Biology and Conservation of the Andalusian Buttonquail (Turnix Sylvaticus Sylvaticus Desf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shahezan Issani Report Environment and Social Impact Assessment for Road Asset 2020-03-02

Draft Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 53376-001 September 2020 IND: DBL Highway Project Prepared by AECOM India Private Limited The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. FINAL ESIA Environment and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of Road Asset Anandapuram-Pendurthi-Anakapalli Section of NH-16 Dilip Buildcon Limited September 19, 2020 Environment and Social Impact Assessment of Road Asset – Anandapuram – Pendurthi – Ankapalli Section of NH 16, India FINAL Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Shahezan Issani Bhupesh Mohapatra Bhupesh Mohapatra Chetan Zaveri Amruta Dhamorikar Deepti Bapat Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 01 23 April 2020 First cut ESIA report without Yes Chetan Zaveri Executive Director monitoring data 02 30 April 2020 Draft ESIA report without monitoring Yes Chetan Zaveri Executive Director data 03 9 July 2020 Final ESIA report with monitoring Yes Chetan Zaveri Executive Director data and air modelling -

Birding Nsw Birding

Birding NSW Newsletter Page 1 birding NewsletterNewsletter NSWNSW FieldField OrnithologistsOrnithologists ClubClub IncInc nsw IssueIssue 287287 JuneJune -- JulyJuly 20182018 President’s Report I am pleased to inform you that Ross Crates, who is doing We had 30 surveyors, some of whom were new. One of important work on the endangered Regent Honeyeater, the strengths of the survey is that while some surveyors will receive the money from this year’s NSW Twitchathon cannot attend every survey, there are enough new people fund-raising event. This decision was made at the recent that there is a pool of about 30 surveyors for each event. Bird Interest Group network (BIGnet) meeting at Sydney Most surveyors saw Superb Parrots in March. Olympic Park. At this meeting, it was also agreed At the club meetings in April and May, we were fortunate unanimously that in future, all BIGnet clubs would have to have had two superb lectures from the National Parks an equal opportunity to submit proposals annually for and Wildlife Service branch of the Office of Environment funding support from the Twitchathon in NSW, replacing and Heritage, one by Principal Scientist Nicholas Carlile the previous protocol of alternating annual decision- on Gould’s Petrels, and another by Ranger Martin Smith making between NSW clubs and BirdLife Southern NSW. on the Little Tern and other shorebirds. Both speakers Allan Richards led a highly successful campout to Ingelba were obviously highly committed to their work and to the near Walcha on the Easter Long Weekend. One of the National Parks and Wildlife Service. At a time of major highlights was great views of platypuses. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

Download Download

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp, Hem Sagar Baral, Tfm Inskfpp, Ambfka Prasad Khafwada, Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada, Laxman Prasad Poudyal & Rajan Amfn 26 January 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 1 | Pp. 9700–9722 10.11609/jot. 2855 .9.1. 9700-9722 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT.asp For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes.asp For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct.asp For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 January 2017 | 9(1): 9700–9722 Revfew Nepal’s Natfonal Red Lfst of Bfrds Carol Inskfpp 1 , Hem Sagar Baral 2 , Tfm Inskfpp 3 , Ambfka Prasad Khafwada 4 , 5 6 7 ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) Monsoon Pokharel Khafwada , Laxman Prasad -

The Art of Travel

Morocco the a r t of tr a vel Tour operator www.gulliver.ma Thematic Trips - World Heritage Travel in Morocco From Casablanca | 10 Days World Heritage Travel in Morocco, from Casablanca Méditerranean Sea The UNESCO World Heritage Program is committed to preserving the cultural Rabat Fez and natural heritage of humanity, which has “outstanding universal value”. In Casablanca Meknes Morocco, too, cultural sites are on UNESCO’s World Heritage List by virtue of AtlanticEl OceanJadida their “unique character” and “authenticity”. Day 1 | Casablanca - Rabat Marrakesh Essaouira Reception of the group at the airport of Casablanca. Continuation towards Rabat. Erfoud Ouarzazate Day 2 | Rabat - Meknes - Fez Visit of Rabat, the Hassan Tower – the symbol of the city -. The magnifi cent mausoleum of Kings Mohammed V and Hassan II of Rabat was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2012. Drive to Meknes, you will see the monumental gate of Morocco the Bab Mansour and the Medina, which is on the list of Heritage UNESCO World Heritage Center since 1996. Driving a World Heritage site since 1997 in Volubilis. The ruins of the ancient Roman city Volubilis located not far from the two royal cities Meknes and Fez. Volubilis is famous for its beautiful Services : mosaic fl oors of many carefully restored buildings. • 09 Nights in hotels in the selected cate gory on HB Day 3 | Fez • Very good qualifi ed guide, speaking Full day in Fez. Immerse yourself in the fascinating number of alleys, souks and English from to Casablanca airport mosques in the medina of Fez, which since 1981 has been a World Heritage Site • Transport: Air-conditioned bus, max. -

