Animation's Exclusion from Art History by Molly Mcgill BA, University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 CSR Report

2019 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY UPDATE Table of Contents 3 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN 21 CONTENT & PRODUCTS 4 OUR BUSINESS 26 SOCIAL IMPACT 5 OUR APPROACH AND GOVERNANCE 32 LOOKING AHEAD 7 ENVIRONMENT 33 DATA AND PERFORMANCE FY19 Highlights and Recognition ........ 34 12 WORKFORCE FY19 Performance on Targets .............. 35 FY19 Data Table ..................................... 36 18 SUPPLY CHAIN LABOR STANDARDS Sustainable Development Goals ......... 39 Global Reporting Initiative Index ......... 40 Intro Our Approach and Governance Environment Workforce Supply Chain Labor Standards Content & Products Social Impact Looking Ahead Data and Performance 2 LETTER FROM OUR EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN through our Disney Aspire program, our nation’s At Disney, we also strive to have a positive impact low-carbon fuel sources, renewable electricity, and most comprehensive corporate education in our communities and on the world. This past year, natural climate solutions. I’m particularly proud of investment program, which gives employees the continuing a cause that dates back to Walt Disney the new 270-acre, 50+-megawatt solar facility that ability to pursue higher education, free of charge. himself, we took the next steps in our $100 million we brought online in Orlando. This new facility is This past year, more than half of our 94,000-plus commitment to deliver comfort and inspiration to able to generate enough clean energy to power hourly employees in the U.S. took the initial step to families with children facing serious illness using the two of the four theme parks at Walt Disney World, participate in Disney Aspire, and more than 12,000 powerful combination of our beloved characters reducing tens of thousands of tons of greenhouse enrolled in classes. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

Spatial Design Principles in Digital Animation

Copyright by Laura Beth Albright 2009 ABSTRACT The visual design phase in computer-animated film production includes all decisions that affect the visual look and emotional tone of the film. Within this domain is a set of choices that must be made by the designer which influence the viewer's perception of the film’s space, defined in this paper as “spatial design.” The concept of spatial design is particularly relevant in digital animation (also known as 3D or CG animation), as its production process relies on a virtual 3D environment during the generative phase but renders 2D images as a final product. Reference for spatial design decisions is found in principles of various visual arts disciplines, and this thesis seeks to organize and apply these principles specifically to digital animation production. This paper establishes a context for this study by first analyzing several short animated films that draw attention to spatial design principles by presenting the film space non-traditionally. A literature search of graphic design and cinematography principles yields a proposed toolbox of spatial design principles. Two short animated films are produced in which the story and style objectives of each film are examined, and a custom subset of tools is selected and applied based on those objectives. Finally, the use of these principles is evaluated within the context of the films produced. The two films produced have opposite stylistic objectives, and thus show two different viewpoints of applying the toolbox. Taken ii together, the two films demonstrate application and analysis of the toolbox principles, approached from opposing sides of the same system. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930S: Selected Excerpted Documents

Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 1 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Changes at School (Excerpted from “Changes at School,” pp. 175–76 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) Ellen Switzer, a student in Nazi Germany, recalls how her friend Ruth responded to Nazi antisemitic propaganda: Ruth was a totally dedicated Nazi. Some of us . often asked her how she could possibly have friends who were Jews or who had a Jewish background, when everything she read and distributed seemed to breathe hate against us and our ancestors. “Of course, they don’t mean you,” she would explain earnestly. “You are a good German. It’s those other Jews . who betrayed Germany that Hitler wants to remove from influence.” When Hitler actually came to power and the word went out that students of Jewish background were to be isolated, that “Aryan” Germans were no longer to associate with “non-Aryans” . Ruth actually came around and apologized to those of us to whom she was no longer able to talk. Not only did she no longer speak to the suddenly ostracized group of class - mates, she carefully noted down anybody who did, and reported them. 12 Purpose: To deepen understanding of how propaganda and conformity influence decision-making. • 186 Lesson 12: Handout 4, Document 2 German Youth in the 1930s: Selected excerpted documents Propaganda and Education (Excerpted from “Propaganda and Education,” pp. 242 –43 in Facing History and Ourselves: Holocaust and Human Behavior ) In Education for Death , American educator Gregor Ziemer described school - ing in Nazi Germany: A teacher is not spoken of as a teacher ( Lehrer ) but an Erzieher . -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

