2-D Or Not 2-D?: How the Iris Closed on Hand-Drawn Feature Animation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pegboard ANIMATION GUILD and AFFILIATED ELECTRONIC and GRAPHIC ARTS Los Angeles, California, April 2015 Vol

Pegboard ANIMATION GUILD AND AFFILIATED ELECTRONIC AND GRAPHIC ARTS Los Angeles, California, April 2015 Vol. 44, No. 04 CHANGES TO THE ANIMATION GUILD CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS A proposal for changes to The Animation Guild’s Constitution and By-Laws has been submitted to the Executive Board. The changes incorporate a new ascension procedure to the presidency should the sitting President no longer be able to serve, a clarifi cation and explanation of a By-Election process has been added to Article Seven, Section Nine, clarifi cation of the rules pertaining to what Guild materials the Business Representative may take from the offi ce, and some overall housekeeping-type corrections that include fi xing spelling errors, removing gender assignments where applicable and correcting syntax to better clarify specifi c articles. Per Article Fifteen, the Executive Board reviewed the proposed changes and recommended these changes be brought to the membership for review and a vote. A vote to approve the adjustments to the Constitution and By-Laws will be taken at the General Membership Meeting on the evening of May 26. President Thomas will call for a review of the proposals and a discussion on the matter before the vote is taken. All active members in good standing with the local will be called on to vote. Should two-thirds of the active members in good standing present at the meeting vote in favor of the changes, the changes will be approved by the membership and then submitted to IATSE President Loeb for review and approval. Once approved by President Loeb, the new Constitution will be printed and sent to all active members of the Guild. -

The Disney Strike of 1941: from the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, Ljohnson [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2008 The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective Lisa Johnson Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Labor Relations Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Lisa, "The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators' Perspective" (2008). Honors Projects Overview. 17. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/17 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Lisa Johnson To The Department of History Approved: Project Advisor Date Chair, Department Honors Committee Date Department Chair Date The Disney Strike of 1941: From the Animators’ Perspective By Lisa Johnson An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of History The School of the Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2008 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 I. The Strike Page 5 II. The Unheard Struggles for Control: Intellectual Property Rights, Screen Credit, Workplace Environment, and Differing Standards of Excellence Page 17 III. The Historiography Page 42 Afterword Page 56 Bibliography Page 62 2 Introduction On May 28 th , 1941, seventeen artists were escorted out of the Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California. -

(TMIIIP) Paid Projects Through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020

Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program (TMIIIP) Paid Projects through August 31, 2020 Report Created 9/29/2020 Company Project Classification Grant Amount In-State Spending Date Paid Texas Jobs Electronic Arts Inc. SWTOR 24 Video Game $ 212,241.78 $ 2,122,417.76 8/19/2020 26 Tasmanian Devil LLC Tasmanian Devil Feature Film $ 19,507.74 $ 260,103.23 8/18/2020 61 Tool of North America LLC Dick's Sporting Goods - DecembeCommercial $ 25,660.00 $ 342,133.35 8/11/2020 53 Powerhouse Animation Studios, In Seis Manos (S01) Television $ 155,480.72 $ 1,554,807.21 8/10/2020 45 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 7 Reality Television $ 603,570.00 $ 4,828,560.00 8/6/2020 519 FlipNMove Productions Inc. Texas Flip N Move Season 8 (13 E Reality Television $ 305,447.00 $ 2,443,576.00 8/6/2020 293 Nametag Films Dallas County Community CollegeCommercial $ 14,800.28 $ 296,005.60 8/4/2020 92 The Lost Husband, LLC The Lost Husband Feature Film $ 252,067.71 $ 2,016,541.67 8/3/2020 325 Armature Studio LLC Scramble Video Game $ 33,603.20 $ 672,063.91 8/3/2020 19 Daisy Cutter, LLC Hobby Lobby Christmas 2019 Commercial $ 10,229.82 $ 136,397.63 7/31/2020 31 TVM Productions, Inc. Queen Of The South - Season 2 Television $ 4,059,348.19 $ 18,041,547.51 5/1/2020 1353 Boss Fight Entertainment, Inc Zombie Boss Video Game $ 268,650.81 $ 2,149,206.51 4/30/2020 17 FlipNMove Productions Inc. -