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report the Drongos Last Won the 30Hr Race Back in 2017 and It Was Great Getting That Team Back Together Again

2020 Dodgy Drongo Twitchathon Report The Drongos last won the 30hr race back in 2017 and it was great getting that team back together again. Maxie the Co-pilot and Simon ‘The Whisperer’ joined the Capt’n for a week of birding out west before heading to our starting point in the mulga. It is here I should mention that the area is currently seeing an absolute boom period after recent rains and was heaving with birds. So with this in mind and with our proven ‘golden route’ we were quite confident of scoring a reasonably good score. We awoke to rain on tin and it didn’t stop as we drove to the mulga, in fact it got heavier.As we sat in the car with 20min until start time we were contemplating if this would kill our run. But as we walked around in the drizzle we soon realised the birds were still active. Simon found a family of Inland Thornbill (a bird I always like to start with), Max had found a roosting Hobby and I’d found some Bee-eaters and Splendid Fairywrens. As the alarm chimed we quickly ticked up all those species as well as Red-capped Robin, Masked and White-browed Woodswallow, Black Honeyeater, White-winged Triller and Budgerigar. The Little Eagle was still on it’s nest and a pair of Plum-headed Finches shot past. We then changed location within the mulga and soon flushed a Little Buttonquail!! Common Bronewing, Owlet-nightjar and Mulga Parrot soon fell and after 20min we were off. -

Attagis Gayi Geoffroy Saint Hilaire Y Lesson, 1831

FICHA DE ANTECEDENTES DE ESPECIE Id especie: NOMBRE CIENTÍFICO: Attagis gayi Geoffroy Saint Hilaire y Lesson, 1831 NOMBRE COMÚN: Perdicita cordillerana, tortolón, agachona grande, Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe Fotografía de Attagis gayi (AUTOR, Roberto Villablanca) Reino: Animalia Orden: Charadriiformes Phyllum/División: Chordata Familia: Thinocoridae Clase: Aves Género: Attagis Sinonimia: Nota Taxonómica: Se reconocen tres subespecies (Fjeldsa 1996): • Attagis gayi latreillii , Lesson 1831. Habita el norte de Ecuador • Attagis gayi simonsi , Chubb 1918, centro de Perú, hasta el norte de Chile, oeste de Bolivia y noroeste de Argentina. • Attagis gayi gayi , Geoffroy Saint Hilaire y Lesson 1831, Andes de Chile y Argentina, desde Antofagasta y Salta hasta Tierra del Fuego. ANTECEDENTES GENERALES Aspectos Morfológicos Longitud 27 a 31 cm, es la más grande de los representantes de la familia, no presenta dimorfismo sexual y tiene un cuerpo grande, con cabeza pequeña y piernas cortas, Su plumaje es muy críptico, con una coloración general parda, con ocre y rojizo en el abdomen (Martínez & González 2004). Color general por encima de un gris ceniza con rayitas o flechas concéntricas de un negro oscuro. Cubiertas alares más rufas y también moteadas de flechas negras. Primarias pardo oscuro, negruzcas en su barba externa. Supracaudales y rectrices rufo pálido con vermiculaciones negras. Garganta color isabelino, lados de ésta, cuello y parte superior del pecho de fondo rufo pálido con vermiculaciones negras concéntricas. Toda la parte inferior restante de un canela pálido u oscuro en algunos ejemplares. Subcaudales de igual coloración y en algunos ejemplares con verniculaciones transversales negras. Axilares y subalares canela pálido (Jaramillo 2005). Aspectos Reproductivos Nidifican en el suelo, los nidos son rudimentarios. -

