Saussure's Value(S)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GIPE-011123-Contents.Pdf (1.391Mb)

THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT The .Riiyal I ...tiIIute oj Intemalional Affairs i8 _ ..""jftcial tJnrl """.po!ilicaZ body,Joon.dtd ... 1920 to .....",..,.ag. tJnrl Jat>iZital. Ike 8cientific 8ttu% oj intemalionaZ qu<8t1of18. The 11l81i1ut., ... BUCh, i8 precluded by;u rvlu from upruring an opinion 011 any CUlpect oJ...,.,.• ....eionaZ "ffaVr8; opinionB upru.ed ... 1MB book or.. /hereJor., pur'11I indWiduoZ. THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL • INVESTMENT . A Report by a Study Group of Members of the Royal Institute of International Mairs OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO 1 __ -urIM .....,.;_ ~IM R'¥IlI"- ~I-.. ..... -'~ 1937 ODORD UNIVERSITY PRBSS AMBN ROUBH, B.C. 4 London Bdlnbmgb Glalgow New York 'l'OlOIlto Melbourne Capetown Bomb., Calcutta Madru HUIIPHREY IIILII'ORD PVBLIBBBB W nm VIn'D8lfl' XbSZ;-. \.N3t &7 /1 ( 2.. J FOREWORD TIm Council of the Royal Institute of International Affairs believe that this a.ddition to the series of Study Group Reports will fill an important gap in the literature of international economics. It is an attempt, in the first ple.ce, to e.na.lyse objectively the conditions under which long-term oapital may move between countries and to consider oe.refully the speoie.l fe.otors in the world economy of to-day which tend to limit the extent to which such movements e.re possible or desirable. Secondly, the book contains a careful study of the post war history of international investments which brings together facts and figures whioh e.re ine.ocessible to most students and business men. The Council is indebted to the following group of members of the Institute for the preparation of the Report: Mr. -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M. AT Edithvale Community Centre, 7 Edithvale Drive, North York MAIL ADDRESS: NORTH YORK COIN CLUB, P.O.BOX 10005 R.P.O. Yonge & Finch, 5576 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario, M2N 0B6 Web site: www.northyorkcoinclub.ca Contact the Club : Executive Committee E-mail: [email protected] President ........................................Nick Cowan Director ..........................................David Quinlan Receptionist ................................Franco Farronato Phone: 647-222-9995 1st Vice President ..........................Bill O’Brien Director ..........................................Roger Fox Draw Prizes..................................Bill O’Brien 2nd Vice President..........................Shawn Hamilton Director ..........................................Vince Chiappino Social Convenor ..........................Bill O’Brien Member : Secretary ........................................Henry Nienhuis Junior Director ................................ Librarian ......................................Robert Wilson Program Planning ........................ Canadian Numismatic Assocation Treasurer ........................................ Auctioneer ......................................Bob Porter Past President ................................Robert Wilson Auction Manager ............................Mark Argentino Ontario Numismatic Association Editor ..............................................Paul Petch THE BULLETIN FOR APRIL 2009 Regular club members -

The Big Reset: War on Gold and the Financial Endgame

WILL s A system reset seems imminent. The world’s finan- cial system will need to find a new anchor before the year 2020. Since the beginning of the credit s crisis, the US realized the dollar will lose its role em as the world’s reserve currency, and has been planning for a monetary reset. According to Willem Middelkoop, this reset MIDD Willem will be designed to keep the US in the driver’s seat, allowing the new monetary system to include significant roles for other currencies such as the euro and China’s renminbi. s Middelkoop PREPARE FOR THE COMING RESET E In all likelihood gold will be re-introduced as one of the pillars LKOOP of this next phase in the global financial system. The predic- s tion is that gold could be revalued at $ 7,000 per troy ounce. By looking past the American ‘smokescreen’ surrounding gold TWarh on Golde and the dollar long ago, China and Russia have been accumu- lating massive amounts of gold reserves, positioning them- THE selves for a more prominent role in the future to come. The and the reset will come as a shock to many. The Big Reset will help everyone who wants to be fully prepared. Financial illem Middelkoop (1962) is founder of the Commodity BIG Endgame Discovery Fund and a bestsell- s ing author, who has been writing about the world’s financial system since the early 2000s. Between 2001 W RESET and 2008 he was a market commentator for RTL Television in the Netherlands and also BIG appeared on CNBC. -

