Epping Forest and Buffer Lands Deer Management Strategy Review Summary 23/03/20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day

Holly Marriott Webb Histories of Value Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day Master’s thesis in Global Environmental History 1 Abstract Marriott Webb, H. 2019. Histories of Value: Following Deer Populations Through the English Landscape from 1800 to the Present Day. Uppsala, Department of Archaeology and Ancient His- tory. Imagining the English landscape as an assemblage entangling deer and people throughout history, this thesis explores how changes in deer population connect to the ways deer have been valued from 1800 to the present day. Its methods are mixed, its sources are conversations – human voices in the ongoing historical negotiations of the multispecies body politic, the moot of people, animals, plants and things which shapes and orders the landscape assemblage. These conversations include interviews with people whose lives revolve around deer, correspondence with the organisations that hold sway over deer lives, analysis of modern media discourse around deer issues and exchanges with the history books. It finds that a non-linear increase in deer population over the time period has been accompanied by multiple changes in the way deer are valued as part of the English landscape. Ending with a reflection on how this history of value fits in to wider debates about the proper representation of animals, the nature of non-human agency, and trajectories of the Anthropocene, this thesis seeks to open up new ways of exploring questions about human- animal relationships in environmental history. Keywords: Assemblages, Deer, Deer population, England, Hunting, Landscape, Making killable, Moots, Multispecies, Nativist paradigm, Olwig, Pests, Place, Trash Animals, Tsing, United Kingdom, Wildlife management. -

Quaternary Science Reviews 42 (2012) 74E84

Author's personal copy Quaternary Science Reviews 42 (2012) 74e84 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Phylogeographic, ancient DNA, fossil and morphometric analyses reveal ancient and modern introductions of a large mammal: the complex case of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland Ruth F. Carden a,*, Allan D. McDevitt b, Frank E. Zachos c, Peter C. Woodman d, Peter O’Toole e, Hugh Rose f, Nigel T. Monaghan a, Michael G. Campana g, Daniel G. Bradley h, Ceiridwen J. Edwards h,i a Natural History Division, National Museum of Ireland (NMINH), Merrion Street, Dublin 2, Ireland b School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland c Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, Austria d 6 Brighton Villas, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland e National Parks and Wildlife Service, Killarney National Park, County Kerry, Ireland f Trian House, Comrie, Perthshire PH6 2HZ, Scotland, UK g Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, 11 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge 02138, USA h Molecular Population Genetics Laboratory, Smurfit Institute, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland i Research Laboratory for Archaeology, University of Oxford, Dyson Perrins Building, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK article info abstract Article history: The problem of how and when the island of Ireland attained its contemporary fauna has remained a key Received 29 November 2011 question in understanding Quaternary faunal assemblages. We assessed the complex history and origins Received in revised form of the red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Ireland using a multi-disciplinary approach. Mitochondrial sequences of 20 February 2012 contemporary and ancient red deer (dating from c 30,000 to 1700 cal. -

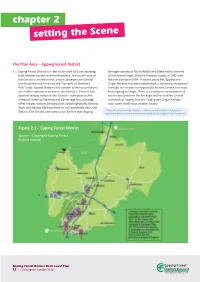

Chapter 2 Setting the Scene

chapter 2 setting the Scene The Plan Area – Epping Forest District 2.1 Epping Forest District is in the south-west of Essex abutting through stations at North Weald and Blake Hall to the end both Greater London and Hertfordshire. The south–west of of the line at Ongar. Blake Hall station closed in 1981 with the District is served by the London Underground Central the line closing in 1994. In recent years the ‘Epping and Line (both the main line and the ‘Hainault via Newbury Ongar Railway’ has been established, a nationally recognised Park’ loop). Epping Station is the eastern terminus and there heritage rail service running on this former Central Line track are 7 other stations in service in the District 1. There is one from Epping to Ongar. There is currently no operational rail national railway station in the District – at Roydon on the connection between the heritage rail line and the Central Liverpool Street to Stansted and Cambridge line, although Line track at Epping, but the ‘Epping and Ongar Railway’ other railway stations (Broxbourne, Sawbridgeworth, Harlow runs some shuttle bus services locally. Town and Harlow Mill) are close to, and accessible from, the 2 District. The Central Line used to run further than Epping, These are Theydon Bois, Debden, Loughton and Buckhurst Hill, together with the stations on the branch line at Roding Valley, Chigwell and Grange Hill Figure 2.1 – Epping Forest District Source – Copyright Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Draft Local Plan 12 | Consultation October 2016 2.2 The M25 runs east-west through the District, with a local road 2.6 By 2033, projections suggest the proportion of people aged interchange at Waltham Abbey. -

