Animation and Contemporary Art Little Nemo’S Progress - 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Teachers Guide

Teachers Guide Exhibit partially funded by: and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. TEACHERS GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 3 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW 4 CORRELATION TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS 9 EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS CHARTS 11 EXHIBIT EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES 13 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS 15 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES • BUILD YOUR OWN ZOETROPE 26 • PLAN OF ACTION 33 • SEEING SPOTS 36 • FOOLING THE BRAIN 43 ACTIVE LEARNING LOG • WITH ANSWERS 51 • WITHOUT ANSWERS 55 GLOSSARY 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 This guide was developed at OMSI in conjunction with Animation, an OMSI exhibit. 2006 Oregon Museum of Science and Industry Animation was developed by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in collaboration with Cartoon Network and partially funded by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. Animation Teachers Guide 2 © OMSI 2006 HOW TO USE THIS TEACHER’S GUIDE The Teacher’s Guide to Animation has been written for teachers bringing students to see the Animation exhibit. These materials have been developed as a resource for the educator to use in the classroom before and after the museum visit, and to enhance the visit itself. There is background information, several classroom activities, and the Active Learning Log – an open-ended worksheet students can fill out while exploring the exhibit. Animation web site: The exhibit website, www.omsi.edu/visit/featured/animationsite/index.cfm, features the Animation Teacher’s Guide, online activities, and additional resources. Animation Teachers Guide 3 © OMSI 2006 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW Animation is a 6,000 square-foot, highly interactive traveling exhibition that brings together art, math, science and technology by exploring the exciting world of animation. -

Animation 1 Animation

Animation 1 Animation The bouncing ball animation (below) consists of these six frames. This animation moves at 10 frames per second. Animation is the rapid display of a sequence of static images and/or objects to create an illusion of movement. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video program, although there are other methods. This type of presentation is usually accomplished with a camera and a projector or a computer viewing screen which can rapidly cycle through images in a sequence. Animation can be made with either hand rendered art, computer generated imagery, or three-dimensional objects, e.g., puppets or clay figures, or a combination of techniques. The position of each object in any particular image relates to the position of that object in the previous and following images so that the objects each appear to fluidly move independently of one another. The viewing device displays these images in rapid succession, usually 24, 25, or 30 frames per second. Etymology From Latin animātiō, "the act of bringing to life"; from animō ("to animate" or "give life to") and -ātiō ("the act of").[citation needed] History Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion drawing can be found in paleolithic cave paintings, where animals are depicted with multiple legs in superimposed positions, clearly attempting Five images sequence from a vase found in Iran to convey the perception of motion. A 5,000 year old earthen bowl found in Iran in Shahr-i Sokhta has five images of a goat painted along the sides. -

Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly McGill B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art & Art History 2018 i This thesis entitled: Hidden Mickey: Animation's Exclusion from Art History written by Molly McGill has been approved for the Department of Art and Art History Date (Dr. Brianne Cohen) (Dr. Kirk Ambrose) (Dr. Denice Walker) The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the Department of Art History at the University of Colorado at Boulder for their continued support during the production of this master's thesis. I am truly grateful to be a part of a department that is open to non-traditional art historical exploration and appreciate everyone who offered up their support. A special thank you to my advisor Dr. Brianne Cohen for all her guidance and assistance with the production of this thesis. Your supervision has been indispensable, and I will be forever grateful for the way you jumped onto this project and showed your support. Further, I would like to thank Dr. Kirk Ambrose and Dr. Denice Walker for their presence on my committee and their valuable input. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Catherine Cartwright and Jean Goldstein for listening to all my stress and acting as my second moms while I am so far away from my own family. -

The Animation Industry: Technological Changes, Production Challenges, and Global Shifts

THE ANIMATION INDUSTRY: TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGES, PRODUCTION CHALLENGES, AND GLOBAL SHIFTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hyejin Yoon, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Edward J. Malecki, Adviser Professor Nancy Ettlinger Adviser Graduate Program in Geography Professor Darla K. Munroe ABSTRACT Animated films have grown in popularity as expanding markets (such as TV and video) and new technologies (notably computer graphics imagery) have broadened both the production and consumption of cartoons. As a consequence, more animated films are produced and watched in more places, as new “worlds of production” have emerged. The animation production system, specialized and distinct from film production, relies on different technologies and labor skills. Therefore, its globalization has taken place differently from live-action film production, although both are structured to a large degree by the global production networks (GPNs) of the media conglomerates. This research examines the structure and evolution of the animation industry at the global scale. In order to investigate these, 4,242 animation studios from the Animation Industry Database are used. The spatial patterns of animation production can be summarized as, 1) dispersion of the animation industry, 2) concentration in world cities, such as Los Angeles and New York, 3) emergence of specialized animation cities, such as Annecy and Angoulême in France, and 4) significant concentrations of animation studios in some Asian countries, such as India, South Korea and the Philippines. In order to understand global production networks (GPNs), networks of studios in 20 cities are analyzed. -

