20 Years in Epping Forest Seeing the Trees for the Wood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

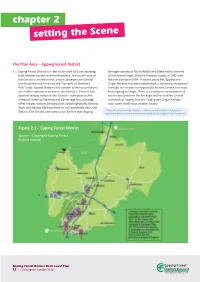

Chapter 2 Setting the Scene

chapter 2 setting the Scene The Plan Area – Epping Forest District 2.1 Epping Forest District is in the south-west of Essex abutting through stations at North Weald and Blake Hall to the end both Greater London and Hertfordshire. The south–west of of the line at Ongar. Blake Hall station closed in 1981 with the District is served by the London Underground Central the line closing in 1994. In recent years the ‘Epping and Line (both the main line and the ‘Hainault via Newbury Ongar Railway’ has been established, a nationally recognised Park’ loop). Epping Station is the eastern terminus and there heritage rail service running on this former Central Line track are 7 other stations in service in the District 1. There is one from Epping to Ongar. There is currently no operational rail national railway station in the District – at Roydon on the connection between the heritage rail line and the Central Liverpool Street to Stansted and Cambridge line, although Line track at Epping, but the ‘Epping and Ongar Railway’ other railway stations (Broxbourne, Sawbridgeworth, Harlow runs some shuttle bus services locally. Town and Harlow Mill) are close to, and accessible from, the 2 District. The Central Line used to run further than Epping, These are Theydon Bois, Debden, Loughton and Buckhurst Hill, together with the stations on the branch line at Roding Valley, Chigwell and Grange Hill Figure 2.1 – Epping Forest District Source – Copyright Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Draft Local Plan 12 | Consultation October 2016 2.2 The M25 runs east-west through the District, with a local road 2.6 By 2033, projections suggest the proportion of people aged interchange at Waltham Abbey. -

London Tube by Zuti

Stansted Airport Chesham CHILTERN Cheshunt WATFORD Epping RADLETT Stansted POTTERS BAR Theobolds Grove Amersham WALTHAM CROSS WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING FOREST Chalfont & Watford Latimer Junction Turkey Theydon ENFIELD Street Bois Watford BOREHAMWOOD London THREE RIVERS Cockfosters Enfield Town ELSTREE Copyright Visual IT Ltd OVERGROUND Southbury High Barnet Zuti and the Zuti logo are registered trademarks Chorleywood Watford Oakwood Loughton Debden High Street NEW BARNET www.zuti.co.uk Croxley BUSHEY Rickmansworth Bush Hill Park Chingford Bushey Buckhurst Hill Totteridge & Whetstone Southgate Moor Park EDGWARE Shenfield Stanmore Edmonton Carpenders Park Green Woodside Park Arnos Grove Grange Hill MAPLE CROSS Edgware Roding Chigwell Hatch End Silver Valley Northwood STANMORE JUBILEE MILL HILL EAST BARNET Street Mill Hill East West Finchley LAMBOURNE END Canons Park Bounds Green Highams Hainault Northwood Hills Headstone Lane White Hart Park Woodford Brentwood Lane NORTHWOOD Burnt Oak WALTHAM STANSTED EXPRESS STANSTED Wood Green FOREST Pinner Harrow & Finchley Central Colindale Fairlop Wealdstone Alexandra Bruce South Queensbury HARINGEY Woodford Park Turnpike Lane Grove Tottenham Blackhorse REDBRIDGE NORTHERN East Finchley North Harrow HARROW Hale Road Wood GERARDS CROSS BARNET VICTORIA Street Harold Wood Kenton Seven Barkingside Kingsbury Hendon Central Sisters RUISLIP West Harrow Highgate Harringay Central Eastcote Harrow on the Hill Green Lanes St James Snaresbrook Walthamstow Fryent Crouch Hill Street Gants Ruislip Northwick Country South -

