Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

Vegetable Trade Between Self-Governance and Ethnic Entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gebresenbet, Fana Working Paper Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Gebresenbet, Fana (2018) : Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia, DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1, ISBN 978-87-7605-911-8, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179454 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours the Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia

Relief and Rehabilitation Network Network Paper 4 Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant September 1994 Please send comments on this paper to: Relief and Rehabilitation Network Overseas Development Institute Regent's College Inner Circle Regent's Park London NW1 4NS United Kingdom A copy will be sent to the author. Comments received may be used in future Newsletters. ISSN: 1353-8691 © Overseas Development Institute, London, 1994. Photocopies of all or part of this publication may be made providing that the source is acknowledged. Requests for commercial reproduction of Network material should be directed to ODI as copyright holders. The Network Coordinator would appreciate receiving details of any use of this material in training, research or programme design, implementation or evaluation. Bad Borders Make Bad Neighbours The Political Economy of Relief and Rehabilitation in the Somali Region 5, Eastern Ethiopia Koenraad Van Brabant1 Contents Page Maps 1. Introduction 1 2. Pride and Prejudice in the Somali Region 5 : The Political History of a Conflict 3 * The Ethiopian empire-state and the colonial powers 4 * Greater Somalia, Britain and the growth of Somali nationalism 8 * Conflict and war between Ethiopia and Somalia 10 * Civil war in Somalia 11 * The Transitional Government in Ethiopia and Somali Region 5 13 3. Cycles of Relief and Rehabilitation in Eastern Ethiopia : 1973-93 20 * 1973-85 : `Relief shelters' or the politics of drought and repatriation 21 * 1985-93 : Repatriation as opportunity for rehabilitation and development 22 * The pastoral sector : Recovery or control? 24 * Irrigation schemes : Ownership, management and economic viability 30 * Food aid : Targeting, free food and economic uses of food aid 35 * Community participation and institutional strengthening 42 1 Koenraad Van Brabant has been project manager relief and rehabilitation for eastern Ethiopia with SCF(UK) and is currently Oxfam's country representative in Sri Lanka. -

Somali Region: Multi – Agency Deyr/Karan 2012 Seasonal Assessment Report

SOMALI REGION: MULTI – AGENCY DEYR/KARAN 2012 SEASONAL ASSESSMENT REPORT REGION Somali Regional State November 24 – December 18, 2012 DATE ASSESSMENT STARTED & COMPLETED TEAM MEMBERS – Regional analysis and report NAME AGENCY Ahmed Abdirahman{Ali-eed} SCI Ahmed Mohamed FAO Adawe Warsame UNICEF Teyib Sheriff Nur FAO Mahado Kasim UNICEF Mohamed Mohamud WFP Name of the Agencies Participated Deyr 2012 Need Assessment Government Bureaus DRMFSS, DPPB,RWB,LCRDB,REB,RHB,PCDP UN – WFP,UNICEF,OCHA,FAO,WHO Organization INGO SCI,MC,ADRA,IRC,CHF,OXFAMGB,Intermon Oxfam, IR,SOS,MSFH,ACF LNGO HCS,OWDA,UNISOD,DAAD,ADHOC,SAAD,KRDA 1: BACKGROUND Somali Region is one of largest regions of Ethiopia. The region comprises of nine administrative zones which in terms of livelihoods are categorised into 17 livelihood zones. The climate is mostly arid/semi-arid in lowland areas and cooler/wetter in the higher areas. Annual rainfall ranges from 150 - ~600mm per year. The region can be divided into two broader rainfall regimes based on the seasons of the year: Siti and Fafan zones to the north, and the remaining seven zones to the south. The rainfall pattern for both is bimodal but the timings differ slightly. The southern seven zones (Nogob, Jarar, Korahe, Doollo, Shabelle, Afder, Liban and Harshin District of Fafan Zone) receive ‘Gu’ rains (main season) from mid April to end of June, and secondary rains known as ‘Deyr’ from early October to late December. In the north, Siti and Fafan zones excluding Harshin of Fafan zone receive ‘Dirra’ - Objectives of the assessment also known as ‘Gu’ rains from late March To evaluate the outcome of the Deyr/Karan to late May. -

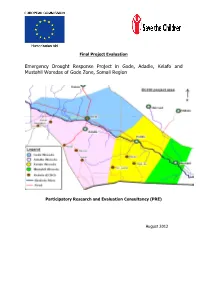

Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region

Final Project Evaluation Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region Participatory Research and Evaluation Consultancy (PRE) August 2012 Content SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................IV 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT INTERVENTION AREA ......................................................... 1 1.2 BACKGROUND TO SC UK’ S EMERGENCY DROUGHT RESPONSE ........................................ 2 2. THE FINAL EVALUATION ........................................................................................ 4 2.1 SCOPE OF THE EVALUATION .................................................................................. 4 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 Overall approach......................................................................................... 4 2.2.2 Desk review................................................................................................ 5 2.2.3 Field assessment......................................................................................... 5 2.2.4 Data collection and analysis ......................................................................... 9 3. EVALUATION FINDINGS ........................................................................................ -

