Memento Mori : Memento Maori – Moko and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/18/35/Add.4 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/18/35/Add.4 General Assembly Distr.: General 31 May 2011 Original: English Human Rights Council Eighteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya Addendum The situation of Maori people in New Zealand∗ Summary In the present report, which has been updated since the advance unedited version was made public on 17 February 2011, the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples examines the situation of Maori people in New Zealand on the basis of information received during his visit to the country from 18-23 July 2010 and independent research. The visit was carried out in follow-up to the 2005 visit of the previous Special Rapporteur, Rodolfo Stavenhagen. The principal focus of the report is an examination of the process for settling historical and contemporary claims based on the Treaty of Waitangi, although other key issues are also addressed. Especially in recent years, New Zealand has made significant strides to advance the rights of Maori people and to address concerns raised by the former Special Rapporteur. These include New Zealand’s expression of support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, its steps to repeal and reform the 2004 Foreshore and Seabed Act, and its efforts to carry out a constitutional review process with respect to issues related to Maori people. Further efforts to advance Maori rights should be consolidated and strengthened, and the Special Rapporteur will continue to monitor developments in this regard. -

Mauri Monitoring Framework. Pilot Study on the Papanui Stream

Te Hā o Te Wai Māreparepa “The Breath of the Rippling Waters” Mauri Monitoring Framework Pilot Study on the Papanui Stream Report Prepared for the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council Research Team Members Brian Gregory Dr Benita Wakefield Garth Harmsworth Marge Hape HBRC Report No. SD 15-03 Joanne Heperi HBRC Plan No. 4729 2 March 2015 (i) Ngā Mihi Toi tü te Marae a Tane, toi tü te Marae a Tangaroa, toi tü te iwi If you preserve the integrity of the land (the realm of Tane), and the sea (the realm of Tangaroa), you will preserve the people as well Ka mihi rā ki ngā marae, ki ngā hapū o Tamatea whānui, e manaaki ana i a Papatūānuku, e tiaki ana i ngā taonga a ō tātau hapu, ō tātau iwi. Ka mihi rā ki ngā mate huhua i roro i te pō. Kei ngā tūpuna, moe mai rā, moe mai rā, moe mai rā. Ki te hunga, nā rātau tēnei rīpoata. Ki ngā kairangahau, ka mihi rā ki a koutou eū mārika nei ki tēnei kaupapa. Tena koutou. Ko te tūmanako, ka ora nei, ka whai kaha ngāwhakatipuranga kei te heke mai, ki te whakatutuki i ngā wawata o kui o koro mā,arā, ka tū rātau hei rangatira mō tēnei whenua. Tena koutou, tena koutou, tena koutou katoa Thanks to the many Marae, hapū, from the district of Tamatea for their involvement and concerns about the environment and taonga that is very precious to their iwi and hapū. Also acknowledge those tūpuna that have gone before us. -

Ngāiterangi Treaty Negotiations: a Personal Perspective

NGĀITERANGI TREATY NEGOTIATIONS: A PERSONAL PERSPECTIVE Matiu Dickson1 Treaty settlements pursuant to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi can never result in a fair deal for Māori who seek justice against the Crown for the wrongs committed against them. As noble the intention to settle grievances might be, at least from the Crown’s point of view, my experience as an Iwi negotiator is that we will never receive what we are entitled to using the present process. Negotiations require an equal and honest contribution by each party but the current Treaty settlements process is flawed in that the Crown calls the shots. To our credit, our pragmatic nature means that we accept this and move on. At the end of long and sometimes acrimonious settlement negotiations, most settlements are offered with the caveat that as far as the Crown is concerned, these cash and land compensations are all that the Crown can afford so their attitude is “take it or leave it”. If Māori do not accept what is on offer, then they have to go to the back of the queue. The process is also highly politicised so that successive Governments are not above using the contentious nature of settlements for their political gain, particularly around election time. To this end, Governments have indicated that settlements are to be concluded in haste, they should be full and final and that funds for settlements are capped. These are hardly indicators of equal bargaining power and good faith, which are the basic principles of negotiation. As mentioned, the ‘negotiations’ are not what one might consider a normal process in that, normally, parties are equals in the discussions. -

