Evolution and Intelligent Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uniqueness and Symmetry in Bargaining Theories of Justice

Philos Stud DOI 10.1007/s11098-013-0121-y Uniqueness and symmetry in bargaining theories of justice John Thrasher Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013 Abstract For contractarians, justice is the result of a rational bargain. The goal is to show that the rules of justice are consistent with rationality. The two most important bargaining theories of justice are David Gauthier’s and those that use the Nash’s bargaining solution. I argue that both of these approaches are fatally undermined by their reliance on a symmetry condition. Symmetry is a substantive constraint, not an implication of rationality. I argue that using symmetry to generate uniqueness undermines the goal of bargaining theories of justice. Keywords David Gauthier Á John Nash Á John Harsanyi Á Thomas Schelling Á Bargaining Á Symmetry Throughout the last century and into this one, many philosophers modeled justice as a bargaining problem between rational agents. Even those who did not explicitly use a bargaining problem as their model, most notably Rawls, incorporated many of the concepts and techniques from bargaining theories into their understanding of what a theory of justice should look like. This allowed them to use the powerful tools of game theory to justify their various theories of distributive justice. The debates between partisans of different theories of distributive justice has tended to be over the respective benefits of each particular bargaining solution and whether or not the solution to the bargaining problem matches our pre-theoretical intuitions about justice. There is, however, a more serious problem that has effectively been ignored since economists originally J. -

Slope Takers in Anonymous Markets"

Slope Takers in Anonymous Markets Marek Weretka,y 29th May 2011 Abstract In this paper, we study interactions among large agents trading in anonymous markets. In such markets, traders have no information about other traders’payo¤s, identities or even submitted orders. To trade optimally, each trader estimates his own price impact from the available data on past prices as well as his own trades and acts optimally, given such a simple (residual supply) representation of the residual mar- ket. We show that in a Walrasian auction, which is known to have a multiplicity of Nash equilibria that if all traders independently estimate and re-estimate price im- pacts, market interactions converge to a particular Nash equilibrium. Consequently, anonymity and learning argument jointly provide a natural selection argument for the Nash equilibrium in a Walrasian auction. We then study the properties of such focal equilibrium. JEL clasi…cation: D43, D52, L13, L14 Keywords: Walrasian Auction, Anonymous Thin Markets, Price impacts 1 Introduction Many markets, e.g., markets for …nancial assets are anonymous. In such markets inform- ation of each individual trader is restricted to own trades and commonly observed market price. Traders have no information about other traders’payo¤s, identities or submitted or- ders. The archetypical framework to study anonymous markets, a competitive equilibrium I would like to thank Paul Klemperer, Margaret Meyer, Peyton Young and especially Marzena Rostek for helpful conversations. yUniversity of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Economics, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 assumes the following preconditions 1) all traders freely and optimally adjust traded quant- ities to prices; 2) trade occurs in centralized anonymous markets; and 3) individual traders are negligible and hence treat prices parametrically. -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

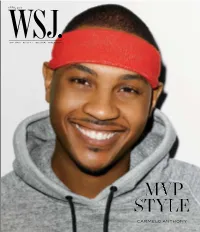

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Multi-Pose Interactive Linkage Design Teaser

EUROGRAPHICS 2019 / P. Alliez and F. Pellacini Volume 38 (2019), Number 2 (Guest Editors) Multi-Pose Interactive Linkage Design Teaser G. Nishida1 , A. Bousseau2 , D. G. Aliaga1 1Purdue University, USA 2Inria, France a) b) e) f) Fixed bodies Moving bodies c) d) Figure 1: Interactive design of a multi-pose and multi-body linkage. Our system relies on a simple 2D drawing interface to let the user design a multi-body object including (a) fixed bodies, (b) moving bodies (green and purple shapes), (c) multiple poses for each moving body to specify the desired motion, and (d) a desired region for the linkage mechanism. Then, our system automatically generates a 2.5D linkage mechanism that makes the moving bodies traverse all input poses in a desired order without any collision (e). The system also automatically generates linkage parts ready for 3D printing and assembly (f). Please refer to the accompanying video for a demonstration of the sketching interface and animations of the resulting mechanisms. Abstract We introduce an interactive tool for novice users to design mechanical objects made of 2.5D linkages. Users simply draw the shape of the object and a few key poses of its multiple moving parts. Our approach automatically generates a one-degree-of- freedom linkage that connects the fixed and moving parts, such that the moving parts traverse all input poses in order without any collision with the fixed and other moving parts. In addition, our approach avoids common linkage defects and favors compact linkages and smooth motion trajectories. Finally, our system automatically generates the 3D geometry of the object and its links, allowing the rapid creation of a physical mockup of the designed object. -