Ecology of Red Deer a Research Review Relevant to Their Management in Scotland

Ecologyof RedDeer A researchreview relevant to theirmanagement in Scotland Instituteof TerrestrialEcology Natural EnvironmentResearch Council á á á á á Natural Environment Research Council Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ecology of Red Deer A research review relevant to their management in Scotland Brian Mitchell, Brian W. Staines and David Welch Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Banchory iv Printed in England by Graphic Art (Cambridge) Ltd. ©Copyright 1977 Published in 1977 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology 68 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 11LA ISBN 0 904282 090 Authors' address: Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Hill of Brathens Glassel, Banchory Kincardineshire AB3 4BY Telephone 033 02 3434. The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to and draws upon the collective knowledge of the fourteen sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a Sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man-made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. Nearly half of ITE'Swork is research commissioned by customers, such as the Nature Conservancy Council who require information for wildlife conservation, the Forestry Commission and the Department of the Environment. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. -

H Ybridisation Among Deer and Its Implications for Conservation

H ybridisation among Deer and its implications for conservation RORY HARRINGTONl INTRODUCTION The Red Deer (Cervus elaphus scoticus Lonnberg, 1906) is generally considered to be the only native hoofed animal that has lived contemporaniously with man in Ireland (Charlesworth, 1963 and O'Rourke, 1970). Ecologically, the red deer appears to be an animal of the transition zone between forest and steppe (Dzieciolowski, 1969) and it was widely distributed in Ireland up to the mid-eighteenth century (Pococke, 1752; Moryson, 1735 and Scouler, 1833). The present distribution of the species in the wild is however confined to three of the thirty two counties of Ireland and only in County Kerry are the deer considered to be indigenous. The other two counties, Wicklow and Donegal, have stock of mainly alien origin. There is a general recognition of the threat that an alien red deer stock could present to the genetic integrity of the Irish race of red deer in county Kerry if these two red deer stocks were brought into contact. However, until recently few people realized that, in areas where red deer and the exotic Japanese sika deer (Cervus nippon Temminck) are living sympatrically (within the same geographical area) as in County Kerry, there is any threat of the two species hybridising. A current ecological study of red deer and sika deer in County Wicklow has produced evidence that clearly supports the early reports made by Powerscourt (1884), Brooke (\898) and F. W. B. (J 902) that red deer and sika deer can hybridise freely. The evid ed~e also indicates that hybridisation between these species is an insidious phenomonen which can result in an apparent total amal gamation of a red deer popUlation during a relatively [hort period of time. -

London Tube by Zuti

Stansted Airport Chesham CHILTERN Cheshunt WATFORD Epping RADLETT Stansted POTTERS BAR Theobolds Grove Amersham WALTHAM CROSS WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING FOREST Chalfont & Watford Latimer Junction Turkey Theydon ENFIELD Street Bois Watford BOREHAMWOOD London THREE RIVERS Cockfosters Enfield Town ELSTREE Copyright Visual IT Ltd OVERGROUND Southbury High Barnet Zuti and the Zuti logo are registered trademarks Chorleywood Watford Oakwood Loughton Debden High Street NEW BARNET www.zuti.co.uk Croxley BUSHEY Rickmansworth Bush Hill Park Chingford Bushey Buckhurst Hill Totteridge & Whetstone Southgate Moor Park EDGWARE Shenfield Stanmore Edmonton Carpenders Park Green Woodside Park Arnos Grove Grange Hill MAPLE CROSS Edgware Roding Chigwell Hatch End Silver Valley Northwood STANMORE JUBILEE MILL HILL EAST BARNET Street Mill Hill East West Finchley LAMBOURNE END Canons Park Bounds Green Highams Hainault Northwood Hills Headstone Lane White Hart Park Woodford Brentwood Lane NORTHWOOD Burnt Oak WALTHAM STANSTED EXPRESS STANSTED Wood Green FOREST Pinner Harrow & Finchley Central Colindale Fairlop Wealdstone Alexandra Bruce South Queensbury HARINGEY Woodford Park Turnpike Lane Grove Tottenham Blackhorse REDBRIDGE NORTHERN East Finchley North Harrow HARROW Hale Road Wood GERARDS CROSS BARNET VICTORIA Street Harold Wood Kenton Seven Barkingside Kingsbury Hendon Central Sisters RUISLIP West Harrow Highgate Harringay Central Eastcote Harrow on the Hill Green Lanes St James Snaresbrook Walthamstow Fryent Crouch Hill Street Gants Ruislip Northwick Country South -

The European Fallow Deer (Dama Dama Dama)

Heredity (2017) 119, 16–26 OPEN Official journal of the Genetics Society www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Strong population structure in a species manipulated by humans since the Neolithic: the European fallow deer (Dama dama dama) KH Baker1, HWI Gray1, V Ramovs1, D Mertzanidou2,ÇAkın Pekşen3,4, CC Bilgin3, N Sykes5 and AR Hoelzel1 Species that have been translocated and otherwise manipulated by humans may show patterns of population structure that reflect those interactions. At the same time, natural processes shape populations, including behavioural characteristics like dispersal potential and breeding system. In Europe, a key factor is the geography and history of climate change through the Pleistocene. During glacial maxima throughout that period, species in Europe with temperate distributions were forced south, becoming distributed among the isolated peninsulas represented by Anatolia, Italy and Iberia. Understanding modern patterns of diversity depends on understanding these historical population dynamics. Traditionally, European fallow deer (Dama dama dama) are thought to have been restricted to refugia in Anatolia and possibly Sicily and the Balkans. However, the distribution of this species was also greatly influenced by human-mediated translocations. We focus on fallow deer to better understand the relative influence of these natural and anthropogenic processes. We compared modern fallow deer putative populations across a broad geographic range using microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA loci. The results revealed highly insular populations, depauperate of genetic variation and significantly differentiated from each other. This is consistent with the expectations of drift acting on populations founded by small numbers of individuals, and reflects known founder populations in the north. -

