reed, Patricia Sieber, and Ying Zhang. The strong cohort of Chinese studies graduate students there, many of whom have since gone on to become faculty, also pushed me to think deeply and across disciplines. -

The Foundations of Mao Zedong's Political Thought 1917–1935

The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 1917–1935 BRANTLY WOMACK The University Press of Hawaii ● Honolulu Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824879204 (PDF) 9780824879211 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. COPYRIGHT © 1982 BY THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF HAWAII ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Tang and Yi-chuang, and Ann, David, and Sarah Contents Dedication iv Acknowledgments vi Introduction vii 1 Mao before Marxism 1 2 Mao, the Party, and the National Revolution: 1923–1927 32 3 Rural Revolution: 1927–1931 83 4 Governing the Chinese Soviet Republic: 1931–1934 143 5 The Foundations of Mao Zedong’s Political Thought 186 Notes 203 v Acknowledgments The most pleasant task of a scholar is acknowledging the various sine quae non of one’s research. Two in particular stand out. First, the guidance of Tang Tsou, who has been my mentor since I began to study China at the University of Chicago. -

{FREE} Chinese Warlord Armies 1911-30 Ebook Free Download

CHINESE WARLORD ARMIES 1911-30 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip S. Jowett,Stephen Walsh | 48 pages | 21 Sep 2010 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781849084024 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom List of Chinese military equipment in World War II - Wikipedia Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Stephen Walsh Illustrator. Discover the men behind one of the most exotic military environments of the 20th century. Humiliatingly defeated in the Sino-Japanese War and the Boxer Rebellion of , Imperial China collapsed into revolution in the early 20th century and a republic was proclaimed in From the death of the first president in to the rise of the Nationalist Kuomintang go Discover the men behind one of the most exotic military environments of the 20th century. From the death of the first president in to the rise of the Nationalist Kuomintang government in , the differing regions of this vast country were ruled by endlessly forming, breaking and re-forming alliances of regional generals who ruled as 'warlords'. These warlords acted essentially as local kings and, much like Sengoku-period Japan, a few larger power-blocks emerged, fielding armies hundreds of thousands strong. They were also joined by Japanese, White Russian and some Western soldiers of fortune which adds even more color to a fascinating and oft-forgotten period. The fascinating text is illustrated with many rare photographs and detailed uniform plates by Stephen Walsh. Get A Copy. Paperback , 48 pages. More Details Osprey Men at Arms Other Editions 7. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 246 3rd International Conference on Politics, Economics and Law (ICPEL 2018) Intellectuals and State Construction: On Advocates of Good Governmentalism of Hu Shih Scholars during May 4th Period Lei Wang Jiangsu Provincial Research Center for the Theory of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics Nanjing Normal University 210023, Nanjing, China [email protected] Abstract—As midwives of a new era, intellectuals are playing However, though determined Twenty years without politics, Hu a pivotal role in the construction of the modern state at any time. Shih had always been hampered by actual politics, making him Group of scholars as the core of Hu Shih also gave them own eventually "can’t help but" talk about politics.[2] observation and efforts, put forward and practice the mode rn state founding ideas of "Good Governmentalism" in May Fourth Certainly, Hu Shih's "angry to talk about politics" reasons, whether himself or later researchers have given many Period. As an important part of modern Chinese advanced [3] molecular, although advocates of the group of Hu Shih scholars explanations. I believe, The reason why Hu Shih changed his were still some distance away from the reality of China, it original intention of "talking without politics" has his own appeared itself was a kind of exploration of the way out for China, personal factors, but to a large extent, caused by the actual as well as enriched and developed the concept and practice of environment. Warlord repression, political corruption made all state construction in modern China. intellectuals who were deeply edified by practical thoughts can’t but have the responsibility and impulse to interfere in Keywords—May 4th Period; Intellectuals; State Construction; politics.