Land-Use Planning in the Doldrums: Growth Management in Massachusetts’ I-495 Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 Application of Comcast Corporation, General Electric Company

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 Application of Comcast Corporation, ) General Electric Company and NBC ) Universal, Inc., for Consent to Assign ) MB Docket No. 10-56 Licenses or Transfer Control of ) Licenses ) COMMENTS AND MERGER CONDITIONS PROPOSED BY ALLIANCE FOR COMMUNICATIONS DEMOCRACY James N. Horwood Gloria Tristani Spiegel & McDiarmid LLP 1333 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 879-4000 June 21, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PEG PROGRAMMING IS ESSENTIAL TO PRESERVING LOCALISM AND DIVERSITY ON BEHALF OF THE COMMUNITY, IS VALUED BY VIEWERS, AND MERITS PROTECTION IN COMMISSION ACTION ON THE COMCAST-NBCU TRANSACTION .2 II. COMCAST CONCEDES THE RELEVANCE OF AND NEED FOR IMPOSING PEG-RELATED CONDITIONS ON THE TRANSFER, BUT THE PEG COMMITMENTS COMCAST PROPOSES ARE INADEQUATE 5 A. PEG Merger Condition No.1: As a condition ofthe Comcast NBCU merger, Comcast should be required to make all PEG channels on all ofits cable systems universally available on the basic service tier, in the same format as local broadcast channels, unless the local government specifically agrees otherwise 8 B. PEG Merger Condition No.2: As a merger condition, the Commission should protect PEG channel positions .,.,.,.. ., 10 C. PEG Merger Condition No.3: As a merger condition, the Commission should prohibit discrimination against PEG channels, and ensure that PEG channels will have the same features and functionality, and the same signal quality, as that provided to local broadcast channels .,., ., ..,.,.,.,..,., ., ., .. .,11 D. PEG Merger Condition No.4: As a merger condition, the Commission should require that PEG-related conditions apply to public access, and that all PEG programming is easily accessed on menus and easily and non-discriminatorily accessible on all Comcast platforms ., 12 CONCLUSION 13 EXHIBIT 1 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. -

Older Workers Rock! We’Re Not Done Yet!

TM TM Operation A.B.L.E. 174 Portland Street Tel: 617.542.4180 5th Floor E: [email protected] Boston, MA 02114 W: www.operationable.net Older Workers Rock! We’re Not Done Yet! A.B.L.E. SCSEP Office Locations: SCSEP Suffolk County, MA Workforce Central SCSEP Hillsborough County, NH 174 Portland Street, 5th Floor 340 Main Street 228 Maple Street., Ste 300 Boston, MA 02114 Ste.400 Manchester, NH 03103 Phone: 617.542.4180 Worcester, MA 01608 Phone: 603.206.4405 eMail: [email protected] Tel: 508.373.7685 eMail: [email protected] eMail: [email protected] SCSEP Norfolk, Metro West & SCSEP Coos County, NH Worcester Counties, MA Career Center 961 Main Street Quincy SCSEP Office of North Central MA Berlin, NH 03570 1509 Hancock Street, 4th Floor 100 Erdman Way Phone: 603.752.2600 Quincy, MA 02169 Leominster, MA 01453 eMail: [email protected] Phone: 617-302-2731 Tel: 978.534.1481 X261 and 617-302-3597 eMail: [email protected] eMail: [email protected] South Middlesex GETTING WORKERS 45+ BACK TO WORK SINCE 1982 SCSEP Essex & Middlesex Opportunity Council Counties, MA 7 Bishop Street Job Search Workshops | Coaching & Counseling | Training | ABLE Friendly Employers | Resource Room Framingham, MA 01702 280 Merrimack Street Internships | Apprenticeships | Professional Networking | Job Clubs | Job Seeker Events Building B, Ste. 400 Tel: 508.626.7142 Lawerence, MA 01843 eMail: [email protected] Phone: 978.651.3050 eMail: [email protected] 2018 Annual Report September 2018 At Operation A.B.L.E., we work very hard to Operation A.B.L.E. Addresses the Changing Needs keep the quality of our programs up and our costs down. -

