Animation: a True Art Elyse Warnecke College of Dupage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animation: Types

Animation: Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer generated (CGI). Commonly the effect of animation is achieved by a rapid succession of sequential images that minimally differ from each other. Apart from short films, feature films, animated gifs and other media dedicated to the display moving images, animation is also heavily used for video games, motion graphics and special effects. The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the Paleolithic period. Shadow play and the magic lantern offered popular shows with moving images as the result of manipulation by hand and/or some minor mechanics Computer animation has become popular since toy story (1995), the first feature-length animated film completely made using this technique. Types: Traditional animation (also called cel animation or hand-drawn animation) was the process used for most animated films of the 20th century. The individual frames of a traditionally animated film are photographs of drawings, first drawn on paper. To create the illusion of movement, each drawing differs slightly from the one before it. The animators' drawings are traced or photocopied onto transparent acetate sheets called cels which are filled in with paints in assigned colors or tones on the side opposite the line drawings. The completed character cels are photographed one-by-one against a painted background by rostrum camera onto motion picture film. -

Computerising 2D Animation and the Cleanup Power of Snakes

Computerising 2D Animation and the Cleanup Power of Snakes. Fionnuala Johnson Submitted for the degree of Master of Science University of Glasgow, The Department of Computing Science. January 1998 ProQuest Number: 13818622 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818622 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY U3 ^coji^ \ Abstract Traditional 2D animation remains largely a hand drawn process. Computer-assisted animation systems do exists. Unfortunately the overheads these systems incur have prevented them from being introduced into the traditional studio. One such prob lem area involves the transferral of the animator’s line drawings into the computer system. The systems, which are presently available, require the images to be over- cleaned prior to scanning. The resulting raster images are of unacceptable quality. Therefore the question this thesis examines is; given a sketchy raster image is it possible to extract a cleaned-up vector image? Current solutions fail to extract the true line from the sketch because they possess no knowledge of the problem area. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

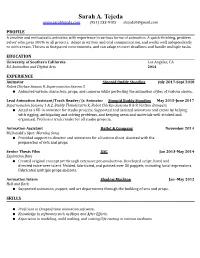

Sarah A. Tejeda (951) 233-9185 [email protected]

Sarah A. Tejeda www.sarahtejeda.com (951) 233-9185 [email protected] PROFILE A creative and enthusiastic animator, with experience in various forms of animation. A quick-thinking, problem solver who gives 100% to all projects. Adept in written and oral communication, and works well independently or with a team. Thrives in fast-paced environments, and can adapt to meet deadlines and handle multiple tasks. EDUCATION University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA BA Animation and Digital Arts 2014 EXPERIENCE Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios July 2017-Sept 2018 Robot Chicken Season 9, Supermansion Season 3 ● Animated various characters, props, and cameras while perfecting the animation styles of various shows. Lead Animation Assistant/Track Reader/ Jr. Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios May 2015-June 2017 Supermansion Seasons 1 & 2, Buddy Thunderstruck, Robot Chicken Seasons 8 & 9, Verizon Bumpers ● Acted as a fill-in animator for studio projects. Supported and assisted animators and crews by helping with rigging, anticipating and solving problems, and keeping areas and materials well-stocked and organized. Proficient track reader for all studio projects. Animation Assistant Hello! & Company November 2014 McDonald’s Spot: Morning Song ● Provided support to director and animators for a location shoot. Assisted with the preparation of sets and props. Senior Thesis Film USC Jan 2013-May 2014 Expiration Date ● Created original concept art through extensive pre-production. Developed script, hired and directed voice-over talent. Molded, fabricated, and painted over 30 puppets, including facial expressions. Fabricated multiple props and sets. Animation Intern Shadow Machine Jan -May 2012 Hell and Back ● Supported animation, puppet, and art departments through the building of sets and props. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Usage of 12 Animation Principles in the Wayang

USAGE OF 12 ANIMATION PRINCIPLES IN THE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMANCES Ming-Hsin Tsai #1, Andi Tenri Elle Hapsari *2, # Asia University, Taichung – Taiwan http://www.asia.edu.tw 1 [email protected] * Department of Digital Media Design Faculty of Creative Design 2 [email protected] Abstrak— Wayang kulit merupakan salah satu animasi tertua, animation principles will be used in this paper and further namun hingga kini belum ada penulisan lebih lanjut yang discussed in the following section. membahas tentang hubungan animasi dengan wayang kulit itu Wayang Kulit is the Indonesian shadow puppet theatre, sendiri. Dengan demikian, tulisan ini bertujuan untuk which already been acknowledge in worldwide organization memperlihatkan hubungan antara animasi yang kita kenal saat about The Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of ini dengan pertunjukan wayang kulit, menggunakan 12 prinsip dasar dari animasi sehingga terlihat persamaan penggunaan Humanity. It was a list maintained by UNESCO with pieces teknik yang ada dalam hubungannya dengan proses yang of intangible culture considered relevant by that organization. lainnya. The goal of this paper is to take a closer look at 12 principle of animation used in wayang kulit performances. The animation principles designed by Disney animators Kata kunci— Teknik animasi, 12 prinsip animasi, wayang kulit themselves, will act as guidelines to test the quality of Abstract— Wayang Kulit has been known as one of the oldest animation used in wayang kulit performances techniques, by animation; however, there is no definitive methodology that analyzing the use of the 12 traditional animation principles in supports the development process of these animation performances it. -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Teachers Guide