Cultural Impact Assessment Report Te Awa Lakes Development

Cultural Impact Assessment Report Te Awa Lakes Development 9 October 2017 Document Quality Assurance Bibliographic reference for citation: Boffa Miskell Limited 2017. Cultural Impact Assessment Report: Te Awa Lakes Development. Report prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited for Perry Group Limited. Prepared by: Norm Hill Kaiarataki - Te Hihiri / Strategic Advisor Boffa Miskell Limited Status: [Status] Revision / version: [1] Issue date: 9 October 2017 Use and Reliance This report has been prepared by Boffa Miskell Limited on the specific instructions of our Client. It is solely for our Client’s use for the purpose for which it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. Boffa Miskell does not accept any liability or responsibility in relation to the use of this report contrary to the above, or to any person other than the Client. Any use or reliance by a third party is at that party's own risk. Where information has been supplied by the Client or obtained from other external sources, it has been assumed that it is accurate, without independent verification, unless otherwise indicated. No liability or responsibility is accepted by Boffa Miskell Limited for any errors or omissions to the extent that they arise from inaccurate information provided by the Client or any external source. Template revision: 20171010 0000 File ref: H17023_Te_Awa_Lakes_Cultural_Impact_.docx Protection of Sensitive Information The Tangata Whenua Working Group acknowledges and supports s42 of the Resource Management Act 1991, which effectively protects intellectual property and sensitive information. As a result, the Tangata Whenua Working Group may request that evidence provided at a subsequent hearing be held in confidence by the Council. -

Workingpaper

working paper The Evolution of New Zealand as a Nation: Significant events and legislation 1770–2010 May 2010 Sustainable Future Institute Working Paper 2010/03 Authors Wendy McGuinness, Miriam White and Perrine Gilkison Working papers to Report 7: Exploring Shared M āori Goals: Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy and Report 8: Effective M āori Representation in Parliament: Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy Prepared by The Sustainable Future Institute, as part of Project 2058 Disclaimer The Sustainable Future Institute has used reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Published Copyright © Sustainable Future Institute Limited, May 2010 ISBN 978-1-877473-55-5 (PDF) About the Authors Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the Sustainable Future Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. -

The Waikato-Tainui Settlement Act: a New High-Water Mark for Natural Resources Co-Management

Notes & Comments The Waikato-Tainui Settlement Act: A New High-Water Mark for Natural Resources Co-management Jeremy Baker “[I]f we care for the River, the River will continue to sustain the people.” —The Waikato-Tainui Raupatu Claims (Waikato River) Settlement Act 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 165 II. THE EMERGENCE OF ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT ......................... 166 A. Co-management .................................................................... 166 B. Adaptive Management .......................................................... 168 C. Fusion: Adaptive Co-management ....................................... 169 D. Some Criticisms and Challenges Associated with Adaptive Co-management .................................................... 170 III. NEW ZEALAND’S WAIKATO-TAINUI SETTLEMENT ACT 2010—HISTORY AND BACKGROUND ...................................... 174 A. Maori Worldview and Environmental Ethics ....................... 175 B. British Colonization of Aotearoa New Zealand and Maori Interests in Natural Resources ............................ 176 C. The Waikato River and Its People ........................................ 182 D. The Waikato River Settlement Act 2010 .............................. 185 Jeremy Baker is a 2013 J.D. candidate at the University of Colorado Law School. 164 Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y [Vol. 24:1 IV. THE WAIKATO-TAINUI SETTLEMENT ACT AS ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT .......................................................................... -