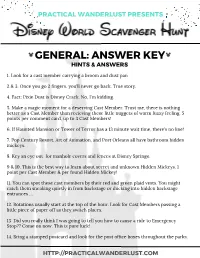

Answer Key Hints & Answers

PRACTICAL WANDERLUST PRESENTS GENERAL: ANSWER KEY HINTS & ANSWERS 1. Look for a cast member carrying a broom and dust pan 2 & 3. Once you go 2 fingers, you'll never go back. True story. 4. Fact: Pixie Dust is Disney Crack. No, I'm kidding. 5. Make a magic moment for a deserving Cast Member. Trust me, there is nothing better as a Cast Member than recieving these little nuggets of warm fuzzy feeling. 5 points per comment card, up to 3 Cast Members! 6. If Haunted Mansion or Tower of Terror has a 13 minute wait time, there's no line! 7. Pop Century Resort, Art of Animation, and Port Orleans all have bathroom hidden mickeys. 8. Key an eye out for manhole covers and fences at Disney Springs. 9 & 10. This is the best way to learn about secret and unknown Hidden Mickeys. 1 point per Cast Member & per found Hidden Mickey! 11. You can spot these cast members by their red and green plaid vests. You might catch them sneaking quietly in from backstage or ducking into hidden backstage entrances … 12. Rotations usually start at the top of the hour. Look for Cast Members passing a little piece of paper off as they switch places. 13. Did you really think I was going to tell you how to cause a ride to Emergency Stop?? Come on now. This is pure luck! 14. Bring a stamped postcard and look for the post office boxes throughout the parks. HTTP://PRACTICALWANDERLUST.COM PRACTICAL WANDERLUST PRESENTS RESORTS: ANSWER KEY HINTS & ANSWERS 1. -

Das Disney's Faces

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Humanas Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Área de concentração: História Cultural Defesa de Dissertação de Mestrado Das Disney’s faces Representações do Pato Donald sobre a Segunda Guerra (1942-4) Bárbara Marcela Reis Marques de Velasco – 07/68715 Banca Examinadora: Prof. Dr. José Walter Nunes – Orientador Profa. Dra. Maria Thereza Negrão de Mello Prof. Dr. David Rodney Lionel Pennington Profa. Dra. Márcia de Melo Martins Kuyumijan – Suplente Brasília, setembro de 2009. Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Humanas Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Área de concentração: História Cultural Defesa de Dissertação de Mestrado Das Disney’s faces Representações do Pato Donald sobre a Segunda Guerra (1942-4) Bárbara Marcela Reis Marques de Velasco – 07/68715 Brasília, setembro de 2009. Onde é que eu fui parar Aonde é esse aqui Não dá mais pra voltar Porque eu fiquei tão longe, longe (Arnaldo Antunes) Agradecimentos Ao Senhor que sabe o porquê de todas as coisas. Aos meus avós que sempre foram exemplo. Se não fosse por eles eu não estaria aqui. Aos professores membros da banca, José Walter Nunes, Maria Thereza Negrão de Mello, David Rodney Lionel Pennington, pelo resultado aqui apresentado. À força da Professora Myriam Christiano Maia Gonçalves. Motivação para seguir a diante, prosseguindo. Aos colegas Sílvia Fernandes e Ricardo Moreira. Sempre existe uma possibilidade. Vamos ver... Ao CNPq pela contribuição em parte da pesquisa. Resumo A presente pesquisa é resultado de um estudo sobre 10 produções animadas do início da década de 1940, dos estúdios Walt Disney. Protagonizadas pelo personagem Pato Donald, verifica-se nelas as mais diversas formas de representações traçadas pelos estúdios a respeito da Segunda Guerra Mundial e de alguns de seus atores: os Estados Unidos da América e seus inimigos. -

