Ethopower & Ethography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roundtable on Animal Labour

Roundtable on Animal Labour A N I M A L L A B O U R I N A M U L T I S P E C I E S S O C I E T Y : A S O C I A L J U S T I C E I S S U E ? ANIMAL LABOUR IN A MULTISPECIES SOCIETY: A SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSUE? May 1st is traditionally a day of remembrance for labour-related struggles. This year, we would like to take this opportunity to reflect on the work of animals and overcome the assumption that labour is a uniquely human affair. From foraging bees to police dogs to equine therapists, the contributions of animals through their labour to the life, wealth, and welfare of the multispecies society are manifold. The objective of this roundtable is to generate a meaningful discussion among the speakers to increase the visibility of the multi-sectoral implications of animal labour and encourage further research on this topic and its inclusion in the law. In particular, we aim to draw attention to the condition of domestic animals working in the human-animal society and the challenges posed by their legal, social and political status. Labour can be a genuine site of interspecies cooperation and flourishing, yet this can be a site of extreme instrumentalization and exploitation, too. We hope to highlight the convergence of human and animal interests in calling for the recognition of non-human animals as workers towards their better protection in the workplace. MAY 1ST, 2021, AT 7 PM (LONDON TIME) Five Animal Law and Animal Labour experts will be sharing their views on key issues, moderated by the Junior Fellows of the Think Tank on Animals & Biodiversity. -

Biopolitics and Becoming in Animal-Technology Assemblages Richie Nimmo University of Manchester

HoST - Journal of History of Science and Technology Vol. 13, no. 2, December 2019, pp. 118-136 10.2478/host-2019-0015 SPECIAL ISSUE ANIMALS, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY: MULTISPECIES HISTORIES OF SCIENTIFIC AND SOCIOTECHNICAL KNOWLEDGE-PRACTICES Biopolitics and Becoming in Animal-Technology Assemblages Richie Nimmo University of Manchester [email protected] Abstract: This article critically explores Foucauldian approaches to the human-animal-technology nexus central to modern industrialised agriculture, in particular those which draw upon Foucault’s conception of power as productive to posit the reconstitution of animal subjectivities in relation to changing agricultural technologies. This is situated in the context of key recent literature addressing animals and biopolitics, and worked through a historical case study of an emergent dairy technology. On this basis it is argued that such approaches contain important insights but also involve risks for the analyses of human-animal-technology relations, especially the risk of subsuming what is irreducible in animal subjectivity and agency under the shaping power of technologies conceived as disciplinary or biopolitical apparatuses. It is argued that this can be avoided by bringing biopolitical analysis into dialogue with currents from actor-network theory in order to trace the formation of biopolitical collectives as heterogeneous assemblages. Drawing upon documentary archive sources, the article explores this by working these different framings of biopolitics through a historical case study of the development of the first mechanical milking machines for use on dairy farms. Keywords: Foucault; actor-network theory; posthumanism; animal-technology co-becoming; multispecies biopolitics © 2019 Richie Nimmo. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). -

PDF of This Piece

A Conversation on the Feral Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel and Chloë Taylor Chloë: Thank you, Dinesh, for agreeing to engage in this conversation on the feral for Feral Feminisms. I wondered if you could start by telling us a bit about the work you have done to date in the area of Critical Animal Studies. Do you see any of this work relating to the theme of the feral? Dinesh: Thanks so much Chloë for this opportunity to chat about my work. I have been working on questions relating to animals for about 15 years. Much of my early work was focused on biopolitics, sovereignty, and exception, framed through Michel Foucault and Giorgio Agamben. I have published a monograph, The War against Animals (Wadiwel 2015), which blends this early work with newer research on domination, violence, and power, with a particular interest in Foucault’s 1975-76 lectures on biopolitics, and the understanding of politics as war pursued by other means (Foucault 2004). As I discuss in The War against Animals, Foucault’s perspective is useful for understanding human domination of animals and resonates with conceptualizations of violence and domination found in other social movements, such as the radical feminist critique of sexual violence as constituting a “war against women.” At present, I am writing a second monograph on animals under capitalism and, as part of this project, rethinking Karl Marx in relation to animals. In some ways, all of these different phases in my thinking on animals have something to say on questions of the feral. Firstly, biopolitics and exception are very useful ways to understand animals who have been constructed as feral. -

