RECREATION, MANAGEMENT and LANDSCAPE in EPPING FOREST:C.1800-1984

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION for ENGLAND PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW of EPPING FOREST Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries In

S R A M LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND Deerpark Wood T EE TR S EY DS LIN Orange Field 1 Plantation 18 BURY ROAD B CLAVERHAM Galleyhill Wood Claverhambury D A D O D LR A O IE R F Y PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF EPPING FOREST R LY U B O M H A H Bury Farm R E V A L C Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in Loughton and Waltham Abbey November 2000 GR UB B' S H NE Aimes Green ILL K LA PUC EPPING LINDSEY AND THORNWOOD Cobbinsend Farm Spratt's Hedgerow Wood COMMON WARD B UR D Y R L A D N Monkhams Hall N E E S N I B B Holyfield O C Pond Field Plantation E I EPPING UPLAND CP EPPING CP WALTHAM ABBEY NORTH EAST WARD Nursery BROADLEY COMMON, EPPING UPLAND WALTHAM ABBEY E AND NAZEING WARD N L NORTH EAST PARISH WARD A O School L N L G L A S T H R N E R E E F T ST JOHN'S PARISH WARD Government Research Establishment C Sports R The Wood B Ground O U O House R K G Y E A L D L A L M N E I E L Y E H I L L Home Farm Paris Hall R O Warlies Park A H D o r s e m Griffin's Wood Copped Hall OAD i l R l GH HI EPPING Arboretum ƒƒƒ Paternoster HEMNALL House PARISH WARD WALTHAM ABBEY EPPING HEMNALL PIC K H PATERNOSTER WARD ILL M 25 WARD z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z z EW WALTHAM ABBEY EYVI ABB AD PATERNOSTER PARISH WARD RO IRE SH UP R School School Raveners Farm iv e r L Copthall Green e e C L N L R a A v O H ig The Warren a O ti K D o K C A n I E T O WALTHAM ABBEY D R M MS Schools O I L O E R B Great Gregories OAD ILL R Farm M H FAR Crown Hill AD O Farm R Epping Thicks H IG H AD N RO -

Reading History in Early Modern England

READING HISTORY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND D. R. WOOLF published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Sabon 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Woolf, D. R. (Daniel R.) Reading History in early modern England / by D. R. Woolf. p. cm. (Cambridge studies in early modern British history) ISBN 0 521 78046 2 (hardback) 1. Great Britain – Historiography. 2. Great Britain – History – Tudors, 1485–1603 – Historiography. 3. Great Britain – History – Stuarts, 1603–1714 – Historiography. 4. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 16th century. 5. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 17th century. 6. Books and reading – England – History – 16th century. 7. Books and reading – England – History – 17th century. 8. History publishing – Great Britain – History. I. Title. II. Series. DA1.W665 2000 941'.007'2 – dc21 00-023593 ISBN 0 521 78046 2 hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Preface xi List of abbreviations and note on the text xv Introduction 1 1 The death of the chronicle 11 2 The contexts and purposes of history reading 79 3 The ownership of historical works 132 4 Borrowing and lending 168 5 Clio unbound and bound 203 6 Marketing history 255 7 Conclusion 318 Appendix A A bookseller’s inventory in history books, ca. -

Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report

APPENDIX 2 of SAC Mitigation Strategy update Epping Forest SAC Mitigation Report Amended Second Draft Final Report Prepared by LUC in association with Andrew McCloy and Huntley Cartwright September 2020 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 250 Waterloo Road Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management SE1 8RD Edinburgh 250 Waterloo Road Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Manchester London SE1 8RD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Project Title: Epping Forest SAC Mitigation. Draft Final Report Client: City of London Corporation Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1 April Draft JA JA JA 2019 HL 2 April Draft Final JA JA 2020 HL 3 April Second Draft Final JA, HL, DG/RT, JA 2020 AMcC 4 Sept Amended Second Draft JA, HL, DG/RT, JA JA 2020 Final AMcC Report on SAC mitigation Last saved: 29/09/2020 11:15 Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 This report 2 2 Research and Consultation 4 Documentary Research 4 Internal client interviews 8 Site assessment 10 3 Overall Proposals 21 Introduction 21 Overall principles 21 4 Site specific Proposals 31 Summary of costs 31 Proposals for High Beach 31 Proposals for Chingford Plain 42 Proposals for Leyton Flats 61 Implementation 72 5 Monitoring and Review 74 Monitoring 74 Review 74 Appendix 1 Access survey site notes 75 Appendix 2 Ecological survey site notes 83 Appendix 3 Legislation governing the protection -