Computing in Mechanism Design∗

Computing in Mechanism Design¤ Tuomas Sandholm Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 1. Introduction Computational issues in mechanism design are important, but have received insufficient research interest until recently. Limited computing hinders mechanism design in several ways, and presents deep strategic interactions between com- puting and incentives. On the bright side, the vast increase in computing power has enabled better mechanisms. Perhaps most interestingly, limited computing of the agents can be used as a tool to implement mechanisms that would not be implementable among computationally unlimited agents. This chapter briefly reviews some of the key ideas, with the goal of alerting the reader to the importance of these issues and hopefully spurring future research. I will discuss computing by the center, such as an auction server or vote aggregator, in Section 2. Then, in Section 3, I will address the agents’ computing, be they human or software. 2. Computing by the center Computing by the center plays significant roles in mechanism design. In the following three subsections I will review three prominent directions. 2.1. Executing expressive mechanisms As algorithms have advanced drastically and computing power has increased, it has become feasible to field mecha- nisms that were previously impractical. The most famous example is a combinatorial auction (CA). In a CA, there are multiple distinguishable items for sale, and the bidders can submit bids on self-selected packages of the items. (Sometimes each bidder is also allowed to submit exclusivity constraints of different forms among his bids.) This increase in the expressiveness of the bids drastically reduces the strategic complexity that bidders face. -

Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University Law Review Volume 83 Issue 1 2005 Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution Matthew J. Brauer Princeton University Barbara Forrest Southeastern Louisiana University Steven G. Gey Florida State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Education Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Religion Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Matthew J. Brauer, Barbara Forrest, and Steven G. Gey, Is It Science Yet?: Intelligent Design Creationism and the Constitution, 83 WASH. U. L. Q. 1 (2005). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Quarterly VOLUME 83 NUMBER 1 2005 IS IT SCIENCE YET?: INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONISM AND THE CONSTITUTION MATTHEW J. BRAUER BARBARA FORREST STEVEN G. GEY* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................... 3 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. -

Matthew O. Jackson

Matthew O. Jackson Department of Economics Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6072 (650) 723-3544, fax: 725-5702, [email protected] http://www.stanford.edu/ jacksonm/ ⇠ Personal: Born 1962. Married to Sara Jackson. Daughters: Emilie and Lisa. Education: Ph.D. in Economics from the Graduate School of Business, Stanford Uni- versity, 1988. Bachelor of Arts in Economics, Summa Cum Laude, Phi Beta Kappa, Princeton University, 1984. Full-Time Appointments: 2008-present, William D. Eberle Professor of Economics, Stanford Univer- sity. 2006-2008, Professor of Economics, Stanford University. 2002-2006, Edie and Lew Wasserman Professor of Economics, California Institute of Technology. 1997-2002, Professor of Economics, California Institute of Technology. 1996-1997, IBM Distinguished Professor of Regulatory and Competitive Practices MEDS department (Managerial Economics and Decision Sci- ences), Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern Univer- sity. 1995-1996, Mechthild E. Nemmers Distinguished Professor MEDS, Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University. 1993-1994 , Professor (MEDS), Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University. 1991-1993, Associate Professor (MEDS), Kellogg Graduate School of Man- agement, Northwestern University. 1988-1991, Assistant Professor, (MEDS), Kellogg Graduate School of Man- agement, Northwestern University. Honors : Jean-Jacques La↵ont Prize, Toulouse School of Economics 2020. President, Game Theory Society, 2020-2022, Exec VP 2018-2020. Game Theory Society Fellow, elected 2017. John von Neumann Award, Rajk L´aszl´oCollege, 2015. Member of the National Academy of Sciences, elected 2015. Honorary Doctorate (Doctorat Honoris Causa), Aix-Marseille Universit´e, 2013. Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in Humanities and Sciences, Stanford, 2013. Distinguished Teaching Award: Stanford Department of Economics, 2012. -

The Design Argument

The design argument The different versions of the cosmological argument we discussed over the last few weeks were arguments for the existence of God based on extremely abstract and general features of the universe, such as the fact that some things come into existence, and that there are some contingent things. The argument we’ll be discussing today is not like this. The basic idea of the argument is that if we pay close attention to the details of the universe in which we live, we’ll be able to see that that universe must have been created by an intelligent designer. This design argument, or, as its sometimes called, the teleological argument, has probably been the most influential argument for the existence of God throughout most of history. You will by now not be surprised that a version of the teleological argument can be found in the writings of Thomas Aquinas. You will by now not be surprised that a version of the teleological argument can be found in the writings of Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas is noting that things we observe in nature, like plants and animals, typically act in ways which are advantageous to themselves. Think, for example, of the way that many plants grow in the direction of light. Clearly, as Aquinas says, plants don’t do this because they know where the light is; as he says, they “lack knowledge.” But then how do they manage this? What does explain the fact that plants grow in the direction of light, if not knowledge? Aquinas’ answer to this question is that they must be “directed to their end” -- i.e., designed to be such as to grow toward the light -- by God. -

Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy In Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy, Erik J. Engstrom offers an important, historically grounded perspective on the stakes of congressional redistricting by evaluating the impact of gerrymandering on elections and on party control of the U.S. national government from 1789 through the reapportionment revolution of the 1960s. In this era before the courts supervised redistricting, state parties enjoyed wide discretion with regard to the timing and structure of their districting choices. Although Congress occasionally added language to federal- apportionment acts requiring equally populous districts, there is little evidence this legislation was enforced. Essentially, states could redistrict largely whenever and however they wanted, and so, not surpris- ingly, political considerations dominated the process. Engstrom employs the abundant cross- sectional and temporal varia- tion in redistricting plans and their electoral results from all the states— throughout U.S. history— in order to investigate the causes and con- sequences of partisan redistricting. His analysis -

Supermodular Mechanism Design

Theoretical Economics 5(2010),403–443 1555-7561/20100403 Supermodular mechanism design L M Department of Economics, University of Texas This paper introduces a mechanism design approach that allows dealing with the multiple equilibrium problem, using mechanisms that are robust to bounded ra- tionality. This approach is a tool for constructing supermodular mechanisms, i.e., mechanisms that induce games with strategic complementarities. In quasilinear environments, I prove that if a social choice function can be implemented by a mechanism that generates bounded strategic substitutes—as opposed to strate- gic complementarities—then this mechanism can be converted into a supermod- ular mechanism that implements the social choice function. If the social choice function also satisfies some efficiency criterion, then it admits a supermodular mechanism that balances the budget. Building on these results, I address the multiple equilibrium problem. I provide sufficient conditions for a social choice function to be implementable with a supermodular mechanism whose equilibria are contained in the smallest interval among all supermodular mechanisms. This is followed by conditions for supermodular implementability in unique equilib- rium. Finally, I provide a revelation principle for supermodular implementation in environments with general preferences. K.Implementation,mechanisms,multipleequilibriumproblem,learn- ing, strategic complementarities, supermodular games. JEL .C72,D78,D83. 1. I For the economist designing contracts, taxes, or other institutions, there is a dilemma between the simplicity of a mechanism and the multiple equilibrium problem. On the one hand, simple mechanisms often restrict attention to the “right” equilibria. In public good contexts, for example, most tax schemes overlook inefficient equilibrium situa- tions, provided that one equilibrium outcome is a social optimum. -

Formation of Coalition Structures As a Non-Cooperative Game

Formation of coalition structures as a non-cooperative game Dmitry Levando, ∗ Abstract We study coalition structure formation with intra and inter-coalition externalities in the introduced family of nested non-cooperative si- multaneous finite games. A non-cooperative game embeds a coalition structure formation mechanism, and has two outcomes: an alloca- tion of players over coalitions and a payoff for every player. Coalition structures of a game are described by Young diagrams. They serve to enumerate coalition structures and allocations of players over them. For every coalition structure a player has a set of finite strategies. A player chooses a coalition structure and a strategy. A (social) mechanism eliminates conflicts in individual choices and produces final coalition structures. Every final coalition structure is a non-cooperative game. Mixed equilibrium always exists and consists arXiv:2107.00711v1 [cs.GT] 1 Jul 2021 of a mixed strategy profile, payoffs and equilibrium coalition struc- tures. We use a maximum coalition size to parametrize the family ∗Moscow, Russian Federation, independent. No funds, grants, or other support was received. Acknowledge: Nick Baigent, Phillip Bich, Giulio Codognato, Ludovic Julien, Izhak Gilboa, Olga Gorelkina, Mark Kelbert, Anton Komarov, Roger Myerson, Ariel Rubinstein, Shmuel Zamir. Many thanks for advices and for discussion to participants of SIGE-2015, 2016 (an earlier version of the title was “A generalized Nash equilibrium”), CORE 50 Conference, Workshop of the Central European Program in Economic Theory, Udine (2016), Games 2016 Congress, Games and Applications, (2016) Lisbon, Games and Optimization at St Etienne (2016). All possible mistakes are only mine. E-mail for correspondence: dlevando (at) hotmail.ru.