Home and the Spirit in the Maori World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

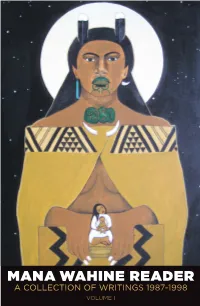

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Open Letter to Minister

14 September 2020 Attention: Minister of Education Hon Chris Hipkins [email protected] Open Letter Tēnā koe e te Rangatira, Hon Chris Hipkins, Minister of Education Māori Professors Call for a National Review of Universities We, the undersigned as Māori Professors from Aotearoa New Zealand’s Universities, write in general support of the senior Māori academics at the University of Waikato who made a protected disclosure regarding allegations of serious wrongdoing at the University of Waikato. We endorse the general observations made in public, principally concerning the Crown’s failure to protect Māori staff and students in Universities and, consequently, its failure to uphold the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi. We call for a nation-wide review of the University tertiary sector for the purpose of committing to, and accelerating with urgency, a tertiary sector that honours te Tiriti o Waitangi. We call for this nation-wide review to commence now with urgency. Signed Professor Jacinta Ruru, Professor of Law, University of Otago Professor Margaret Mutu, Professor of Māori Studies, University of Auckland Professor Jo Baxter, Professor of Hauora Māori, University of Otago Professor Antony Braithwaite, Professor of Pathology, University of Otago Emeritus Professor John Broughton, University of Otago Professor Chris Cunningham, Professor of Māori Health, Massey University Professor Meihana Durie, Professor of Māori Knowledge, Massey University Professor Jarrod Haar, Professor of Human Resource Management, Auckland University of Technology -

A Poststructural Analysis of the Health and Wellbeing of Young Lesbian Identified Women in New Zealand

A Poststructural Analysis of the Health and Wellbeing of Young Lesbian Identified Women in New Zealand. Katie Palmer du Preez A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD). 2016 Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences. School of Clinical Sciences. ABSTRACT New Zealand is regarded internationally as a forerunner in the recognition of gay rights. Despite the wide circulation of discourses of gay rights and equality, research shows that young women who identify as lesbian continue to be marginalised by society, which constrains their health and wellbeing. This study was an inquiry into the health and wellbeing of young lesbians in New Zealand, from a poststructural feminist perspective. It posed the research question: what are the discourses in play in relation to the health and wellbeing of young lesbian identified women in New Zealand? The methodology employed was a poststructural feminist discourse analysis, drawing on the philosopher Michel Foucault’s concepts of genealogy and the history of the present. Interviews with young lesbians were conducted in 2012 amid public debate around same- sex marriage. Historical data sources were the extant texts Broadsheet, a feminist periodical with strong health and wellbeing emphasis, and Hansard, a record of New Zealand parliamentary debate. Issues of these publications were selected from the early 1970s, during which the second wave feminist movement emerged, and the mid-1980s when the campaign for Homosexual Law Reform took place in New Zealand. The discourse analysis made visible the production of multiple ‘truths’ of young lesbian health and wellbeing. -

Sussing out Ageing: Sharing Lesbian & Queer Women's Knowledge Of

Sussing Out Ageing: Sharing Lesbian & Queer Women’s Knowledge of Ageing in Aotearoa New Zealand Ella J. Robinson A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand March 2019 Acknowledgements A warm thank you to all the women who took part in this project. To talk about ageing and old age is to acknowledge our own mortality. It can touch our deepest fears and stir all kinds of memories, yet you answered my questions with patience, consideration, interest and kindness. I am deeply grateful. There were so many incredible stories of courage, integrity, and compassion – I wish I could have included them all. I want to thank every single one of you, and all those who came before, who ‘took the road less travelled’ – you have made all the difference. A big thank you to all the people I met on my travels, especially my wonderful hosts in Paekākāriki and Wellington, your hospitality was more than I could ever ask for. Grandma and Grandad – thank you for nurturing your family with love, attentiveness and for passing on your passion and respect for knowledge, you are sorely missed. To Saba and Savta – thank you for your warmth, joy and teaching me the importance of connection. To my parents, Richard and Ettie – your unwavering love and support mean the world to me, I could not have done this without you. Jordan, thank you for always cheering me on. Aunty Margaret and Uncle Anaru, thank you so much for looking out for me throughout this journey, helping me feel at home in Dunedin. -