Project Proposal Template A

Project Proposal Template A. TITLE OF PROJECT Tūhonohono: Tikanga Māori me te Ture Pākehā ki Takutai Moana (“Tūhonohono”) B. IDENTIFICATION Project Leader: Dr Robert Joseph (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Kahungunu, Rangitāne, Ngāi Tahu), Te Mata Hautū Taketake – the Māori and Indigenous Governance Centre (“MIGC”), Te Piringa-Faculty of Law, University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 [email protected] (07) 838 4466 extn 8796; Cell (022) 070 3275 Co-researchers, Professor Jacinta Ruru (Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Ranginui), Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga (“Ngā Pae”); Associate Professor Sandy Morrison (Ngāti Rarua, Ngāti Maniapoto, Te Arawa) and Professor Linda Smith (Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Porou), Te Pua Wānanga ki te Ao, Ms Valmaine Toki (Ngāti Wai) and Ms Mylene Rakena (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngapuhi) MIGC, Waikato University. Co-production of research with Frank Hippolite and others, Tiakina te Taiao Ltd (“Tiakina”), representing Ngāti Rarua Iwi Trust, Ngāti Koata Trust, Ngāti Rarua-Te Atiawa Trust Board, Wakatu Inc., Ngāti Tama ki te Waipounamu and Te Atiawa o te Waka-A-Maui. Investigators: PhD students - Ms Adrienne Paul (Ngāti Awa) MIGC, Waikato University and Paul Meredith (Ngāti Maniapoto) University of Victoria, Wellington. Student researchers - Mr Hemi Arthur (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Koata, Te Atiawa) and Apirana Daymond (Ngāti Mutunga (Chatham Islands) and Ngāti Porou). Advisory Assistance MIGC, University of Waikato (UOW) Advisory assistance – Professor Barry Barton, Professor Al Gillespie, Associate Professor Linda Te Aho, Professor Pou Temara, Tom Roa and Trevor Daya- Winterbottom. C. ABSTRACT Prior to European contact, Māori had effective legal systems based on mātauranga and tikanga Māori – Māori laws and institutions - which were very effective for social control and for maintaining law and order, and which developed into a considerable body of knowledge and practices over time. -

TRANSCRIPT of PROCEEDINGS BOARD of INQUIRY Proposed

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS BOARD OF INQUIRY Proposed Ruakura Development Plan Change HEARING at KINGSGATE HOTEL, HAMILTON on 6 June 2014 BOARD OF INQUIRY: Judge Melanie Harland (Chairperson) Mr Jim Hodges (Board Member) Ms Jenny Hudson (Board Member) Mr Gerry Te Kapa Coates (Board Member) Page 1702 APPEARANCES <DIANA CHRISTINE WEBSTER, affirmed [2.25 pm] ......................... 1773 <THE WITNESS WITHDREW [3.24 pm] ....................................... 1794 5 Kingsgate Hotel, Hamilton 03.06.14 Page 1703 [9.21 am] CHAIRPERSON: Thank you. Nga mihi nui kia koutou, good morning to everyone. We are just about to start this morning with hearing from 5 some of our submitters and I understand that there is to be a slight change in order and we are starting with Miss van Beek first, thank you. MISS VAN BEEK: Good morning. 10 CHAIRPERSON: Good morning, just when you are ready. MISS VAN BEEK: Hello, my name is Anita van Beek and I am just doing my own personal kind of feelings about this submission. So I am not 15 possibly the best prepared for talking here as I have tried to read and understand some of the stuff and it has all been a bit gobbledygook, unless someone was there to explain some of it. So I haven’t have had a lot of time to read all of it, there’s busy jobs and things like that in my own life. 20 So basically this is kind of more my feelings. So, for example, some of the simple things like a “transportation corridor” I interpreted as “roads” but wondered if there was any difference between the two, sometimes it seemed like French to me. -

