The Evolution of Closed-Mouth Vocal Behavior in Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report the Drongos Last Won the 30Hr Race Back in 2017 and It Was Great Getting That Team Back Together Again

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report The Drongos last won the 30hr race back in 2017 and it was great getting that team back together again. Maxie the Co-pilot and Simon ‘The Whisperer’ joined the Capt’n for a week of birding out west before heading to our starting point in the mulga. It is here I should mention that the area is currently seeing an absolute boom period after recent rains and was heaving with birds. So with this in mind and with our proven ‘golden route’ we were quite confident of scoring a reasonably good score. We awoke to rain on tin and it didn’t stop as we drove to the mulga, in fact it got heavier.As we sat in the car with 20min until start time we were contemplating if this would kill our run. But as we walked around in the drizzle we soon realised the birds were still active. Simon found a family of Inland Thornbill (a bird I always like to start with), Max had found a roosting Hobby and I’d found some Bee-eaters and Splendid Fairywrens. As the alarm chimed we quickly ticked up all those species as well as Red-capped Robin, Masked and White-browed Woodswallow, Black Honeyeater, White-winged Triller and Budgerigar. The Little Eagle was still on it’s nest and a pair of Plum-headed Finches shot past. We then changed location within the mulga and soon flushed a Little Buttonquail!! Common Bronewing, Owlet-nightjar and Mulga Parrot soon fell and after 20min we were off. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Brookfield CP Bird List

Bird list for BROOKFIELD CONSERVATION PARK -34.34837 °N 139.50173 °E 34°20’54” S 139°30’06” E 54 362200 6198200 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Rainbow Bee-eater Mulga Parrot Eastern Bluebonnet Red-rumped Parrot Australian Boobook *Feral Pigeon Common Bronzewing Crested Pigeon Australian Bustard Spur-winged Plover Little Buttonquail (Masked Lapwing) Painted Buttonquail Stubble Quail Cockatiel Mallee Ringneck Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Australian Ringneck) Little Corella Yellow Rosella Black-eared Cuckoo (Crimson Rosella) Fan-tailed Cuckoo Collared Sparrowhawk Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Grey Teal Pallid Cuckoo Shining Bronze Cuckoo Peaceful Dove Maned Duck Pacific Black Duck Little Eagle Wedge-tailed Eagle Emu Brown Falcon Peregrine Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Galah Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe Spotted Harrier White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Nankeen Kestrel Red-backed Kingfisher Black Kite Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite Laughing Kookaburra Banded Lapwing Musk Lorikeet Purple-crowned Lorikeet Malleefowl Spotted Nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Blue-winged Parrot Elegant Parrot If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. SEASONS – Spring: September, October, November; Summer: December, January, February; Autumn: March, April May; Winter: June, July, August IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ONLY BIRDS SEEN WITHIN THE RESERVE ARE RECORDED ON THIS LIST. -

2015 QUEENSLAND TWITCHATHON 18 - 28 September 2015

2015 QUEENSLAND TWITCHATHON 18 - 28 September 2015 IOC Alphabetical Checklist of the Birds of Queensland: Source http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist. Team Name: Race Category: Total Number of Species: Photographic Category Only. Photos vetted by: Results (number of counted species) must be received by phone (0488 636 010) by 8pm Monday 28 September. Results (this list with counted species marked) must be received by email to [email protected] by 8pm Friday, 2 October. Column1 Column2 Column3 1 Albert's Lyrebird 2 Apostlebird 3 Arafura Fantail 4 Atherton Scrubwren 5 Australasian Bittern 6 Australasian Darter 7 Australasian Figbird 8 Australasian Gannet 9 Australasian Grebe 10 Australasian Shoveler 11 Australian Brushturkey 12 Australian Bustard 13 Australian Crake 14 Australian Golden Whistler 15 Australian Hobby 16 Australian King Parrot 17 Australian Logrunner 18 Australian Magpie 19 Australian Masked Owl 20 Australian Owlet-nightjar 21 Australian Painted-snipe 22 Australian Pelican 23 Australian Pied Cormorant 24 Australian Pipit 25 Australian Pratincole 26 Australian Raven 27 Australian Reed Warbler 28 Australian Ringneck 1/11 Column1 Column2 Column3 29 Australian Shelduck 30 Australian Swiftlet 31 Australian White Ibis 32 Azure Kingfisher 33 Baillon's Crake 34 Banded Honeyeater 35 Banded Lapwing 36 Banded Stilt 37 Banded Whiteface 38 Bar-breasted Honeyeater 39 Bar-shouldered Dove 40 Bar-tailed Godwit 41 Barking Owl 42 Barn Swallow 43 Barred Cuckooshrike 44 Bassian Thrush 45 Beach Stone-curlew 46 Bell Miner 47 Black Bittern -