Geology and London's Victorian Cemeteries

Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Dr. David Cook Aldersbrook Geological Society 1 Contents Part 1: Introduction Page 3 Part 2: Victorian Cemeteries Page 5 Part 3: The Rocks Page 7 A quick guide to the geology of the stones used in cemeteries Part 4: The Cemeteries Page 12 Abney Park Brompton City of London East Finchley Hampstead Highgate Islington and St. Pancras Kensal Green Nunhead Tower Hamlets West Norwood Part 5: Appendix – Page 29 Notes on other cemeteries (Ladywell and Brockley, Plumstead and Charlton) Further Information (websites, publications, friends groups) Postscript 2 Geology and London’s Victorian Cemeteries Part 1: Introduction London is a huge modern city - with congested roads, crowded shopping areas and bleak industrial estates. However, it is also a city well-served by open spaces. There are numerous small parks which provide relief retreat from city life, while areas such as Richmond Park and Riverside, Hyde Park, Hampstead Heath, Epping Forest and Wimbledon Common are real recreational treasures. Although not so obviously popular, many of our cemeteries and churchyards provide a much overlooked such amenity. Many of those established in Victorian times were designed to be used as places of recreation by the public as well as places of burial. Many are still in use and remain beautiful and interesting places for quiet walks. Some, on ceasing active use for burials, have been developed as wildlife sanctuaries and community parks. As is the case with parklands, there are some especially splendid cemeteries in the capital which stand out from the rest. I would personally recommend the City of London, Islington and St. -

RECREATION, MANAGEMENT and LANDSCAPE in EPPING FOREST:C.1800-1984

Field Studies6 (1985), 269-290 RECREATION, MANAGEMENT AND LANDSCAPE IN EPPING FOREST:c.1800-1984 R. L. LAYTON Field StudiesCouncil: Epping Forest Conseraation Centre, High Beach,Loughton, Essex ABSTRAcT The proximity of Epping Forest to London has ensured that its role as an imporr- ant centre for recreation has continued for several hundred years. It is also a Site of Special Scientific Interest, encompassinga diversity ofhabitats, many ofwhich have an ancient origin. The existence of detailed historical and contemporary records provide a unique opportunity to study the themes of recreation, management and environmental impact, including their interaction during the last two centuries. As well as considering the hisrorical trends in the Forest as a whole, the paper examines two areasin particular detail. INtnonucttoN TUB INcnpesgof leisure time in modern society has resulted in a growth of the number of people engaged in outdoor recreational pursuits. To academics, especially those in the social sciences, it has presented an exciting new field of research and investigation (Burton, 1970). Attention has focused on the themes of recreational activities, manage- ment or environmental impact. Flowever, few studies have sought to encompassall three aspects.This paper aims to investigate the relationship between visitor behaviour, land management and environmental impact, as demonstrated by Epping Forest during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The paper is divided into three sections. The first outlines the general trends in recreation, Forest management and woodland structure; the second examines the interrelationships between these three aspects; the third uses two casestudies to demonstrate these chansesin detail. Epprtlc Fonrsr-GBNERAL TRENDS The Study Area Epping Forest is an area of some 2428 hectaresof ancient woodland, plains, marsh and open water. -

Recent Releases and Dispersal of Non-Native Fishes in England and Wales, with Emphasis on Sunbleak Leucaspius Delineatus (Heckel, 1843)

Aquatic Invasions (2010) Volume 5, Issue 2: 155-161 This is an Open Access article; doi: 10.3391/ai.2010.5.2.04 Open Access © 2010 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2010 REABIC Research article Recent releases and dispersal of non-native fishes in England and Wales, with emphasis on sunbleak Leucaspius delineatus (Heckel, 1843) Grzegorz Zięba1,2, Gordon H. Copp1*,3, Gareth D. Davies4, Paul Stebbing5, Keith J. Wesley6 and J. Robert Britton3 1Salmon & Freshwater Team, Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Pakefield Road, Lowestoft, Suffolk, NR33 0HT, UK 2Permanent address: Department of Ecology & Vertebrate Zoology, University of Łódź, Banacha 12/16, 90-237 Łódź, Poland 3Centre for Conservation Ecology, School of Conservation Sciences, Bournemouth University, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB, UK 4National Fisheries Technical Team, Environm. Agency, Bromholme Lane, Brampton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, PE28 4NE, UK 5Centre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Weymouth, Dorset, DT4 8UB, UK 6Bedwell Fisheries Services, Welham Green, Hertfordshire, AL9 7LP, UK E-mail: [email protected] (GZ), [email protected] (GHC), [email protected] (GDD), [email protected] (PS), [email protected] (JRB) * Corresponding author Received: 3 November 2009 / Accepted: 20 February 2010 / Published online: 25 February 2010 Abstract The introduced range of the European cyprinid, sunbleak Leucaspius delineatus, in England was previously limited to parts of southwest England but has now expanded across Southern England. Natural dispersal mechanisms cannot explain their increased distribution and fish stocking was not a factor. Thus, the accidental movement of either their eggs or larvae via anglers’ nets was believed to be the mechanism by which these fish were accidentally moved between waters over 100 km apart. -

