The Architecture of Local Performance: Stages of the Taliesin Fellowship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors,Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of I

Figure 1. Graycliff exterior. 2001 WAG Postprints—Dallas, Texas Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors, Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of Isabelle Martin Pamela Kirschner Abstract Information was gathered in a study of the interior color scheme, fabrics and furni- ture of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed house Graycliff. The house is situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Erie in Derby, New York. It was designed by Wright in 1926 for Isabelle Martin, the wife of the industrialist Darwin Martin. Wright designed both freestanding and built-in furniture for the house interior and also suggested colors and fabrics. Extensive written documentation and original photographs found in the archives of the State University of New York at Buffalo have been utilized to determine the colors, materials and furniture original to the house. Physical evidence found on the remaining original furniture, moldings and upholstered pillows provides informa- tion about fi nishes, construction and show cover fabrics. Information on historic methods and materials from the period is provided for comparison with the physi- cal evidence along with scientifi c analysis of fi nishes. The conservation treatment methods are also discussed. This technical and historical information is helpful for conservators and curators to better understand the materials and construction used in Frank Lloyd Wright designs during this time period. It also promotes the proper care and conservation treatment of these objects while preserving original fi nishes and the historic intent of the house. Introduction Graycliff was the summer estate of Isabelle R. and Darwin D. Martin and is located on the cliffs above Lake Erie in Derby, New York, fourteen miles south of Buffalo. -

Oak Park Area Visitor Guide

OAK PARK AREA VISITOR GUIDE COMMUNITIES Bellwood Berkeley Broadview Brookfield Elmwood Park Forest Park Franklin Park Hillside Maywood Melrose Park Northlake North Riverside Oak Park River Forest River Grove Riverside Schiller Park Westchester www.visitoakpark.comvisitoakpark.com | 1 OAK PARK AREA VISITORS GUIDE Table of Contents WELCOME TO THE OAK PARK AREA ..................................... 4 COMMUNITIES ....................................................................... 6 5 WAYS TO EXPERIENCE THE OAK PARK AREA ..................... 8 BEST BETS FOR EVERY SEASON ........................................... 13 OAK PARK’S BUSINESS DISTRICTS ........................................ 15 ATTRACTIONS ...................................................................... 16 ACCOMMODATIONS ............................................................ 20 EATING & DRINKING ............................................................ 22 SHOPPING ............................................................................ 34 ARTS & CULTURE .................................................................. 36 EVENT SPACES & FACILITIES ................................................ 39 LOCAL RESOURCES .............................................................. 41 TRANSPORTATION ............................................................... 46 ADVERTISER INDEX .............................................................. 47 SPRING/SUMMER 2018 EDITION Compiled & Edited By: Kevin Kilbride & Valerie Revelle Medina Visit Oak Park -

Graycliff – a Truly American Story “In His Unshakable Optimism

Graycliff – A Truly American Story “In his unshakable optimism, messianic zeal, and pragmatic resilience, Wright was quintessentially American.” ‐ Smithsonian magazine tribute on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Guggenheim. Just as it is often said that Frank Lloyd Wright was truly American in spirit and style, the Graycliff story is woven out of strands that also have a truly American flavor. The American Dream, embodying the notion of opportunity for all, takes shape here in the true-to-life rags-to-riches story of Darwin Martin. The close cousin to the American Dream – the one that holds that through gumption and perseverance one may triumph – is on display as well. Perseverance, resilience, and the comeback story are all in evidence at various stages in Graycliff’s 90 years – for the Martins, for Wright himself, for the house, the region, and for the Graycliff Conservancy as an organization. Win-win relationships where all parties pragmatically get their needs met are both a hallmark of American history and culture and a defining characteristic of relationships at Graycliff where all the key players compromised a little while holding onto their defining principles in the end. One of the most enduring and distinctive American values is the lure and promise of nature, wilderness, and the frontier and the potential of new beginnings that are implicit in the purity of nature and the fresh start that movement to a new place makes possible. This is evident in both the post-retirement reboot for the Martin family at Graycliff and the property’s roots in organic architecture in which the house rose from the lands on which it sits. -

New Oral History Projects Launched!

BOARD OF DIRECTORS Anthony C. Wood, Chair Elizabeth R. Jeffe, Vice-Chair Stephen Facey, Treasurer Lisa Ackerman, Secretary Daniel J. Allen Eric Allison Michele H. Bogart Joseph M. Ciccone Susan De Vries Amy Freitag Shirley Ferguson Jenks Otis Pratt Pearsall Duane A. Watson NEWSLETTER SPRING 2012 Welcome to the sixteenth edition of the newsletter of the New York Preservation Archive Project. The mission of the New York Preservation Archive Project is to protect and raise awareness of the narratives of historic preservation in New York. Through public programs, outreach, celebration, and the creation of public access to information, the Archive Project hopes to bring these stories to light. New Oral History Projects Launched! The Archive Project Embarks Upon Ambitious Array of Interviews with Preservation Leaders The New York Preservation Archive Project is from the Robert A. and Elizabeth R. Jeffe range of cultural, historical, and architectural thrilled to announce the launch of our newest Foundation. aspects of the city. Each individual house has oral history initiative, Leading the Movement: * * * a distinctive preservation history and a unique Interviews with Preservationist Leaders in New For the first time in our organization’s history, set of people who ensured its survival, whether York’s Civic Sector. The goal of this project is the Archive Project is teaming up with New they were concerned citizens, directors of civic to record oral histories with 15 key leaders in York University’s Museum Studies Program organizations, or descendents of the houses’ the preservation civic sector, capturing their to produce a series of oral histories focused original inhabitants. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Download Pamphlets on Labor Law, Tort Immunity and Other Subjects from the Ancel Glink Library