(PRIME) Project Funded by the United States Agency for International Development

Pastoralist Areas Resilience Improvement through Market Expansion (PRIME) Project Funded by the United States Agency for International Development 7th Quarterly Report Year 2 – Quarter 3 Reporting Period: April 1 through June 30, 2014 Submitted to: AOR: Mohamed Abdinoor, USAID/Ethiopia Country Contact HQ contact Program Summary Karri Goeldner Byrne Nate Oetting Award No: AID-663-A-12-00014 Chief of Party Senior Program Officer Box 14319 Mercy Corps Start Date: October 15, 2012 Addis Ababa 45 SW Ankeny Ethiopia Portland, Oregon 97204 End Date: October 14, 2017 Phone:+251-(11) 416-9337 Total Award: $52,972,799 Fax: +251-(11)416-9571 503.896.5000 [email protected] [email protected] Report Date: July 31, 2014 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PRIME is a five-year, USAID-funded initiative designed to support resilience among pastoralist communities in Ethiopia, and thus enhance prospects for long-term development in Ethiopia‘s dryland landscape where the pastoralist livelihood system prevails. Financed through Feed the Future (FTF) and Global Climate Change (GCC) facilities, PRIME is designed to be transformative, innovative and achieve scale through market-driven approaches to livestock production and livelihood diversification that simultaneously support dryland communities to adapt to a changing climate. In order to achieve its overall goal of Increasing Household Incomes and Enhancing Resilience to Climate Change through Market Linkages, the program works to meet the following five major objectives (intermediate results): 1) Improved productivity and competitiveness of livestock and livestock products; 2) Enhanced pastoralists‘ adaptation to climate change; 3) Strengthened alternative livelihoods for households transitioning out of pastoralism; 4) Ensure enhanced innovation, learning and knowledge management; and 5) Improved nutritional status of targeted households improved through targeted, sustained and evidence- based interventions. -

European Academic Research, Vol III, Issue 3, June 2015 Murty, M

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. III, Issue 10/ January 2016 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org An Economic Analysis of Djibouti - Ethiopia Railway Project Dr. DIPTI RANJAN MOHAPATRA Associate Professor (Economics) School of Business and Economics Madawalabu University Bale Robe, Ethiopia Abstract: Djibouti – Ethiopia railway project is envisaged as a major export and import connection linking land locked Ethiopia with Djibouti Port in the Red Sea’s international shipping routes. The rail link is of utter significance both to Ethiopia and to Djibouti, as it would not only renovate this tiny African nation into a multimodal transport hub but also will provide competitive advantage over other regional ports. The pre-feasibility study conducted in 2007 emphasized the importance of the renovation of the project from economic and financial angle. However, as a part of GTP of Ethiopia this project has been restored with Chinese intervention. The operation expected in 2016. The proposed project is likely to provide multiple benefits such as time saving, reduction in road maintenance costs, fuel savings, employment generation, reduction in pollution, foreign exchange earnings and revenue generation. These benefits will accrue to government, passengers, general public and to society in nutshell. Here an economic analysis has been carried out to evaluate certain benefits that the project will realize against the cost streams in 25 years. The NPV of the cost streams @ 12% calculated to be 6831.30 million US$. The economic internal rate of return of investments will be 18.90 percent. Key words: EIRR, NPV, economic viability, sensitivity analysis JEL Classification: D6, R4, R42 11376 Dipti Ranjan Mohapatra- An Economic Analysis of Djibouti - Ethiopia Railway Project 1.0 INTRODUCTION: The Djibouti-Ethiopia Railway (Chemin de Fer Djibouti- Ethiopien, or CDE) Project is 784 km railway running from Djibouti to Addis Ababa via Dire Dawa. -

Grassroots Conflict Assessment of the Somali Region, Ethiopia August 2006

Ethiopia Grassroots Conflict Assessment Of the Somali Region, Ethiopia August 2006 CHF International www.chfinternational.org Table of Contents Glossary 3 Somali Region Timeline 4 Executive Summary 5 I. Purpose of the Research 7 II. Methodology 7 III. Background 9 Recent History and Governance 9 Living Standards and Livelihoods 10 Society and the Clan System 12 IV. Incentives for Violence 14 The Changing Nature of Somali Society 14 Competition Over Land 16 Other Issues of Natural Resource Management 19 Demand for Services 20 Tradition vs. Modernity 21 V. Escalation and Access to Conflict Resources 22 The Clan System as a Conflict Multiplier (and Positive Social Capital) 22 The Precarious Situation of Youth 23 Information and Misinformation 24 VI. Available Conflict Management Resources 25 Traditional Conflict Management Mechanisms and Social Capital 25 State Conflict Management Mechanisms 27 The Role of Religion and Shari’a 27 VII. Regional Dynamics 29 VIII. Window of Vulnerability: Drought and Conflict 30 IX. SWISS Mitigation Strategy 31 Engage Traditional Clan Mechanisms and Local Leaders 31 Emphasize Impartial and Secular Status 31 Seek to Carve Out a Robust Role for Women 32 Work Within Sub-Clans, not Between Them 32 Resist Efforts at Resource Co-option 32 X. Recommendations 33 Focus on Youth 33 Initiate Income-Generating Activities to Manage Environmental Degradation 34 Seek to Improve Access to Reliable Information 34 Support Transparent Land Management Mechanisms 35 Acknowledgements 36 Bibliography 37 Endnotes 39 2 Glossary (Somali -