Book2 English

UNITED-KINGDOM JEREMY DAGLEY BOB WARNOCK HELEN READ Managing veteran trees in historic open spaces: the Corporation of London’s perspective 32 The three Corporation of London sites described in ties have been set. There is a need to: this chapter provide a range of situations for • understand historic management practices (see Dagley in press and Read in press) ancient tree management. • identify and re-find the individual trees and monitor their state of health • prolong the life of the trees by management where deemed possible • assess risks that may be associated with ancient trees in particular locations • foster a wider appreciation of these trees and their historic landscape • create a new generation of trees of equivalent wildlife value and interest This chapter reviews the monitoring and manage- ment techniques that have evolved over the last ten years or so. INVENTORY AND SURVEY Tagging. At Ashtead 2237 Quercus robur pollards, including around 900 dead trees, were tagged and photographed between 1994 and 1996. At Burnham 555 pollards have been tagged, most between 1986 Epping Forest. and 1990. At Epping Forest 90 Carpinus betulus, 50 Pollarded beech. Fagus sylvatica and 200 Quercus robur have so far (Photograph: been tagged. Corporation of London). TAGGING SYSTEM (Fretwell & Green 1996) Management of the ancient trees Serially Nails: 7 cm long (steel nails are numbered tags: stainless steel or not used on Burnham Beeches is an old wood-pasture and heath galvanised metal aluminium - trees where a of 218 hectares on acid soils containing hundreds of rectangles 2.5 cm hammered into chainsaw may be large, ancient, open-grown Fagus sylvatica L. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

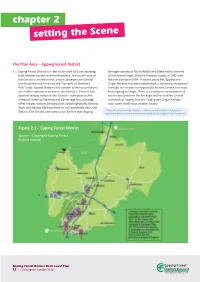

Chapter 2 Setting the Scene

chapter 2 setting the Scene The Plan Area – Epping Forest District 2.1 Epping Forest District is in the south-west of Essex abutting through stations at North Weald and Blake Hall to the end both Greater London and Hertfordshire. The south–west of of the line at Ongar. Blake Hall station closed in 1981 with the District is served by the London Underground Central the line closing in 1994. In recent years the ‘Epping and Line (both the main line and the ‘Hainault via Newbury Ongar Railway’ has been established, a nationally recognised Park’ loop). Epping Station is the eastern terminus and there heritage rail service running on this former Central Line track are 7 other stations in service in the District 1. There is one from Epping to Ongar. There is currently no operational rail national railway station in the District – at Roydon on the connection between the heritage rail line and the Central Liverpool Street to Stansted and Cambridge line, although Line track at Epping, but the ‘Epping and Ongar Railway’ other railway stations (Broxbourne, Sawbridgeworth, Harlow runs some shuttle bus services locally. Town and Harlow Mill) are close to, and accessible from, the 2 District. The Central Line used to run further than Epping, These are Theydon Bois, Debden, Loughton and Buckhurst Hill, together with the stations on the branch line at Roding Valley, Chigwell and Grange Hill Figure 2.1 – Epping Forest District Source – Copyright Epping Forest District Council Epping Forest District Draft Local Plan 12 | Consultation October 2016 2.2 The M25 runs east-west through the District, with a local road 2.6 By 2033, projections suggest the proportion of people aged interchange at Waltham Abbey. -

Public Register of Licensed Mobile Park Home Sites in the District

PUBLIC REGISTER OF LICENSED MOBILE PARK HOME SITES IN THE DISTRICT Licence Number: LN000000132 Issued: 10/09/2013 Site owner: Mr Wood Name of Site: Ashwood Farm Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 1 Other information: Pitch is not in use Licence Number: LN000000127 Issued: 05/11/2012 Site owner: Mr J & Mrs S Wenman Name of Site: Abridge Park Homes, Abridge Mobile Home Park, London Road, Abridge, Romford, Essex Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 65 Licence Number: LN000000128 Issued: 05/11/2012 Site owner: Sines Park Homes Name of Site: Breach Barns Mobile Homes, Breach Barns Mobile Home Park, Galley Hill, Waltham Abbey, Essex Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 250 Licence Number: LN000000130 Issued: 14/11/2012 Site owner: Mrs Marie Zabell Name of Site: Ludgate House Mobile Home Park, Hornbeam Lane, High Beach, Sewardstone, London, E4 7QT Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 20 Licence Number: LN000000126 Issued: 14/11/2012 Site owner: Mrs Marie Zabell Name of Site: The Owl Caravan Park, The Owl Park Home Site Lippitts Hill, High Beach, Loughton Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 20 Licence Number: LN000000125 Issued: 14/11/2012 Site owner: Mrs Marie Zabell Name of Site: The Elms Mobile Home Park, Lippitts Hill, High Beach, Loughton Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 39 Licence Number: LN000002644 Issued: 23/02/2017 Site owner: Dr Claire Zabell Name of Site: The Elms Mobile Home Park, Lippitts Hill, High Beach, Loughton Type: Residential Number of Mobile Homes: 16 Licence Number: LN000000820 Issued: -