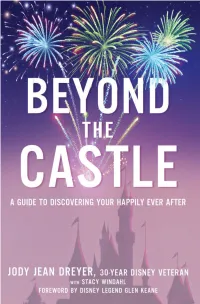

Happily Ever After

“I had a great time reading Jody’s book on her time at Disney as I have been to many of the same places and events that she attended. She went well beyond recounting her experiences though, adding many layers of texture on the how and the why of Disney storytelling. Yet Jody knows the golden rule in this business: If you knew how the trick was done, it wouldn’t be any fun anymore. At the end of the journey, she is simply in awe of the magic just as we all are, even today. Thank you, Jody, for taking us along on that journey.” – ROY P. DISNEY, grandnephew of Walt Disney “Jody may be the most organized, focused person I’ve ever met, and she has excelled in every job she’s held at the company. No one better embodies the Disney spirit.” – MICHAEL D. EISNER, former chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company “If Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse had a baby, it would be Jody Dreyer.” – DICK COOK, former chairman, Walt Disney Studios “I’m a huge believer in good storytelling. And as a fellow Disney fanatic I'm really excited to see the impact of this great read!” – KATE VOEGELE, singer/songwriter, One Tree Hill actress and recording artist on Disneymania 6 “Jody Dreyer pulls the curtain back to reveal the inner workings of one of the most fascinating and successful companies on Earth. Beyond the Castle offers incredible insight for Disney fans and business professionals alike who will relish this peek inside the magic kingdom from Jody’s unique perspective.” – DON HAHN, producer, Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King 9780310347057_UnpackingCastle_int_HC.indd 1 7/10/17 10:38 AM BEYOND THE CASTLE A GUIDE TO DISCOVERING YOUR HAPPILY EVER AFTER JODY JEAN DREYER WITH STACY WINDAHL 9780310347057_UnpackingCastle_int_HC.indd 3 7/10/17 10:38 AM ZONDERVAN Beyond the Castle Copyright © 2017 by Jody J. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

Spatial Design Principles in Digital Animation

Copyright by Laura Beth Albright 2009 ABSTRACT The visual design phase in computer-animated film production includes all decisions that affect the visual look and emotional tone of the film. Within this domain is a set of choices that must be made by the designer which influence the viewer's perception of the film’s space, defined in this paper as “spatial design.” The concept of spatial design is particularly relevant in digital animation (also known as 3D or CG animation), as its production process relies on a virtual 3D environment during the generative phase but renders 2D images as a final product. Reference for spatial design decisions is found in principles of various visual arts disciplines, and this thesis seeks to organize and apply these principles specifically to digital animation production. This paper establishes a context for this study by first analyzing several short animated films that draw attention to spatial design principles by presenting the film space non-traditionally. A literature search of graphic design and cinematography principles yields a proposed toolbox of spatial design principles. Two short animated films are produced in which the story and style objectives of each film are examined, and a custom subset of tools is selected and applied based on those objectives. Finally, the use of these principles is evaluated within the context of the films produced. The two films produced have opposite stylistic objectives, and thus show two different viewpoints of applying the toolbox. Taken ii together, the two films demonstrate application and analysis of the toolbox principles, approached from opposing sides of the same system. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

