Arrival Dates of Migrant Bush Birds in the Strathalbyn District: a 45 Year Collaborative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report the Drongos Last Won the 30Hr Race Back in 2017 and It Was Great Getting That Team Back Together Again

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report The Drongos last won the 30hr race back in 2017 and it was great getting that team back together again. Maxie the Co-pilot and Simon ‘The Whisperer’ joined the Capt’n for a week of birding out west before heading to our starting point in the mulga. It is here I should mention that the area is currently seeing an absolute boom period after recent rains and was heaving with birds. So with this in mind and with our proven ‘golden route’ we were quite confident of scoring a reasonably good score. We awoke to rain on tin and it didn’t stop as we drove to the mulga, in fact it got heavier.As we sat in the car with 20min until start time we were contemplating if this would kill our run. But as we walked around in the drizzle we soon realised the birds were still active. Simon found a family of Inland Thornbill (a bird I always like to start with), Max had found a roosting Hobby and I’d found some Bee-eaters and Splendid Fairywrens. As the alarm chimed we quickly ticked up all those species as well as Red-capped Robin, Masked and White-browed Woodswallow, Black Honeyeater, White-winged Triller and Budgerigar. The Little Eagle was still on it’s nest and a pair of Plum-headed Finches shot past. We then changed location within the mulga and soon flushed a Little Buttonquail!! Common Bronewing, Owlet-nightjar and Mulga Parrot soon fell and after 20min we were off. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications Unit 2002 Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem Craig R. Allen U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Denis A. Saunders Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ncfwrustaff Part of the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Allen, Craig R. and Saunders, Denis A., "Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterraneanclimate Ecosystem" (2002). Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ncfwrustaff/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Cooperative Fish & Wildlife Research Unit -- Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Ecosystems (2002) 5: 348–359 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-001-0079-2 ECOSYSTEMS © 2002 Springer-Verlag Variability between Scales: Predictors of Nomadism in Birds of an Australian Mediterranean- climate Ecosystem Craig R. Allen1* and Denis A. Saunders2 1US Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, South Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, G27 Lehotsky, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634, USA; and 2CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, GPO Box 284, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia ABSTRACT Nomadism in animals is a response to resource dis- cance of the variables body mass and diet (nectar) tributions that are highly variable in time and space. may reflect the greater energy requirements of Using the avian fauna of the Mediterranean-climate large birds and the inherent variability of nectar as region of southcentral Australia, we tested a num- a food source. -

Brookfield CP Bird List

Bird list for BROOKFIELD CONSERVATION PARK -34.34837 °N 139.50173 °E 34°20’54” S 139°30’06” E 54 362200 6198200 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Rainbow Bee-eater Mulga Parrot Eastern Bluebonnet Red-rumped Parrot Australian Boobook *Feral Pigeon Common Bronzewing Crested Pigeon Australian Bustard Spur-winged Plover Little Buttonquail (Masked Lapwing) Painted Buttonquail Stubble Quail Cockatiel Mallee Ringneck Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Australian Ringneck) Little Corella Yellow Rosella Black-eared Cuckoo (Crimson Rosella) Fan-tailed Cuckoo Collared Sparrowhawk Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Grey Teal Pallid Cuckoo Shining Bronze Cuckoo Peaceful Dove Maned Duck Pacific Black Duck Little Eagle Wedge-tailed Eagle Emu Brown Falcon Peregrine Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Galah Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe Spotted Harrier White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Nankeen Kestrel Red-backed Kingfisher Black Kite Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite Laughing Kookaburra Banded Lapwing Musk Lorikeet Purple-crowned Lorikeet Malleefowl Spotted Nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Blue-winged Parrot Elegant Parrot If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. SEASONS – Spring: September, October, November; Summer: December, January, February; Autumn: March, April May; Winter: June, July, August IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ONLY BIRDS SEEN WITHIN THE RESERVE ARE RECORDED ON THIS LIST. -