Western Australia

WESTERN AUSTRALIA 16 AUGUST – 7 SPETEMBER 2003 TOUR REPORT LEADER: CHRIS DOUGHTY. Seven years of drought in Australia has finally ended, unfortunately, the drought ended when the group arrived in Albany where we experienced heavy rain and gale force winds. Although we left the rain behind in Albany, the strong winds persisted throughout the whole tour, making the birding more difficult. After a leisurely first afternoon recovering from our long-haul flights, we began our birding the next morning at Lake Monger in the pleasant suburbs of Perth. The large concentrations of waterbirds included a few pairs of the uncommon Blue-billed Duck, several bizarre Musk Ducks, including a male bird, which put on an equally bizarre courtship display, and rather more surprisingly, a small party of Short-billed Black-Cockatoos, a south-western endemic which does not normally occur in downtown Perth. Here we also encountered our first honeyeaters, including the striking White-cheeked Honeyeater. As we drove on south towards Narrogin, we came across another of the south-western endemics, a splendid, full-plumaged, male Western Rosella, perched obligingly in a dead tree by the roadside. In the afternoon, a visit to Dryandra State Forest produced three more south-western endemics: Red-capped Parrot, Rufous Treecreeper and Western Yellow Robin. However, the afternoon’s show was undoubtedly stolen by a couple of seriously endangered Numbats, which gave superb views as they foraged busily on the forest floor only metres from the bus. This once widespread marsupial ‘ground squirrel’ is now confined to Dryandra State Forest. We also enjoyed great looks at a couple of obliging Short- beaked Echidnas, with a supporting cast of several Western Grey Kangaroos. -

Coos, Booms, and Hoots: the Evolution of Closed-Mouth Vocal Behavior in Birds

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12988 Coos, booms, and hoots: The evolution of closed-mouth vocal behavior in birds Tobias Riede, 1,2 Chad M. Eliason, 3 Edward H. Miller, 4 Franz Goller, 5 and Julia A. Clarke 3 1Department of Physiology, Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas 78712 4Department of Biology, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador A1B 3X9, Canada 5Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 84112, Utah Received January 11, 2016 Accepted June 13, 2016 Most birds vocalize with an open beak, but vocalization with a closed beak into an inflating cavity occurs in territorial or courtship displays in disparate species throughout birds. Closed-mouth vocalizations generate resonance conditions that favor low-frequency sounds. By contrast, open-mouth vocalizations cover a wider frequency range. Here we describe closed-mouth vocalizations of birds from functional and morphological perspectives and assess the distribution of closed-mouth vocalizations in birds and related outgroups. Ancestral-state optimizations of body size and vocal behavior indicate that closed-mouth vocalizations are unlikely to be ancestral in birds and have evolved independently at least 16 times within Aves, predominantly in large-bodied lineages. Closed-mouth vocalizations are rare in the small-bodied passerines. In light of these results and body size trends in nonavian dinosaurs, we suggest that the capacity for closed-mouth vocalization was present in at least some extinct nonavian dinosaurs. As in birds, this behavior may have been limited to sexually selected vocal displays, and hence would have co-occurred with open-mouthed vocalizations. -