3Ffq Vdk Hf"*'Ll-,Tr E{-.-,Drri.Ld L2/11-130

tso/rEc JTc l/sc 2JING2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from htip:/lwww.dkuuq.dklJTCllSC2lWG2ldocslprirrcirrtes.htryl- for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http:/lwww.dkuuq.dkJJTCllSC2lWG2ldcc-slsuqfigfflgjli11id. See also httn./lwww.dku 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: (or) More information will be provided later: B. Technical - General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): ,<1 t:A Proposed name of script: -----------_/:_ b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: YPq Name of the existing btock: -_-C-UfU*n<_:4 -5-.1-,rrh-ol,S- _-____--- __--f-":"-____--___ 2.Numberofcharactersinproposal: I | --L- -----_ 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary --\_ B.1-specialized (smallcollection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct _____ D-Attested extinct E-Minor e)dinctextinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or ldeographi G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. ls a repertoire including character names provided? _-y_t_l-_-__ _ _ -_ a. lf YES, are the names in accordance with the "character naming guidelines" t in Annex L of P&P document? __y_t--t-___-_____-_ b. Are the character shapes attached in a legible form suitable for review? llgS-" - 5. -

Eelu United States Attorneys

Published by Executive Office for United States Attorneys Department of Justice Washirgton July 1954 EELU JULl2lBb4 TTOREY M4GELES ChUF United tates 1.05 DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Vol No 14 UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS BULLETIN of RESTRICTED TO USEOF DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE PERSONNEL UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS BULLETIN ____ VOL July l95Il No RESPONSE TO NEW FORM Response of the United States Attorneys to the request for their views on the new proposed standardized fcm for transfers under Rule 20 has been most gratifying Not only have the replies been prompt but from the recommendations and suggestions contained therein it is quite apparent that the format and content of the form were very carefully studied review of these suggestions is now being made and it is contemplated that the form will be readr or general diatri bution in the near future JOB WELL DONE James Beary Special Agent in Charge of the United States Secret Service Washington has written United States Attorney Leo Rover of the District of Columbia expressing his appreciation for the excellent advice received from Assistant United States Attorney Riley Casey during the preparation of the Landis case set out in the Criminal Division section of this Bulletin and throughout the entire jicial procedure as well as for the assistance and cooperation Mr Casey gave the Secret Service during their investigation Mr Beary stated that great share of the credit should go to Mr Casey for the expeditious handling of the case before the Courts and for the fact that an expensive trial was unnecessary. -

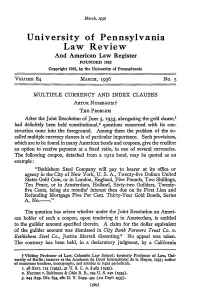

Multiple Currency and Index Clauses

March, r936 University of Pennsylvania Law Review And American Law Register FOUNDED 1852 Copyright 1936, by the University of Pennsylvania VOLUME 84 MARCH, 1936 No. 5 MULTIPLE CURRENCY AND INDEX CLAUSES ARTUR NUSSBAUMf THE PROBLEM After the Joint Resolution of June 5, 1933, abrogating the gold clause,' had definitely been held constitutional, 2 questions concerned with its con- struction came into the foreground. Among them the problem of the so- called multiple currency clauses is of particular importance. Such provisions, which are to be found in many American bonds and coupons, give the creditor an option to receive payment at a fixed ratio, in one of several currencies. The following coupon, detached from a 1912 bond, may be quoted as an example: "Bethlehem Steel Company will pay to bearer at its office or agency in the City of New York, U. S. A., Twenty-five Dollars United States Gold Coin, or in London, England, Five Pounds, Two Shillings, Ten Pence, or in Amsterdam, Holland, Sixty-two Guilders, Twenty- five Cents, being six months' interest then due on its First Lien and Refunding Mortgage Five Per Cent. Thirty-Year Gold Bonds, Series A, No.-." The question has arisen whether under the Joint Resolution an Ameri- can holder of such a coupon, upon tendering it in Amsterdam, is entitled to the guilder amount specified therein. A claim for the dollar equivalent of the guilder amount was dismissed in City Bank Farmers Trust Co. v. Bethlehem Steel Co., Justice Merrell dissenting.3 No appeal was taken. The contrary has been held, in a declaratory judgment, by a California t Visiting Professor of Law, Columbia Law School; formerly Professor of Law, Uni- versity of Berlin; lecturer at the Academie du Droit International de la Hague, i933; author of numerous treatises, monographs, and articles in legal periodicals. -