Animal-Based Food and Environmental Justice

SEI Longform Series_ February 2020 Longform Series Sydney Environment Institute Swinging the Pendulum Towards the Politics of Production: Animal-Based Food and Environmental Justice ---- Dr Dinesh Wadiwel Sydney Environment Institute 1 Sydney Environment Institute 1 Image by Carlos Neto, via Shutterstock. ID: 1517215121 Shutterstock. via Neto, Carlos by Image SEI Longform Series_ Presented at the annual Iain McCalman Lecture on February 6 2020 by Dr Dinesh Wadiwel, Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Sydney. The Iain McCalman Lecture celebrates SEI co-founder and former co-director Iain McCalman’s generous and compassionate spirit, and his dedication to fostering and pioneering multidisciplinary environmental research. The lectures aim to highlight the work of early to mid-career researchers working across disciplinary boundaries to impact both scholarship and public discourse. The research, events and operations of the Sydney Environment Institute take place at the University of Sydney, on the Gadigal lands of the Eora Nation. We pay our deepest respects to Indigenous elders, caretakers and custodians past, present and emerging, here in Eora and beyond. sydney.edu.au/sei Sydney Environment Institute 2 Dr Wadiwel explores the impact of animal agriculture on climate, planetary health and justice, and the issues with focussing on individualised responsibility, rather than structural and institutional reform. His talk seeks to swing the pendulum from the politics of consumption towards the politics of production by seeking to understand the global “metabolism” of the historically unprecedented expansion of animal-based foods under capitalism. The industrialisation of production within the context of capitalist economies has led to the mass production of animal foods as a source of profit, producing deep environmental impacts, and simultaneously exposing trillions of animals annually to the violence of intensified farming and fishing. -

Human-Animal Studies Newsletter May, 2018

Having trouble viewing this email? Click here Hi, just a reminder that you're receiving this email because you have expressed an interest in Animals and Society Institute. Don't forget to add [email protected] to your address book so we'll be sure to land in your inbox! You may unsubscribe if you no longer wish to receive our emails. Share this newsletter over social media or via email Human-Animal Studies Newsletter May, 2018 Dear Colleague, Welcome to the current issue of the Animals & Society Institute's Human- Animal Studies e-newsletter. I hope that this issue has information that is of use to you. Please let me know what you'd like to see! For future editions of this newsletter, please send submissions to [email protected]. ASI News Have you been watching our newest project, the Defining HAS Video series? We have released 10 videos so far, by scholars Peter Singer, Ken Shapiro, Corey Lee Wrenn, Lisa Kemmerer, Anthony Podberscek, Constance Russell, Maneesha Deckha, Agustin Fuentes, and David Favre, and have a bunch more waiting to come out. Take a look at the current ones, and some of the upcoming videos, here! The Animals & Society Institute (ASI) and Wesleyan Animal Studies (WAS) invite applications for the sixth annual Undergraduate Prize Competition for Undergraduate Students Pursuing Research in Human-Animal Studies. ASI and WAS will award a prize to an outstanding, original theoretical or empirical scholarly work that advances the field of human-animal studies. Papers can come from any undergraduate discipline in the humanities, social sciences or natural sciences, and must be between 4,000-7,000 words long, including abstract and references. -

Animal Studies Journal 2019 8 (2): Cover Page, Table of Contents, Editorial and Contributor Biographies

Animal Studies Journal Volume 8 Number 2 Article 1 2019 Animal Studies Journal 2019 8 (2): Cover Page, Table of Contents, Editorial and Contributor Biographies Melissa Boyde University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Art and Design Commons, Art Practice Commons, Australian Studies Commons, Communication Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Education Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Legal Studies Commons, Linguistics Commons, Philosophy Commons, Political Science Commons, Public Health Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boyde, Melissa, Animal Studies Journal 2019 8 (2): Cover Page, Table of Contents, Editorial and Contributor Biographies, Animal Studies Journal, 8(2), 2019, i-vii. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol8/iss2/1 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Animal Studies Journal 2019 8 (2): Cover Page, Table of Contents, Editorial and Contributor Biographies Abstract Animal Studies Journal 2019 8 (1): Cover Page, Table of Contents, Editorial and Notes on Contributors. This journal article is available in Animal Studies Journal: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol8/iss2/1 Animal Studies Journal Volume 8 , Number 2 201 9 Animal Studies Journal is a fully refereed journal, published twice- yearly, devoted to multidisciplinary scholarship and creative work in the field of Animal Studies. -