Everything Epping Forest 03/07/2016

Everything Epping Forest everythingeppingforest.co.uk covers the Epping Forest district in Essex and features regularly updated news - in words and pictures - has a what's on listings section to highlight local events, a Local Business Directory and a section which allows clubs and organisations to publicise their activities free of charge Home | News | Sport | Your News Views | Events - What's On Diary | Clubs - Organisations | Local Business Directory | Jobs | Food & Drink Sunday, 3 July, 2016 News Archive click here Sport Archive click here Tell us your news... Publicise your event... Promote your business... Have your say... Buy copies of photos that appear here... email: [email protected] tel: David Jackman on 07710 447868 03/07/2016 Everything Epping Forest BOBBINGWORTH: Woman 'critical' after A414 crash 10.14am - 30th May 2016 A 19-YEAR-OLD woman is in a critical condition after a single-vehicle collision on the A414 at Bobbingworth. Police were called by the ambulance service shortly before 7.50am yesterday (Sunday). A silver Vauxhall Corsa had left the road before rolling over. The driver, the 19-year-old woman, and an 18-year-old man were initially treated at the scene by ambulance paramedics. The woman was taken to Princess Alexandra Hospital, Harlow, before being transferred to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge for treatment to a serious head injury. The man did not need hospital treatment. The road was closed for one-and-a-half hours while emergency services dealt with the incident, police carried out investigations and the vehicle was recovered. Anyone who saw what happened or saw the Corsa before the crash is asked to ring the Chigwell Road Policing Unit on 101. -

Open Spaces) Bill

City of London Corporation (Open Spaces) Bill Written Answers to supplementary questions from the Senior Deputy Speaker Question 1, para 3: is the figure of £16.2m in 2016-17 a net figure (that is, does it represent the loss incurred taking into account both the income generated by and costs of running the open spaces)? Answer: 1. Yes, that is correct. In accordance with the City’s Cash Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year ended 31 March 2017, gross expenditure on Open Spaces was £21.0m and gross income was £4.8m, resulting in a net expenditure of £16.2m met from City’s Cash. Question 2, para 1: it is stated that the City “anticipate that the powers conferred by the Bill will produce income but not result in pressure on the superintendents to deploy them in order to produce income by encouraging inappropriate commercial use”. What was the business case underpinning this assertion? Answer: 1. The purpose of the provisions is to establish a clear and transparent legal framework for events that take place on the Open Spaces, and to ensure that an appropriate contribution is made to the running costs of the Open Spaces, while continuing to maintain and uphold their character and amenity. That general principle constitutes the “business case”. 2. Inappropriate commercial use will be rejected. The City Corporation’s policy in this respect is strengthened and underpinned in a number of ways. In considering any commercial activity in its Open Spaces, the City Corporation is obliged to consider its statutory obligations concerning landscape, heritage and nature protection. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES EPPING FOREST CLA/077 Page 1 Reference Description Dates STATUTORY and LEGAL PAPERS RELATING TO