Transpo Transcript.Indd

October 2013 Using Technology to Improve Transportation: All Electronic-Tolling and Beyond Transcript Introduction customer-facing and most customer- Underinvestment has put pressure on focused of all government services. STEVE POFTAK: Thanks to all of transportation providers to improve service. Trust in government is another aspect Fiscal pressures have limited the resources you for coming today and joining us. available to make those improvements. of transportation. And technology is a I’d also like to thank our partners who Technology off ers the opportunity to way for us to show our customers that leverage smaller investments by improving have put this together: Joseph Giglio customer services, enhancing operating we can improve their experience. from the Center for Strategic Studies effi ciencies, and increasing revenue. at the D’Amore-McKim School of I think the gold standard in our To explore the potential of new technologies to make transportation Business at Northeastern University business is giving more time back work more effi ciently, faster, and safer, the and Greg Massing at the Rappaport to people. Whether it’s standing on conference “Using Technology to Improve Transportation: All-Electronic Tolling and Center for Law and Public Service at a platform at Alewife or standing in Beyond” was held on May 7, 2013 at the Suffolk University. line at the Registry of Motor Vehicles, Suff olk University Law School. it is giving people more time back. Here in Massachusetts, we’ve just The Conference was co-sponsored by The Technology holds tremendous promise Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, The gone through another round of Center for Strategic Studies at the D’Amore- to accomplish these goals that we have legislative and executive branch McKim School of Business at Northeastern in transportation. -

RAPPAPORT POLICY BRIEFS Instituterappaport for Greater Boston INSTITUTE Kennedy Schoolfor of Government, Greater Harvard University Boston June 2008

RAPPAPORT POLICY BRIEFS InstituteRAPPAPORT for Greater Boston INSTITUTE Kennedy Schoolfor of Government, Greater Harvard University Boston June 2008 Reducing Youth Violence: Lessons from the Boston Youth Survey By Renee M. Johnson, Deborah Azrael, Mary Vriniotis, and David Hemenway, Harvard School of Public Health In Boston, as in many other cities, aggressive behavior, assault, weapon Rappaport Institute Policy Briefs are short youth violence takes an unacceptably carrying, feelings of safety, and overviews of new scholarly research on important issues facing the region. This high toll. Reducing the burden of gang membership. It also inquired brief reports on the results of the Boston youth violence is a priority for the about risk and protective factors for Youth Survey 2006 (BYS), an in-school survey of Boston high school youth conducted City’s policymakers, civic leaders, violence (e.g., alcohol and drug use, biennially by the Harvard Youth Violence Prevention Center in collaboration with the and residents. To date, however, depressive symptoms, family violence, City of Boston. More information is available little information has been available developmental assets, academic at www.hsph.harvard.edu/hyvpc/research/. about the prevalence, antecedents and performance, perceptions of collective Renee M. Johnson impacts of youth violence in Boston. effi cacy within one’s neighborhood), Renee M. Johnson is a Research Associate at the Harvard School of Public Health and The Boston Youth Survey (BYS) and health behaviors (e.g., nutrition Core Faculty at the Harvard Youth Violence and physical activity). Although 1,233 Prevention Center. addresses this gap in knowledge. It is Deborah Azrael students took the survey, the analytical an in-school survey of Boston high Deborah Azrael is a Research Associate at the school students conducted by the sample includes only the 1,215 who Harvard School of Public Health. -

Boston Bound: a Comparison of Boston’S Legal Powers with Those of Six Other Major American Cities by Gerald E

RAPPAPORT POLICY BRIEFS Institute for Greater Boston Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University December 2007 Boston Bound: A Comparison of Boston’s Legal Powers with Those of Six Other Major American Cities By Gerald E. Frug and David J. Barron, Harvard Law School Boston is an urban success story. It cities — Atlanta, Chicago, Denver, Rappaport Institute Policy Briefs are short has emerged from the fi nancial crises New York City, San Francisco, and overviews of new and notable scholarly research on important issues facing the of the 1950s and 1960s to become Seattle — enjoy to shape its own region. The Institute also distributes a diverse, vital, and economically future. It is hard to understand why Rappaport Institute Policy Notes, a periodic summary of new policy-related powerful city. Anchored by an the Commonwealth should want its scholarly research about Greater Boston. outstanding array of colleges and major city—the economic driver This policy brief is based on “Boston universities, world-class health of its most populous metropolitan Bound: A Comparison of Boston’s Legal Powers with Those of Six Other care providers, leading fi nancial area—to be constrained in a way Major American Cities,” a report by Frug and Barron published by The Boston institutions, and numerous other that comparable cities in other states Foundation. The report is available assets, today’s Boston drives the are not. Like Boston, the six cities online at http://www.tbf.org/tbfgen1. asp?id=3448. metropolitan economy and is one of are large, economically infl uential the most exciting and dynamic cities actors within their states and regions, Gerald E. -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Community Partners Directory R