The Employment Structure in Epping Forest District

The employment structure in Epping Forest District John Papadachi, Prosperica Ltd John Papadachi, Prosperica Ltd Table of Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................... 4 1. Employment in Epping Forest District ..................................................................... 5 1.1 ’Mobile’ ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Dominated by small businesses ...................................................................................... 5 1.3 The high skill-high reward relationship ............................................................................ 6 1.4 ’Traditional’ ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Are these characteristics connected? .............................................................................. 6 2. The district’s employment by sector........................................................................ 7 2.1 Sectoral employment in detail ........................................................................... 9 2.2 Knowledge-based sectors ............................................................................... 11 3. Enterprise ............................................................................................................. 14 3.1 How Epping Forest District performs compared with other areas ................... 14 -

Highway Verge Management

HIGHWAY VERGE MANAGEMEN T Planning and Development Note Date 23rd January 2019 Version Number 2 Highway Verge Management Review Date 30th March 2024 Author Geoff Sinclair/Richard Edmonds Highway Verge Management PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT NOTE INTRODUCTION Planning and Development Notes (PDN) aim to review and collate the City Corporation’s (CoL) property management issues for key activities, alongside other management considerations, to give an overview of current practice and outline longer term plans. The information gathered in each report will be used by the CoL to prioritise work and spending, in order to ensure firstly that the COL’s legal obligations are met, and secondly that resources are used in an efficient manner. The PDNs have been developed based on the current resource allocation to each activity. An important part of each PDN is the identification of any potential enhancement projects that require additional support. The information gathered in each report will be used by CoL to prioritise spending as part of the development of the 2019-29 Management Strategy and 2019-2022 Business Plan for Epping Forest. Each PDN will aim to follow the same structure, outlined below though sometimes not all sections will be relevant: Background – a brief description of the activity being covered; Existing Management Program – A summary of the nature and scale of the activity covered; Property Management Issues – a list of identified operational and health and safety risk management issues for the activity; Management Considerations -

Essex, Where It Remains to This Day, the Oldest Friends' School in the United Kingdom

The Journal of the Friends Historical Society Volume 60 Number 2 CONTENTS page 75-76 Editorial 77-96 Presidential Address: The Significance of the Tradition: Reflections on the Writing of Quaker History. John Punshon 97-106 A Seventeenth Century Friend on the Bench The Testimony of Elizabeth Walmsley Diana Morrison-Smith 107-112 The Historical Importance of Jordans Meeting House Sue Smithson and Hilary Finder 113-142 Charlotte Fell Smith, Friend, Biographer and Editor W Raymond Powell 143-151 Recent Publications 152 Biographies 153 Errata FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: 2004 John Punshon Clerk: Patricia R Sparks Membership Secretary/ Treasurer: Brian Hawkins Editor of the Journal Howard F. Gregg Annual membership Subscription due 1st January (personal, Meetings and Quaker Institutions in Great Britain and Ireland) raised in 2004 to £12 US $24 and to £20 or $40 for other institutional members. Subscriptions should be paid to Brian Hawkins, Membership Secretary, Friends Historical Society, 12 Purbeck Heights, Belle Vue Road, Swanage, Dorset BH19 2HP. Orders for single numbers and back issues should be sent to FHS c/o the Library, Friends House, 173 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ. Volume 60 Number 2 2004 (Issued 2005) THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Communications should be addressed to the Editor of the Journal c/o 6 Kenlay Close, New Earswick, York YO32 4DW, U.K. Reviews: please communicate with the Assistant Editor, David Sox, 20 The Vineyard, Richmond-upon-Thames, Surrey TW10 6AN EDITORIAL The Editor apologises to contributors and readers for the delayed appearance of this issue. Volume 60, No 2 begins with John Punshon's stimulating Presidential Address, exploring the nature of historical inquiry and historical writing, with specific emphasis on Quaker history, and some challenging insights in his text. -

Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630-1768 Harold Arthur Pinkham Jr

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1980 THE TRANSPLANTATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF THE ENGLISH SHIRE IN AMERICA: ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS, 1630-1768 HAROLD ARTHUR PINKHAM JR. University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation PINKHAM, HAROLD ARTHUR JR., "THE TRANSPLANTATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF THE ENGLISH SHIRE IN AMERICA: ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS, 1630-1768" (1980). Doctoral Dissertations. 2327. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2327 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. Whfle the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations vhich may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204

The loss of Normandy and the invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204 Article Accepted Version Moore, A. K. (2010) The loss of Normandy and the invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204. English Historical Review, 125 (516). pp. 1071-1109. ISSN 0013-8266 doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceq273 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/16623/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceq273 Publisher: Oxford University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204 This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in English Historical Review following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version [T. K. Moore, „The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204‟, English Historical Review (2010) CXXV (516): 1071-1109. doi: 10.1093/ehr/ceq273] is available online at: http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/content/CXXV/516/1071.full.pdf+html Dr. Tony K. Moore, ICMA Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6BA; [email protected] 2 Abstract The conquest of Normandy by Philip Augustus of France effectively ended the „Anglo-Norman‟ realm created in 1066, forcing cross-Channel landholders to choose between their English and their Norman estates.