Should We Eat Our Research Subjects? Advocacy and Animal Studies

Animal Studies Journal Volume 7 Number 1 Article 9 2018 Should We Eat Our Research Subjects? Advocacy and Animal Studies Yvette M. Watt University of Tasmania, [email protected] Siobhan O'Sullivan University of New South Wales, [email protected] Fiona Probyn-Rapsey University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Art and Design Commons, Australian Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Philosophy Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Watt, Yvette M.; O'Sullivan, Siobhan; and Probyn-Rapsey, Fiona, Should We Eat Our Research Subjects? Advocacy and Animal Studies, Animal Studies Journal, 7(1), 2018, 180-205. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol7/iss1/9 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Should We Eat Our Research Subjects? Advocacy and Animal Studies Abstract This paper examines data from a survey of Animal Studies scholars undertaken by the authors in 2015. While the survey was broad ranging, this paper focuses on three interconnected elements; the respondents’ opinions on what role they think the field should play in regard to animal advocacy, their personal commitment to animal advocacy, and how their attitudes toward advocacy in the field differ depending on their dietary habits. While the vast majority of respondents believe that the field should demonstrate a commitment to animal wellbeing, our findings suggest that espondents’r level of commitment to animal advocacy is informed by whether they choose to eat animal products or not. -

Fish and Pain: the Politics of Doubt

Wadiwel, Dinesh Joseph (2016) Fish and pain: The politics of doubt. Animal Sentience 3(31) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1054 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Animal Sentience 2016.038: Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Fish and pain: The politics of doubt Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Dinesh Wadiwel Department of Sociology and Social Policy University of Sydney Abstract: The commentaries on Key’s (2016) target article make it clear that there is a great deal of doubt about Key’s thesis that fish do not feel pain. The political question therefore is about how we should respond to doubt. If the thesis of Key and others (that fish do not feel pain) is wrong, then the negative impact for fish in terms of suffering caused by human utilisation would be extreme. In the face of this doubt, the very least we can do is to adopt basic welfare precautions to mitigate the potential impact if fish do suffer, with attention to the means used to capture, handle and slaughter them. Dinesh Wadiwel [email protected] is lecturer in human rights and socio-legal studies at University of Sydney. His research interests include sovereignty and the nature of rights, violence, race and critical animal studies. His current book project explores the relationship between animals and capitalism, building on his monograph, The War against Animals. -

Three Fragments from a Biopolitical History of Animals: Questions of Body, Soul, and the Body Politic in Homer, Plato, and Aristotle Dinesh Wadiwel1

Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume VI, Issue 1, 2008 Three Fragments from a Biopolitical History of Animals: Questions of Body, Soul, and the Body Politic in Homer, Plato, and Aristotle Dinesh Wadiwel1 The civil political sphere – that space where human public politics occurs, where ‗the political is declared,‘ often through government, representation, measured participation and the ballot - has inherent limitations that frustrate the project of ending violence towards animals. Animals are ―by nature‖ always, at best, secondary entities, not due the political agency that is naturally bestowed upon humans. In this way a perceived fundamental differentiation undermines any claim for equivalent political agency between human and non human, and assures that animals, even if granted consideration, will always be owed a lesser degree of responsibility. These limitations very clearly underpin animal welfare approaches, which seek to minimise animal suffering without necessarily changing the frameworks of violence and power that perpetuate this suffering. For example, the notion that slaughter houses are tolerable once perceived pain is eliminated. Animal rights approaches often fare better in this regard by seeking to demonstrate the existence of unjustifiable speciesism in order to guarantee equal protections. One of their principle arguments is that the life that is held by both non human and human animals alike has an intrinsic value. Yet rights approaches themselves face constraints that reproduce the same fundamental differentiation – the gap – between human and non human. For instance, in the ―life boat case,‖ Tom Reagan stops short of agreeing that the death of an animal would constitute the same harm as the death of a human (2004: 324). -

A Sustainable Campus: the Sydney Declaration on Interspecies Sustainability

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309206066 A Sustainable Campus: The Sydney Declaration on Interspecies Sustainability Article · June 2016 CITATION READS 1 29 7 authors, including: Nik Taylor Fiona Probyn-Rapsey Flinders University University of Wollongong 82 PUBLICATIONS 629 CITATIONS 15 PUBLICATIONS 24 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Tess Lea University of Sydney 50 PUBLICATIONS 480 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Animals and Sociology View project Rescuing Me, Rescuing You: Companion Animals and Domestic Violence View project All content following this page was uploaded by Nik Taylor on 20 February 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Animal Studies Journal Volume 5 | Number 1 Article 8 6-2016 A Sustainable Campus: The yS dney Declaration on Interspecies Sustainability Fiona Probyn-Rapsey [email protected] Sue Donaldson Independent Scholar, Canada George Ioannides Independent Scholar, Australia Tess Lea University of Sydney Kate Marsh Northside Nutrition & Dietetics, Australia See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/asj Part of the Art and Design Commons, Australian Studies Commons, Creative Writing Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Philosophy Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Probyn-Rapsey, Fiona; Donaldson, Sue; Ioannides, George; Lea, Tess; Marsh, Kate; Neimanis, Astrida; Potts, Annie; Taylor, Nik; Twine, Richard; Wadiwel, Dinesh; and White, Stuart, A Sustainable Campus: The yS dney Declaration on Interspecies Sustainability, Animal Studies Journal, 5(1), 2016, 110-151. -