COMMUNITY PARTNERS DIRECTORY R 1 2 Table of Contents Message from the Executive Director………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 ORI Program Descriptions……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 ORI Providers Listed by Service Type…………………………………………………………………………………… 7 ORI Provider Service Map……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 Provider Summaries………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….. 12 EOHHS State Agencies…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 34 3 The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services Office for Refugees and Immigrants 600 Washington Street, 4th Floor Boston, Massachusetts 02111 CHARLES D. BAKER Tel: (617) 727-7888 Governor Fax: (617) 727-1822 TTY: (617) 727-8147 KARYN E. POLITO Lieutenant Governor MARYLOU SUDDERS MARY TRUONG Secretary Executive Director March 15, 2018 Dear Community Partners and Friends, When we released our first edition of the Community Partners Directory, it delighted us to hear how well-received it was, especially by our community partners and stakeholders here in Massachusetts. It is with that same enthusiasm that we release an updated edition of the Community Partners Directory in a user-friendly format. This new edition features a list of all ORI programs with a brief description of each, followed by a list of the providers that offer each program. After, the directory lists each provider more thoroughly, including their contact information and location. It is our hope that this directory will allow community partners and stakeholders to collaborate in order to best serve the immigrants and refugees residing in Massachusetts. Every effort has been made to ensure that this directory is accurate and up to date. This second edition is special because it includes ORI’s new partners for the newest addition to ORI’s portfolio of programs, the Financial Literacy for Newcomers (FLNP). -

Emergency Services Program (Esps)

Emergency Services Program (ESPs) Emergency Service Programs (ESPs) provide community-based assessment, intervention, and stabilization services for people experiencing mental health or substance use related crisis. hey can tal! to people "ho feel they are in or near crisis, and try to help them find the supports they need to manage the crisis. ESPs are available #$ hours a day, % days a "ee!, &'( days a year. Statewide ESP )umber Call 1-877-382-1609 and enter your zipcode (or use the direct number belo") )ortheastern *assachusetts +mesbury, ,everly, ,oxford, -anvers, Essex, .eorgeto"n, .loucester, 3ahey4)ortheast .roveland, /amilton, /averhill, 0ps"ich, *anchester by the Sea, North Essex *arblehead, *errimac, *iddleton, )e"bury, )e"buryport, Peabody, ,ehavioral /ealth 1oc!port, 1o"ley, Salem, Salisbury, opsfield, 2enham, 2est )e"bury 1-866-523-1216 +ndover, 3a"rence, *ethuen, )orth +ndover 3ahey4)ortheast a!rence ,ehavioral /ealth area 1-877-255-1261 ,illerica, 5helmsford, -racut, -unstable, 3o"ell, e"!sbury, yngsboro, 3ahey4)ortheast o!ell area 2estford ,ehavioral /ealth 1-800-830-5177 Everett, 3ynn, 3ynnfield, *alden, *edford, *elrose, )ahant, )orth 1eading, Eliot Community "ri-City 1eading, Saugus, Stoneham, S"ampscott, 2a!efield /uman Services 1-800-988-1111 *etro ,oston ,oston Boston, Broo!line, Chelsea, Revere, Winthrop ,oston Emergency #oston area Services eam 1-800-981-$357 5ambridge, Somerville Cambridge Somerville Ca%&rid'e ( Emergency Services So%er*ille 1-800-981-$357 Southeastern *assachusetts ,raintree, Cohasset, Hingham, -

TOWN of ACTON 2020 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Town of Acton

TOWN TOWN ACTON OF 2020 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT TOWN ANNUAL 2020 TOWN OF ACTON 2020 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT Town of Acton Incorporated as a Town: July 3, 1735 Type of Government: Town Meetings ~ Board of Selectmen/Town Manager Location: Eastern Massachusetts, Middlesex County, bordered on the east by Carlisle and Concord, on the west by Boxborough, on the north by Westford and Littleton, on the south by Sudbury, and on the southwest by Stow and Maynard. Elevation at Town Hall: 268’ above mean sea level Land Area: Approximately 20 square miles Population: Year Persons 1950 3,510 1960 7.238 1970 14,770 1980 19,000 1990 18,144 2000 20,331 2010 21,936 2020 22,170 Report Cover: (Top and Bottom Left) Groundbreaking at the North Acton Fire Station; (Top and Bottom Right) Ribbon Cutting Ceremony for the Miracle Field Sports Pavilion Photos courtesy of Town Staff 2020 Annual Reports Town of Acton, Massachusetts Two Hundred and Eighty Fifth Municipal Year For the year ending December 31, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Administrative Services 8. Public Works Board of Selectmen 4 DPW/Highway 96 Town Manager 5 Green Advisory Board 97 Public Facilities 99 2. Financial Management Services Board of Assessors 8 9. Community Safety House Sales 9 Animal Control Officer 101 Finance Committee 18 Animal Inspector 101 Town Accountant 18 Emergency Management Agency 101 Fire Department 101 3. Human Services Auxiliary Fire Department 109 Acton Housing Authority 28 Police Department 109 Acton Nursing Services 29 Commission on Disabilities 31 10. Legislative Community Housing Corporation 32 Annual Town Meeting, June 29, 2020 116 Community Services Coordinator 35 Special Town Meeting, September 8, 2020 127 Council on Aging 35 Health Insurance Trust 37 11. -