Teachers Guide Exhibit partially funded by: and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. TEACHERS GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 3 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW 4 CORRELATION TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS 9 EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS CHARTS 11 EXHIBIT EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES 13 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS 15 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES • BUILD YOUR OWN ZOETROPE 26 • PLAN OF ACTION 33 • SEEING SPOTS 36 • FOOLING THE BRAIN 43 ACTIVE LEARNING LOG • WITH ANSWERS 51 • WITHOUT ANSWERS 55 GLOSSARY 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 This guide was developed at OMSI in conjunction with Animation, an OMSI exhibit. 2006 Oregon Museum of Science and Industry Animation was developed by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in collaboration with Cartoon Network and partially funded by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. Animation Teachers Guide 2 © OMSI 2006 HOW TO USE THIS TEACHER’S GUIDE The Teacher’s Guide to Animation has been written for teachers bringing students to see the Animation exhibit. These materials have been developed as a resource for the educator to use in the classroom before and after the museum visit, and to enhance the visit itself. There is background information, several classroom activities, and the Active Learning Log – an open-ended worksheet students can fill out while exploring the exhibit. Animation web site: The exhibit website, www.omsi.edu/visit/featured/animationsite/index.cfm, features the Animation Teacher’s Guide, online activities, and additional resources. Animation Teachers Guide 3 © OMSI 2006 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW Animation is a 6,000 square-foot, highly interactive traveling exhibition that brings together art, math, science and technology by exploring the exciting world of animation. -

Animation 1 Animation

Animation 1 Animation The bouncing ball animation (below) consists of these six frames. This animation moves at 10 frames per second. Animation is the rapid display of a sequence of static images and/or objects to create an illusion of movement. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video program, although there are other methods. This type of presentation is usually accomplished with a camera and a projector or a computer viewing screen which can rapidly cycle through images in a sequence. Animation can be made with either hand rendered art, computer generated imagery, or three-dimensional objects, e.g., puppets or clay figures, or a combination of techniques. The position of each object in any particular image relates to the position of that object in the previous and following images so that the objects each appear to fluidly move independently of one another. The viewing device displays these images in rapid succession, usually 24, 25, or 30 frames per second. Etymology From Latin animātiō, "the act of bringing to life"; from animō ("to animate" or "give life to") and -ātiō ("the act of").[citation needed] History Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion drawing can be found in paleolithic cave paintings, where animals are depicted with multiple legs in superimposed positions, clearly attempting Five images sequence from a vase found in Iran to convey the perception of motion. A 5,000 year old earthen bowl found in Iran in Shahr-i Sokhta has five images of a goat painted along the sides. -

2D Animation Software You’Ll Ever Need

The 5 Types of Animation – A Beginner’s Guide What Is This Guide About? The purpose of this guide is to, well, guide you through the intricacies of becoming an animator. This guide is not about leaning how to animate, but only to breakdown the five different types (or genres) of animation available to you, and what you’ll need to start animating. Best software, best schools, and more. Styles covered: 1. Traditional animation 2. 2D Vector based animation 3. 3D computer animation 4. Motion graphics 5. Stop motion I hope that reading this will push you to take the first step in pursuing your dream of making animation. No more excuses. All you need to know is right here. Traditional Animator (2D, Cel, Hand Drawn) Traditional animation, sometimes referred to as cel animation, is one of the older forms of animation, in it the animator draws every frame to create the animation sequence. Just like they used to do in the old days of Disney. If you’ve ever had one of those flip-books when you were a kid, you’ll know what I mean. Sequential drawings screened quickly one after another create the illusion of movement. “There’s always room out there for the hand-drawn image. I personally like the imperfection of hand drawing as opposed to the slick look of computer animation.”Matt Groening About Traditional Animation In traditional animation, animators will draw images on a transparent piece of paper fitted on a peg using a colored pencil, one frame at the time. Animators will usually do test animations with very rough characters to see how many frames they would need to draw for the action to be properly perceived. -

MEDIA ALERT for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Stoopid Buddy Stoodios

MEDIA ALERT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Stoopid Buddy Stoodios—creative minds behind Robot Chicken TV Series—to visit The Walt Disney Family Museum in April! San Francisco, CA (March 29, 2013)—Celebrate the closing of exhibition Between Frames: The Magic Behind Stop Motion Animation with a lineup of events featuring the creators of Robot Chicken and the founders of Stoopid Buddy Stoodios! Join the team comprised of Seth Green (creator), Matthew Senreich (creator), John Harvatine IV (owner), Eric Towner (owner), and Alex Kamer (animation supervisor) for an after hours party, programs, and a workshop, exclusive to The Walt Disney Family Museum the last weekend of April. AFTER HOURS PARTY Animate Your Night: The Island of Misfit Toys Friday, April 26 | 7–10pm | Museum-wide Party with us after hours for a night full of misfit adventure! Join the creators of Robot Chicken and the founders of Stoopid Buddy Stoodios as they present behind the scenes footage and episode clips, followed by a Q&A. Enjoy eats from Adam’s Grub Truck and Me So Hungry, then have a hair-raising sip of our signature cocktail: The Evil Doctor. PANEL DISCUSSION The Making of Robot Chicken Saturday, April 27 | 2pm | The Theater Join the crew from Stoopid Buddy Stoodios, the masterminds behind the stop motion TV show Robot Chicken, for a behind-the-scenes look at the making of this modern cult favorite. WORKSHOP Learn from the Masters: Animation Mischief with Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Saturday, April 27 | 10am–1pm | Art Studio Explore the magic of stop motion animation with the Emmy and Annie Award-winning animators of Robot Chicken.