Volume VI — Reports of International Arbitral Awards

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES VOLUME VI United Nations Publication Sales No. : 1955. V. 3 Price: $U.S. 4.00; 28/- stg. ; Sw. fr. 17.00 (or equivalent in other currencies) REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES VOLUME VI Decisions of Arbitral Tribunal GREAT BRITAIN-UNITED STATES and of Claims Commissions UNITED STATES, AUSTRIA AND HUNGARY and UNITED STATES-PANAMA Décisions du Tribunal arbitral GRANDE-BRETAGNE - ETATS-UNIS et des Commissions de réclamations ETATS-UNIS, AUTRICHE ET HONGRIE et ETATS-UNIS - PANAMA UNITED NATIONS — NATIONS UNIES FOREWORD The systematic collection of decisions of international claims commis- sions contemplated in the foreword to volume IV of the present series of Reports of International Arbitral Awards and already embracing the decisions of the so-called Mexican Claims Commissions, as far as available (vol. IV: General and Special Claims Commissions Mexico-United States; vol. V: Claims Commissions Great Britain-Mexico, France- Mexico and Germany-Mexico), is continued with the present volume devoted to the decisions of the Arbitral Tribunal United States-Great Britain constituted under the Special Agreement of August 18, 1910, the Tripartite Claims Commission United States. Austria and Hungary constituted under the Agreement of November 26, 1924, and the General Claims Commission United States-Panama constituted under the Claims Convention of July 28, 1926, modified by the Convention of December 17, 1932. The mode of presentation followed in this volume is the same as that used in volumes IV-V. Each award is captioned under the name of the individual claimant, together with identification of the espousing and the respondent governments. -

Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust

This page intentionally left blank P1: FpQ CY257/Brustein-FM 0 52177308 3 July 1, 2003 5:15 Roots of Hate On the eve of the Holocaust, antipathy toward Europe’s Jews reached epidemic proportions. Jews fleeing Nazi Germany’s increasingly anti- Semitic measures encountered closed doors everywhere they turned. Why had enmity toward European Jewry reached such extreme heights? How did the levels of anti-Semitism in the 1930s compare to those of earlier decades? Did anti-Semitism vary in content and intensity across societies? For example, were Germans more anti-Semitic than their European neighbors, and, if so, why? How does anti-Semitism differ from other forms of religious, racial, and ethnic prejudice? In pursuit of answers to these questions, William I. Brustein offers the first truly systematic comparative and empirical examination of anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust. Brustein proposes that European anti-Semitism flowed from religious, racial, economic, and po- litical roots, which became enflamed by economic distress, rising Jewish immigration, and socialist success. To support his arguments, Brustein draws upon a careful and extensive examination of the annual volumes of the American Jewish Year Book and more than forty years of newspaper reportage from Europe’s major dailies. The findings of this informative book offer a fresh perspective on the roots of society’s longest hatred. William I. Brustein is Professor of Sociology, Political Science, and His- tory and the director of the University Center for International Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. His previous books include The Logic of Evil (1996) and The Social Origins of Political Regionalism (1988). -

