Open Spaces) Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. Hampstead Ridge

5. Hampstead Ridge Key plan Description The Hampstead Ridge Natural Landscape Area extends north east from Ealing towards Finsbury and West Green in Tottenham, comprising areas of North Acton, Shepherd’s Bush, Paddington, Hampstead, Camden Town and Hornsey. A series of summits at Hanger Lane (65m AOD), Willesden Green Cemetery (55m AOD) and Parliament Hill (95m AOD) build the ridge, which is bordered by the Brent River to the north and the west, and the Grand Union Canal to the south. The dominant bedrock within the Landscape Area is London Clay. The ENGLAND 100046223 2009 RESERVED ALL RIGHTS NATURAL CROWN COPYRIGHT. © OS BASE MAP key exception to this is the area around Hampstead Heath, an area 5. Hampstead Ridge 5. Hampstead Ridge Hampstead 5. of loam over sandstone which lies over an outcrop of the Bagshot Formation and the Claygate Member. The majority of the urban framework comprises Victorian terracing surrounding the conserved historic cores of Stonebridge, Willesden, Bowes Park and Camden which date from Saxon times and are recorded in the Domesday Book (1086). There is extensive industrial and modern residential development (most notably at Park Royal) along the main rail and road infrastructure. The principal open spaces extend across the summits of the ridge, with large parks at Wormwood Scrubs, Regents Park and Hampstead Heath and numerous cemeteries. The open space matrix is a combination of semi-natural woodland habitats, open grassland, scrub and linear corridors along railway lines and the Grand Union Canal. 50 London’s Natural Signatures: The London Landscape Framework / January 2011 Alan Baxter Natural Signature and natural landscape features Natural Signature: Hampstead Ridge – A mosaic of ancient woodland, scrub and acid grasslands along ridgetop summits with panoramic views. -

An Artists Life in London Ebook

MY TOWN : AN ARTISTS LIFE IN LONDON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Gentleman | 288 pages | 05 Mar 2020 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9781846149757 | English | London, United Kingdom My Town : An Artists Life in London PDF Book Writing Workshops. Your order is now being processed and we have sent a confirmation email to you at. Receive regular news and offers from the London Review Bookshop. Send message Please wait It has, after all, often been made in the service of something else — a book, an amenity or, in the early days, a product Gentleman cut his teeth in advertising in the s before the ethics of it began to trouble him. John Cooper Clarke. Accessibility help Skip to navigation Skip to content Skip to footer. David Gentleman is a painter and printmaker, working in many mediums. Events Podcasts Penguin Newsletter Video. Click here to register free today! US Show more US. Isokon Penguin Donkey. Here is London as it was, and as it is today: the Thames, Hampstead Heath; the streets, canals, markets and people of his home of Camden Town; and at the heart of it all, his studio and the tools of his work. Quantity Add to basket. David Gentleman has lived in London for almost seventy years, most of it on the same street. Strictly Necessary cookies enable core functionality such as security, network management, and accessibility. Upcoming Events. Testaments Special Signed Edition. Please try again or alternatively you can contact your chosen shop on or send us an email at. Targeting cookies are used to make advertising messages more relevant to you and your interests. -

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

The Park Keeper

The Park Keeper 1 ‘Most of us remember the park keeper of the past. More often than not a man, uniformed, close to retirement age, and – in the mind’s eye at least – carrying a pointed stick for collecting litter. It is almost impossible to find such an individual ...over the last twenty years or so, these individuals have disappeared from our parks and in many circumstances their role has not been replaced.’ [Nick Burton1] CONTENTS training as key factors in any parks rebirth. Despite a consensus that the old-fashioned park keeper and his Overview 2 authoritarian ‘keep off the grass’ image were out of place A note on nomenclature 4 in the 21st century, the matter of his disappearance crept back constantly in discussions.The press have published The work of the park keeper 5 articles4, 5, 6 highlighting the need for safer public open Park keepers and gardening skills 6 spaces, and in particular for a rebirth of the park keeper’s role. The provision of park-keeping services 7 English Heritage, as the government’s advisor on the Uniforms 8 historic environment, has joined forces with other agencies Wages and status 9 to research the skills shortage in public parks.These efforts Staffing levels at London parks 10 have contributed to the government’s ‘Cleaner, Safer, Greener’ agenda,7 with its emphasis on tackling crime and The park keeper and the community 12 safety, vandalism and graffiti, litter, dog fouling and related issues, and on broader targets such as the enhancement of children’s access to culture and sport in our parks The demise of the park keeper 13 and green spaces. -