Management and Control of Populations of Foxes, Deer, Hares, and Mink in England and Wales, and the Impact of Hunting with Dogs

A Report to the Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs Management and Control of Populations of Foxes, Deer, Hares, and Mink in England and Wales, and the Impact of Hunting with Dogs Macdonald, D.W.1, Tattersall, F.H.1, Johnson, P.J.1, Carbone, C.1, Reynolds, J. C.2, Langbein, J.3, Rushton, S. P.4 and Shirley, M.D.F.4 1Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Dept. of Zoology, South Parks Rd., Oxford, OX1 3PS; 2The Game Conservancy Trust, Fordingbridge, Hampshire, SP6 1EF; 3Wildlife Research Consultant, “Greenleas”, Chapel Cleeve, Minehead, Somerset TA24 6HY; 4Centre for Land Use and Water Resources Research, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Porter Building, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU Management and Control of the Population of Foxes, Deer, Hares and Mink, Macdonald et al: and the Impact of Hunting with Dogs Executive Summary 1. Why seek to control populations of foxes, deer, hares, and mink in England and Wales? · A number of interest groups seek to control populations of foxes, deer, hares and mink for various, and often for several, reasons, summarised in Chapter 2. These reasons should be considered in the context of: ¨ An often ambivalent attitude to the species and its control. ¨ The general lack of a simple relationship between damage and abundance. ¨ Differences between perceived and actual damage sustained. · Foxes are widely controlled because they are perceived to kill livestock (lambs, poultry and piglets), game (including hares) and other ground-nesting birds. ¨ Fox predation on livestock is usually low level, but widespread and sometimes locally significant. Evidence is strong that fox predation has a significant impact on wild game populations, but less so for other ground-nesting birds. -

20 Years in Epping Forest Seeing the Trees for the Wood

66 SCIENCE & OPINION Figure 1: Dulsmead beech soldiers. (Jeremy Dagley) 20 years in Epping Forest Seeing the trees for the wood Dr Jeremy Dagley, City of London Corporation’s Head of Conservation at Epping Forest There are more than 50,000 ancient pollards in Epping Forest. Most seems likely to be a little conservative. The of these lie within a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a number of living oaks is expected to top 10,000, despite many having died over the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and by any measure, cultural or last 30 years, and the total number of beeches ecological, they represent one of the most important populations looks likely to be closer to 20,000 than 15,000. However, defining individual beech trees in of old trees anywhere in Europe. The number is estimated from a some parts of the Forest is tricky because randomised survey carried out in the 1980s by a Manpower Services many are ‘coppards’, a variable mixture of Commission-led team, which concluded that there were around coppice stems, possible clonal growth and pollard heads. It will take some time to be sure 25,000 hornbeam, 15,000 beech and 10,000 oak pollards in total. of the final totals, but the aim is for the VTR to be a lasting record and one that ensures Biological recording The Epping Forest Veteran Tree our successors, to reverse an old proverb, It is a daunting number to consider managing, Register (VTR) can always see the trees for the wood. given the value of ancient trees and their relative rarity in Europe. -

Risk Assessment Information Page V1.2

Information about GB Non-native Species Risk Assessments The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) emphasises the need for a precautionary approach towards non-native species where there is often a lack of firm scientific evidence. It also strongly promotes the use of good quality risk assessment to help underpin this approach. The GB risk analysis mechanism has been developed to help facilitate such an approach in Great Britain. It complies with the CBD and reflects standards used by other schemes such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, European Plant Protection Organisation and European Food Safety Authority to ensure good practice. Risk assessments, along with other information, are used to help support decision making in Great Britain. They do not in themselves determine government policy. The Non-native Species Secretariat (NNSS) manages the risk analysis process on behalf of the GB Programme Board for Non-native Species. Risk assessments are carried out by independent experts from a range of organisations. As part of the risk analysis process risk assessments are: • Completed using a consistent risk assessment template to ensure that the full range of issues recognised in international standards are addressed. • Drafted by an independent expert on the species and peer reviewed by a different expert. • Approved by an independent risk analysis panel (known as the Non-native Species Risk Analysis Panel or NNRAP) only when they are satisfied the assessment is fit-for-purpose. • Approved for publication by the GB Programme Board for Non-native Species. • Placed on the GB Non-native Species Secretariat (NNSS) website for a three month period of public comment.