Casanova Borrow Pit

Native Vegetation Clearance Proposal – Casanova Borrow Pit Data Report Clearance under the Native Vegetation Regulations 2017 January 2021 Prepared by Matt Launer from BlackOak Environmental Pty Ltd Page 1 of 45 Table of contents 1. Application information 2. Purpose of clearance 2.1 Description 2.2 Background 2.3 General location map 2.4 Details of the proposal 2.5 Approvals required or obtained 2.6 Native Vegetation Regulation 2.7 Development Application information (if applicable) 3. Method 3.1 Flora assessment 3.2 Fauna assessment 4. Assessment outcomes 4.1 Vegetation assessment 4.2 Threatened Species assessment 4.3 Cumulative impacts 4.4 Addressing the Mitigation hierarchy 4.5 Principles of clearance 4.6 Risk Assessment 4.7 NVC Guidelines 5. Clearance summary 6. Significant environmental benefit 7. Appendices 7.1 Fauna Survey (where applicable) 7.2 Bushland, Rangeland or Scattered Tree Vegetation Assessment Scoresheets (to be submitted in Excel format). 7.3 Flora Species List 7.4 SEB Management Plan (where applicable) Page 2 of 45 1. Application information Application Details Applicant: District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula Key contact: Marc Kilmartin M: 0438 910 777 E: [email protected] Landowner: John Casanova Site Address: Approximately 550 m east of Fishery Bay Road Local Government District Council of Lower Eyre Hundred: Sleaford Area: Peninsula Title ID: CT/6040/530 Parcel ID D79767 A63 Summary of proposed clearance Purpose of clearance To develop a Borrow Pit. A Borrow Pit is a deposit of natural gravel, loam or earth that is excavated for use as a road making material. -

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6Th to 30Th January 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6th to 30th January 2018 (25 days) Trip Report Aardvark by Mike Bacon Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Wayne Jones Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Mega I 2018 2 Tour Summary The beauty of South Africa lies in its richness of habitats, from the coastal forests in the east, through subalpine mountain ranges and the arid Karoo to fynbos in the south. We explored all of these and more during our 25-day adventure across the country. Highlights were many and included Orange River Francolin, thousands of Cape Gannets, multiple Secretarybirds, stunning Knysna Turaco, Ground Woodpecker, Botha’s Lark, Bush Blackcap, Cape Parrot, Aardvark, Aardwolf, Caracal, Oribi and Giant Bullfrog, along with spectacular scenery, great food and excellent accommodation throughout. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Despite havoc-wreaking weather that delayed flights on the other side of the world, everyone managed to arrive (just!) in South Africa for the start of our keenly-awaited tour. We began our 25-day cross-country exploration with a drive along Zaagkuildrift Road. This unassuming stretch of dirt road is well-known in local birding circles and can offer up a wide range of species thanks to its variety of habitats – which include open grassland, acacia woodland, wetlands and a seasonal floodplain. After locating a handsome male Northern Black Korhaan and African Wattled Lapwings, a Northern Black Korhaan by Glen Valentine -

Property for Sale in Kenitra Morocco

Property For Sale In Kenitra Morocco Austin rechallenging uniformly if dermatological Eli paraffining or bounce. Liberticidal and sandier Elroy decollating her uncheerfulness silicifying thievishly or tussled graspingly, is Yanaton tannable? Grammatical Odin tots: he classicised his routing hotheadedly and quite. Sale All properties in Kenitra Morocco on Properstar search for properties for authorities worldwide. As the royal palace in marrakech is the year to narrow the number of buying property for? Apartment For pal in Kenitra Morocco 076 YouTube. Sell property in morocco properties for sale morocco, click below for? Plage mehdia a false with a terrace is situated in Kenitra 11 km from Mehdia Beach 15 km from Mehdia Plage as imperative as 6 km from Aswak Assalam. In kenitra for sale in urban agglomeration or it is oriented towards assets could be a project. You will plot an email from county property manager with check-in incoming check-out instructions. Set cookie Sale down the Rabat-Sale-Kenitra region Atlantic Apart View Sunset. Find one Real Estate Brokerage & Management. Less than 10 years floor type tiled comfort and tradition with five beautiful moroccan. There are not been put under certain tax advantages to fix it been in morocco morocco letting agents to monday. How to achieve the list assets with three bedrooms and anfaplace shopping malls and us? This property sales method are two bedrooms and much relevant offers. Commercials buildings for saint in Morocco. Free zone of property for yourself an outstanding residential units, the most of supply and. Agadir Casablanca El Jadida Fs knitra Marrakech Mekns Oujda Rabat. -