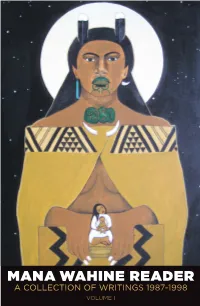

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Open Letter to Minister

14 September 2020 Attention: Minister of Education Hon Chris Hipkins [email protected] Open Letter Tēnā koe e te Rangatira, Hon Chris Hipkins, Minister of Education Māori Professors Call for a National Review of Universities We, the undersigned as Māori Professors from Aotearoa New Zealand’s Universities, write in general support of the senior Māori academics at the University of Waikato who made a protected disclosure regarding allegations of serious wrongdoing at the University of Waikato. We endorse the general observations made in public, principally concerning the Crown’s failure to protect Māori staff and students in Universities and, consequently, its failure to uphold the principles of te Tiriti o Waitangi. We call for a nation-wide review of the University tertiary sector for the purpose of committing to, and accelerating with urgency, a tertiary sector that honours te Tiriti o Waitangi. We call for this nation-wide review to commence now with urgency. Signed Professor Jacinta Ruru, Professor of Law, University of Otago Professor Margaret Mutu, Professor of Māori Studies, University of Auckland Professor Jo Baxter, Professor of Hauora Māori, University of Otago Professor Antony Braithwaite, Professor of Pathology, University of Otago Emeritus Professor John Broughton, University of Otago Professor Chris Cunningham, Professor of Māori Health, Massey University Professor Meihana Durie, Professor of Māori Knowledge, Massey University Professor Jarrod Haar, Professor of Human Resource Management, Auckland University of Technology -

Methodist Conference 2014 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa

Methodist Conference 2014 Te Háhi Weteriana O Aotearoa CONFERENCE SUMMARY - A time to sow, a time to grow - The Annual Conference of the Methodist Church of New Zealand met in Hamilton at Wintec from Saturday 15 November until Wednesday 19 November 2014 The intention of this record is to provide Conference delegates with summary material to report back to their congregations. This needs to be read in conjunction with the Conference sheets, where full lists of people involved, roles, and appointments will be found. That material and the formal record of decisions and minutes taken by Conference secretaries takes precedence over these more informal notes, for historical and legal purposes! Rev Alan K Webster: Media Officer Conference 2014 Full proceedings and formal records of conference decisions are available on the Methodist website, http://www.methodist.org.nz/conference/2014 Formal guests of Conference included: Rev Dr Finau Ahio, President Free Wesleyan Church of Tonga Rev Aisoli Tapa Iuli, President of the Methodist Church of Samoa Rev Epinieri Vakadewavosa, General Secretary Elect, Methodist Church of Fiji Rev Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, Bishop of Waikato Natasha Klukach, World Council of Churches Programme Executive for Church Relations Observers from Other Churches Margaret Whiting, Presbyterian Church Deacon Peter Richardson, Roman Catholic Church Page 1 FRIDAY Stationing Committee met. Wesley Historical Society met for their AGM, where Helen Laurenson was re-elected as President, and we enjoyed a presentation from Rev Dr Allan Davidson on the Methodist Church and World War One. SATURDAY Service to honour those who have died Induction of President Rev Tovia Aumua and Vice President Dr Arapera Ngaha. -

Home and the Spirit in the Maori World

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Research Commons@Waikato Home and the Spirit in the Maori World Home and the Spirit in the Maori World Associate Professor Linda Waimarie Nikora Professor Ngahuia Te Awekotuku Dr Virginia Tamanui Contact author: Linda Waimarie Nikora Email: [email protected] Nikora, L., Te Awekotuku, N., & Tamanui, V. (2013). Home and the Spirit in the Maori World. Paper presented at the He Manawa Whenua Conference, University of Waikato, Hamilton. Nikora, Te Awekotuku and Tamanui (2013) 1 Home and the Spirit in the Maori World Today we explore home as a place of spiritual belonging and continuity and how tangi relies on the genealogical connectedness of ancestral and living communities to care for the tūpāpaku, the human remains, and wairua, the spirit of the deceased, as well as the living. While colonisation and westernisation have changed us, the institution of tangi, our rituals of death and mourning, have remained since pre-encounter times. In the face of death, tangi and its repetitive ritualised pattern of encounter and mourning might be viewed as a lifeline to hold on to as the disturbance and turmoil spawned by death is endured. We begin this paper by returning to the beginning, the place of potentiality to contemplate our spiritual origins and life endowments. We consider the nature of Māori beliefs about a spiritual afterlife and how through the institution of tangi we guide and support the departing spirit on its way. We argue that these rituals of departure and support are most optimally performed within the context of our marae and spiritual landscapes.