2015 QUEENSLAND TWITCHATHON 18 - 28 September 2015

2015 QUEENSLAND TWITCHATHON 18 - 28 September 2015 IOC Alphabetical Checklist of the Birds of Queensland: Source http://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist. Team Name: Race Category: Total Number of Species: Photographic Category Only. Photos vetted by: Results (number of counted species) must be received by phone (0488 636 010) by 8pm Monday 28 September. Results (this list with counted species marked) must be received by email to [email protected] by 8pm Friday, 2 October. Column1 Column2 Column3 1 Albert's Lyrebird 2 Apostlebird 3 Arafura Fantail 4 Atherton Scrubwren 5 Australasian Bittern 6 Australasian Darter 7 Australasian Figbird 8 Australasian Gannet 9 Australasian Grebe 10 Australasian Shoveler 11 Australian Brushturkey 12 Australian Bustard 13 Australian Crake 14 Australian Golden Whistler 15 Australian Hobby 16 Australian King Parrot 17 Australian Logrunner 18 Australian Magpie 19 Australian Masked Owl 20 Australian Owlet-nightjar 21 Australian Painted-snipe 22 Australian Pelican 23 Australian Pied Cormorant 24 Australian Pipit 25 Australian Pratincole 26 Australian Raven 27 Australian Reed Warbler 28 Australian Ringneck 1/11 Column1 Column2 Column3 29 Australian Shelduck 30 Australian Swiftlet 31 Australian White Ibis 32 Azure Kingfisher 33 Baillon's Crake 34 Banded Honeyeater 35 Banded Lapwing 36 Banded Stilt 37 Banded Whiteface 38 Bar-breasted Honeyeater 39 Bar-shouldered Dove 40 Bar-tailed Godwit 41 Barking Owl 42 Barn Swallow 43 Barred Cuckooshrike 44 Bassian Thrush 45 Beach Stone-curlew 46 Bell Miner 47 Black Bittern -

Toorale National Park and Toorale State Conservation Area NSW Supplement Contents Key

BUSH BLITZ SPECIES DISCOVERY PROGRAM Toorale National Park and Toorale State Conservation Area NSW Supplement Contents Key Appendix A: Species Lists 3 * = New record for this reserve Fauna 4 ^ = Exotic/Pest Vertebrates 4 # = EPBC listed Mammals 4 ~ = TSC (NSW) listed Birds 5 † = FMA (NSW) listed Reptiles 8 ‡ = NCA (Qld) listed Frogs and Toads 9 Invertebrates 10 EPBC = Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) True Bugs — Aquatic 10 FMA = Fisheries Management Act 1994 Damselflies and Dragonflies 10 (New South Wales) Snails — Terrestrial 10 NCA = Nature Conservation Act 1992 Snails — Freshwater 10 (Queensland) Mussels 10 TSC = Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 Flora 11 (New South Wales) Flowering Plants 11 Colour coding for entries: Appendix B: Threatened Species 13 Black = Previously recorded on the reserve and Fauna 14 found on this survey Vertebrates 14 Brown = Putative new species Mammals 14 Blue = Previously recorded on the reserve but Birds 14 not found on this survey Frogs and Toads 14 Appendix C: Exotic and Pest Species 15 Fauna 16 Vertebrates 16 Mammals 16 Birds 16 Flora 17 Flowering Plants 17 2 Bushush BlitzBlitz surveysurvey reportreport — North-western NSW and southern Qld 2009–2010 Appendix A: Species Lists Nomenclature and taxonomy used in this appendix are consistent with that from the Australian Faunal Directory (AFD), the Australian Plant Name Index (APNI) and the Australian Plant Census (APC). Current at March 2014 Toorale National Park and Toorale State Conservation Area NSW Supplement 3 Fauna Vertebrates Mammals Family Species Common name Bovidae Bos taurus ^ * European Cattle Capra hircus ^ Goat Ovis aries ^ * Sheep Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox, Red Fox Dasyuridae Sminthopsis murina * Common Dunnart Emballonuridae Saccolaimus flaviventris ~ Yellow-bellied Sheathtail-bat Leporidae Lepus capensis ^ * Brown Hare Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ * Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus fuliginosus Western Grey Kangaroo Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropus rufus Red Kangaroo Molossidae Mormopterus sp. -