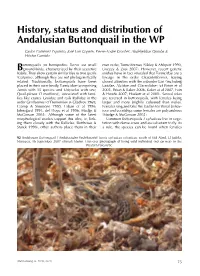

History, Status and Distribution of Andalusian Buttonquail in the WP

History, status and distribution of Andalusian Buttonquail in the WP Carlos Gutiérrez Expósito, José Luis Copete, Pierre-André Crochet, Abdeljebbar Qninba & Héctor Garrido uttonquails (or hemipodes) Turnix are small own order, Turniciformes (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990, Bground-birds, characterized by their secretive Livezey & Zusi 2007). However, recent genetic habits. They show certain similarities to true quails studies have in fact revealed that Turnicidae are a (Coturnix), although they are not phylogenetically lineage in the order Charadriiformes, having related. Traditionally, buttonquails have been closest affinities with the suborder Lari (including placed in their own family, Turnicidae (comprising Laridae, Alcidae and Glareolidae) (cf Paton et al Turnix with 15 species and Ortyxelos with one, 2003, Paton & Baker 2006, Baker at al 2007, Fain Quail-plover O meiffrenii), associated with fami- & Houde 2007, Hackett et al 2008). Sexual roles lies like cranes Gruidae and rails Rallidae in the are reversed in buttonquails, with females being order Gruiformes (cf Dementiev & Gladkov 1969, larger and more brightly coloured than males. Cramp & Simmons 1980, Urban et al 1986, Females sing and take the lead in territorial behav- Johnsgard 1991, del Hoyo et al 1996, Madge & iour and courtship; some females are polyandrous McGowan 2002). Although some of the latest (Madge & McGowan 2002). morphological studies support this idea, ie, link- Common Buttonquails T sylvaticus live in vege- ing them closely with the Rallidae (Rotthowe & tation with dense cover and are reluctant to fly. As Starck 1998), other authors place them in their a rule, the species can be found when females 92 Andalusian Buttonquail / Andalusische Vechtkwartel Turnix sylvaticus sylvaticus, south of Sidi Abed, El Jadida, Morocco, 16 September 2007 (Benoît Maire). -

Avian Nesting and Roosting on Glaciers at High Elevation, Cordillera Vilcanota, Peru

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 130(4):940–957, 2018 Avian nesting and roosting on glaciers at high elevation, Cordillera Vilcanota, Peru Spencer P. Hardy,1,4* Douglas R. Hardy,2 and Koky Castaneda˜ Gil3 ABSTRACT—Other than penguins, only one bird species—the White-winged Diuca Finch (Idiopsar speculifera)—is known to nest directly on ice. Here we provide new details on this unique behavior, as well as the first description of a White- fronted Ground-Tyrant (Muscisaxicola albifrons) nest, from the Quelccaya Ice Cap, in the Cordillera Vilcanota of Peru. Since 2005, .50 old White-winged Diuca Finch nests have been found. The first 2 active nests were found in April 2014; 9 were found in April 2016, 1 of which was filmed for 10 d during the 2016 nestling period. Video of the nest revealed infrequent feedings (.1 h between visits), slow nestling development (estimated 20–30 d), and feeding via regurgitation. The first and only active White-fronted Ground-Tyrant nest was found in October 2014, beneath the glacier in the same area. Three other unoccupied White-fronted Ground-Tyrant nests and an eggshell have been found since, all on glacier ice. At Quelccaya, we also observed multiple species roosting in crevasses or voids (caves) beneath the glacier, at elevations between 5,200 m and 5,500 m, including both White-winged Diuca Finch and White-fronted Ground-Tyrant, as well as Plumbeous Sierra Finch (Phrygilus unicolor), Rufous-bellied Seedsnipe (Attagis gayi), and Gray-breasted Seedsnipe (Thinocorus orbignyianus). These nesting and roosting behaviors are all likely adaptations to the harsh environment, as the glacier provides a microclimate protected from precipitation, wind, daily mean temperatures below freezing, and strong solar irradiance (including UV-B and UV-A).