Animation: a True Art Elyse Warnecke College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 14 Article 39 Spring 2016 Animation: A True Art Elyse Warnecke College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Warnecke, Elyse (2016) "Animation: A True Art," ESSAI: Vol. 14 , Article 39. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol14/iss1/39 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Warnecke: Animation: A True Art Animation: A True Art by Elyse Warnecke (English 1102) hen you were a kid, do you recall what you did every day after school? Many people recall watching cartoons the first thing after arriving home. You might have enjoyed shows like WSpongeBob, Jimmy Neutron, Dexter’s Laboratory, and The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy, to name a few. Behind all of these shows are extensive crews that work together to bring characters to life and make the shows enjoyable. They all feature characters facing struggles, interacting with others, following a specific plot line, all through a series of illustrations. Animation has evolved vastly along with technology, branching out to three-dimensional images created using computer programs. As there are numerous roles involved in the process of animating motion pictures, it is impossible for all the jobs to fit under one “umbrella.” However, the same general skills and attitudes are required for each job--teamwork, time management, creativity, and an open mind to new ideas. -

Introduction to Computer Animation and Its

INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTER ANIMATION AND ITS POSSIBLE EDUCATIONAL APPLICATIONS Sajid Musa a, Rushan Ziatdinov b*, Carol Griffiths c a,bDepartment of Computer and Instructional Technologies, Fatih University, 34500 Buyukcekmece, Istanbul, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] cDepartment of Foreign Language Education, Fatih University, 34500 Buyukcekmece, Istanbul, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Animation, which is basically a form of pictorial presentation, has become the most prominent feature of technology-based learning environments. It refers to simulated motion pictures showing movement of drawn objects. Recently, educational computer animation has turned out to be one of the most elegant tools for presenting multimedia materials for learners, and its significance in helping to understand and remember information has greatly increased since the advent of powerful graphics-oriented computers. In this book chapter we introduce and discuss the history of computer animation, its well- known fundamental principles and some educational applications. It is however still debatable if truly educational computer animations help in learning, as the research on whether animation aids learners’ understanding of dynamic phenomena has come up with positive, negative and neutral results. We have tried to provide as much detailed information on computer animation as we could, and we hope that this book chapter will be useful for students who study computer science, computer-assisted education or some other courses connected with contemporary education, as well as researchers who conduct their research in the field of computer animation. Keywords: Animation, computer animation, computer-assisted education, educational learning. I. Introduction For the past two decades, the most prominent feature of the technology-based learning environment has become animation (Dunbar, 1993). -

AM Tyrus Wong Film Interviewees

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMastersPBS American Masters: Tyrus Premieres nationwide Friday, September 8 at 9/8c on PBS (check local listings) in honor of the 75th anniversary of Bambi Film Interviewees Lisa See , Author and Historian She is the author of “On Gold Mountain,” which includes a chapter on Tyrus Wong. Her grandfather also owned an art gallery which exhibited Wong’s work and Dragon’s Den, the restaurant where Wong worked and painted murals and menus. She is co-curator of the exhibition, “Tyrus Wong: A Retrospective.” Ellen Harrington , Curator, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences She curated the exhibition “The Art of the Motion Picture Illustrator” at the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, which featured Tyrus Wong and two other well-known production illustrators/art directors: Bill Majors and Harold Michelson. Sonia Mak , Art Curator She curated a group show “Round the Clock: Chinese American Artists Working in Los Angeles,” which included Tyrus Wong, as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time exhibition in 2012. John Canemaker , Animation Director and Historian He wrote the book Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney Inspirational Sketch Artists , which profiled Tyrus Wong and others. Gordon T. McClelland , Author and Art Historian He is the author of numerous books on California watercolor painting, several of which include Tyrus Wong, such as California Watercolors 1850-1970 and The California Style: California Watercolor Artists, 1925-1955 . -

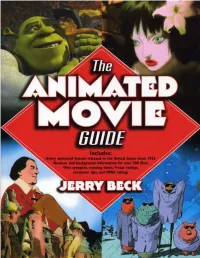

The Animated Movie Guide

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

71St 2006Summer.Pdf

SEVENTY-FIRST STREET SUMMER 2006 G VOLUME 13 G NO. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Art of the Animator . 2 SEVENTY-FIRST STREET Oscar-winning alumnus John Canemaker ’74, an internationally recognized animator, historian, professor, and author, has put his MMC degree to good use. Find out how this former actor stumbled upon MMC and embarked on his journey to scholarship and stardom. VOLUME 13 G NUMBER 3 71SUMMER 2006 Staff Updates. 5 MMC celebrates two newly appointed administrators, Maureen Grant, senior vice president, and Michael Cappeto, vice president for enrollment management Editor: Alana Klein Design: Connelly Design and student affairs. 71st Street is published twice a Recent Major Gifts to the College. 7 year by the Office of Institutional Advancement at Marymount Meet the McDougalls. 8 Manhattan College. The title Find out why Robert and Joan McDougall ’86 became so committed to MMC. recognizes the many alumni and faculty who have come to refer Trustees Report . 10 affectionately to the college MMC welcomes two new trustees and elects its first alumna as chair of the Board. by its Upper East Side address. Campus Notes. 13 Marymount Manhattan College 221 East 71st Street Read about MMC’s Commencement 2006, Spring Dance Performance, New York, NY 10021 Rudin Lecture, Strawberry Festival, and more. (212) 517-0450 Alumni Focus: Recent Events and Happenings . 16 Read about Reunion, the Washington D.C. and Florida alumni events, The views and opinions expressed the Alumni Association Induction Dinner, and more. by those in this magazine are independent and do not Class Notes. 19 necessarily represent those of Marymount Manhattan College.