The Future of Gold from 2019 to 2039

The Future of Gold from 2019 to 2039 Sam Laakso Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in Business Administration 2019 Abstract 30.4.2019 Author(s) Sam Laakso Degree programme Finance and Economics Report/Thesis title Number of pages The Future of Gold from 2019 to 2039 and appendix pages 166 + 6 This report is an extensive gold market analysis which examines the future of the gold mar- ket starting from 2019 and ending to 2039. For the purpose of this report, seven interna- tionally recognised professionals including Gary Savage, Alexis Stenfors, James Rogers, David Brady, Brent Johnson, David Morgan and Jan Von Gerich were interviewed and over one hundred independent sources were examined. Aspects discussed in this report include gold’s monetary history over the past 150 years, the world’s current monetary system, the supply and demand factors of the gold market as well as the structure of the gold market itself, financial market manipulation and market effi- ciency, cycles analysis as well as the geopolitics around gold. The report examines all of these subjects individually after which these aspects are used to form a reliable and thor- ough market analysis. The report divides into two core segments which are the theoretical framework and the market analysis. The theoretical framework provides the foundation to which the market analysis is built on. The market analysis consists of three scenarios of which the first sce- nario examines purely the supply and demand fundamentals of the gold market, the sec- ond scenario presents a cycles analysis for gold and the thirds scenario examines the pos- sibility of a global monetary system reform. -

Administrative Decision No. II

REPORTS OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL AWARDS RECUEIL DES SENTENCES ARBITRALES Administrative Decision No. II 25 May 1927 VOLUME VI pp. 212-230 NATIONS UNIES - UNITED NATIONS Copyright (c) 2006 212 UNITED STATES, AUSTRIA AND HUNGARY 1926, adopted as between themselves a division of liabilities in harmony with the rule here announced. While this decision, in so far as applicable, will control the preparation, presentation, and decision of all claims submitted to the Commission falling within its scope, nevertheless should the American Agent, the Austrian Agent, and/or the Hungarian Agent be of the opinion that the peculiar facts of any case take it out of the rules here announced such facts with the differentiation believed to exist will be called to the attention of the Commissioner in the presentation of that case. ADMINISTRATIVE DECISION No. II (May 25, 1927. Pages 15-36.) INTERPRETATION OF TREATY: INDIRECT CONSEQUENCES OF CARRYING INTO EFFECT OF TREATY PROVISIONS. According to Trea ty of S t. Germain (Trianon), part X. section IV, annex, paragraph 14, "in the settlement of matters provided for in article 249 (232) . the provisions of section III respecting the currency in which payment is to be made and the rate of exchange and of interest" shall apply. Held that not all of the indirect consequences flowing from the carrying into effect of article 249 (232) are "matters provided for" therein. Enumeration of such matters. INTERPRETATION OF TREATY.—DEBTS, MEANING OF TERM IN TREATIES OF ST. GERMAIN (TRIANON), ART. 249 (232), (h) (2), AND VIENNA (BUDAPEST). Held that term "debt" in Treaty of St. -

Annual Report 2012

CGD REPORTS ANNUAL REPORT 2012 www.cgd.pt CaixaCaixa Geral Geral de de Depósitos, Depósitos, S.A. S.A. x •Sede Registered Social: Office:Av. João Av. XXI, João 63 XXI, – 1000-300 63 – 1000-300 Lisboa Lisbon Share capital EUR 5 900 000 000 • CRCL and tax no.500 960 046 Capital Social EUR 5 150 000 000 x CRCL e Contribuinte sob o n.º 500 960 046 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 CGD [THIS PAGE HAS BEEN INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ] CGD REPORTS CGD ANNUAL REPORT 2012 3 INDEX 1. BOARD OF DIRECTORS' REPORT ................................................................................ 9 1.1. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND CHAIRMAN OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE ......................................................... 9 1.2. MAIN INDICATORS ...................................................................................................... 11 1.3. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................. 12 1.4. GROUP PRESENTATION............................................................................................ 14 1.4.1. Equity Structure ............................................................................................ 14 1.4.2. Milestones ..................................................................................................... 14 1.4.3. Dimension and ranking of Group .................................................................. 16 1.4.4. CGD Group structure - recent developments ............................................... 18 1.4.5. Branch