El Cine De Animación Estadounidense

El cine de animación estadounidense Jaume Duran Director de la colección: Lluís Pastor Diseño de la colección: Editorial UOC Diseño del libro y de la cubierta: Natàlia Serrano Primera edición en lengua castellana: marzo 2016 Primera edición en formato digital: marzo 2016 © Jaume Duran, del texto © Editorial UOC (Oberta UOC Publishing, SL) de esta edición, 2016 Rambla del Poblenou, 156, 08018 Barcelona http://www.editorialuoc.com Realización editorial: Oberta UOC Publishing, SL ISBN: 978-84-9116-131-8 Ninguna parte de esta publicación, incluido el diseño general y la cubierta, puede ser copiada, reproducida, almacenada o transmitida de ninguna forma, ni por ningún medio, sea éste eléctrico, químico, mecánico, óptico, grabación, fotocopia, o cualquier otro, sin la previa autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright. Autor Jaume Duran Profesor de Análisis y Crítica de Films y de Narrativa Audiovi- sual en la Universitat de Barcelona y profesor de Historia del cine de Animación en la Escuela Superior de Cine y Audiovi- suales de Cataluña. QUÉ QUIERO SABER Lectora, lector, este libro le interesará si usted quiere saber: • Cómo fueron los orígenes del cine de animación en los Estados Unidos. • Cuáles fueron los principales pioneros. • Cómo se desarrollaron los dibujos animados. • Cuáles han sido los principales estudios, autores y obras de este tipo de cine. • Qué otras propuestas de animación se han llevado a cabo en los Estados Unidos. • Qué relación ha habido entre el cine de animación y la tira cómica o los cuentos populares. Índice -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

New Directors Showcase “Congratulations” Ad Samples ©2011 Optimus

New Directors Showcase “Congratulations” Ad Samples 2011 SHOOT NEW DIRECTORS SHOWCASE congratulations otto oneatoptimus.com ©2011 Optimus. ©2011 &RQJUDWXODWLRQV +$</(<0255,6 1HZ'LUHFWRUV6KRZFDVH animation mixed media live action cg design games 9th ANNUAL NEW DIRECTORS SHOWCASE 2011 How did you get into directing? How did you get into directing? I have wanted to be a director since age 18, but felt I didn’t have enough life experience. I had a great childhood, which really shaped how I think creatively today. I grew I started taking photographs to explore the world, road trips fi nding subcultures (Angola up in a small town with only two television channels to watch. Also other than the Penitentiary inmates & characters on the Texas/Mexico borderland) and letting land- amazing mountain ranges, there weren’t a lot of exciting places to go so my imagi- scapes, like Appalachia, reveal unseen and unusual things. Two years ago I approached nation wandered quite a bit. And having a great childhood mixed with a limitless The New York Times to make a short fi lm of musicians and fans at Coachella Music Festival. imagination was really important for me because I imagined some of weirdest things The response to the fi lm was very positive and Partizan took me on as a director. I followed to make the ordinary seem out of the ordinary. So I obviously needed an outlet, but Poppy de Villeneuve up with other short fi lm and interview projects for various publications and made my fi rst Matt Fackrell we couldn’t afford a video camera, so for years my twin brother and I created strange Partizan, bicoastal/international U.K. -

An Analysis of the Character Animation in Disney's Tangled

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Carter, Chris (2013) An analysis of the character animation in Disney’s Tangled. Senses of Cinema, 2013(67), pp. 1-16. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/61227/ c Copyright 2013 Senses of Cinema Inc and the author As under the Copyright Act 1968 (Australia), no part of this journal may be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the editors except for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review. These works may be read online, downloaded and copied for the above purposes but must not be copied for any other individuals or organisations. The work itself must not be published in either print or electronic form, be edited or otherwise altered or used as a teaching resource without the express permission of the author. Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// sensesofcinema.com/ 2013/ feature-articles/ an-analysis-of-the-character-animation-in-disneys-tangled/ An Analysis of the Character Animation in Disney’s Tangled Title: Tangled (Greno and Howard 2010) Studio: Walt Disney Animation Studios Release: BLU-RAY and DVD - Australia Type: Animated Feature Film Directors: Nathan Greno, Byron Howard Animation Supervisors: Glen Keane, John Kahrs, Clay Kaytis Introduction: In the short time since PIXAR Animation created the first 3D computer animated feature film, Toy Story (John Lasseter 1995), 3D computer graphics (CG) have replaced the classical 2D realist styling of Disney Animation to become the dominant aesthetic form of mainstream animation, (P.