Moehewa: Death, Lifestyle & Sexuality in the Māori World

Published by Te Rau Matatini, 2016 Moehewa: Death, lifestyle & sexuality in the Māori world Volume 1 | Issue 2 same sex relationship, or for a gay, lesbian or transsexual family member. In this way, we open Article 1, December 2016 up a space for dialogue about such matters in our Linda Waimarie Nikora intimate and kin communities. University of Waikato Keywords: Māori, takatāpui, gay, lesbian, queer, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku disenfranchised grief, death rituals, bereavement, University of Waikato tangi, indigenous psychologies, end of life planning, exclusion, marginalisation. Abstract Acknowledgements. Funding support for this research was received from Nga Pae o Te Customary death ritual and traditional practice Māramatanga, the Māori Centre of Research have continued for the Māori (indigenous) people Excellence, and the Marsden Fund of the Royal of Aotearoa/New Zealand, despite intensive Society of New Zealand. Ethical approval for this missionary incursion and the colonial process. study was completed by the School of This paper critically considers what occurs when Psychology Ethical Review Committee at the the deceased is different, in a most significant University of Waikato (No. 09:31). We thank the way. What happens when you die – and you are two reviewers of this paper for their extremely Māori and any one, or a combination, of the helpful feedback. We also acknowledge the many following: a queen, takatāpui,1 butch, like that, contributors to the Tangi Research Programme gay, she-male, lesbian, transsexual, a dyke, based at the University of Waikato, New Zealand intersex, tomboy, kamp, drag, homosexual, or and remember the many who have passed over just queer? Who remembers you and how? Same and families and communities who continue to sex relationships today are still discouraged or walk with them in spirit. -

Which Wayr Mo Te Aha - Whatforr Too Ons of Maori Health: Many Questions, Not Enough Answers for Maori Ofhealth Psychology, on the March About Maori Health: ,7: 1-8

Md hea - which way? M6 te aha - what for? e analytic approach Chapter 4 .inguistica, 27: 293- lse in interpretations l for the year 2000. Ma hea - which wayr Mo te aha - whatforr Too ons of Maori health: many questions, not enough answers for Maori ofHealth Psychology, on the March about Maori health: ,7: 1-8 . .s to whet thy almost ~ology, 7: 433-451. lletin (New Zealand 'I. The Bulletin (New yity an imbalance in 'gy, 9: 293-308. e: patterns in Piikeha ? and Social Psychology, Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku School of Maori and Pacific Development, Waikato University Ire. The Bulletin, (The In M.M. Leach, M.J. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku has been a writer, cultural activist, dreamer, and social ?rnational handbook of commentator for many decades. Raised in Ohinemutu village, Rotorua, she grew up in a family of storytellers, weavers, singers. She completed her PhD in 1981, has written two Id eating kina without collections of creative fiction, and many scholarly works published here and overseas. i Psychological Society She is the principal author of the major award winning "Mau Moko: the World of Maori Tattoo". Based where she professes at the University of Waikato, she is currently co !ty Annual Conference, leading a large research team on the Maori ways of death, grief, and dying. lety), No. 99: 27-28. :huen. ,e and the legitimation of Keynote address: NZPsS Annual Conference, Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, 28 August 2004. The text ofthe address has been adapted from that published in The Bulletin ofthe New Zealand Psychological Society, No. -

Challenges, Change and Resistance

The Ethnographic Edge Contemporary Ethnography Across the Disciplines ISSN 2537-7426 Published by the Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research Journal Website http://tee.ac.nz/ Volume 4, Issue 1, 2020 Te Whakatara! – Tangihanga and bereavement COVID-19 Tess Moeke-Maxwell, Linda Waimarie Nikora, Kathleen Mason, Melissa Carey Editors: Robert E. Rinehart and Jacquie Kidd To cite this article: Moeke-Maxwell, Tess, Linda Waimarie Nikora, Kathleen Mason, and Melissa Carey. 2018. “Te Whakatara! – Tangihanga and bereavement COVID-19”. The Ethnograhic Edge 4, (1): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.15663/tee.v4i.77 To link to this volume https://doi.org/10.15663/tee.v4i Copyright of articles Creative commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Authors retain copyright of their publications. Author and users are free to: • Share—copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt—remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. • Attribution—You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use • NonCommercial—You may not use the material for commercial purposes. • ShareAlike—If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. Terms and conditions of use For full terms and conditions of use: http://tee.ac.nz/index.php/TEE/about The Ethnographic Edge Contemporary Ethnography Across the Disciplines Volume 4, 2020 Te Whakatara!—Tangihanga and bereavement COVID-19 Tess Moeke-Maxwell, Linda Waimarie Nikora, Kathleen Mason, and Melissa Carey The University of Auckland New Zealand Abstract New Zealand responded swiftly to the Covid-19 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to prevent the spread of sickness and prevent unnecessary deaths. -