OCTOBER 2011 | VOLUME XXIX ISSUE 5 ILLINOIS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION ILLINOIS LIBRARY The Illinois Library Association Reporter is a forum for those who are improving and reinventing Illinois libraries, with articles that seek to: explore new ideas and practices from all types of libraries and library systems; examine the challenges facing the profession; and inform the library community and its supporters with news and comment about important issues. The ILA Reporter is produced and circulated with the purpose of enhancing and supporting the value of libraries, which provide free and equal access to information. This access is essential for an open democratic society, an informed electorate, and the advancement of knowledge for all people. ON THE COVER This drawing of the interior of the B. Harley Bradley House in Kankakee is among the drawings in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wasmusth Portfolio in the special collections of the Oak Park Public Library. The house was designed in 1900 for Harley and Anna Hickox Bradley, arguably Wright’s first acknowledged Prairie-style design. Built along the Kankakee River, it’s a perfect example of Wright’s idea to design an entire house including the interiors as well. See article beginning on page 8. The Illinois Library Association is the voice for Illinois libraries and the millions who depend The Illinois Library Association has three full-time staff members. It is governed by on them. It provides leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of a sixteen-member executive board, made up of elected officers. The association library services in Illinois and for the library community in order to enhance learning and employs the services of Kolkmeier Consulting for legislative advocacy. -

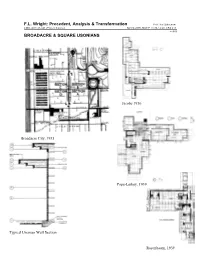

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

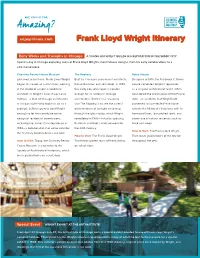

Frank Lloyd Wright Itinerary

enjoyillinois.com Frank Lloyd Wright Itinerary Early Works and Triumphs in Chicago A YOUNG ARCHITECT BUILDS HIS REPUTATION IN THE WINDY CITY Spend a day in Chicago exploring some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most famous designs, from his early collaborations to a solo masterpiece. Charnley-Persky House Museum The Rookery Robie House Like most in his trade, Frank Lloyd Wright Built by Chicago’s preeminent architects, Designed in 1910, the Frederick C. Robie began his career as a draftsman, working Daniel Burnham and John Root, in 1888, House cemented Wright’s reputation in the studio of a more established this early iron skyscraper is notable as a singular architectural talent. Often architect. In Wright’s case, it was Louis enough for its history in Chicago considered the crown jewel of the Prairie Sullivan—a titan of Chicago architecture architecture. But the real reason to style—an aesthetic that Wright both in his own right—who took him on as a visit The Rookery is to see the careful pioneered and perfected—the home protégé. Sullivan grew to trust Wright orchestrations of sunlight streaming reflects the Midwest’s flat plains with its enough to let him contribute to the through the glass lobby, which Wright horizontal lines, low-pitched roofs, and design of residential commissions, remodeled in 1905—instantly updating clever use of natural materials such as including the James Charnley House in Burnham and Root’s drab ironwork for brick and wood. 1892—a collaboration that some consider the 20th Century. How to Visit: The Frank Lloyd Wright the first truly modern American home. -

![The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1959 [ 1959]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9748/the-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum-1959-1959-1729748.webp)

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum 1959 [ 1959]

landmarks Preservation Commission August 14, 1990; Designation List 226 LP-1774 'IHE SQI.(M)N R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, 1071 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan. Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect. Built 1956-59. landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1500, I.ot 1. On December 12, 1989, the landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a landmark of the Guggenheim Museum and the proposed designation of the related landmark Site (Item No. 38). 'lhe hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Twenty-seven witnesses, including three representatives of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and Musemns, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters supporting designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Surmrary The Guggenheim Museum, an internationally recognized building, is one of New York's most architecturally irrportant buildings; located on prestigious Fifth Avenue, it is a link in that thoroughfare's highly regarded ''Museum Mile." Founded by Solomon R. Guggenheim, it is the best known of the many institutions financed by the philanthropy of the Guggenheim family, whose extraordinary wealth and subsequent social prominence were derived primarily from its worldwide mining empire. Inspired and led by the painter and art patron Hilla Rebay, Guggenheim supported many avant-garde painters of "non-objective" art by purchasing their works and, in 1937, establishing a foundation to promote art and education in art and the enlightenment of the public. Rebay eventually convinced him to commission in 1943 America's preeminent architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, to design the museum. -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D.