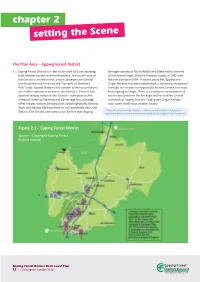

Chapter 2 Setting the Scene

chapter 2 setting the Scene The Plan Area – Epping Forest District 2.1 Epping Forest District is in the south-west of Essex abutting through stations at North Weald and Blake Hall to the end both Greater London and Hertfordshire. The south–west of of the line at Ongar. Blake Hall station closed in 1981 with the District is served by the London Underground Central the line closing in 1994. In recent years the ‘Epping and Line (both the main line and the ‘Hainault via Newbury Ongar Railway’ has been established, a nationally recognised Park’ loop). Epping Station is the eastern terminus and there heritage rail service running on this former Central Line track are 7 other stations in service in the District 1. There is one from Epping to Ongar. There is currently no operational rail national railway station in the District – at Roydon on the connection between the heritage rail line and the Central Liverpool Street to Stansted and Cambridge line, although Line track at Epping, but the ‘Epping and Ongar Railway’ other railway stations (Broxbourne, Sawbridgeworth, Harlow runs some shuttle bus services locally. Town and Harlow Mill) are close to, and accessible from, the 2 District. The Central Line used to run further than Epping, These are Theydon Bois, Debden, Loughton and Buckhurst Hill, together with the stations on the branch line at Roding Valley, Chigwell and Grange Hill Figure 2.1 – Epping Forest District Source – Copyright Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Draft Local Plan 12 | Consultation October 2016 2.2 The M25 runs east-west through the District, with a local road 2.6 By 2033, projections suggest the proportion of people aged interchange at Waltham Abbey. -

A Geotrail in Richmond Park

A Geotrail in Richmond Park 1 Richmond Park Geotrail In an urban environment it is often difficult to ‘see’ the geology beneath our feet. This is also true within our open spaces. In Richmond Park there is not much in the way of actual rocks to be seen but it is an interesting area geologically as several different rock types occur there. It is for this reason that the southwest corner has been put forward as a Locally Important Geological Site. We will take clues from the landscape to see what lies beneath. Richmond Park affords fine views to both west and east which will throw a wider perspective on the geology of London. Richmond Park is underlain by London Clay, about 51 million years old. This includes the sandier layers at the top, known as the Claygate beds. The high ground near Kingston Gate includes the Claygate beds but faulting along a line linking Pen Ponds to Ham Gate has allowed erosion on the high ground around Pembroke Lodge. Both high points are capped by the much younger Black Park Gravel, which is only about 400,000 years old, the earliest of the Thames series of terraces formed after the great Anglian glaciation. Younger Thames terrace gravels are also to be found in Richmond Park. Useful maps and guide books The Royal Parks have a printable pdf map of Richmond Park on their website: www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/richmond-park/map-of-richmond-park. Richmond Park from Medieval Pasture to Royal Park by Paul Rabbitts, 2014. Amberley Publishing. -

Press Release

BRITISH MILITARY FITNESS AT THE CAVENDISH HOTEL The Cavendish Hotel is offering its guests the most effective, unique and environmentally friendly workout possible. The hotel has teamed up with British Military Fitness (BMF) to give visitors access to complimentary fitness sessions to help them keep fit in the great outdoors. The hotel, which has a keen emphasis on reducing its impact on the environment and was awarded “Considerate Hotel of the Year 2007”, is offering its guests an alternative workout to the normal hotel gym. Residents of the hotel are invited to attend these rigorous BMF sessions with the hotel’s compliments. The BMF classes are run by serving or ex-armed forces physical training instructors with recognised fitness training qualifications. They offer motivational and challenging workouts to encourage attendees to get fit in a fun and interactive environment. The classes take place in the beautiful parks of London and are a great opportunity to take in the scenery London has to offer. Making use of the great outdoors and using no equipment, apart from what nature provides, means these workouts are the lowest carbon footprint form of exercise you can do. The classes are designed to suit guests of all fitness and the groups are divided into three levels; beginners, intermediates and advanced, so whatever the level of ability there is something for every hotel guest. Hyde Park is the local BMF venue to The Cavendish and offers sessions everyday except Tuesday at several times in the morning and the evening. Other classes take place in Clapham Common, Hampstead Heath, Richmond Park, Wimbledon Common, Battersea Park and Wandsworth Common and guests of the hotel will be able to attend any session in London. -

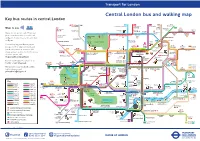

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Hampstead Heath Trails 1 Parliament Hill Highgateand the Tumulus