Coos, Booms, and Hoots: the Evolution of Closed-Mouth Vocal Behavior in Birds

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12988 Coos, booms, and hoots: The evolution of closed-mouth vocal behavior in birds Tobias Riede, 1,2 Chad M. Eliason, 3 Edward H. Miller, 4 Franz Goller, 5 and Julia A. Clarke 3 1Department of Physiology, Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas 78712 4Department of Biology, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador A1B 3X9, Canada 5Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 84112, Utah Received January 11, 2016 Accepted June 13, 2016 Most birds vocalize with an open beak, but vocalization with a closed beak into an inflating cavity occurs in territorial or courtship displays in disparate species throughout birds. Closed-mouth vocalizations generate resonance conditions that favor low-frequency sounds. By contrast, open-mouth vocalizations cover a wider frequency range. Here we describe closed-mouth vocalizations of birds from functional and morphological perspectives and assess the distribution of closed-mouth vocalizations in birds and related outgroups. Ancestral-state optimizations of body size and vocal behavior indicate that closed-mouth vocalizations are unlikely to be ancestral in birds and have evolved independently at least 16 times within Aves, predominantly in large-bodied lineages. Closed-mouth vocalizations are rare in the small-bodied passerines. In light of these results and body size trends in nonavian dinosaurs, we suggest that the capacity for closed-mouth vocalization was present in at least some extinct nonavian dinosaurs. As in birds, this behavior may have been limited to sexually selected vocal displays, and hence would have co-occurred with open-mouthed vocalizations. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

Native Animal Species List

Native animal species list Native animals in South Australia are categorised into one of four groups: • Unprotected • Exempt • Basic • Specialist. To find out the category your animal is in, please check the list below. However, Specialist animals are not listed. There are thousands of them, so we don’t carry a list. A Specialist animal is simply any native animal not listed in this document. Mammals Common name Zoological name Species code Category Dunnart Fat-tailed dunnart Sminthopsis crassicaudata A01072 Basic Dingo Wild dog Canis familiaris Not applicable Unprotected Gliders Squirrel glider Petaurus norfolcensis E04226 Basic Sugar glider Petaurus breviceps E01138 Basic Possum Common brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula K01113 Basic Potoroo and bettongs Brush-tailed bettong (Woylie) Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi M21002 Basic Long-nosed potoroo Potorous tridactylus Z01175 Basic Rufous bettong Aepyprymnus rufescens W01187 Basic Rodents Mitchell's hopping-mouse Notomys mitchellii Y01480 Basic Plains mouse (Rat) Pseudomys australis S01469 Basic Spinifex hopping-mouse Notomys alexis K01481 Exempt Wallabies Parma wallaby Macropus parma K01245 Basic Red-necked pademelon Thylogale thetis Y01236 Basic Red-necked wallaby Macropus rufogriseus K01261 Basic Swamp wallaby Wallabia bicolor E01242 Basic Tammar wallaby Macropus eugenii eugenii C05889 Basic Tasmanian pademelon Thylogale billardierii G01235 Basic 1 Amphibians Common name Zoological name Species code Category Southern bell frog Litoria raniformis G03207 Basic Smooth frog Geocrinia laevis -

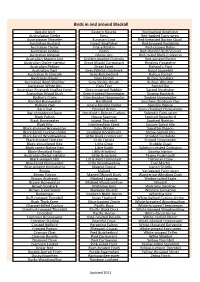

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Threatened and Declining Birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: Ii

THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Patchy but non-random distribution of remnant vegetation in the South West Slopes, NSW JULIAN R.W. REID CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] NOVEMBER 2000 Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships A consultancy report prepared for the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service with Threatened Species Unit (now Biodiversity Management Unit) funding. ii THREATENED AND DECLINING BIRDS IN THE NEW SOUTH WALES SHEEP-WHEAT BELT: II. LANDSCAPE RELATIONSHIPS – MODELLING BIRD ATLAS DATA AGAINST VEGETATION COVER Julian R.W. Reid November 2000 CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Project Manager: Sue V. Briggs, NSW NPWS Address: C/- CSIRO, GPO Box 284, Canberra 2601; [email protected] Disclaimer: The contents of this report do not necessarily represent the official views or policy of the NSW Government, the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, or any other agency or organisation. Citation: Reid, J.R.W. 2000. Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape relationships – modelling bird atlas data against vegetation cover. Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Consultancy report to NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra. ii Declining Birds in the NSW Sheep-Wheat Belt: II. Landscape Relationships Threatened and declining birds in the New South Wales Sheep-Wheat Belt: II.