Walt Disney's Sleeping Beautywalt Disney's Sleeping Beauty Once

Walt Disney's Sleeping BeautyWalt Disney's Sleeping Beauty Once upon a time, in a kingdom far away, a beautiful princess was born ... a princess destined by a terrible curse to prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and become Sleeping Beauty. Masterful Disney animation and Tchaikovsky's celebrated musical score enrich the romantic, humorous and suspenseful story of the lovely Princess Aurora, the tree magical fairies Flora, Fauna and Merryweather, and the valiant Prince Phillip, who vows to save his beloved princess. Phillips bravery and devotion are challenged when he must confront the overwhelming forces of evil conjured up by the wicked and terrifying Maleficent. Embark on a spectacular adventure of unprecedented scale and excitement in this thrilling, timeless Disney Classic. distributed by Buena Vista film distribution co., inc. Walt Disney presents Sleeping Beauty Technirama(r) Technicolor(r) With the Talents of Mary Costa Bill Shirley Eleanor Audley Verna Felton Barbara Luddy Barbara Jo Allen Taylor Holmes Bill Thompson Production Supervisor . Ken Peterson Sound Supervisor . Robert O. Cook Film Editors . Roy M. Brewer, Jr. Donald Halliday Music Editor . Evelyn Kennedy Special Processes . Ab Iwerks Eustace Lycett (c)Copyright MCMLVIII - Walt Disney Productions - All Rights Reserved Music Adaptation George Bruns Adapted from Tchaikovsky's "Sleeping Beauty Ballet" Songs 1 George Bruns Erdman Penner Tom Adair Sammy Fain Winston Hibler Jack Lawrence Ted Sears Choral Arrangements John Karig Story Adaptation Erdman Penner From the Charles Perrault version of Sleeping Beauty Additional Story Joe Kinaldi Winston Hibler Bill Peet Ted Sears Ralph Wright Milt Banta Production Design Don Da Gradi Ken Anderson McLaren Stewart Tom Codrick Don Griffith Erni Nordli Basil Davidovich Victor Haboush Joe Hale Homer Jonas Jack Huber Kay Aragon Color Styling Eyvind Earle Background Frank Armitage Thelma Witmer Al Dempster Walt Peregoy Bill Layne Ralph Hulett Dick Anthony Fil Mottola Richard H. -

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: a Study of the Walt Disney Company’S Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11

Upholding the Disney Utopia Through American Tragedy: A Study of The Walt Disney Company's Responses to Pearl Harbor and 9/11 Lindsay Goddard Senior Thesis presented to the faculty of the American Studies Department at the University of California, Davis March 2021 Abstract Since its founding in October 1923, The Walt Disney Company has en- dured as an influential preserver of fantasy, traditional American values, and folklore. As a company created to entertain the masses, its films often provide a sense of escapism as well as feelings of nostalgia. The company preserves these sentiments by \Disneyfying" danger in its media to shield viewers from harsh realities. Disneyfication is also utilized in the company's responses to cultural shocks and tragedies as it must carefully navigate maintaining its family-friendly reputation, utopian ideals, and financial interests. This paper addresses The Walt Disney Company's responses to two attacks on US soil: the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the attacks on September 11, 200l and examines the similarities and differences between the two. By utilizing interviews from Disney employees, animated film shorts, historical accounts, insignia, government documents, and newspaper articles, this paper analyzes the continuity of Disney's methods of dealing with tragedy by controlling the narrative through Disneyfication, employing patriotic rhetoric, and reiterat- ing the original values that form Disney's utopian image. Disney's respon- siveness to changing social and political climates and use of varying mediums in its reactions to harsh realities contributes to the company's enduring rep- utation and presence in American culture. 1 Introduction A young Walt Disney craftily grabbed some shoe polish and cardboard, donned his father's coat, applied black crepe hair to his chin, and went about his day to his fifth-grade class.