Native Animal Species List

Native animal species list Native animals in South Australia are categorised into one of four groups: • Unprotected • Exempt • Basic • Specialist. To find out the category your animal is in, please check the list below. However, Specialist animals are not listed. There are thousands of them, so we don’t carry a list. A Specialist animal is simply any native animal not listed in this document. Mammals Common name Zoological name Species code Category Dunnart Fat-tailed dunnart Sminthopsis crassicaudata A01072 Basic Dingo Wild dog Canis familiaris Not applicable Unprotected Gliders Squirrel glider Petaurus norfolcensis E04226 Basic Sugar glider Petaurus breviceps E01138 Basic Possum Common brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula K01113 Basic Potoroo and bettongs Brush-tailed bettong (Woylie) Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi M21002 Basic Long-nosed potoroo Potorous tridactylus Z01175 Basic Rufous bettong Aepyprymnus rufescens W01187 Basic Rodents Mitchell's hopping-mouse Notomys mitchellii Y01480 Basic Plains mouse (Rat) Pseudomys australis S01469 Basic Spinifex hopping-mouse Notomys alexis K01481 Exempt Wallabies Parma wallaby Macropus parma K01245 Basic Red-necked pademelon Thylogale thetis Y01236 Basic Red-necked wallaby Macropus rufogriseus K01261 Basic Swamp wallaby Wallabia bicolor E01242 Basic Tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii eugenii C05889 Basic Tasmanian pademelon Thylogale billardierii G01235 Basic 1 Amphibians Common name Zoological name Species code Category Southern bell frog Litoria raniformis G03207 Basic Smooth frog Geocrinia laevis -

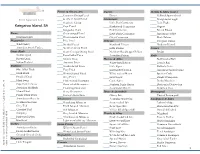

Bird Species Checklist

Petrels & Shearwaters Darters Hawks & Allies (cont.) Common Diving-Petrel Darter Collared Sparrowhawk Bird Species List Southern Giant Petrel Cormorants Wedge-tailed Eagle Southern Fulmar Little Pied Cormorant Little Eagle Kangaroo Island, SA Cape Petrel Black-faced Cormorant Osprey Kerguelen Petrel Pied Cormorant Brown Falcon Emus Great-winged Petrel Little Black Cormorant Australian Hobby Mainland Emu White-headed Petrel Great Cormorant Black Falcon Megapodes Blue Petrel Pelicans Peregrine Falcon Wild Turkey Mottled Petrel Fiordland Pelican Nankeen Kestrel Australian Brush Turkey Northern Giant Petrel Little Pelican Cranes Game Birds South Georgia Diving Petrel Northern Rockhopper Pelican Brolga Stubble Quail Broad-billed Prion Australian Pelican Rails Brown Quail Salvin's Prion Herons & Allies Buff-banded Rail Indian Peafowl Antarctic Prion White-faced Heron Lewin's Rail Wildfowl Slender-billed Prion Little Egret Baillon's Crake Blue-billed Duck Fairy Prion Eastern Reef Heron Australian Spotted Crake Musk Duck White-chinned Petrel White-necked Heron Spotless Crake Freckled Duck Grey Petrel Great Egret Purple Swamp-hen Black Swan Flesh-footed Shearwater Cattle Egret Dusky Moorhen Cape Barren Goose Short-tailed Shearwater Nankeen Night Heron Black-tailed Native-hen Australian Shelduck Fluttering Shearwater Australasian Bittern Common Coot Maned Duck Sooty Shearwater Ibises & Spoonbills Buttonquail Pacific Black Duck Hutton's Shearwater Glossy Ibis Painted Buttonquail Australasian Shoveler Albatrosses Australian White Ibis Sandpipers -

Management of the Houtman Abrolhos System

MANAGEMENT OF THE HOUTMAN ABROLHOS SYSTEM A DRAFT REVIEW 2007 - 2017 Prepared on behalf of the Minister for Fisheries by the Department of Fisheries (Western Australia) on advice from the Abrolhos Islands Management Advisory Committee FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PAPER No. 220 Published by Department of Fisheries 168 St. Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000 February 2007 ISSN 0819-4327 Fisheries Management Paper No. 220 Management of the Houtman Abrolhos System A Draft Review 2007 to 2017 Prepared on behalf of the Minister for Fisheries by the Department of Fisheries (Western Australia) on advice from the Abrolhos Islands Management Advisory Committee February 2007 Fisheries Management Paper No. 220 ISSN 0819-4327 2 Fisheries Management Paper No. 220 CONTENTS OPPORTUNITY TO COMMENT ...........................................................................................................5 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................7 1.1 MAJOR MANAGEMENT AND KEY STRATEGIC ISSUES ...................................................................7 1.2 ABROLHOS ISLANDS GOVERNANCE..............................................................................................8 1.3 MANAGEMENT OF THE ABROLHOS SYSTEM (FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PAPER 117)........................9 1.4 AIM OF THE ABROLHOS ISLANDS STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT PLAN ...........................................10 1.4.1 Conservation Values.......................................................................................................10 -

Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Flyway Partnership Report

Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Flyway Partnership Report Report by The Nature Conservancy For the: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia 27 March 2018 The lead author of this document was David Mehlman of The Nature Conservancy’s Migratory Bird Program, with significant input, editing, and other assistance from James Fitzsimons and Anita Nedosyko of The Nature Conservancy’s Australia Program and Boze Hancock from The Nature Conservancy’s Global Oceans Team. Acknowledgements We thank the Government of South Australia, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, for funding this work under an agreement with The Nature Conservancy Australia. Helpful advice and comments on various aspects of this project were received from Mark Carey, Tony Flaherty, Rich Fuller, Michaela Heinson, Arkellah Irving, Jason Irving, Micha Jackson, Spike Millington, Chris Purnell, Phil Straw, Connie Warren, Doug Watkins, and Dan Weller. 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ 4 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Overview of the Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary .............................................................................. -

Download the Bird List

Bird list for MESSENT CONSERVATION PARK -36.05729 °N 139.77199 °E 35°03’26” S 139°46’19” E 54 389400 6090000 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Red-necked Avocet Laughing Kookaburra Rainbow Bee-eater Banded Lapwing Eastern Bluebonnet Musk Lorikeet Australian Boobook Purple-crowned Lorikeet Brush Bronzewing Malleefowl Common Bronzewing Black-tailed Nativehen Little Buttonquail Spotted Nightjar Painted Buttonquail Eastern Barn Owl Cockatiel Australian Owlet-nightjar Great Cormorant Blue-winged Parrot Little Black Cormorant Elegant Parrot Pied Cormorant Red-rumped Parrot Australian Crake Australian Pelican Fan-tailed Cuckoo Crested Pigeon Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo *Feral Pigeon Pallid Cuckoo Red-capped Plover Black-fronted Dotterel Spur-winged Plover Red-kneed Dotterel (Masked Lapwing) Peaceful Dove Brown Quail Blue-billed Duck Stubble Quail Maned Duck Mallee Ringneck Musk Duck (Australian Ringneck) Pacific Black Duck Crimson Rosella Wedge-tailed Eagle Eastern Rosella Great Egret Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Emu Australian Shelduck Brown Falcon Latham's Snipe Peregrine Falcon Collared Sparrowhawk Tawny Frogmouth Royal Spoonbill Galah Yellow-billed Spoonbill Brown Goshawk Pied Stilt Australasian Grebe Black Swan Great Crested Grebe Chestnut Teal Hoary-headed Grebe Grey Teal Silver Gull Whiskered Tern Hardhead Spotted Harrier Swamp Harrier Nankeen Night Heron White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Australian White Ibis Nankeen Kestrel Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. -

Ebird Field Checklist

Parrots, Parakeets, and Allies Vultures, Hawks, and Allies Australian King-Parrot Black-shouldered Kite Swift Parrot Little Eagle Crimson Rosella Wedge-tailed Eagle Eastern Rosella Swamp Harrier Red-rumped Parrot Spotted Harrier 191 species (+4 other taxa) Musk Lorikeet Brown Goshawk Year-round, All Years Little Lorikeet Collared Sparrowhawk Date: Purple-crowned Lorikeet Black Kite Start Time: Whistling Kite Duration: Grouse, Quail, and Allies White-bellied Sea-Eagle Distance: Brown Quail Party Size: Stubble Quail Bee-eaters, Rollers, and Allies Rainbow Bee-eater Waterfowl Loons and Grebes Dollarbird Plumed Whistling-Duck Australasian Grebe Greylag Goose (Domestic type) Hoary-headed Grebe Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers Freckled Duck Great Crested Grebe Silver Gull Black Swan Gull-billed Tern Australian Shelduck Cormorants and Anhingas Caspian Tern Australian Wood Duck Little Pied Cormorant White-winged Black Tern Australasian Shoveler Great Cormorant Whiskered Tern Pacific Black Duck Little Black Cormorant Grey Teal Pied Cormorant Pigeons and Doves Chestnut Teal Australasian Darter Rock Dove Pink-eared Duck Spotted Dove Hardhead Pelicans Common Bronzewing Blue-billed Duck Australian Pelican Crested Pigeon Musk Duck Peaceful Dove Herons, Ibis, and Allies Shorebirds White-necked Heron Cuckoos Pied Stilt Great Egret Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Red-necked Avocet Intermediate Egret Black-eared Cuckoo Pacific Golden-Plover White-faced Heron Shining Bronze-Cuckoo Masked Lapwing Cattle