Māori & Psychology Research Unit

Māori & Psychology Research Unit Annual Report 2012 © MPRU Prepared by Dr Waikaremoana Waitoki & Associate Professor Linda Waimarie Nikora, School of Psychology, University of Waikato, PB 3105, Hamilton Email: [email protected] ph: 07 856 2889 fx: 07 856 2158 http://www.waikato.ac.nz/go/mpru/ 1 Table of Contents Background .................................................................................................................... 3 Goals .............................................................................................................................. 4 MPRU Staff, Principal Investigators, Research Associates ................................................ 5 Principal Investigators ......................................................................................................... 5 Research Associates ............................................................................................................ 5 Researcher Profile: Moana Waitoki ................................................................................. 6 Master’s Student: Pare Harris ......................................................................................... 7 Student on the Rise: Stacey Ruru .................................................................................... 8 Project Review ............................................................................................................... 9 Aue Ha! Māori Men’s Relational Health ............................................................................. 9 2012 -

Aotearoa – Taiwan Human Rights Dialogue

Aotearoa – Taiwan Human Rights Dialogue Hosted by Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, Auckland University of Technology, Te Wānanga o Aotearoa DATE: Monday 10th February 2020 VENUE: Tane-nui-a-rangi, Waipapa Marae, University of Auckland TIME: 1.00pm – 5.00pm Session 1 Indigenous Taiwan / Aotearoa 1.05-2.30pm Co-Chairs Ruānuku Emeritus Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku (Aotearoa) & Professor Ford Fu Te Liao (Taiwan) Delegation Topic Speaker Aotearoa Colonial histories, resistance and pathways Dr Tiopira McDowell (NPM) forward - Aotearoa Taiwan Colonial histories, resistance and pathways Prof Jolan Hsieh / Bavaragh Dagalomai forward - Taiwan (Taiwan) Aotearoa Persistent challenges : Racism and Equity Prof Papaarangi Reid (NPM) Taiwan Indigenous youth and health in Taiwan Assistant Prof Ciwang Teyra (Taiwan) Open floor discussion (Q&A) 2.30-3.00pm Informal Discussion, Tea Break Session 2 Human Rights Challenges 3.00pm – 4.45pm Co-Chairs Professor Linda Waimarie Nikora (Aotearoa) & Professor Jolan Hsieh / Bavaragh Dagalomai (Taiwan) Delegation Topic Speaker Aotearoa Te Reo Maori revitalization Dr Morehu McDonald (NPM-TWoA) Taiwan Taiwan Indigenous language revitalisation Assistant Prof Ciwas Pawan (Taiwan) Aotearoa Human right to hygiene and sanitation Dr Shiloh Groot (Pacific/NPM) Pacific Mental health is a human right Dr Jemaima Tiatia (Pacific) Open floor discussion 4.45pm Karakia, Kua mutu SPEAKER PROFILES Ford Fu-Te Liao President, Taiwan Foundation for Democracy Researcher, Law Institute of Academia Sinica D. Phil. in Law, Oxford University (UK) Bavaragh Dagalomai | Advisor, Presidential Office’s Historical and Transitional Justice HSIEH, Jolan Committee // Convener of Subcommittee on Reconciliation Professor of Dept. Of Ethnic Relations and Cultures // Director of Siraya Center for International Indigenous Affairs, College of Indigenous Studies, National Dong Hwa University Ph.D in Justice Studies, Arizona State University (USA) Ciwang Teyra Assistant Professor, Dept. -