Sue Donaldson

Sue Donaldson Independent Researcher, Author, and Animal Advocate (Kingston, Canada) Research Associate, Department of Philosophy, Queen’s University (since 2016) Co-founder of Animals in Philosophy, Politics, Law and Ethics (APPLE) at Queen’s Email: [email protected] Mail: Department of Philosophy, Watson Hall, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, Canada, K7L 3N6 Academic Publications BOOK Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011. Co- authored with Will Kymlicka. 329 pp. Paperback edition, 2013. • Awarded the 2013 Biennial Book Prize, Canadian Philosophical Association. • Topic of symposia in Historical Social Research Vol. 40/4 (2015), pp. 47-69; Journal of Political Philosophy, Vol 23/3 (2015) pp. 282-344; Law, Ethics and Philosophy, Vol. 1 (2013) pp. 113-160; Journal of Animal Ethics, Vol. 3/2 (2013), pp. 188-219; Dialogue: Canadian Philosophical Review, Vol. 52/4 (2013), pp. 725-86; and Les Cahiers Antispécistes, numéro 37 (2015). • Topic of joint meeting of Canadian Philosophical Association and Canadian Political Science Association, June 2013; meeting of the German Political Science Association, March 2014; and Institute for Value Studies workshop at the University of Winchester, June 2016. • Translated into German as Zoopolis: Eine politische Theorie der Tierrechte (Suhrkamp, Berlin, 2013), 608 pp. • Translated into Turkish as Zoopolis: Hayvan Haklarinin Siyasal Kurami (KU Press, Istanbul, 2016), 358 pp. • Translated into French as Zoopolis: une théorie politique des droits des animaux (Alma Editeur, Paris, 2016) 408 pp. • Translated into Polish (Oficyna 21, Warsaw), forthcoming • Translated into Japanese (Shogakusha, Tokyo, 2016), 406 pp. • Translated into Spanish (Editorial Ad-Hoc, Buenos Aires), forthcoming • Chapter 2 excerpted as “Universal Basic Rights for Animals” in the Animal Ethics Reader 3rd edition, eds.: Susan J Armstrong and Richard G. -

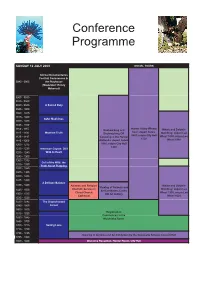

Conference Programme

Conference Programme SUNDAY 12 JULY 2009 SOCIAL TOURS Animal Documentaries Festival Commences in 0845 - 0900 the Playhouse (Moderator: Randy Malamud) 0900 - 0915 0915 - 0930 0930 - 0945 A Sacred Duty 0945 - 1000 1000 - 1015 1015 - 1030 Safer Medicines 1030 - 1045 1045 - 1100 1100-1115 Hunter Valley Winery Bushwalking and Whale and Dolphin Tour: depart hotels 1115 - 1130 Meat the Truth Birdwatching OR Watching: depart Lee 0845, return City Hall 1130 - 1145 Canoeing in the Hunter Wharf 1000, return Lee 1530 1145 - 1200 Wetlands: depart hotels Wharf 1300 1200 - 1215 0900, return City Hall 1430 1215 - 1230 American Coyote: Still 1230 - 1245 Wild At Heart 1245 - 1300 1300 - 1315 Cull of the Wild: the 1315 - 1330 Truth About Trapping 1330 - 1345 1345 - 1400 1400 - 1415 1415 - 1430 A Delicate Balance 1430 - 1445 Animals and Religion Whale and Dolphin Viewing of Animals and Interfaith Service in Watching: depart Lee 1445 - 1500 Art Exhibition, Cooks Christ Church Wharf 1330, return Lee 1500 - 1515 Hill Art Gallery Cathedral Wharf 1630 1515 - 1530 1530 - 1545 The Disenchanted 1545 - 1600 Forest 1600 - 1615 Registration 1615 - 1630 Commences in the 1630 - 1645 Mulubinba Room 1645 - 1700 1700 - 1715 Saving Luna 1715 - 1730 1730 - 1745 Viewing of Animals and Art Exhibition by the Newcastle School, Concert Hall 1745 - 1800 1800 - 1930 Welcome Reception, Hunter Room, City Hall MONDAY 13 JULY 2009 Banquet Room 0800 - 0900 Registration Concert Hall 0900 - 0905 Introductions: Rod Bennison and Jill Bough, Minding Animals Conference Co-convenors, Animals