Hampstead Heath Trails 1 Parliament Hill Highgateand the Tumulus Ponds M i l l f ie ld L a n Trail e Dartmo 95m 17 s Park d Tumulus 3 18 Parliament Hill Fields 2 Dukes 4 Stone of Free Field 8 Parliament Hill Speech (Kite Hill) 5 98m 9 Bandstand 1 P Hampstead Ponds The trail starts here at the Heath. The ‘Saxon Ditch’ 1 the Parliament Hill Café. has been here since at least AD Follow the trail towards 986. Ancient trees and stones the chain of ponds. also mark this old manorial and parish boundary. The chain of ponds on 2 your right were dug as The summit of Parliament reservoirs around 300 5 Hill will give you a years ago. The waters of the welcome breather and River Fleet feed them. Water great views over the city. birds such as herons, great- More mystery surrounds the crested grebes and the pre- name. It may simply record the historic like cormorants can be visibility of the seat of govern- seen here. You may even catch a ment, or does it commemorate glimpse of a kingfisher. Guy Fawkes’ attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament in The Tumulus 1605? Some think that his supporters lay in waiting here to witness the deed being done. The pine-topped Tumulus 3 is something of a mys- tery. Some believe it is an ancient burial ground or the Parliament Hill resting-place of Queen Boudicca. This is a good More likely it is the site of an old spot to watch windmill or a folly, once visible migrating birds. -

London Tube by Zuti

Stansted Airport Chesham CHILTERN Cheshunt WATFORD Epping RADLETT Stansted POTTERS BAR Theobolds Grove Amersham WALTHAM CROSS WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING FOREST Chalfont & Watford Latimer Junction Turkey Theydon ENFIELD Street Bois Watford BOREHAMWOOD London THREE RIVERS Cockfosters Enfield Town ELSTREE Copyright Visual IT Ltd OVERGROUND Southbury High Barnet Zuti and the Zuti logo are registered trademarks Chorleywood Watford Oakwood Loughton Debden High Street NEW BARNET www.zuti.co.uk Croxley BUSHEY Rickmansworth Bush Hill Park Chingford Bushey Buckhurst Hill Totteridge & Whetstone Southgate Moor Park EDGWARE Shenfield Stanmore Edmonton Carpenders Park Green Woodside Park Arnos Grove Grange Hill MAPLE CROSS Edgware Roding Chigwell Hatch End Silver Valley Northwood STANMORE JUBILEE MILL HILL EAST BARNET Street Mill Hill East West Finchley LAMBOURNE END Canons Park Bounds Green Highams Hainault Northwood Hills Headstone Lane White Hart Park Woodford Brentwood Lane NORTHWOOD Burnt Oak WALTHAM STANSTED EXPRESS STANSTED Wood Green FOREST Pinner Harrow & Finchley Central Colindale Fairlop Wealdstone Alexandra Bruce South Queensbury HARINGEY Woodford Park Turnpike Lane Grove Tottenham Blackhorse REDBRIDGE NORTHERN East Finchley North Harrow HARROW Hale Road Wood GERARDS CROSS BARNET VICTORIA Street Harold Wood Kenton Seven Barkingside Kingsbury Hendon Central Sisters RUISLIP West Harrow Highgate Harringay Central Eastcote Harrow on the Hill Green Lanes St James Snaresbrook Walthamstow Fryent Crouch Hill Street Gants Ruislip Northwick Country South -

20 Years in Epping Forest Seeing the Trees for the Wood

66 SCIENCE & OPINION Figure 1: Dulsmead beech soldiers. (Jeremy Dagley) 20 years in Epping Forest Seeing the trees for the wood Dr Jeremy Dagley, City of London Corporation’s Head of Conservation at Epping Forest There are more than 50,000 ancient pollards in Epping Forest. Most seems likely to be a little conservative. The of these lie within a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a number of living oaks is expected to top 10,000, despite many having died over the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and by any measure, cultural or last 30 years, and the total number of beeches ecological, they represent one of the most important populations looks likely to be closer to 20,000 than 15,000. However, defining individual beech trees in of old trees anywhere in Europe. The number is estimated from a some parts of the Forest is tricky because randomised survey carried out in the 1980s by a Manpower Services many are ‘coppards’, a variable mixture of Commission-led team, which concluded that there were around coppice stems, possible clonal growth and pollard heads. It will take some time to be sure 25,000 hornbeam, 15,000 beech and 10,000 oak pollards in total. of the final totals, but the aim is for the VTR to be a lasting record and one that ensures Biological recording The Epping Forest Veteran Tree our successors, to reverse an old proverb, It is a daunting number to consider managing, Register (VTR) can always see the trees for the wood. given the value of ancient trees and their relative rarity in Europe.