MODERN MOKO and WESTERN SUBCULTURE a Thesis Submitted

CHALLENGING APPROPRIATION: MODERN MOKO AND WESTERN SUBCULTURE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts By Ridgely Dunn May, 2011 Thesis Written By Ridgely Dunn B.A. University of Illinois, 2005 M.A. Kent State University, 2011 Approved by ______________________________________, Director, Master‟s Thesis Committee Richard Feinberg ______________________________________, Member, Master‟s Thesis Committee Mark Seeman ______________________________________, Member, Master‟s Thesis Committee Richard Serpe Accepted by ______________________________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Richard S. Meindl ______________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences John Stalvey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION. 1 The Tattoo and Moko in History . 2 Statement of Intent . 3 Modern Primitivism and body modification practices in the West . 6 Basis and scope of research topic . 8 Challenges to the research . 10 The Importance of Self and Identity . 15 2 THE BRIEF HISTORY OF TA MOKO IN NEW ZEALAND . 19 The Role of Mana and Tapu in Moko . 23 The Role of the Tohunga tā Moko . 27 The Decline of Moko . 31 Mokomokai . 32 Gender and Moko . 34 3 UNCONVENTIAL METHODS OF CULTURAL PRESERVATION . 39 Women and Moko . 41 The Role of Gangs in Moko Preservation . 44 Rasta and Moko . 46 Mainstreaming Moko . 47 Moko as Part of Pacific Islander Identity . 51 Moko as a Part of Biculturalism . 53 Conclusion . 56 4 MODERN PRIMITIVE IDENTITIES AND MĀORI TRADITIONS. 59 Modern Primitive History . 62 Structure in the Modern Primitive Subculture . 64 Modification as Ritual and Rite of Passage . 66 iii Individual Versus Group Identification . -

Opening Address

Claiming Spaces: Proceedings of the 2007 National Maori and Pacific Psychologies Symposium 23rd-24th November 2007 Hosted by: The Maori and Psychology Research Unit University of Waikato Hamilton Edited by: Michelle Levy Linda Waimarie Nikora Bridgette Masters-Awatere Mohi Rua Waikaremoana Waitoki The Maori & Psychology Research Unit University of Waikato Hamilton, New Zealand Claiming Spaces: Proceedings of the 2007 National Maori and Pacific Psychologies Symposium Copyright © Maori and Psychology Research Unit, University of Waikato 2008 Each contributor has permitted the Maori and Psychology Research Unit to publish their work in this collection. No part of the material protected in this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the contributor concerned. ISBN: 978‐0‐473‐13577‐5 Title: Claiming Spaces: Proceedings of the 2007 National Maori and Pacific Psychologies Symposium, 23‐24 November, Hamilton. Publication Date: November 2008 Publisher’s Name: Maori and Psychology Research Unit, University of Waikato Publishers Address: Private Bag 3105, Hamilton Publishers Phone: 07 8562889 Publishers Fax: 07 8585132 Contact Email: [email protected] Web: http://trak.to/mpru/ Editors: Levy, M., Nikora, L.W., Masters‐Awatere, B., Rua, M.R., Waitoki, W. Editors Note: With respect to the use of macrons, papers have been published as submitted by authors. Claiming Spaces: Proceedings of the 2007 National Maori and Pacific Psychologies Symposium Page 1 Acknowledgements Acknowledgements A number of people and organisations have contributed to the hosting of the 2007 National Maori and Pacific Psychologies Symposium. -

Cold Islanders

Cold Islanders Moana Pasifika/Oceania identified artists creating and occupying respectful stances of strength and confidence in Aotearoa Olga H J Wilson A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) Te Ara Poutama Auckland University of Technology 2020 Chief Supervisor: Emeritus Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku Secondary Supervisor: Professor Waimarie Linda Nikora 1 Lotu - Karakia Creator God May those needing to find safe waters be comforted by the words that spring from your Source. In the deep dark waters may they find you And in the ninth heavens may they find you And in primordial time and space May they find themselves. Three Oceans around the Vā, Te Whenua and Le Fanua Guide us to a spacious place upon which to stand. 2 Table of Contents Karakia……………………………………………………………………………………….………..2 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…….…6 List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………………………7 List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………….…..9 List of Appendices.……………………………………………………………….…………………..10 List of Abbreviations, Terminologies…………………………………………….……………….......11 Glossary…………………………………………………………………………………………….…12 Attestation of Authorship………………………………………………………………………..........15 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………...16 Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..…...18 Research Purpose …………………………………………………………………………………......18 Research Questions…………………………………………………………………………………...19 Looking Back to Move Forward………………………………………………………………….......19