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 EPPING FOREST CLA/077 Reference Description Dates STATUTORY AND LEGAL PAPERS RELATING TO PARLIAMENTARY BILLS AND ACTS CLA/077/A/01/001 Epping Forest Act 1871 1865 - 1871 Includes: report of the Parliamentary Committee (1871); petition against the Bill (1871); supporting documentation (1871); official notice of public meeting held by Epping Forest Commissioners (May 1872); report of the Open Spaces Committee (1865) inscribed 'Mr Manisty'; Report entitled "Rights of Crown in Tidal Lands and Epping Forest" (1866) 1 file Former reference: CLA/077/01/001/005 CLA/07/01/001/003 Box 1.5 Box 1.3 CLA/077/A/01/002 Epping Forest Act 1872 1872 Includes: copy of Bill; petitions against Bill; proof of the City Solicitor 1 file Former reference: CLA/077/01/001/003 Box 1.3 CLA/077/A/01/003 Epping Forest (no 1) Bill 1872 1872 Includes: copy of Bill; report; petitions against the Bill; memoranda on the amended Bill (2 copies) and reasons against a second reading 1 file Former reference: CLA/077/01/001/005 Box 1.5 CLA/077/A/01/004 Epping Forest (no 1) Bill 1872 and Metage on 1872 Grain (Port of London) Bill 1872: combined reports Includes: petitions against the Bills; minutes of evidence; reports 1 file Former reference: CLA/077/01/001/004 Box 1.4 CLA/077/A/01/005 Metage on Grain (Port of London) Act 1872 1864 - 1872 File includes: copy of Act with manuscript annotations; 2 copies of Bill with manuscript annotations; petitions; minutes of proceedings; reports and correspondence concerning rights of Metage; copy and amended -

Epping Forest Visitor Survey

EB715 EB715 EB715 This visitor report has been commissioned by the City of London Corporation as Conservators of Epping Forest, Epping Forest District Council and four other local authorities, to better understand the visitor use of Epping Forest Special Area of Conservation (SAC). The survey results will underpin the preparation of a joint strategy that will address avoidance and mitigation measures relating to increased recreation from local plan-led development. Survey work (during October and November 2017) involved counts of people passing (‘tallies’) and interviews with a random selection of people. The surveys took place at 15 locations, carefully selected to provide a good geographical spread across Epping Forest and to include a range of different types of access points, from large ‘honey-pot’ car-parks within the Forest to paths around the edge of the Forest with little opportunity to park. Survey work was similar across all survey locations, allowing direct comparison. Key findings from the survey included: • 1,065 groups of people were counted entering at the surveyed locations, and the survey point with the most people entering or passing was, by some considerable margin, Connaught Water. • Average group size across all locations from the tallies was 2.07 people (including 0.4 children) and 0.5 dogs per group. • 462 interviews were conducted, with Connaught Water, Chingford Plain and Pillow Mounds car-parks the locations with the most interviews conducted. • Virtually all (99% of interviewees) had come for a short visit directly from home (i.e. as opposed to being on holiday or staying away from home in the area). -

Epping Forest

Cultural Learning Resources OUR ENVIRONMENT E P P I N G SHEETS FACT F O R E S T Print-friendly PDF E P P I N G F O R E S T Epping Forest is a 5,900-acre area of ancient woodland between Epping in Essex to the north, and Forest Gate to the south. It is the largest public open SHEETS FACT space in the London area. It is a former royal forest, and is managed by the City of London Corporation. CONTENTS EPPING FOREST MAP 03 A BRIEF HISTORY OF EPPING FOREST 04 WILLIAM MORRIS AND EPPING FOREST 08 CHINGFORD PLAIN 09 OUR ENVIRONMENT: EPPING FOREST 02 E P P I N G F O R E S T Copped Hall Park Warlies Waltham Park Abbey Epping Gi ord Wood The Warren Plantation Epping Thicks Ambresbury Banks Theydon Bois Jacks Big View Hill Theydon Bois Deer SHEETS FACT Sanctuary Theydon Wake Green Valley Furze Pond Ground Great Monk Wood Debden Green Epping Forest Visitor Centre Little Monk Wood Baldwins Hill High Truelove’s Loughton Beach Camp Robin Hood Roundabout Femhills Staples Hill Loughton Bury The Debden Wood Stubbles Yardley Sewardstonebury Hill The Warren Loughton Connaught Warren Water Hill Chingford Golf Course Pole Queen Elizabeth Hill Hunting Lodge North Farm Chingford Whitehall Plain Chigwell Buckhurst Hill Chingford Lord’s Bushes Knighton Wood Chigwell Roding Valley Woodford Green Highams Park Woodford E P P I N G F O R E S T A Brief History of Epping Forest Early History There has been continuous tree cover in Epping Forest for well over 3,000 years, and signs of human occupation since the Iron Age.