The Role of Education in Livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia

J U N E 2 0 1 1 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice A report for the BRIDGES Project The Role of Education in Livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia Elanor Jackson ©2011 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Department for International Development as part of the BRIDGES pilot project, implemented by Save the Children UK, Mercy Corps, and Islamic Relief in the Somali Region. The author especially appreciates the support and ideas of Alison Napier of Tufts University in Addis Ababa. Thanks also to Mercy Corps BRIDGES project staff in Jijiga and Gode, Islamic Relief staff and driver in Hargelle, Save the Children UK staff in Dire Dawa, and the Tufts driver. In particular, thanks to Hussein from Mercy Corps in Jijiga for organizing so many of the interviews. Thanks also to Andy Catley from Tufts University and to Save the Children UK, Islamic Relief, Mercy Corps, and Tufts University staff in Addis Ababa for their ideas and logistical assistance. -

Resilience in Ethiopia and Somaliliand

EVALUATION: NOVEMBER 2015 PUBLICATION: JUNE 2017 RESILIENCE IN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND Impact evaluation of the reconstruction project ‘Development of Enabling Conditions for Pastoralist and Agro-Pastoralist Communities’ Effectiveness Review Series 2015/16 Photo credit: Amal Nagib/Oxfam. Women’s groups are trained on livelihood diversification, such as this tie and dye skills training in Wado makahil community,Somaliland, aimed at women producing and marketing their own garments. JONATHAN LAIN OXFAM GB www.oxfam.org.uk/effectiveness ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the staff of the partner organisations and of Oxfam in Ethiopia and Somaliland for their support in carrying out this Effectiveness Review. Particular thanks are due to Mohammed Ahmed Hussein, Million Ali and Muktar Hassan. Thanks are also due to Ahmed Abdirahman and Abdulahi Haji, for their excellent leadership of the survey process. Additionally, we are grateful to Kristen McCollum and Emily Tomkys for their support during the data collection. Finally, we thank Rob Fuller for his vital comments on earlier drafts of this report. Resilience in Ethiopia and Somaliland: Impact evaluation of the reconstruction project ‘Development of Enabling Conditions for Pastoralist and Agro-Pastoralist Communities’ Effectiveness Review Series 2015–16 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... -

Ethiopia Access Snapshot - Afar Region and Siti Zone, Somali Region As of 31 January 2020

Ethiopia Access Snapshot - Afar region and Siti zone, Somali region As of 31 January 2020 Afar region is highly prone to natural disasters Afdera The operating environment is highly compromised, with a high such as droughts and seasonal flooding. Long-- risk for humanitarian operations of becoming politicized. In ErebtiDalol Zone 2 term historical grievances coupled with Bidu March 2019, four aid workers were detained by Afar authorities TIGRAY resource-based tensions between ethnic Afar for having allegedly entered the region illegally. They were KunnebaBerahile and its neighbors i.e. Issa (Somali), and Oromo Megale conducting a humanitarian activity in Sitti zone, and decided to Teru Ittu (Amibara woreda) and Karayu (Awash Fentale woreda) in ERITREA overnight in a village of Undufo kebele. In a separate incident, in Yalo AFAR Kurri Red Sea October 2019, an attack by unidentified armed men in Afambo zone 3, and in areas adjacent to Oromia special zone and Amhara- Afdera Robe Town Aso s a Ethnic Somali IDPZone 2016/2018 4 Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Elidar region, continue to cause casualties and forced displacement, Aba 'Ala woreda, Zone 1, near Djibouti, killed a number of civilians spark- Gulina Goba Town limiting partners’ movements and operations. Overall, Ethnican Oromia IDP 2016/2018 L. Afrera Ye'ch'ew ing outrage across the region and prompting peaceful demon- Awra estimated 50,000 people remain displaced, the majority of whom Erebti strations and temporarily road blockages of the Awash highway SNNP Zone 1 Bidu rely almost entirely on assistance provided by host communities. Semera TIGRAYEwa On the other hand, in 2019, the overflow of Awash River and DJIBOUTI Clashes involving Afar and Somali Issa clan continue along Megale Afele Kola flash floods displaced some 3,300 households across six Dubti boundary areas between Afar’s zone 1 and 3 and Sitti zone.