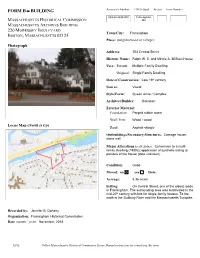

FORM B BUILDING Assessor’S Number USGS Quad Area(S) Form Number

FORM B BUILDING Assessor’s Number USGS Quad Area(s) Form Number 069-68-4339-000 Framingham, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MA MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD Town/City: Framingham BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Place: (neighborhood or village): Photograph Address: 703 Central Street Historic Name: Ralph W. E. and Minnie A. Milliken House Uses: Present: Multiple Family Dwelling Original: Single Family Dwelling Date of Construction: Late 19th century Source: Visual Style/Form: Queen Anne / Complex Architect/Builder: Unknown Exterior Material: Foundation: Parged rubble stone Wall/Trim: Wood / wood Locus Map (North is Up) Roof: Asphalt shingle Outbuildings/Secondary Structures: Carriage house, stone wall Major Alterations (with dates): Conversion to a multi- family dwelling (1980s); application of synthetic siding to portions of the house (date unknown) Condition: Good Moved: no yes Date: Acreage: 5.36 acres On Central Street, one of the oldest roads Setting: in Framingham. The surrounding area was subdivided in the mid-20th century with lots for single-family houses. To the north is the Sudbury River and the Massachusetts Turnpike. Recorded by: Jennifer B. Doherty Organization: Framingham Historical Commission Date (month / year): November, 2018 12/12 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM B CONTINUATION SHEET FRAMINGHAM 703 CENTRAL STREET MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area(s) Form No. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. -

CHANGING FACES of GREATER BOSTON a REPORT from BOSTON INDICATORS, the BOSTON FOUNDATION, UMASS BOSTON and the UMASS DONAHUE INSTITUTE the PROJECT TEAM

CHANGING FACES of GREATER BOSTON A REPORT FROM BOSTON INDICATORS, THE BOSTON FOUNDATION, UMASS BOSTON AND THE UMASS DONAHUE INSTITUTE THE PROJECT TEAM BOSTON INDICATORS is the research center at the UMASS BOSTON (UMB) is one of only two universities in Boston Foundation, which works to advance a thriving Greater the country with free-standing research institutes dedicated to Boston for all residents across all neighborhoods. We do this four major communities of color in the U.S. Working together by analyzing key indicators of well-being and by researching and individually, these institutes offer thought leadership to promising ideas for making our city more prosperous, equitable help shape public understanding of the evolving racial and and just. To ensure that our work informs active efforts to ethnic diversities in Boston, Massachusetts, and beyond. improve our city, we work in deep partnership with community The four research institutes are: groups, civic leaders and Boston’s civic data community to THE INSTITUTE FOR ASIAN AMERICAN produce special reports and host public convenings. STUDIES (IAAS) utilizes resources and expertise from THE BOSTON FOUNDATION is is one of the largest the university and the community to conduct research and oldest community foundations in America, with net assets on Asian Americans; to strengthen and further Asian of $1.3 billion. The Foundation is a partner in philanthropy, with American involvement in political, economic, social, and some 1,100 charitable funds established for the general benefit cultural life; and to improve opportunities and campus of the community or for special purposes. It also serves as a life for Asian American faculty, staff, and students and for major civic leader, think tank and advocacy organization dedi- those interested in Asian Americans. -

How Massachusetts Can Stop the Public-Sector Virus by Thomas A

March 2011 How Massachusetts Can Stop the Public-Sector Virus By Thomas A. Kochan (MIT Sloan School of Management) America is in the early stages of what are these the causes or convenient This Policy Brief is based on remarks could be the largest labor protest of scapegoats and targets? made by Professor Thomas A. Kochan our lifetime. Starting in Wisconsin, at “Collective Bargains: Rebuilding and Let me be clear about the deeper issue Repairing Public Sector Labor Relations the battle over public-sector wages, at stake in these debates that give them in Diffi cult Times,” a Boston 101 event on benefi ts, and collective bargaining February 23, 2011. A full video of the event such a viral character. Wisconsin’s can be found at http://www.hks.harvard. rights is now spreading like a virus to governor would strip employees of edu/centers/rappaport/events-and-news/ Indiana, Ohio, New Jersey, and God audio-and-video-clips/collective-bargains- their rights to collective bargaining rebuilding-and-repairing-public-sector- knows where next. So, like exposure and make it essentially impossible labor-relations-in-diffi cult-times. to any virus, we have two questions for any union to represent its Thomas A. Kochan on our mind: Will we get it here in Thomas A. Kochan is the George M. Bunker members in a stable and responsible Professor at MIT Sloan School of Massachusetts? Is there a treatment fashion. In doing so, he is attacking a Management. He is also co-Director at the that makes us immune and stops it MIT Institute for Work and Employment fundamental human right, the freedom Research.